Vector Calculus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition of Riemann Integrals

The Definition and Existence of the Integral Definition of Riemann Integrals Definition (6.1) Let [a; b] be a given interval. By a partition P of [a; b] we mean a finite set of points x0; x1;:::; xn where a = x0 ≤ x1 ≤ · · · ≤ xn−1 ≤ xn = b We write ∆xi = xi − xi−1 for i = 1;::: n. The Definition and Existence of the Integral Definition of Riemann Integrals Definition (6.1) Now suppose f is a bounded real function defined on [a; b]. Corresponding to each partition P of [a; b] we put Mi = sup f (x)(xi−1 ≤ x ≤ xi ) mi = inf f (x)(xi−1 ≤ x ≤ xi ) k X U(P; f ) = Mi ∆xi i=1 k X L(P; f ) = mi ∆xi i=1 The Definition and Existence of the Integral Definition of Riemann Integrals Definition (6.1) We put Z b fdx = inf U(P; f ) a and we call this the upper Riemann integral of f . We also put Z b fdx = sup L(P; f ) a and we call this the lower Riemann integral of f . The Definition and Existence of the Integral Definition of Riemann Integrals Definition (6.1) If the upper and lower Riemann integrals are equal then we say f is Riemann-integrable on [a; b] and we write f 2 R. We denote the common value, which we call the Riemann integral of f on [a; b] as Z b Z b fdx or f (x)dx a a The Definition and Existence of the Integral Left and Right Riemann Integrals If f is bounded then there exists two numbers m and M such that m ≤ f (x) ≤ M if (a ≤ x ≤ b) Hence for every partition P we have m(b − a) ≤ L(P; f ) ≤ U(P; f ) ≤ M(b − a) and so L(P; f ) and U(P; f ) both form bounded sets (as P ranges over partitions). -

Generalizations of the Riemann Integral: an Investigation of the Henstock Integral

Generalizations of the Riemann Integral: An Investigation of the Henstock Integral Jonathan Wells May 15, 2011 Abstract The Henstock integral, a generalization of the Riemann integral that makes use of the δ-fine tagged partition, is studied. We first consider Lebesgue’s Criterion for Riemann Integrability, which states that a func- tion is Riemann integrable if and only if it is bounded and continuous almost everywhere, before investigating several theoretical shortcomings of the Riemann integral. Despite the inverse relationship between integra- tion and differentiation given by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, we find that not every derivative is Riemann integrable. We also find that the strong condition of uniform convergence must be applied to guarantee that the limit of a sequence of Riemann integrable functions remains in- tegrable. However, by slightly altering the way that tagged partitions are formed, we are able to construct a definition for the integral that allows for the integration of a much wider class of functions. We investigate sev- eral properties of this generalized Riemann integral. We also demonstrate that every derivative is Henstock integrable, and that the much looser requirements of the Monotone Convergence Theorem guarantee that the limit of a sequence of Henstock integrable functions is integrable. This paper is written without the use of Lebesgue measure theory. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Patrick Keef and Professor Russell Gordon for their advice and guidance through this project. I would also like to acknowledge Kathryn Barich and Kailey Bolles for their assistance in the editing process. Introduction As the workhorse of modern analysis, the integral is without question one of the most familiar pieces of the calculus sequence. -

Worked Examples on Using the Riemann Integral and the Fundamental of Calculus for Integration Over a Polygonal Element Sulaiman Abo Diab

Worked Examples on Using the Riemann Integral and the Fundamental of Calculus for Integration over a Polygonal Element Sulaiman Abo Diab To cite this version: Sulaiman Abo Diab. Worked Examples on Using the Riemann Integral and the Fundamental of Calculus for Integration over a Polygonal Element. 2019. hal-02306578v1 HAL Id: hal-02306578 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02306578v1 Preprint submitted on 6 Oct 2019 (v1), last revised 5 Nov 2019 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Worked Examples on Using the Riemann Integral and the Fundamental of Calculus for Integration over a Polygonal Element Sulaiman Abo Diab Faculty of Civil Engineering, Tishreen University, Lattakia, Syria [email protected] Abstracts: In this paper, the Riemann integral and the fundamental of calculus will be used to perform double integrals on polygonal domain surrounded by closed curves. In this context, the double integral with two variables over the domain is transformed into sequences of single integrals with one variable of its primitive. The sequence is arranged anti clockwise starting from the minimum value of the variable of integration. Finally, the integration over the closed curve of the domain is performed using only one variable. -

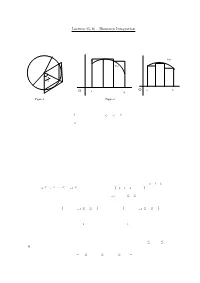

Lecture 15-16 : Riemann Integration Integration Is Concerned with the Problem of finding the Area of a Region Under a Curve

1 Lecture 15-16 : Riemann Integration Integration is concerned with the problem of ¯nding the area of a region under a curve. Let us start with a simple problem : Find the area A of the region enclosed by a circle of radius r. For an arbitrary n, consider the n equal inscribed and superscibed triangles as shown in Figure 1. f(x) f(x) π 2 n O a b O a b Figure 1 Figure 2 Since A is between the total areas of the inscribed and superscribed triangles, we have nr2sin(¼=n)cos(¼=n) · A · nr2tan(¼=n): By sandwich theorem, A = ¼r2: We will use this idea to de¯ne and evaluate the area of the region under a graph of a function. Suppose f is a non-negative function de¯ned on the interval [a; b]: We ¯rst subdivide the interval into a ¯nite number of subintervals. Then we squeeze the area of the region under the graph of f between the areas of the inscribed and superscribed rectangles constructed over the subintervals as shown in Figure 2. If the total areas of the inscribed and superscribed rectangles converge to the same limit as we make the partition of [a; b] ¯ner and ¯ner then the area of the region under the graph of f can be de¯ned as this limit and f is said to be integrable. Let us de¯ne whatever has been explained above formally. The Riemann Integral Let [a; b] be a given interval. A partition P of [a; b] is a ¯nite set of points x0; x1; x2; : : : ; xn such that a = x0 · x1 · ¢ ¢ ¢ · xn¡1 · xn = b. -

Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher. Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Please use the following citation format: Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher, Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed [Date]). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike. Also available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Note: Please use the actual date you accessed this material in your citation. For more information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms 8 MAGNETOQUASISTATIC FIELDS: SUPERPOSITION INTEGRAL AND BOUNDARY VALUE POINTS OF VIEW 8.0 INTRODUCTION MQS Fields: Superposition Integral and Boundary Value Views We now follow the study of electroquasistatics with that of magnetoquasistat ics. In terms of the flow of ideas summarized in Fig. 1.0.1, we have completed the EQS column to the left. Starting from the top of the MQS column on the right, recall from Chap. 3 that the laws of primary interest are Amp`ere’s law (with the displacement current density neglected) and the magnetic flux continuity law (Table 3.6.1). � × H = J (1) � · µoH = 0 (2) These laws have associated with them continuity conditions at interfaces. If the in terface carries a surface current density K, then the continuity condition associated with (1) is (1.4.16) n × (Ha − Hb) = K (3) and the continuity condition associated with (2) is (1.7.6). a b n · (µoH − µoH ) = 0 (4) In the absence of magnetizable materials, these laws determine the magnetic field intensity H given its source, the current density J. -

Intuitive Mathematical Discourse About the Complex Path Integral Erik Hanke

Intuitive mathematical discourse about the complex path integral Erik Hanke To cite this version: Erik Hanke. Intuitive mathematical discourse about the complex path integral. INDRUM 2020, Université de Carthage, Université de Montpellier, Sep 2020, Cyberspace (virtually from Bizerte), Tunisia. hal-03113845 HAL Id: hal-03113845 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03113845 Submitted on 18 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Intuitive mathematical discourse about the complex path integral Erik Hanke1 1University of Bremen, Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, Germany, [email protected] Interpretations of the complex path integral are presented as a result from a multi-case study on mathematicians’ intuitive understanding of basic notions in complex analysis. The first case shows difficulties of transferring the image of the integral in real analysis as an oriented area to the complex setting, and the second highlights the complex path integral as a tool in complex analysis with formal analogies to path integrals in multivariable calculus. These interpretations are characterised as a type of intuitive mathematical discourse and the examples are analysed from the point of view of substantiation of narratives within the commognitive framework. -

General Riemann Integrals and Their Computation Via Domain

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 General Riemann Integrals and Their omputC ation via Domain. Bin Lu Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Lu, Bin, "General Riemann Integrals and Their omputC ation via Domain." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7001. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7001 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, phnt bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

More Information About Line and Contour Integrals

More information about line and contour integrals. Real line integrals. Let P (x, y)andQ(x, y) be continuous real valued functions on the plane and let γ be a smooth directed curve. We wish to define the line integral Z P (x, y) dx + Q(x, y) dy. γ This can be done in several ways. One of which is to partition the curve γ by a very large number of points, define Riemann sums for the partition, and then take a limit as the “mesh” of the partition gets finer and finer. However an argument like the one we did in class for complex line integrals shows that if c(t)=(x(t),y(t)) with a ≤ t ≤ b is a smooth parameterization of γ then Z Z b P (x, y) dx + Q(x, y) dy = P (x(t),y(t))x0(t)+Q(x(t),y(t)) dt. γ a R This reduces computing γ P (x, y) dx + Q(x, y) dy to first finding a parameterization of γ and then computing a standard Riemann integral such as we have all seen in calculus. Here is an example. Let γ be the upper half of the circle |z| =1 transversed counter clockwise. Then compute Z (1) xy2 dx − (x + y + x3y) dy. γ This half circle is parameterized by x(t)=cos(t),y(t)=sin(t) with 0 ≤ t ≤ π. Now the calculation proceeds just as if we were doing a change of variables. That is dx = − sin(t) dt, dy = cos(t) dt 1 2 Using these formulas in (1) gives Z xy2 dx − (x + y + x3y) dy γ Z π = cos(t)sin2(t)(− sin(t)) dt − (cos(t)+sin(t)+cos3(t)sin(t)) cos(t) dt Z0 π = cos(t)sin2(t)(− sin(t)) − (cos(t)+sin(t)+cos3(t)sin(t)) cos(t) dt 0 With a little work1 this can be shown to have the value −(2/5+π/2). -

Fractional Integrals and Derivatives • Yuri Luchko Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: “True” Versus “False”

Fractional Integrals and Derivatives • Yuri Luchko Yuri • Fractional Integrals and Derivatives “True” versus “False” Edited by Yuri Luchko Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Mathematics www.mdpi.com/journal/mathematics Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: “True” versus “False” Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: “True” versus “False” Editor Yuri Luchko MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Yuri Luchko Beuth Technical University of Applied Sciences Berlin Germany Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Mathematics (ISSN 2227-7390) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/mathematics/special issues/Fractional Integrals Derivatives). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-0365-0494-0 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-0365-0494-0 (PDF) © 2021 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Preface to ”Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: “True” versus “False”” ............. ix Yuri Luchko and Masahiro Yamamoto The General Fractional Derivative and Related Fractional Differential Equations Reprinted from: Mathematics 2020, 8, 2115, doi:10.3390/math8122115 ............... -

On a New Generalized Integral Operator and Certain Operating Properties

axioms Article On a New Generalized Integral Operator and Certain Operating Properties Paulo M. Guzman 1,2,†, Luciano M. Lugo 1,†, Juan E. Nápoles Valdés 1,† and Miguel Vivas-Cortez 3,*,† 1 FaCENA, UNNE, Av. Libertad 5450, Corrientes 3400, Argentina; [email protected] (P.M.G.); [email protected] (L.M.L.); [email protected] (J.E.N.V.) 2 Facultad de Ingeniería, UNNE, Resistencia, Chaco 3500, Argentina 3 Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Escuela de Ciencias Físicas y Matemática, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito 170143, Ecuador * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 20 April 2020; Accepted: 22 May 2020; Published: 20 June 2020 Abstract: In this paper, we present a general definition of a generalized integral operator which contains as particular cases, many of the well-known, fractional and integer order integrals. Keywords: integral operator; fractional calculus 1. Preliminars Integral Calculus is a mathematical area with so many ramifications and applications, that the sole intention of enumerating them makes the task practically impossible. Suffice it to say that the simple procedure of calculating the area of an elementary figure is a simple case of this topic. If we refer only to the case of integral inequalities present in the literature, there are different types of these, which involve certain properties of the functions involved, from generalizations of the known Mean Value Theorem of classical Integral Calculus, to varied inequalities in norm. Let (U, ∑ U, u) and (V, ∑ V, m) be s-fìnite measure spaces, and let (W, ∑ W, l) be the product of these spaces, thus W = UxV and l = u x m. -

The Generalized Riemann Integral Robert M

AMS / MAA THE CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS VOL AMS / MAA THE CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS VOL 20 20 The Generalized Riemann Integral Robert M. McLeod The Generalized Riemann Integral The Generalized The Generalized Riemann Integral is addressed to persons who already have an acquaintance with integrals they wish to extend and to the teachers of generations of students to come. The organization of the Riemann Integral work will make it possible for the rst group to extract the principal results without struggling through technical details which they may nd formidable or extraneous to their purposes. The technical level starts low at the opening of each chapter. Thus, readers may follow Robert M. McLeod each chapter as far as they wish and then skip to the beginning of the next. To readers who do wish to see all the details of the arguments, they are given. The generalized Riemann integral can be used to bring the full power of the integral within the reach of many who, up to now, haven't gotten a glimpse of such results as monotone and dominated conver- gence theorems. As its name hints, the generalized Riemann integral is de ned in terms of Riemann sums. The path from the de nition to theorems exhibiting the full power of the integral is direct and short. AMS / MAA PRESS 4-color Process 290 pages spine: 9/16" finish size: 5.5" X 8.5" 50 lb stock 10.1090/car/020 THE GENERALIZED RIEMANN INTEGRAL By ROBERT M. McLEOD THE CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Committee on Publications E. -

Steady-State Electric and Magnetic Fields

Steady State Electric and Magnetic Fields 4 Steady-State Electric and Magnetic Fields A knowledge of electric and magnetic field distributions is required to determine the orbits of charged particles in beams. In this chapter, methods are reviewed for the calculation of fields produced by static charge and current distributions on external conductors. Static field calculations appear extensively in accelerator theory. Applications include electric fields in beam extractors and electrostatic accelerators, magnetic fields in bending magnets and spectrometers, and focusing forces of most lenses used for beam transport. Slowly varying fields can be approximated by static field calculations. A criterion for the static approximation is that the time for light to cross a characteristic dimension of the system in question is short compared to the time scale for field variations. This is equivalent to the condition that connected conducting surfaces in the system are at the same potential. Inductive accelerators (such as the betatron) appear to violate this rule, since the accelerating fields (which may rise over many milliseconds) depend on time-varying magnetic flux. The contradiction is removed by noting that the velocity of light may be reduced by a factor of 100 in the inductive media used in these accelerators. Inductive accelerators are treated in Chapters 10 and 11. The study of rapidly varying vacuum electromagnetic fields in geometries appropriate to particle acceleration is deferred to Chapters 14 and 15. The static form of the Maxwell equations in regions without charges or currents is reviewed in Section 4.1. In this case, the electrostatic potential is determined by a second-order differential equation, the Laplace equation.