Commercial Speech in the Professions: the Supreme Court's Unanswered Questions and Questionable Answers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Ahead: a Guide to Protecting Your Clients' Interests in the Event Of

PLANNING AHEAD: A GUIDE TO PROTECTING YOUR CLIENTS’ INTERESTS IN THE EVENT OF YOUR DISABILITY OR DEATH A Handbook and Forms 2016 Idaho State Bar PO Box 895 Boise, ID 83701 www.isb.idaho.gov (208) 334-4500 Board of Commissioners Trudy Hanson Fouser President Tim Gresback Past President Michelle R. Points Commissioner Dennis S. Voorhees Commissioner Kent A. Higgins Commissioner Executive Director Diane K. Minnich Bar Counsel Bradley G. Andrews DISCLAIMER This handbook is designed to minimize the likelihood of you or your estate being sued for legal malpractice in the event of your death, disability, impairment, or incapacity. The material presented does not establish, report, or create the standard of care for attorneys. The material is not a complete analysis of the topic, and readers should conduct their own appropriate legal research. May 2016 Dear Idaho Lawyer: This handbook was created to help you fulfill your ethical obligations to protect your clients' interests in the event of your death, disability, impairment, or incapacity. Although it is hard to think about events that could render you unable to continue practicing law, freak accidents, unexpected illness, and untimely death do occur. Following the suggestions in this handbook will help to protect your clients' interests and will help to make your practice a valuable asset to your estate. In addition, it will simplify the closure of your office - a step your family and colleagues will very much appreciate. We hope this handbook will be of assistance to you. Sincerely, Senior Lawyers Transition Task Force William F. (Bud) Yost III, Chair Hon. -

Designing a New Tier of Civil Legal Professional for Survivors of Domestic Violence

REPORT TO THE ARIZONA SUPREME COURT TASK FORCE ON DELIVERY OF LEGAL SERVICES Designing a New Tier of Civil Legal Professional for Survivors of Domestic Violence Innovation for Justice Program Innovating Legal Services Course, Spring 2019 www.law.arizona.edu/i4j This page intentionally blank. INTRODUCTION Students in the Innovating Legal Services course at the University of Arizona designed a one-year pilot program that would provide legal training to lay legal advocates at Emerge Center Against Domestic Abuse (“Emerge”). Emerge currently has seven lay legal advocates who assist domestic violence survivors (“participants”) in navigating civil legal processes. Domestic violence survivors typically navigate the civil legal system without the assistance of counsel, or with limited advice and brief service from legal aid agencies. Currently, lay legal advocates can provide legal information to survivors, but cannot offer legal advice. In this pilot program, lay legal advocates who complete a training and exam offered by the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law would be certified for a one-year period as “LLAs,” a new tier of civil legal service provider. As LLAs, they would be licensed to provide legal advice to Emerge participants in specific areas. The pilot would provide valuable information about whether a new tier of legal service can improve access to justice in the civil legal system. This report provides an overview of the pilot program, including: (1) the scope of legal services that LLAs could provide; (2) how LLAs would be trained at University of Arizona Law; (3) how the LLAs would be certified, licensed and regulated by the State Bar of Arizona; (4) how the bench, bar and public would receive education regarding the new LLA program; (5) recommendations for evaluation of the pilot; (6) expected costs of the pilot. -

Client Trust Accounting for Arizona Attorneys

Client Trust Accounting for Arizona Attorneys Publication of the State Bar of Arizona © 2014 All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer The State Bar’s Lawyer Regulation Office and Special Services Department have prepared this Client Trust Accounting Manual for Arizona Attorneys for its members. It has not been adopted or endorsed by the State Bar’s Board of Governors, and does not constitute the official position or policy of the State Bar of Arizona. It is advisory only and is not binding on the Arizona Supreme Court. The Manual contains legal information, not legal advice. While the State Bar will make every effort to update the manual as necessary, it is the responsibility of members to make sure that they are following the most current version of the Arizona Supreme Court Rules, which contain the Arizona Rules of Professional Conduct, in conjunction with this manual. Nothing contained in this Manual is intended to address any specific legal inquiry, nor is it a substitute for independent legal research to original sources or for obtaining the advice of legal counsel with respect to legal problems. The workbook may not be reproduced or copied in any manner without the express, written permission of the State Bar of Arizona. For information or a copy of this workbook, contact the State Bar of Arizona, 4201 N. 24th Street, Suite 100, Phoenix, AZ 85016-6266. Acknowledgements Selected portions of this manual were adopted, adapted, and/or reprinted from the materials originally authored by the following jurisdictions and individuals with their permission: The State Bar of California, Handbook on Client Trust Accounting for California Attorneys © 2006 (For the current online version of the California Handbook, please go to: http://www.calbar.ca.gov/calbar/pdfs/ethics/2006_CTA_Handbook.pdf) at State Bar of Arizona Trust Account Manual Section I, Pages 2-3, Section II, Pages 6-26, Section III, Pages 27-32, Section IV, Pages 33-40, Section VI, Pages 47-49, Section VII, Pages 54-56, Section VIII, Pages 59-70, and Section IX, Pages 72-83. -

Model Guideline for the Utilization of Legal Assistant

Model Guidelines For The Utilization Of Legal Assistant Services The following advisory guidelines were adopted by the Idaho State Bar membership during the 1992 resolution process. These guidelines are an attempt to identify the proper role of a legal assistant, and to define the lawyer’s supervisory role. Because the Model Guidelines are advisory only, they do not conflict with the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct. There are 10 guidelines, covering a lawyer’s supervisory and training responsibilities, the permissible scope of delegation, how legal assistants are held out to clients, the courts and the public, and guidelines for the billing of a legal assistant’s time. Preamble assistant’s education, training, and experience, and for ensuring that the legal assistant is familiar with the responsibilities of attorneys and legal assistants under the State courts, bar associations, or bar committees in at least 4 seventeen states have prepared recommendations1 for the applicable rules governing professional conduct. utilization of legal assistant services.2 While their content Under principles of agency law and rules governing the varies, their purpose appears uniform: to provide lawyers conduct of attorneys, lawyers are responsible for the actions and the work product of the non-lawyers they employ. Rule with a reliable basis for delegating responsibility for 5 performing a portion of the lawyer’s tasks to legal assistants. 5.3 of the Model Rules requires that partners and supervising The purpose of preparing model guidelines is not to contradict attorneys ensure that the conduct of non-lawyer assistants is the guidelines already adopted or to suggest that other compatible with the lawyer’s professional obligations. -

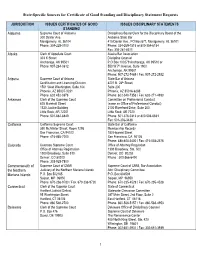

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests JURISDICTION ISSUES CERTIFICATES OF GOOD ISSUES DISCIPLINARY STATEMENTS STANDING Alabama Supreme Court of Alabama Disciplinary Board Clerk for the Disciplinary Board of the 300 Dexter Ave. Alabama State Bar Montgomery, AL 36104 415 Dexter Ave., PO Box 671, Montgomery, AL 36101 Phone: 334-229-0700 Phone: 334-269-1515 or 800-354-6154 Fax: 334-261-6311 Alaska Clerk of Appellate Court Alaska Bar Association 303 K Street Discipline Counsel Anchorage, AK 99501 P.O Box 100279 Anchorage, AK 99510 or Phone: 907-264-0612 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1900 Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-272-7469 / Fax: 907-272-2932 Arizona Supreme Court of Arizona State Bar of Arizona Certification and Licensing Division 4201 N. 24th Street, 1501 West Washington, Suite 104 Suite 200 Phoenix, AZ 85007-3231 Phoenix, AZ 85016-6288 Phone: 602 452-3378 Phone: 602-340-7353 / Fax: 602-271-4930 Arkansas Clerk of the Supreme Court Committee on Professional Conduct 625 Marshall Street (same as Office of Professional Conduct) 1320 Justice Building 2100 Riverfront Drive, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Little Rock, AR 7220 Phone: 501-682-6849 Phone: 501-376-0313 or 800-506-6631 Fax: 501-376-3438 California California Supreme Court State Bar of California 350 McAllister Street, Room 1295 Membership Records San Francisco, CA 94102 180 Howard Street Phone: 415-865-7000 San Francisco, CA 94105 Phone: 888-800-3400 / Fax: 415-538-2576 Colorado Colorado Supreme Court Office of Attorney Regulation Office of Attorney Registration 1300 Broadway, Ste. -

1 No. 19-35463 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

(1 of 41) Case: 19-35463, 11/13/2019, ID: 11498160, DktEntry: 30-1, Page 1 of 2 No. 19-35463 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ________________ DANIEL Z. CROWE, OREGON CIVIL LIBERTIES ATTORNEYS; AND LAWRENCE K. PETERSON, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. STATE BAR OF OREGON, Defendant-Appellee, _______________________________________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Oregon, Portland Division Case No. 3:18-cv-02139-JR Honorable Michael H. Simon MOTION OF STATE BAR OF ARIZONA FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF SUPPORTING APPELLEE Mary R. O’Grady Kimberly Friday OSBORN MALEDON, P.A. 2929 North Central Avenue, Suite 2100 Phoenix, Arizona 85012 (602) 640-9000 [email protected] Attorneys for State Bar of Arizona 1 (2 of 41) Case: 19-35463, 11/13/2019, ID: 11498160, DktEntry: 30-1, Page 2 of 2 The State Bar of Arizona (“Arizona”) moves for leave to file an amicus brief supporting the State Bar of Oregon in this case. The proposed brief is filed with this motion. The State Bar of Oregon consents to Arizona filing this brief. Appellants oppose the filing of this brief. Arizona has an interest in the court’s decision in this case because Arizona, like Oregon, has an integrated bar in which membership is required. The amicus brief will provide information on state bars in jurisdictions other than Oregon to provide the Court with a broader perspective on the varied systems for regulating the practice of law. Because of the potentially broad impact of the court’s decision, information on other state bars should be useful to the court. -

The End of Mandatory State Bars?

The End of Mandatory State Bars? LESLIE C. LEVIN* The country’s thirty-one mandatory state bar associations are fac- ing an existential threat following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Janus v. ACSME, 138 S. Ct. 2448 (2018). In Janus, the Court considered the constitutionality of compelling public employees to pay agency fees to a labor union. In the process, the Court effectively upended the reasoning of earlier Supreme Court precedent that enabled mandatory state bars to com- pel bar dues payments from objecting lawyers and expend dues to fund tra- ditional bar functions. Mandatory state bars—which function both as regu- lators and as traditional bar associations—are now defending themselves against claims in several states that compelled bar dues payments violate lawyers’ First Amendment rights. This Essay considers whether these com- pelled payments are likely to withstand constitutional scrutiny post-Janus. It focuses on the constitutional analysis outlined in Janus, with emphasis on the question of whether the states’ interest in lawyer regulation and improv- ing the quality of legal services can be achieved through alternative means that are significantly less restrictive of lawyers’ associational freedom than compelled bar dues payments. To answer this question, the Essay compares the activities of the country’s mandatory and voluntary state bar associa- tions along several dimensions. The comparison reveals that states with mandatory bars are unlikely to be able to demonstrate that the states’ in- terests cannot be achieved through significantly less restrictive means. While this result would be a loss for the legal profession, there could be benefits for the public. -

February-2000-Volume-13.Pdf

In politics, this is the premier address. ~ tal'" ~\.\.\~taC£t .,",£, GROU\) In the legal profession, this is: . .11 , II Type in this address and instantly find yourself at considered the premier online address of the legal the center of the online legal universe. From this single profession. Or call 1-800-762-5272. address, you can network with colleagues and connect with prospective clients. West Group is working closely with the Utah State Bar to present a series of technology-oriented CLE seminars. Lawoffice.com'" from West Legal Directory": Utah State Bar members also receive a 10% discount Visit just once and you'll quickly see why it's already on all firm Web sites. Call today for details about both programs! .. .WEST GROUP Trademarks shown within are used under license. /§ 2000 West Group 1.9799.2/1-00 10688061 Table, of Contents a'he Presidents1Message: Jim Clegg (April 31, 1939-January 15, 2000) by Charles,. R. Brown 6 ~ "' The Beginner's Guide to Delinquency Representation by Katherine Bernards-Goodman 8 dot.com 101 (True Confessions of a Rookie Solo/Webmaster) by Cynthia Hale ~ of Life Issues: Organ and Tissue Donation ex McDonald Letters Submission Guidelines: ...¡ 1. Letters shal be tyewritten, double spaced, signed by the author Commissioners or any employee of the Utah State Bar to civil or criminal liabilty. and shall not exceed 300 words in length. 2. No one person shal have more than one letter to the editor pub- 6. No letter shall be published which advocates or opposes a par- lished every six months. ticular candidacy for a political or judicial office or which contains a solicitation or advertisement for a commercial or shal be addressed to Editor, 3. -

Practice Professional Will

BY TRACI M. SMITH Traci M. Smith is an estate plan- ning attorney for the law firm of Morris, Hall & Kinghorn, P.L.L.C. She graduated cum laude from Millsaps College and earned her Juris Doctor from the University of Arizona. She is a member of the American Academy of Estate Planning Attorneys and a noted speaker on the topics of estate planning and asset protec- tion. She can be reached at [email protected]. Deathof a Estate Planning With the Practice Professional Will As citizens in a culture that worships youth, most of us find it nearly impossible to admit our own mortality. Even fewer of us make plans for that eventuality. The same is true of attorneys. We spend much of our time advocating for our clients. Often, we are so consumed with our work and our daily activities that we frequently fail to plan for vaca- tions, much less develop an estate plan, one that prepares for incapacity and death. That is a crucial mistake. Fortunately, it is a reversible error. 36 ARIZONA ATTORNEY JUNE 2007 What’s The Harm? If a plan has not been established in the lawyers owe an affirmative duty to protect For the survivors of a deceased person, the case of incapacity or death, the State Bar of their clients’ interests.10 hours and days following a loved one’s Arizona is available as a resource to attor- What should that plan include? death is no time for important decisions. neys. In certain cases, the State Bar may be The State Bar and the American Bar This phenomenon is not unique to attor- named as a conservator under Rules 66 Association suggest that, at minimum, such neys. -

Informal Opinion 2012-06

30 Bank Street _,„, . -^ PO Box 350 COnneCtlCUt^L New Britain Bar Association % croeoswaso 06051 for 30 Bank Street P: (860) 223-4400 Professional Ethics Committee F: (860) 223-4488 Approved June 20, 2012 INFORMAL OPINION 2012-06 MAY COUNSEL AGREE TO HOLD A SETTLING DEFENDANT HARMLESS FROM THIRD PARTY LIENS IN CONNECTION WITH THE SETTLEMENT OF A CLIENT'S CLAIM? You indicate that you regularly represent individuals in personal injury actions. We understand that due, in part, to federal law requirements directing insurers to protect Medicare liens when settling claims, some insurers request that you execute indemnification agreements in connection with settlement of your client's claims. Typically, such an indemnification agreement would require you to hold harmless the settling defendants' against any claims arising out of federal, state or valid private liens against the personal injury settlement funds. You have asked whether such agreements violate the Rules of Professional Conduct. For several reasons, we conclude that the hold harmless and indemnification agreements you describe are prohibited by the Rules. First, Rule 1.7(b) provides that that "a lawyer shall not represent a client if the representation involves a concurrent conflict of interest," including situations where (2) "there is a significant risk that the representation of one or more clients will be materially limited by the lawyer's responsibilities to ... a third person or by a personal interest of the lawyer." The Committee finds that the indemnification agreements described present a conflict of interest between the plaintiffs attorney and his/her client, because it injects the lawyer's financial interests into the client's decision to settle. -

ISBA Professional Conduct Advisory Opinion ______

ISBA Professional Conduct Advisory Opinion ________________________________ Opinion No. 21-04 May 2021 Subject: Division of Fees; Referral Fees and Arrangements. Digest: An Illinois lawyer may enter into a fee-sharing agreement with an out-of-state lawyer who refers a personal injury case to the Illinois lawyer so long as the agreement complies with the applicable Illinois Rules of Professional Conduct and the corresponding rules of the foreign jurisdiction. References: Ill. R. Prof’l Conduct 1.5 (c)(e)(f)(g) In re Storment, 203 Ill.2d 378 (2002) ABA Formal Opinion 464 (2013) ABA Formal Opinion 316 (1967) State Bar of Michigan RI-199 (1994) Philadelphia Bar Association Opinion 93-15 (1993) State Bar of Arizona Ethics Opinion 10-04 (2010) Connecticut Bar Association Committee on Professional Ethics Opinion 91- 7 (Ct. 1991) Florida R. Prof’l Conduct 4-15(f)(4)(D) FACTS An out-of-state lawyer wishes to refer a personal injury case to an Illinois lawyer and the Illinois lawyer seeks to enter into a fee-sharing agreement with that lawyer. QUESTION Do the Illinois Rules of Professional Conduct permit an Illinois lawyer to enter into a fee- sharing agreement with an out-of-state lawyer and pay that lawyer a referral fee for a personal injury matter to be litigated in Illinois? DISCUSSION An Illinois lawyer may accept a personal injury matter from an out-of-state lawyer, enter into a fee-sharing agreement with that lawyer and pay that lawyer a referral fee. Illinois Rules of Professional Conduct Ruled 1.5(c) and (e) govern this query and do not prohibit the proposed fee- sharing agreement and corresponding referral fee. -

State Bar of Arizona :: Ethics Opinion

State Bar of Arizona :: Ethics Opinion Career Center Terms of Use En Español Select Language Member Login HomeFOR THEEthics PUBLIC EthicsFOR OpinionsLAWYERS EthicsABOUT Opinion US NEWS & EVENTS EthicsCONTACT OpinionsUS Rules of Professional State Bar of Arizona Ethics Conduct Opinions Ethics Committee 11-02: Internet; Advertising; Referral Service; Fee Sharing 10/2011 A lawyer may ethically participate in an Internet-based group advertising program that limits participation to a single lawyer for each ZIP code from which prospective clients may come, provided that the service fully and accurately discloses its advertising nature and, specifcally, that each lawyer has paid to be the sole lawyer lised in a particular ZIP code. To remain a permissible group advertising program, such a service may do nothing more to match clients with lawyers than to provide inquiring clients with the name and contact information of participating lawyers, without communicating any subsantive endorsement. The service will lose the protection aforded by the required disclosures and cross the line that disinguishes permissible advertising from an impermissible for-proft referral service if the required disclosures are difcult to fnd, read, or undersand; are contradicted by other messages on the website; or are made so late in the process that the consumer of legal services is unlikely to read them before contacting participating lawyers. A lawyer also may ethically participate in Internet advertising on a pay- per-click basis in which the advertising charge is based on the number of consumers who request information or otherwise respond to the lawyer’s advertisement, provided that the advertising charge is not based on the amount of fees ultimately paid by any clients who actually engage the lawyer.