The Production of Popular Music As a Confidence Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

The Importance of Being Digital Paul Lansky 3/19/04 Tart-Lecture 2004

The Importance of Being Digital Paul Lansky 3/19/04 tART-lecture 2004 commissioneed by the tART Foundation in Enschede and the Gaudeamus Foundation in Amsterdam Over the past twenty years or so the representation, storage and processing of sound has moved from analog to digital formats. About ten years audio and computing technologies converged. It is my contention that this represents a significant event in the history of music. I begin with some anecdotes. My relation to the digital processing and music begins in the early 1970’s when I started working intensively on computer synthesis using Princeton University’s IBM 360/91 mainframe. I had never been interested in working with analog synthesizers or creating tape music in a studio. The attraction of the computer lay in the apparently unlimited control it offered. No longer were we subject to the dangers of razor blades when splicing tape or to drifting pots on analog synthesizers. It seemed simple: any sound we could describe, we could create. Those of us at Princeton who were caught up in serialism, moreover, were particularly interested in precise control over pitch and rhythm. We could now realize configurations that were easy to hear but difficult and perhaps even impossible to perform by normal human means. But, the process of bringing our digital sound into the real world was laborious and sloppy. First, we communicated with the Big Blue Machine, as we sometimes called it, via punch cards: certainly not a very effective interface. Next, we had a small lab in the Engineering Quadrangle that we used for digital- analog and analog-digital conversion. -

Blues Notes June 2016

VOLUME TWENTY-ONE, NUMBER SIX • JUNE 2016 Sunday, June 5th @ 5 pm - Zoo Bar CURTIS SALGADO Tuesday, June 7th @ 6 pm • 21st Saloon, Omaha, NE $10 for BSO members, $20 for non-members Join the BSO or renew at the door Advance tix @ www.eventbrite.com GOLDEN STATE - LONE STAR REVUE Also Appearing Thursday, June 30th @ 5 pm $15 Wednesday, June 8th @ 6 pm • Zoo Bar, Lincoln, NE 21st Saloon, Omaha WEEKLY BLUES SERIES 4727 S 96th Plaza SOARING WINGS BLUES FESTIVAL Thurs. shows @ 6pm • Sat. shows @ 8 pm with John Primer & Watermelon Slim Bands subject to change Saturday, June 4th June 2nd .............................................................Davy Knowles ($10) June 4th (8 pm) ... Swamp Productions Presents Swampboy Blues Band, SUMMER ARTS FESTIVAL Sweet Tea, Bad Judgement & 40 Sinners ($5) June 10, 11, & 12 June 7th (Tues)........................................................... Curtis Salgado Featuring ($10 BSO Members, $20 Non Members, Bernard Allison Friday, June10th advance tickets at www.eventbrite.com) June 9th (5 pm) ......................................... Tale of 3 Cities Tour ($10) BLUES AT BEL AIR Hector Anchondo, Amanda Fish, and Delta Sol - Sunday June 12th Front and Center opens at 5pm! featuring June 10th (9 pm) ........Achilles Last Stand - Led Zepplin Tribute ($5) The Mighty Jailbreakers June 11th (8 pm) .... Luther James Band ($5) Summer Arts Fest After Party and The Bel Airs June 16th (5 pm) .......... Markey Blue ($10) - Dilemma opens at 5pm June 18th (8 pm) ........ Blue House and the Rent to Own Horns ($5) BRIDGE BEATS June 23rd (5 pm) ....Bruce Katz Band ($10) - Far & Wide opens at 5pm Saturday June 10th & 24th June 25th (8 pm) ............................................Rhythm Collective ($5) June 30th (5 pm) ................... -

Memphis, Tennessee, Is Known As the Home of The

Memphis, Tennessee, is known as the Home of the Blues for a reason: Hundreds of bluesmen honed their craft in the city, playing music in Handy Park and in the alleyways that branch off Beale Street, plying their trade in that street’s raucous nightclubs and in juke joints across the Mississippi River. Mississippians like Ike Turner, B.B. King, and Howlin’ Wolf all passed through the Bluff City, often pausing to cut a record before migrating northward to a better life. Other musicians stayed in Memphis, bristling at the idea of starting over in unfamiliar cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and Los Angeles. Drummer Finas Newborn was one of the latter – as a bandleader and the father of pianist Phineas and guitarist Calvin Newborn, and as the proprietor of his own musical instrument store on Beale Street, he preferred the familiar environs of Memphis. Finas’ sons literally grew up with musical instruments in their hands. While they were still attending elementary school, the two took first prize at the Palace Theater’s “Amateur Night” show, where Calvin brought down the house singing “Your Mama’s On the Bottom, Papa’s On Top, Sister’s In the Kitchen Hollerin’ ‘When They Gon’ Stop.’” Before Calvin followed his brother Phineas to New York to pursue a jazz career, he interacted with all the major players on Memphis’ blues scene. In fact, B.B. King helped Calvin pick out his first guitar. The favor was repaid when the entire Newborn family backed King on his first recording, “Three O’ Clock Blues,” recorded for the Bullet label at Sam Phillips’ Recording Service in downtown Memphis. -

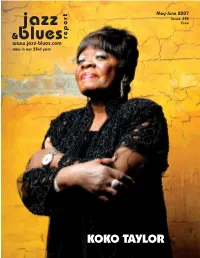

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

January 2021 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

Bluesletter J W B S . Nick Vigarino Still Rocks the House! Live at the US Embassy: Blues Happy Hour Remembering Jimmy Holden LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Hi Blues Fans, Proud Recipient of a 2009 I’m opening my letter with Keeping the Blues Alive Award another remembrance of another friend lost in our 2021 OFFICERS blues community. I have had to President, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org do this a few too many times Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected]@wablues.org lately and it is a reminder of Secretary, Marisue Thomas [email protected]@wablues.org how fragile life is and how Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected]@wablues.org important it is to live every day Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected]@wablues.org and make as many memories as you can. 2021 DIRECTORS Jimmy Holden passed away recently. I know there are many music Music Director, Open [email protected]@wablues.org fans who have great memories of Jimmy and his many performances Membership, Chad Creamer [email protected]@wablues.org and he touched many hearts with warmth, humor and melody. I will Education, Open [email protected]@wablues.org miss Jimmy for all of his wonderful stories about his travels. He Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected]@wablues.org traveled far and wide and we shared experiences we had both had Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org in multiple different localities around the world. Our conversations Advertising, Open [email protected]@wablues.org often lead to stories about adventures in Hong Kong, Thailand and other exotic places. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Johnny Cash by Dave Hoekstra Sept

Johnny Cash by Dave Hoekstra Sept. 11, 1988 HENDERSONVILLE, Tenn. A slow drive from the new steel-and-glass Nashville airport to the old stone-and-timber House of Cash in Hendersonville absorbs a lot of passionate land. A couple of folks have pulled over to inspect a black honky-tonk piano that has been dumped along the roadway. Cabbie Harold Pylant tells me I am the same age Jesus Christ was when he was crucified. Of course, this is before Pylant hands over a liter bottle of ice water that has been blessed by St. Peter. This is life close to the earth. Johnny Cash has spent most of his 56 years near the earth, spiritually and physically. He was born in a three-room railroad shack in Kingsland, Ark. Father Ray Cash was an indigent farmer who, when unable to live off the black dirt, worked on the railroad, picked cotton, chopped wood and became a hobo laborer. Under a New Deal program, the Cash family moved to a more fertile northeastern Arkansas in 1935, where Johnny began work as a child laborer on his dad's 20-acre cotton farm. By the time he was 14, Johnny Cash was making $2.50 a day as a water boy for work gangs along the Tyronza River. "The hard work on the farm is not anything I've ever missed," Cash admitted in a country conversation at his House of Cash offices here, with Tom T. Hall on the turntable and an autographed picture of Emmylou Harris on the wall. -

BBB-2017E.Pdf

Big Blues Bender Official Program 2017 1 Welcome to the Bender! It’s our honor and privilege to welcome you all to the 4th installment of the Big Blues Bender! To our veterans, we hope you can see the attention we have given to the feedback from our community to make this event even better, year after year. To the virgins, welcome to the family - you’re one of us now! You’ll be hard pressed to find a more fun-loving, friendly, and all around excellent group of people than are surrounding you this week. Make new friends of your fellow guests, and be sure to come say hi to all of us. We are here to make your experience the best it can be, and we’re excited to prove it! Finally, we would like to acknowledge the hard work and support of the Plaza Hotel staff and CEO Jonathan Jossel. We could not ask for a better team to make the Bender feel at home. -Much Love, Team Bender BENDER SUPPORT PRE & POST HOURS : Wed, 9/6: 12:00p-11:00p • Mon, 9/11: 10:00a-12:00p PANELS & PARTIES Appear in yellow on the schedule Bender Party With H.A.R.T • Wed, Sept. 6 • 8:00p • Showroom $30 GA - The Official Bender Pre-party is proud to support H.A.R.T. 100% of proceeds benefit the Handy Artists Relief Trust. Veterans Welcome the Virgins Party! • Thu, Sept. 7 • 4:00p • Pool Join Bender veteran and host, Marice Maples, in welcoming this year’s crop of Bender Virgins! The F.A.C.E Of Women In Blues Panel • Fri, Sept. -

Sweet & Lowdown Repertoire

SWEET & LOWDOWN REPERTOIRE COUNTRY 87 Southbound – Wayne Hancock Johnny Yuma – Johnny Cash Always Late with Your Kisses – Lefty Jolene – Dolly Parton Frizzell Keep on Truckin’ Big River – Johnny Cash Lonesome Town – Ricky Nelson Blistered – Johnny Cash Long Black Veil Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain – E Willie Lost Highway – Hank Williams Nelson Lover's Rock – Johnny Horton Bright Lights and Blonde... – Ray Price Lovesick Blues – Hank Williams Bring It on Down – Bob Wills Mama Tried – Merle Haggard Cannonball Blues – Carter Family Memphis Yodel – Jimmy Rodgers Cannonball Rag – Muleskinner Blues – Jimmie Rodgers Cocaine Blues – Johnny Cash My Bucket's Got a Hole in It – Hank Cowboys Sweetheart – Patsy Montana Williams Crazy – Patsy Cline Nine Pound Hammer – Merle Travis Dark as a Dungeon – Merle Travis One Woman Man – Johnny Horton Delhia – Johnny Cash Orange Blossom Special – Johnny Cash Doin’ My Time – Flatt And Scruggs Pistol Packin Mama – Al Dexter Don't Ever Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Please Don't Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Don't Take Your Guns to Town – Johnny Poncho Pony – Patsy Montana Cash Ramblin' Man – Hank Williams Folsom Prison Blues – Johnny Cash Ring of Fire – Johnny Cash Ghost Riders in the Sky – Johnny Cash Sadie Brown – Jimmie Rodgers Hello Darlin – Conway Twitty Setting the Woods on Fire – Hank Williams Hey Good Lookin’ – Hank Williams Sitting on Top of the World Home of the Blues – Johnny Cash Sixteen Tons – Merle Travis Honky Tonk Man – Johnny Horton Steel Guitar Rag Honky Tonkin' – Hank Williams Sunday Morning Coming -

Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 048 457 VT 012 300 AUTHOR Doeringer, Peter B.; Piore, Michael J. TITLE Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis. INSTITUTION Harvard Univ., Cambridge, Mass.; Massachusetts Inst. of Tech., Cambridge. SPONS AGENCY Manpower Administration (DOL), Washington, D.C. Office of Manpower Research. PUB DATE May 70 NOTE 344p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS *Business, Disadvantaged Groups, *Economic Research, Employment Opportunities, *Labor Economics, *Labor Market, Models, *Unemployment ABSTRACT Using data gathered in a series of interviews with management and union officials in over 75 companies between 1964 and 1969, this report analyzes the concept of the internal labor market and describes its relevance for federal manpower policy. The management interviews, which were mostly in personnel, industrial engineering, and operations areas of manufacturing companies, were supplemented by data on the disadvantaged provided by civil rights, poverty, and manpower agencies. The report utilizes the framework established in the study to show that the internal market does not imply inefficiency and may represent an improvement in dealing with structural unemployment. (BH) .4 /.. .118-1`;003 INTERNAL LABOR MARKETS AND MANPOWER ANALYSIS PETER B. DOERINGER Assistant Professor of Economics Harvard University MICHAEL J. PIORE Associate Profe s sor of Economics Massachusetts Institute of Technology ',Jay 1970 This research was preparedunder a contract with the Office of ManpowerResearch, U.S. Departmentof Labor, under the authorityof the Manpower Development and Training Act.Researchers undertakingsuch projects under the Government sponsorshipare encouraged to express their own judgementfreely.Therefore, points of view or opinions stated inthis document do not necessarily represent theofficial position of the Department of Labor. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context.