Creative Writing Practice and Pedagogy: a Jungian Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Fall Submission Calls from Rattle

News from the Feminist Caucus, by Anne Burke This month submission calls from Rattle Tribute to Feminist Poets by Oct. 15 & Caitlin Press on "Boobs: Women Explore What It Means to Have Breasts", due Oct. 12; news from Penn Kemp on Gwendolyn MacEwen and Milton Acorn honouring. The Wordspell is a new spoken word group that came together in spring 2012 with the goal of creating a poetry series in Toronto that focuses on women’s voices; Girls Art League; The Feminist Art Conference on Facebook; introducing Anita Dolman and a review of Foreign Skin , by Kate Rogers. The NDP government will “build feminism in Alberta,” according to the province’s Status of Women minister. The Canadian Women Studies: Women and Water is forthcoming May 2015/Fall Winter 2015; Women Writing 4: Remembering is the current issue with many familiar names. Calls for Submissions Your Fall Submission Calls from Rattle https://rattle.submittable.com/submit/28744 Feminist Poets | Deadline: October 15th The Spring 2016 issue will feature a tribute to Feminist Poets. The poems may be written in any style, subject, or length, but must be written by those who identify as Feminist Poets and use poetry to advocate for women's rights. Please explain how this applies to you in your contributor note. The poems themselves don't have to be about feminism or women's rights - we want to explore the range of work that contemporary Feminist Poets are producing. To send up to four poems, click here . Please submit up to four poems (or pages of short poems) at the same time, but these must be sent as a single submission in ONE document. -

Ruth Panofsky Address: Department of English Member of the Graduate Faculty Ryerson University 350 Victoria Street Toronto, Ontario M5B 2K3 416 979 5000 Ext

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Ruth Panofsky Address: Department of English Member of the Graduate Faculty Ryerson University 350 Victoria Street Toronto, Ontario M5B 2K3 416 979 5000 ext. 6150 416 979 5387 fax [email protected] Position: . Professor . Research Associate, Modern Literature and Culture Research Centre . Member, Centre for Digital Humanities Citizenship: Canadian Languages: English, French EDUCATION: PhD, York University, English 1991 Examinations: First field: Canadian Literature Second field: Novel and Other Narrative Dissertation: A Bibliographical Study of Thomas Chandler Haliburton’s The Clockmaker, First, Second, and Third Series Supervisor: Professor John Lennox MA, York University, English 1982 MRP: Studies in the Early Poetry of Miriam Waddington Supervisor: Professor John Lennox BA Honours, Carleton University, English 1980 First year, Vanier College, Social Sciences 1976 AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS (EXTERNAL): 2016 Rosa and the late David Finestone Canadian Jewish Studies Award for Best Book in English or French, J. I. Segal Awards, Jewish Public Library ($500) 2016 Finalist, Vine Awards for Canadian Jewish Literature 2015 Canadian Jewish Literary Award for Yiddish Culture ($1,000) 2015 PROSE Award for Literature, Professional and Scholarly Publishing Division, Association of American Publishers 2015 Finalist, Eric Hoffer Award for Independent Books 2 – Ruth Panofsky 2013 McCorison Fellowship for the History and Bibliography of Printing in Canada and the United States, Bibliographical Society of America ($2,000US) 2011-14 -

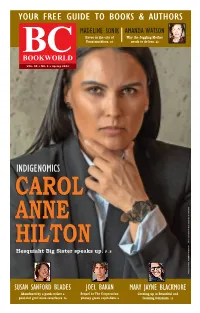

Spring 2021 Volume 35

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS MADELINE SONIK AMANDA WATSON Havoc in the city of Why the Juggling Mother Fountainebleau. 24 needs to do less. 22 BCBOOKWORLD VOL. 35 • NO. 1 • Spring 2021 INDIGENOMICS CAROLCAROL PRODUCTIONS EYE SALISH ANNEANNE , THOMAS TRICIA BY HILTONHILTON PHOTO #40010086 Hesquiaht Big Sister speaks up. P.8 AGREEMENT MAIL PUBLICATION SUSAN SANFORD BLADES JOEL BAKAN MARY JAYNE BLACKMORE Abandoned by a punk rocker a Sequel to The Corporation: Growing up in Bountiful and post-riot grrrl mom resurfaces. 26 phoney green capitalism. 6 learning feminism. 13 PRINTED??????/TARA / BEV It’s a Great Season to Buy Local Good Morning, Takaya Takaya’s Journey Time to Wonder – Volume 1 Birding for Kids Cheryl Alexander and Alex Van Tol Cheryl Alexander and Jenaya Copithorne Sue Harper and S. Lesley Buxton A Guide to Finding, Identifying, and Photographing Birds in Your Area The remarkable story of Vancouver Told in verse and containing details of A colourful, fun, and fact-filled kid’s Damon Calderwood and Donald E. Waite Island’s lone wolf, Takaya, is told in this Takaya’s life, this picture book introduces guide to BC’s regional museums in charming, lyrical picture book for infants. young readers to Takaya, the lone wolf. the Thompson-Okanagan, Kootenays, A fun, educational guide to watching birds $12 bb | $10 pb | $5.99 ebook $20 hc | $15 pb | $9.99 ebook and Cariboo-Chilcotin. in their natural habitat. RMB | Rocky Mountain Books RMB | Rocky Mountain Books $22 pb | $10.99 ebook $19.95 pb | $15.99 ebook RMB | Rocky Mountain Books -

TREK the Magazine of the University of British Columbia

ISSUE NUMBER 30 FALL/WINTER 2011 TREK THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA A UBC PRof’S LETTER FROM THE ARCTIC 28 SEX, DRUGS, AND ROCKING CHAIRS: THE BOOMERS RETire 12 · PlighT OF THE Honey Bee 16 THE UBC JANITOR WHO BECAME A MUSEUM CURATor 21 UBC STARts AN EVOLUTion 32 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ALUMNI AssOCIATION CONTENTS: FEATURES DEPARTMENTS TREK EDITOR Vanessa Clarke, BA ART DIREctOR Keith Leinweber, BDes 21 Old Bill 5 Take Note 34 Alumni Events 45 T-Bird News CONTRIBUTOR Michael Awmack, BA’01, MET’09 How a much-loved early UBC people are documenting BOARD OF DIREctORS CHAIR Judy Rogers, BRE’71 UBC janitor became a global access to morphine, 36 Class Acts 47 In Memoriam VICE CHAIR Dallas Leung, BCom’94 museum curator cleaning up the aftermath of TREASURER Ian Warner, BCom’89 MEMBERS AT LARGE ’09-’12 mining activities, and helping 42 Book Reviews Aderita Guerreiro, BA’77 youth to quit smoking. Mark Mawhinney, BA’94 MEMBERS AT LARGE ’10-’13 Carmen Lee, BA’01 Michael Lee, BSC’86, BA’89, MA’92, LLB MEMBERS AT LARGE ’11-’14 Brent Cameron, BA, MBA’06 Ernest Yee, BA’83, MA’87 Blake Hanna, MBA’82 24 Redefining Robert Bruno, BCom’97 PAST CHAIR ’11-’12 Justice What the Trek? Miranda Lam, LLB’02 Trek Magazine caption competition AMS REPRESENTATIVE ’11-’12 Professor Frank Tester Jeremy McElroy, BASC‘07 promotes a community-based Send us your caption for Trek designer Keith Leinweber’s latest cartoon and you could win a rare and CONVOCATION SENATE REP. -

· Contributors

· CoNTRIBUTORs CHRIS fu'\/DREWS teaches French at the Cniversity of Melbourne, has pub lished poems in a variety of Australian journals, and is the translator of Full Circle: A Soutb Americanjourney(l996) by the Chilean novel ist Luis SepCdveda. LEANNE A'v'ERBACH teaches English at the University of British Col umbia Lan guage institute. Her poetry has been published in Descant, The rlntigonisb ReL'iew, Tbe Dalhousie Review, and SubTERRAIN BLANCA BAQUERO, a resident of Sept-Iles, Quebec, and mother of four, has had poetry published in Por1als /Vfagazine. Eueryman: A i\lfen 'sjour nal, Eclectic Literary Forum. and various other journals. lVL<~.RTIN BENNETT lives in Saudi Arabia. His work has been broadcast on BBC Radio and published in Stand, Poetry Ireland Reuiew, Honest Ulster man, Oxford Poet1y, Descant. and West Aji"ica. LAURA DEST li ve;, iu East Dalhousie, Nova Scotia. IIer work can be seen in Green's Magazine. Tbe Gaspereau Review, The Antigonish Review, and The Amethyst Review. ]ESS BOND, who grew up in Cape Breton, is a former schoolteacher whose work has been published in The Prairie journal and The A ntigonish Revieu ·. GILBERT A. BouCHARD is an Edmonton-based poet, journalist, broadcaster, publicist, and corporate writer. He is currently working on a volume of poetry titled "The Shadow Box Poems ... ELIZABETH BREWSTER has more than twenty books of fiction and poetty to her credit. including Footnotes to the Book ofjob, which was shortlisted for the Governor General's Award in 1996. Her most recent poetry collection is titled Garden ofSculpture (1998). RoNNIE R. -

Inanna Publications & Education Inc

Inanna Publications & Education Inc. Celebrating Over 42 Years of Smart books for Feminist Publishing people who want Inanna Publications & Education Inc. is one of only a very few independent feminist presses in Canada committed to publishing fiction, poetry, and cre- to read and think ative non-fiction by and about women, and complementing this with relevant about real non-fiction. Inanna’s list fosters new, innovative and diverse perspectives with the potential to change and enhance women’s lives everywhere. Our aim is women’s lives. to conserve a publishing space dedicated to feminist voices that provoke discussion, advance feminist thought, and speak to diverse lives of women. Founded in 1978, and housed at York University since 1984, Inanna is the proud publisher of one of Canada’s oldest feminist journals, Canadian Wom- an Studies/les cahiers de la femme. Our priority is to publish literary books, particularly by fresh, new Canadi- an voices, that are intellectually rigorous, speak to women’s hearts, and tell truths about the vital lives of a broad diversity of women—smart books for people who want to read and think about real women’s lives. Inanna books are important resources, widely used in university courses across the country. Our books are essential for any curriculum and are indispensable Spring 2020 resources for the feminist reader. Inanna Publications & Education Inc. C O N T E N T S SPRING 2020 FRontLIST: INANNA POETRY AND FICTIon SERIES 2 SPRING 2020 non-FICTIon 17 2019 INANNA POETRY AND FICTIon SERIES 18 2019 INANNA MEMOIR SERIES 30 INANNA MEMOIR SERIES HIGHLIGHTS 31 2019 INANNA non-FICTIon 32 INANNA non-FICTIon HIGHLIGHTS 34 INANNA YOUNG FEMINIST SERIES HIGHLIGHTS 35 INANNA AWARD-WINNER HIGHLIGHTS 36 INANNA TITLES INDEX 41 Inanna Publications and Education Inc. -

Anvil Press New Books Fall 2021

32 years Anvil nvil Press A ressNew Books Fall 2021 New PBooks 20 FALL 21 Contemporary Canadian Literature “Literature is where I go to explore the highest and lowest places in human society and in the human spirit, where I hope to find not absolute truth but the truth of the tale, of the imagination and of the heart.” —Salman Rushdie “Literature is strewn with the wreckage of those who have minded beyond reason the opinion of others.” —Virginia Woolf We thank our cultural funders for their ongoing support: anvilpress.com 32 Non-Fiction Anvil Press • Autumn 2021 The Acid Room: The Psychedelic Trials and Tribulations of Hollywood Hospital by Jesse Donaldson & Erika Dyck 49.2 Series, #3 From the street, New Westminster’s Hollywood Hospital didn’t look like much. Just a rambling white mansion, mostly obscured behind the holly trees from which it took its name. But, between 1957 and 1968, it served as a mecca for alcoholics, anxi- ety patients, and unhappy couples, its unorthodox methods boasting a success rate of 50-80%, and attracting scores of celebrity patients, in- cluding Andy Williams, Cary Grant, and Ethel Kennedy. Those same methods would eventually bring about the facility’s downfall, as well Also in the 49.2 Series as the condemnation of physicians, the government, and the police. Land of Destiny 978-1-77214-144-3 Fool’s Gold 978-1-77214-146-7 Because, for the better part of a decade, Hollywood Hospital was the site of more than 6000 supervised LSD trips. Under the care of psychiatrist J. -

ENGLISH GRADUATE HANDBOOK 2017-2018 University of Windsor

ENGLISH GRADUATE HANDBOOK 2017-2018 University of Windsor Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The University of Windsor ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 The Department of English .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Library Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 5 1.4 Housing ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 THE M.A. IN ENGLISH ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Programs of Study ........................................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 The MA. in English: Language and Literature ............................................................................................. 5 1.3 The M.A. in English: Creative Writing and Language and Literature ......................................................... 6 1.4 Thesis and Project Deadlines ...................................................................................................................... -

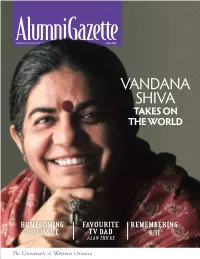

Vandana Shiva Take S on the World

AlumniGazetteWESTERn’S ALUMNI MaGAZINE SINCE 1939 SPRINGFALL 20102011 VANDANA SHIVA TAKE S ON THE WORLD HOMECOMING FAVOURITE REMEMBERING 2011 ISSUE TV DAD 9/11 ALAN THICKE AlumniGazette CONTENTS COUD L ALAN THICKE 11 BE THE WORLD’S FAVOURITE TV DAD? Profile of multi-talented Western alumnus BY JASON WINDERS, MES’10 S EEDS OF THE FUTURE 12 Vandana Shiva, PhD’79, LLD’02, takes on the world BY JASON WINDERS, MES’10 REMEMBERING 9/11, 14 10 YEARS LATER Reflections of Western alumni who experienced the attack You don’t need a better F ROM BOARDROOMS 20 TO BODICES… Beverly Behan, HBA’81, LLB’84, Financial Advisor. makes Canada’s history sexy BY DAVID SCOTT You need a great one. ALLE IN TH FAMILY 22 Western’s multi-generation graduates BY DAVID DAUPHINEE Like any great relationship, this one takes Just log on to www.accretiveadvisor.com hard work. and use the “Investor Discovery™” to On the cover: Indian philosopher, environmental activist and lead you to the Financial Advisor who’s eco-feminist Vandana Shiva, PhD’79, LLD’02, has made her Choosing the right Advisor is the key to best for you and your family. impact around the world. (Photo by Nitin Rai) a richer life in every way. 12 After all, the only thing at stake here But to get what you deserve, you need DEPARTMENTS is the rest of your financial life. alumnigazette.ca to act. Right now wouldn’t be a moment @ 05 LETTERS 33 MEMORIES WINNIPEG’S RETURN TO NHL HOCKEY too soon. www.accretiveadvisor.com H onour Society existed T radition of pranks keeps By Edward Fraser, BA’03, MA’04, Managing Editor, The Hockey News before 1952 campus on its toes BY ALAN NOON CYBORG TRADING SYSTEMS PRODUCES 08 CAMPUS NEWS SOFTWARE FOR HIGh-FREQUENCY TRADERS Labatt’s history home at 34 NEW RELEASES By Christopher Clark BA’88, MA’92 Western archives T he White Luck Warrior by T HOU DOTH PROTEST: PEACEFUL PROTEST OR R. -

Inanna Publications & Education Inc

Inanna Publications & Education Inc. Celebrating Over 43 Years of Smart books for Feminist Publishing people who want Inanna Publications & Education Inc. is one of only a very few independent feminist presses in Canada committed to publishing fiction, poetry, and cre- to read and think ative non-fiction by and about women, and complementing this with relevant about real non-fiction. Inanna’s list fosters new, innovative and diverse perspectives with the potential to change and enhance women’s lives everywhere. Our aim is women’s lives. to conserve a publishing space dedicated to feminist voices that provoke discussion, advance feminist thought, and speak to diverse lives of women. Founded in 1978, and housed at York University since 1984, Inanna is the proud publisher of one of Canada’s oldest feminist journals, Canadian Wom- an Studies/les cahiers de la femme. Our priority is to publish literary books, particularly by fresh, new Canadi- an voices, that are intellectually rigorous, speak to women’s hearts, and tell truths about the vital lives of a broad diversity of women—smart books for people who want to read and think about real women’s lives. Inanna books are important resources, widely used in university courses across the country. Our books are essential for any curriculum and are indispensable Spring 2021 resources for the feminist reader. Inanna Publications & Education Inc. C O N T E N T S SPRING 2021 FRontLIST: POETRY AND FICTIon SERIES 2 SPRING 2021 FRontLIST: YOUNG FEMINIST SERIES 10 SPRING 2021 FRontLIST: F.A.R. ART SERIES 11 SPRING 2021 FRontLIST: MEMOIR SERIES 12 SPRING 2021 FRontLIST: SIGNATURE SERIES 14 2020 INANNA POETRY AND FICTIon SERIES 15 2020 INANNA non-FICTIon 25 non-FICTIon HIGHLIGHTS 26 INANNA AWARD-WINNER HIGHLIGHTS 28 INANNA TITLES INDEX 37 Inanna Publications and Education Inc. -

Department of English Language, Literature & Creative Writing

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH GRADUATE LANGUAGE, HANDBOOK LITERATURE & 2018-2019 CREATIVE WRITING 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE UNIVERSITY OF WINDSOR 4 LIBRARY RESOURCES 4 THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH 5 IN-HOUSE PUBLICATIONS 5 WRITER-IN-RESIDENCE 5 READING SERIES 5 THE M.A. IN ENGLISH M.A.: LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 6 M.A.: CREATIVE WRITING AND LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 7 THESIS AND PROJECT DEADLINES 8 SCHOLARSHIP AND THE PROFESSION 8 NON-ENGLISH COURSES 8 DURATION OF STUDY AND TIME TO COMPLETION 8 ADMISSION TO GRADUATE STUDIES IN ENGLISH ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS 9 APPLICATION MATERIALS 9 APPLICATION DEADLINES 10 FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE ENTRANCE SCHOLARSHIPS 11 EXTERNAL SCHOLARSHIPS 11 INTERNAL AWARDS 12 3 GRADUATE ASSISTANTSHIPS 13 GRADUATE COURSES GRADUATE SEMINARS 13 GRADING 13 LIST OF GRADUATE SEMINARS 14 2018-2019 PROPOSED GRADUATE SEMINARS INTERSESSION 2018 0126-550: LITERATURE OF THE 20TH CENTURY 15 FALL 2018 0126-525: TOPICS IN RENAISSANCE DRAMA 16 0126-535: LITERATURE OF RESTORATION AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURY 17 0126-596: COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY- THEORY AND PRACTICE 18 WINTER 2019 0126-555: AMERICAN LITERATURE 19 0126-570: LITERARY GENRES- POETRY 21 FALL 2018 & WINTER 2019 0126-591/592: CREATIVE WRITING SEMINAR A&B 22 ENGLISH GRADUATE FACULTY 23 CONTACT INFORMATION 24 4 INTRODUCTION THE UNIVERSITY OF WINDSOR Situated at the western end of Lake St. Clair, on the Detroit River, the University of Windsor is Canada’s southernmost university. The strategic location on the Canada-U.S. border at the centre of the Great Lakes- and in the manufacturing heartland of North America- provides a special focus for academic research initiatives in such area as the environment, the automotive sector, and social justice.