Relationship Between Text Display Method and College Student Short Term Knowledge Retention During Self-Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

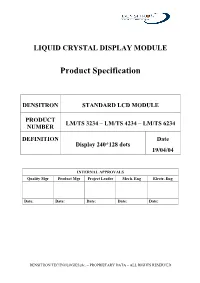

Liquid Crystal Display Module

LIQUID CRYSTAL DISPLAY MODULE Product Specification DENSITRON STANDARD LCD MODULE PRODUCT LM/TS 3234 – LM/TS 4234 – LM/TS 6234 NUMBER DEFINITION Date Display 240*128 dots 19/04/04 INTERNAL APPROVALS Quality Mgr Product Mgr Project Leader Mech. Eng Electr. Eng Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: DENSITRON TECHNOLOGIES plc. – PROPRIETARY DATA – ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PART NUMBER DESCRIPTION FOR AVAILABLE OPTIONS....................................................................................4 2 MAIN FEATURES..................................................................................................................................................................5 3 MECHANICAL SPECIFICATION ......................................................................................................................................6 3.1 MECHANICAL CHARACTERISTICS..........................................................................................................................6 3.2 MECHANICAL DRAWING...........................................................................................................................................7 4 ELECTRICAL SPECIFICATION........................................................................................................................................8 4.1 ABSOLUTE MAXIMUM RATINGS.............................................................................................................................8 4.2 ELECTRICAL CHARACTERISTICS............................................................................................................................8 -

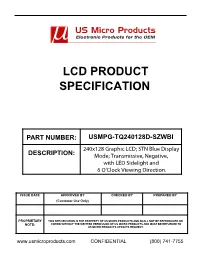

Lcd Product Specification

LCD PRODUCT SPECIFICATION PART NUMBER: USMPG-TQ240128D-SZWBI 240x128 Graphic LCD; STN Blue Display DESCRIPTION: Mode; Transmissive, Negative, with LED Sidelight and 6 O'Clock Viewing Direction. ISSUE DATE APPROVED BY CHECKED BY PREPARED BY (Customer Use Only) PROPRIETARY THIS SPECIFICATION IS THE PROPERTY OF US MICRO PRODUCTS AND SHALL NOT BE REPRODUCED OR NOTE: COPIED WITHOUT THE WRITTEN PERMISSION OF US MICRO PRODUCTS AND MUST BE RETURNED TO US MICRO PRODUCTS UPON ITS REQUEST. www.usmicroproducts.com CONFIDENTIAL (800) 741-7755 USMPG-TQ240128D-SZWBI 1.Features a) +5V power supply b) Built-in controller (RA6963L2NA) c) 240x128 dots graphic LCD module d) STN Blue mode, transmissive; neagative display e) Viewing direction: 6:00 O’clock f) 1/128 duty cycle g) (white)LED backlight 2.Outline dimension CONFIDENTIAL 3.Absolute maximum ratings Item Symbol Standard Unit Power voltage VDD-VSS 0 - 7.0 V Input voltage VIN VSS - VDD Operating temperature range VOP -20 - +70 ℃ Storage temperature range VST -30 - +80 www.usmicroproducts.com 1 (800) 741-7755 USMPG-TQ240128D-SZWBI 4.Block diagram /WR COM /RD LCD PANEL /CE 240X128 Dots C/D COM /RST DB0~DB7 RA6963 FS 13 COL COL COL VDD 8 RAM V0 VSS 2 FG VEE DC/DC LEDA LED SIDE(WHITE) 5.Interface pin description Pin External CONFIDENTIAL Symbol Function No. connection 1 VSS Signal ground for LCM (GND) 2 VDD Power supply Power supply for logic (+5V) for LCM 3 V0 Operating voltage for LCD 4 C/D MPU H: Instruction L: Data 5 /RD MPU Read enable signal 6 /WR MPU Write enable signal 7~14 DB0~DB7 MPU Data bus line 15 /CE MPU Chip enable signal 16 /RST MPU Reset signal 17 VEE Negative voltage output 18 MD2 Selection of number of columns:H-32,L-40 19 FS MPU Font selection: H=6x8 dot matrix, L=8x8 dot matrix 20 LEDA BKL power supply Power supply for BKL(+5.0V) Contrast adjust DC/DC build in VDD~V0: LCD Driving voltage VR: 10k~20k www.usmicroproducts.com 2 (800) 741-7755 USMPG-TQ240128D-SZWBI 6.Optical characteristics θ φ 1 φ1 2 θ2 12:00 9:00 3:00 6:00 STN type display module (Ta=25℃, VDD=5.0V) Item Symbol Condition Min. -

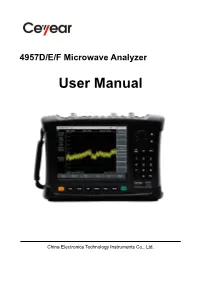

4957 User Manual

4957D/E/F Microwave Analyzer User Manual China Electronics Technology Instruments Co., Ltd. Contents Foreword Thanks very much for purchasing and using the 4957D/E/F microwave analyzer produced by China Electronics Technology Instruments Co., Ltd. The Company follows the ISO9000 standard always during production and adheres to the customer-oriented and quality-first principles. Please read carefully the manual, so as to facilitate the operation. We will spare no efforts to meet your requirements, providing you with operating devices with the higher cost performance and better after-sales services. We always adhere to the principle of“Good Quality, Satisfied Service”, providing customers with satisfactory products and services as well as work convenience and shortcut. The hotline is shown below, and we are looking forward to hear from you: Qingdao Tel: +86-0532-86896691 Website: www.ceyear.com E-mail: [email protected] Address: No. 98, Xiangjiang Road, Qingdao City, China Postal code: 266555 The manual introduces the application, performance and features, basic principles, usage, maintenance and precautions of the 4957D/E/F microwave analyzer, facilitating your quick understanding the usage and key points of the tester. To operate the product well and provide you with higher economic effectiveness, please read the manual carefully. Mistakes and omissions can hardly be avoided due to time urgency and writer’s knowledge limit. Your valuable comments and suggestions are highly welcome! We are sorry for any inconvenience caused due to our errors. The manual is the third version of the 4957D/E/F microwave analyzer Manual, with version number of C.2. The contents hereof are subject to change without notice. -

Prepared by Dr.P.Sumathi

COMPUTER GRAPHICS 18BIT53C UNIT I: Overview of Graphics System – Display Devices – CRT – Random Scan and Raster Scan Monitors – Techniques for Producing Colour Display – Beam – Penetration and Shadow – Mask Methods – DVST – Plasma – Panel Displays – Hardcopy Devices – Printers and Plotters – Display Processors – Output Primitives – DDA and Bresenham’s line drawing algorithms – Antialiasing lines – Bresenham’s Circle Algorithm – Character Generation. UNIT II: Two-dimensional Transformations – Scaling, Translation and Rotation – Matrix Representations – Composite Transformations – Reflection – Shearing – Other Transformations. Windowing and Clipping – Concepts – Cohen and Sutherland Line Clipping Algorithm – Midpoint Subdivision. UNIT III: Three dimensional Concept- Three-Dimensional object representations – polygon surfaces – polygon tables- plane equations - Three-Dimensional geometric transformations – translation – rotation – scaling – other transformations. UNIT IV: Three-Dimensional viewing – viewing pipeline - Display Techniques – Parallel Projection – Perspective Projection – Hidden-Surface and Hidden-Line removal – Back face removal – Depth Buffer Method – Scan Line Method – BSP Tree Methods – Depth-Sorting Method – Area-subdivision Method – Octree Methods – Comparison of Hidden-Surface Methods. UNIT V: Colour models and colour applications – properties of light – standard primaries and the chromaticity diagram – xyz colour model – CIE chromaticity diagram – RGB colour model – YIQ, CMY, HSV colour models, conversion between HSV and RGB models, HLS colour model, colour selection and applications. TEXT BOOK 1. Donald Hearn and Pauline Baker, “Computer Graphics”, Prentice Hall of India, 2001. Prepared by Dr.P.Sumathi 1 COMPUTER GRAPHICS Computer graphics is an art of drawing pictures on computer screens with the help of programming. It involves computations, creation, and manipulation of data. In other words, we can say that computer graphics is a rendering tool for the generation and manipulation of images. -

Se-7034-19 Htv-Ru710seriesdsht

RU710 Series Hospitality TVs 43" HG43RU710NFXZA 55" HG55RU710NFXZA 50" HG50RU710NFXZA 65" HG65RU710NFXZA Make every guest RU710 Series Hospitality TVs 4K UHD Edge-Lit LED TVs with outstanding detail and color. experience an Make sure your guest rooms remain the showcases of elegance you’ve designed them to be. The Samsung RU710 hospitality TVs look stunning before they’re even turned on, with unsurpassed one. stylish stands that look good from every angle, and a clean cable management system. Once your guests do power them on, the 4K UHD screens display content with exceptional detail and amazingly rich, vibrant color. And Samsung’s LYNK™ DRM technology protects content, while offering guests a seamless viewing experience. Install a premium experience in every room. Install the Samsung RU710 series TVs. Key Features 4K UHD with PurColor for Breathtaking Color Deliver the unmatched, luxury experience your guests expect with 3840 x 2160 4K UHD resolution. Offering four times the pixels of Full HD, the RU710 series showcases content in stunning, lifelike detail. PurColor technology concentrates on red, green, and blue color adjustment points, but unlike traditional LED, PurColor also adjusts magenta, yellow and cyan. The result is fine-tuned color of incredible nuance and realism. Easier, Faster Control with Home App and Eden UI The Home app installed on the RU710 allows you to easily incorporate a welcome message, add logos/branding, and provide other useful information such as phone extensions to various guest services. Displayed on the Eden user interface, it’s a sleek, fast, simple solution. HDR10+ Picture Technology for Incredible Depth 4K UHD delivers more pixels, and HDR10+ gets the most out of every one. -

LCD Component Data Sheet Model Number: 12864-12

PACIFIC DISPLAY DEVICES LCD Component Data Sheet Model Number: 12864-12 128 x 64 Dot STN Graphic LCD Assembly With T-6963C Graphics Controller LED / EL Panel Backlight CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Product Overview 2 1.2 Part Options and Numbering System 2 1.3 Absolute Maximum Ratings 3 1.4 Circuit Block Diagram 3 1.5 Mechanical Characteristics 3 1.6 Input Signal Function 4 1.7 LCM Power, Contrast Control and Bias 4 1.8 LCD Dimensions 5 2. ELECTRICAL / OPTICAL CHARACTERISTICS 2.1 DC Electrical Characteristics 6 2.2 AC Electrical Characteristics 7 2.3 Optical Characteristics 9 2.4 LED Backlight Characteristics 11 2.5 EL Panel Backlight Characteristics 11 3. LCD CONTROLLER CHARACTERISTICS 3.1 LCD Controller Display and Control Functions (T6963) 12 3.2 LCD Controller Command List 25 3.3 LCD Controller Character Code map 26 3.4 Application Circuits 27 4. RELIABILITY 28 5. PRECAUTIONS FOR USING LCD MODULES 29 139 Avenida Victoria – Suite 100 – San Clemente, CA – 92672 Tel: 949-361-8957 – Fax: 949-361-9158 – Web: www.pacificdisplay.com SPECIFICATIONS FOR LIQUID CRYSTAL DISPLAY MODULE MODEL NO: 12864-12 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Product Overview • 128 x 64 dot matrix LCD • STN (Super Twisted Nematic) or FSTN (Film compensated Super Twisted Nematic) Technology • T-6963 (or equivalent) Graphics Controller IC w/ 8K SRAM. • Multiplex drive : 1/64 duty, 1/9 bias • LCD Module Service Life: 100,000 hours minimum 1.2 Part Options and Numbering System 12864 -12 -SL -F -ST -ELED -GY -6 ¾ Custom Option Designator: • (-12) T6963 Graphic Controller -

Information Display • the Journal of Data Display Technology

whatever your computer says ... Volume9 Number6 November/December 1972 Information Display • The journal of Data Display Technology PANEL DISPLAYS I") I ') I.J \ll z ,-. "t V l -J SELF-SCAN Panel Display Subsystem, 256"Ch.aracter . 7 0 t M t ix Characters 0.25 Htgh. ~:?c~~;~~~e~ lor~at, !~ailable with all drive ele_ctronics including memory, character generator, and ttmmg. Whether it's a police officer. mapa. 1 ~o 1ca r requestingd. t s informa-for h·t t speclfymg coor ma e lion on a suspect, an arc I ~clding or a type setter verifying type plumbing fixtures m a ne;E~~-SCAN panel displays guarantee for a mall-order catalogf f data between the operator and the most accurate trans er o uter dis lay and demand the computer. If yo~ ne~d a ~o~tw the le:d of Kustom Electronics error-free commun l cat~~n~, oce Accessories Corporation (1) in Chanute, Kansas, Cle ~ i Ke boards (3) in (2) in Southport, .connectlcdu:;,:~~~ ~th:r SELF-SCAN panel Belleview, Washmgton, an salesman demonstrate his displa.y a why the SELF-SCAN panel us~rs. H~ve Bu.~r~u~'~lssee Circle Reader Service Ca rd No. 25 a bnefcaffse .t. oman/machine interface device d"teisprmmlay ~ISlm th e most e ec lve available today. Burroughs Corpora t1.on, Electronic Components Division, Burroughs Plainfield, New Jersey 07061 . (201) 757-3400. ~~ A Technology Publ ishing Corp. Publicat ion Volume9 Number6 November/December 1972 Information Display The journal of Data Display Technology The Sykes 2220 Cassette Tape Controller receives, stores and transmits data between termi nals and communications lines all day long. -

Final Report

Color Dot Matrix Proof of Concept A Major Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the faculty Of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute Worcester, MA In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By ________________________ Stephen Hansen Electrical and Computer Engineering ʻ12 ________________________ Brandon Rubadou Electrical and Computer Engineering ʻ12 Project Advisor: Professor Stephen Bitar Electrical and Computer Engineering Table of Contents Acknowledgements!.........................................................1 Abstract!............................................................................1 Introduction!......................................................................1 1. Background!..................................................................2 1.1 Defining Goals..................................................................................! 2 1.2 Background Research!.....................................................................3 1.2.1 Motion Sensing LED Panels!......................................................................3 1.2.2 Dot Matrices!................................................................................................4 1.2.3 Peggy!...........................................................................................................6 2. Design Details!............................................................10 2.1 Choosing the Design!.....................................................................10 2.1.1 High Resolution LED Display -

Electronic Displays Technical Report

California Energy Commission DOCKETED 12-AAER-2A TN 72475 Electronic DisplaysJAN 08 2014 Technical Report - Engineering and Cost Analysis In Support of the Codes and Standards Enhancement (CASE) Initiative For PY 2013: Title 20 Standards Development Supplemental to CASE Report submitted on July 29, 2013 Docket #12-AAER-2A January 8, 2014 Prepared for: PACIFIC GAS & ELECTRIC SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO GAS AND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA COMPANY EDISON ELECTRIC GAS COMPANY Prepared by: Clancy Donnelly, Katherine Dayem, and Brendan Trimboli, Ecova This report was prepared by the California Statewide Utility Codes and Standards Program and funded by the California utility customers under the auspices of the California Public Utilities Commission. Copyright 2014 Pacific Gas and Electric Company, Southern California Edison, Southern California Gas Company, San Diego Gas & Electric. All rights reserved, except that this document may be used, copied, and distributed without modification. Neither PG&E, SCE, SoCalGas, SDG&E, nor any of its employees makes any warranty, express of implied; or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of any data, information, method, product, policy or process disclosed in this document; or represents that its use will not infringe any privately-owned rights including, but not limited to, patents, trademarks or copyrights. Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 1 -

Head-Mounted Displays and Dynamic Text Presentation to Aid Reading in Macular Disease

HEAD-MOUNTED DISPLAYS AND DYNAMIC TEXT PRESENTATION TO AID READING IN MACULAR DISEASE Howard Farnoush Freemantle Moshtael-Oskui Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Engineering Heriot-Watt University School of Engineering & Physical Sciences January 2017 The copyright in this thesis is owned by the author. Any quotation from the thesis or use of any of the information contained in it must acknowledge this thesis as the source of the quotation or information. ABSTRACT The majority of individuals living with significant sight loss have residual vision which can be enhanced using low vision aids. Smart glasses and smartphone-based headsets, both increasing in prevalence, are proposed as a low vision aid platform. Three novel tests for measuring the visibility of displays to partially sighted users are described, along with a questionnaire for assessing subjective preference. Most individuals tested, save those with the weakest vision, were able to see and read from both a smart glasses screen and a smartphone screen mounted in a headset. The scheme for biomimetic scrolling, a text presentation strategy which translates natural eye movement into text movement, is described. It is found to enable the normally sighted to read at a rate five times that of continuous scrolling and is faster than rapid serial visual presentation for individuals with macular disease. With text presentation on the smart glasses optimised to the user, individuals with macular disease read on average 65% faster than when using their habitual optical aid. It is concluded that this aid demonstrates clear benefit over the commonly used devices and is thus recommended for further development towards widespread availability. -

Microcontroller-Based Moving Message Display Powered by Photovoltaic Energy

International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality European Association for the Development of Renewable (ICREPQ’10) Energies, Environment and Power Quality (EA4EPQ) Granada (Spain), 23rd to 25th March, 2010 Microcontroller-Based Moving Message Display Powered by Photovoltaic Energy F. H. Fahmy, S. M. Sadek, N. M. Ahamed, M. B. Zahran, and Abd El-Shafy A. Nafeh Electronics Research Institute, PV Dept., NRC Building, El-Tahrir St., Dokki, 12311-Giza, Egypt Tel./Fax+202- 33310512/33351631 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. energy (e.g. solar energy, wind, hydrogen geothermal The aim of this paper is to design a textual display ….etc.) [1]. system, based on a light emitting diode (LED) dot matrix Solar energy is a renewable energy source that is array powered by solar energy. The paper involves taking environmentally friendly, unexhausted and unlike fossil the device from an initial concept, through a design phase, fuels, solar energy is available just about everywhere on to constructing a prototype of the product. The system earth and this source of energy is free. Stand-alone consists of the display unit, which is powered from a photovoltaic (PV) systems are designed to operate, photovoltaic ( PV) module and a solar sealed lead acid independent of electric utility grid. They are excellent for battery.. The self-contained nature of the intended design remote applications where utility grid is inaccessible and will allow the display to be mounted almost anywhere it is in locations where significant connection cost makes grid needed. Therefore, the main purpose of this paper is to power prohibitively expensive. -

Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA

Adaptive Display of Virtual Content for Title Improving Usability and Safety in Mixed and Augmented Reality Author(s) Orlosky, Jason Citation Issue Date Text Version ETD URL https://doi.org/10.18910/55854 DOI 10.18910/55854 rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University Adaptive Display of Virtual Content for Improving Usability and Safety in Mixed and Augmented Reality January 2016 Jason Edward ORLOSKY Adaptive Display of Virtual Content for Improving Usability and Safety in Mixed and Augmented Reality Submitted to the Graduate School of Information Science and Technology Osaka University January 2016 Jason Edward ORLOSKY Thesis Committee Prof. Haruo Takemura (Osaka University) Prof. Takao Onoye (Osaka University) Assoc. Prof. Yuichi Itoh (Osaka University) Assoc. Prof. Kiyoshi Kiyokawa (Osaka University) I List of Publications Journals 1) Orlosky, J., Toyama, T., Kiyokawa, K., and Sonntag, D. ModulAR: Eye-controlled Vision Augmentations for Head Mounted Displays. In IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (Proc. ISMAR), Vol. 21, No. 11. pp. 1259–1268, 2015. (Section 5.3) 2) Orlosky, J., Toyama, T., Sonntag, D., and Kiyokawa, K. The Role of Focus in Advanced Visual Interfaces. In KI-Künstliche Intelligenz. pp. 1–10, 2015. (Chapter 4) 3) Orlosky, J., Shigeno, T. Kiyokawa, K. and Takemura, H. Text Input Evaluation with a Torso-mounted QWERTY Keyboard in Wearable Computing. In Transaction of the Virtual Reality Society of Japan. Vol.19, No. 2, pp. 117–120, 2014. (Section 6.3) 4) Kishishita, N., Orlosky, J., Kiyokawa, K., Mashita, T., and Takemura, H. Investigation on the Peripheral Visual Field for Information Display with Wide-view See-through HMDs.