Structural Brain Injury in Sports-Related Concussion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diagnoses to Include in the Problem List Whenever Applicable

Diagnoses to include in the problem list whenever applicable Tips: 1. Always say acute or open when applicable 2. Always relate to the original trauma 3. Always include acid-base abnormalities, AKI due to ATN, sodium/osmolality abnormalities 4. Address in the plan of your note 5. Do NOT say possible, potential, likely… Coders can only use a real diagnosis. Make a real diagnosis. Neurological/Psych: Head: 1. Skull fracture of vault – open vs closed 2. Basilar skull fracture 3. Facial fractures 4. Nerve injury____________ 5. LOC – include duration (max duration needed is >24 hrs) and whether they returned to neurological baseline 6. Concussion with or without return to baseline consciousness 7. DAI/severe concussion with or without return to baseline consciousness 8. Type of traumatic brain injury (hemorrhages and contusions) – include size a. Tiny = <0.6 cm b. Small/moderate = 0.6-1 cm c. Large/extensive = >1 cm 9. Cerebral contusion/hemorrhage 10. Cerebral edema 11. Brainstem compression 12. Anoxic brain injury 13. Seizures 14. Brain death Spine: 1. Cervical spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 2. Thoracic spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 3. Lumbar spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 4. Cord syndromes: central, anterior, or Brown-Sequard 5. Paraplegia or quadriplegia (any deficit in the upper extremity is consistent with quadriplegia) Cardiovascular: 1. Acute systolic heart failure 40 2. Acute diastolic heart failure 3. Chronic systolic heart failure 4. Chronic diastolic heart failure 5. Combined heart failure 6. Cardiac injury or vascular injuries 7. -

Two Types of Delayed Post-Traumatic Intracerebral Hematoma

Two Types of Delayed Post-Traumatic Intracerebral Hematoma Takashi TSUBOKAWA Department of Neurological Surgery, Nihon University School of Medicine, Tokyo 173 Summary The findings of repeated CT scans, clinicalcourses and pathologicalstudies in 28 cases of delayed post-traumatic intracerebral hematoma were studied retrospectivelyto elucidate the mechanism of bleeding and to establish adequate treatment. Based on the results obtained, it became clear that there are two types of delayed hematoma. In 10 of the 28 cases, initial CT findings within 6 hours after head injury revealed cerebral contusion or hemorrhagic contusion, and spots of high density scattered in the low density zone gradually became confluent to form an irregularly shaped hematoma according to follow-up CT findings. This was termed "hematoma within a contusional area." In 15 of the 28 cases, initial CT findings within 6 hours after head injury revealed no abnormal density within the brain and the hematoma appeared suddenly 3 6 days after the injury. In eight of the 15 cases, emergency surgery was performed for the removal of epidural or subdural hematoma. This type of hematoma is termed "contusional hem atoma" and constitutes the second group. In three of the 28 cases, both types of hematoma were observed. Based on histological findings for the two types of delayed hematoma. The first group may be induced by an anoxic vasodilation mechanism (Evans et al.9)), while the second group may be derived from a different mechanism related to ishemic changes and the free radical reaction caused by the reflow phenomenon (Tsubokawa et al.14-16)1 It is important to establish correct diagnoses 1for delayed hematomas based on differences between follow-up findings of repeated CT and an initial CT performed within 6 hours after head injury since the operative indications and operative results for the two groups are different as indicated by our 28 cases. -

Management of the Head Injury Patient

Management of the Head Injury Patient William Schecter, MD Epidemilogy • 1.6 million head injury patients in the U.S. annually • 250,000 head injury hospital admissions annually • 60,000 deaths • 70-90,000 permanent disability • Estimated cost: $100 billion per year Causes of Brain Injury • Motor Vehicle Accidents • Falls • Anoxic Encephalopathy • Penetrating Trauma • Air Embolus after blast injury • Ischemia • Intracerebral hemorrhage from Htn/aneurysm • Infection • tumor Brain Injury • Primary Brain Injury • Secondary Brain Injury Primary Brain Injury • Focal Brain Injury – Skull Fracture – Epidural Hematoma – Subdural Hematoma – Subarachnoid Hemorrhage – Intracerebral Hematorma – Cerebral Contusion • Diffuse Axonal Injury Fracture at the Base of the Skull Battle’s Sign • Periorbital Hematoma • Battle’s Sign • CSF Rhinorhea • CSF Otorrhea • Hemotympanum • Possible cranial nerve palsy http://health.allrefer.com/pictures-images/ Fracture of maxillary sinus causing CSF Rhinorrhea battles-sign-behind-the-ear.html Skull Fractures Non-depressed vs Depressed Open vs Closed Linear vs Egg Shell Linear and Depressed Normal Depressed http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2894.htm Temporal Bone Fracture http://www.vh.org/adult/provider/anatomy/ http://www.bartleby.com/107/illus510.html AnatomicVariants/Cardiovascular/Images0300/0386.html Epidural Hematoma http://www.chestjournal.org/cgi/content/full/122/2/699 http://www.bartleby.com/107/illus769.html Epidural Hematoma • Uncommon (<1% of all head injuries, 10% of post traumatic coma patients) • Located -

The Diagnosis of Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1990;53:365-372 365 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.53.5.365 on 1 May 1990. Downloaded from OCCASIONAL REVIEW The diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage M Vermeulen, J van Gijn Lumbar puncture (LP) has for a long time been of 55 patients with SAH who had LP, before the mainstay of diagnosis in patients who CT scanning and within 12 hours of the bleed. presented with symptoms or signs of subarach- Intracranial haematomas with brain shift was noid haemorrhage (SAH). At present, com- proven by operation or subsequent CT scan- puted tomography (CT) has replaced LP for ning in six of the seven patients, and it was this indication. In this review we shall outline suspected in the remaining patient who stop- the reasons for this change in diagnostic ped breathing at the end of the procedure.5 approach. In the first place, there are draw- Rebleeding may have occurred in some ofthese backs in starting with an LP. One of these is patients. that patients with SAH may harbour an We therefore agree with Hillman that it is intracerebral haematoma, even if they are fully advisable to perform a CT scan first in all conscious, and that withdrawal of cerebro- patients who present within 72 hours of a spinal fluid (CSF) may occasionally precipitate suspected SAH, even if this requires referral to brain shift and herniation. Another disadvan- another centre.4 tage of LP is the difficulty in distinguishing It could be argued that by first performing between a traumatic tap and true subarachnoid CT the diagnosis may be delayed and that this haemorrhage. -

Iatrogenic Spinal Subarachnoid Hematoma After Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture

https://doi.org/10.14245/kjs.2017.14.4.158 KJS Print ISSN 1738-2262 On-line ISSN 2093-6729 CASE REPORT Korean J Spine 14(4):158-161, 2017 www.e-kjs.org Iatrogenic Spinal Subarachnoid Hematoma after Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture Jung Hyun Park, Spinal subarachnoid hematoma (SSH) following diagnostic lumbar puncture is very rare. Generally, Jong Yeol Kim SSH is more likely to occur when the patient has coagulopathy or is undergoing anticoagulant therapy. Unlike the usual complications, such as headache, dizziness, and back pain at the Department of Neurosurgery, Kosin needle puncture site, SSH may result in permanent neurologic deficits if not properly treated University Gospel Hospital, Kosin within a short period of time. An otherwise healthy 43-year-old female with no predisposing University College of Medicine, factors presented with fever and headache. Diagnostic lumbar puncture was performed under Busan, Korea suspicion of acute meningitis. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging was performed due to hypo- Corresponding Author: esthesia below the level of T10 that rapidly progressed after the lumbar puncture. SSH was Jong Yeol Kim diagnosed, and high-dose steroid therapy was started. Her neurological symptoms rapidly deterio- Department of Neurosurgery, rated after 12 hours despite the steroids, necessitating emergent decompressive laminectomy Kosin University Gospel Hospital, and hematoma removal. The patient’s condition improved after the surgery from a preoperative Kosin University College of Medicine, 262 Gamcheon-ro, Seo-gu, Busan motor score of 1/5 in the right leg and 4/5 in the left leg to brace-free ambulation (motor grade 49267, Korea 5/5) 3-month postoperative. -

Sports-Related Concussions: Diagnosis, Complications, and Current Management Strategies

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 40 (4):E5, 2016 Sports-related concussions: diagnosis, complications, and current management strategies Jonathan G. Hobbs, MD,1 Jacob S. Young, BS,1 and Julian E. Bailes, MD2 1Department of Surgery, Section of Neurosurgery, The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago; and 2Department of Neurosurgery, NorthShore University HealthSystem, The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Evanston, Illinois Sports-related concussions (SRCs) are traumatic events that affect up to 3.8 million athletes per year. The initial diag- nosis and management is often instituted on the field of play by coaches, athletic trainers, and team physicians. SRCs are usually transient episodes of neurological dysfunction following a traumatic impact, with most symptoms resolving in 7–10 days; however, a small percentage of patients will suffer protracted symptoms for years after the event and may develop chronic neurodegenerative disease. Rarely, SRCs are associated with complications, such as skull fractures, epidural or subdural hematomas, and edema requiring neurosurgical evaluation. Current standards of care are based on a paradigm of rest and gradual return to play, with decisions driven by subjective and objective information gleaned from a detailed history and physical examination. Advanced imaging techniques such as functional MRI, and detailed understanding of the complex pathophysiological process underlying SRCs and how they affect the athletes acutely and long-term, may change the way physicians treat athletes who suffer a concussion. It is hoped that these advances will allow a more accurate assessment of when an athlete is truly safe to return to play, decreasing the risk of secondary impact injuries, and provide avenues for therapeutic strategies targeting the complex biochemical cascade that results from a traumatic injury to the brain. -

Feigned Consensus: Usurping the Law in Shaken Baby Syndrome/ Abusive Head Trauma Prosecutions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Michigan School of Law University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2020 Feigned Consensus: Usurping the Law in Shaken Baby Syndrome/ Abusive Head Trauma Prosecutions Keith A. Findley University of Wisconsin Law School D. Michael Risinger Seton Hall University School of Law Patrick D. Barnes Stanford University Medical Center Julie A. Mack Pennsylvania State University Medical Center David A. Moran University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2102 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Criminal Procedure Commons, Evidence Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Findley, Keith A. "Feigned Consensus: Usurping the Law in Shaken Baby Syndrome/Abusive Head Trauma Prosecutions." Michael Risinger, Patrick Barnes, Julie Mack, David A. Moran, Barry Scheck, and Thomas Bohan, co-authors. Wis. L. Rev. 2019, no. 4 (2019): 1211-268. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Keith A. Findley, D. Michael Risinger, Patrick D. Barnes, Julie A. Mack, David A. Moran, Barry C. Scheck, and Thomas L. Bohan This article is available at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2102 FEIGNED CONSENSUS: USURPING THE LAW IN SHAKEN BABY SYNDROME/ ABUSIVE HEAD TRAUMA PROSECUTIONS KEITH A. -

What to Expect After Having a Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) Information for Patients and Families Table of Contents

What to expect after having a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) Information for patients and families Table of contents What is a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)? .......................................... 3 What are the signs that I may have had an SAH? .................................. 4 How did I get this aneurysm? ..................................................................... 4 Why do aneurysms need to be treated?.................................................... 4 What is an angiogram? .................................................................................. 5 How are aneurysms repaired? ..................................................................... 6 What are common complications after having an SAH? ..................... 8 What is vasospasm? ...................................................................................... 8 What is hydrocephalus? ............................................................................... 10 What is hyponatremia? ................................................................................ 12 What happens as I begin to get better? .................................................... 13 What can I expect after I leave the hospital? .......................................... 13 How will the SAH change my health? ........................................................ 14 Will the SAH cause any long-term effects? ............................................. 14 How will my emotions be affected? .......................................................... 15 When should -

Overcoming Defense Expert Testimony in Abusive Head Trauma Cases

NATIONAL CENTER FOR PROSECUTION OF CHILD ABUSE Special Topics in Child Abuse Overcoming Defense Expert Testimony in Abusive Head Trauma Cases By Dermot Garrett Edited by Eleanor Odom, Amanda Appelbaum and David Pendle NATIONAL CENTER FOR PROSECUTION OF CHILD ABUSE Scott Burns Director , National District Attorneys Association The National District Attorneys Association is the oldest and largest professional organization representing criminal prosecutors in the world. Its members come from the offices of district attorneys, state’s attorneys, attorneys general, and county and city prosecutors with responsibility for prosecuting criminal violations in every state and territory of the United States. To accomplish this mission, NDAA serves as a nationwide, interdisciplinary resource center for training, research, technical assistance, and publications reflecting the highest standards and cutting-edge practices of the prosecutorial profession. In 1985, the National District Attorneys Association recognized the unique challenges of crimes involving child victims and established the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse (NCPCA). NCPCA’s mission is to reduce the number of children victimized and exploited by assisting prosecutors and allied professionals laboring on behalf of victims too small, scared or weak to protect themselves. Suzanna Tiapula Director, National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse A program of the National District Attorneys Association www.ndaa.org 703.549.9222 This project was supported by Grants #2010-CI-FX-K008 and [new VOCA grant #] awarded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention is a component of the Office of Justice Programs. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

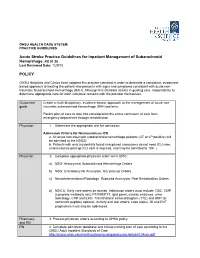

Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for Inpatient Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, PS 01.20 POLICY

OHSU HEALTH CARE SYSTEM PRACTICE GUIDELINES Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for Inpatient Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, PS 01.20 Last Reviewed Date: 1/29/10 POLICY OHSU Hospitals and Clinics have adopted this practice standard in order to delineate a consistent, evidenced- based approach to treating the patient who presents with signs and symptoms consistent with acute non- traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH). Although this standard assists in guiding care, responsibility to determine appropriate care for each individual remains with the provider themselves. Outcomes/ Create a multi-disciplinary, evidence-based, approach to the management of acute non- goals traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) patients. Patient plan of care to take into consideration the entire continuum of care from emergency department through rehabilitation. Physician 1. Determine the appropriate unit for admission. Admission Criteria for Neurosciences ICU a. All acute non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage patients (CT or LP positive) will be admitted to the NSICU. b. Patients with only incidentally found unruptured aneurysms do not need ICU care, unless routine post-op ICU care is required, and may be admitted to 10K. ( Physician 2. Complete appropriate physician order set in EPIC: a) NSG: Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Orders. b) NSG: Craniotomy for Aneurysm: ICU post-op Orders. c) NeuroInterventional Radiology: Ruptured Aneurysm: Post Embolization Orders. d) NSICU: Daily care orders on rounds. Admission orders must include: CBC, CMP (complete metabolic set), PT/INR/PTT, lipid panel, cardiac enzymes, urine toxicology, CXR and EKG. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and BNP (B- natriuretic peptide) optional. Activity and diet orders, code status, GI and DVT prophylaxis must also be addressed. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Neuropathol Exp Neurol

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 September 24. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009 July ; 68(7): 709±735. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes: Progressive Tauopathy following Repetitive Head Injury Ann C. McKee, MD1,2,3,4, Robert C. Cantu, MD3,5,6,7, Christopher J. Nowinski, AB3,5, E. Tessa Hedley-Whyte, MD8, Brandon E. Gavett, PhD1, Andrew E. Budson, MD1,4, Veronica E. Santini, MD1, Hyo-Soon Lee, MD1, Caroline A. Kubilus1,3, and Robert A. Stern, PhD1,3 1 Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 2 Department of Pathology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 3 Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 4 Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center, Bedford Veterans Administration Medical Center, Bedford, Massachusetts 5 Sports Legacy Institute, Waltham, MA 6 Department of Neurosurgery, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 7 Department of Neurosurgery, Emerson Hospital, Concord, MA 8 CS Kubik Laboratory for Neuropathology, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts Abstract Since the 1920s, it has been known that the repetitive brain trauma associated with boxing may produce a progressive neurological deterioration, originally termed “dementia pugilistica” and more recently, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). We review the 47 cases of neuropathologically verified CTE recorded in the literature and document the detailed findings of CTE in 3 professional athletes: one football player and 2 boxers. -

Simultaneous Cranial Subarachnoid Hemorrhage-Subdural Hematoma

Case Report/Olgu Sunumu İstanbul Med J 2021; 22(1): 81-3 DO I: 10.4274/imj.galenos.2020.73658 Simultaneous Cranial Subarachnoid Hemorrhage-Subdural Hematoma and Spinal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Eşzamanlı Kraniyal Subaraknoid Kanama-Subdural Hematom ve Spinal Subaraknoid Kanama Hatice Kaplanoğlu1, Veysel Kaplanoğlu2, Aynur Turan1, Onur Karacif1 1University of Health Sciences Turkey, Dışkapı Yıldırım Beyazıt Training and Research Hospital, Clinic of Radiology, Ankara, Turkey 2University of Health Sciences Turkey, Keçiören Training and Research Hospital, Clinic of Radiology, Ankara, Turkey ABSTRACT ÖZ Patients with traumatic intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage Çok nadiren, travmatik intrakraniyal subaraknoid hemorojisi (SAH) rarely develop spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SSAH) (SAH) olan hastalarda, doğrudan omurga yaralanması olmadan without direct spinal injury. We present the case of a 76-year- spinal subaraknoid kanama (SSAH) ortaya çıkabilir. Travmatik old male patient with traumatic intracranial SAH and subdural intrakraniyal SAH ve subdural hematomu olan 76 yaşındaki hematoma, back pain and weakness in the both lower erkek hastada, yoğun bakım takibi sırasında travmadan üç gün limbs radiating to the legs three days after the trauma. After sonra bacaklarına yayılan sırt ağrısı ve bilateral alt ekstremitede worsening of pain and numbness, the patient underwent a güçsüzlük ortaya çıktı. Ağrı ve uyuşmanın kötüleşmesi üzerine, lumbar magnetic resonance imaging 7 days after the trauma, travmadan 7 gün sonra hastaya lomber manyetik rezonans in which blood was seen in the spinal canal in the lumbosacral görüntüleme yapıldı. Lumbosakral bölgede intraspinal region. The bleeding was considered SSAH because of the kanama görüldü. Kanamanın sıvı seviyesi göstermesi liquid level. The patient underwent conservative treatment sebebiyle SSAH olarak değerlendirildi. Hasta kardiyak açıdan because the patient was found to be at high cardiac risk and yüksek riskli bulunduğu için ve nörolojik defisiti hafif olduğu the neurological deficit was mild.