Modernism and the Classical Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Didactic Fragmentation in ''Scenes from the Big Picture'

Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté To cite this version: Virginie Privas-Bréauté. Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty. 2012. halshs-01071477 HAL Id: halshs-01071477 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01071477 Preprint submitted on 5 Oct 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. !1 Didactic Fragmentation in Scenes from the Big Picture (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Brecht’s dramatic theory helps demonstrate that the contours of contemporary Northern Irish drama have been reshaped. In this respect, Owen McCafferty’s play Scenes from the Big Picture has Neo-Brechtian resonances. The audience is presented with frag- ments of lives of people, bits and pieces of a whole picture. This play exemplifies Brecht’s idea of a didactic play in so far as the audience is called to learn about the Northern Irish Troubles from the play through the device of fragmentation: the uneven background of McCafferty’s play – i.e. the Troubles – is peopled with traumatised indi- viduals, proportionally fragmented. -

The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim

The Theatre of the Real MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb i 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:32:40:32 PPMM MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim G INA MASUCCI MACK ENZIE THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiiiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM Copyright © 2008 by Th e Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKenzie, Gina Masucci. Th e theatre of the real : Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim / Gina Masucci MacKenzie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4 (cd-rom) 1. English drama—Irish authors—History and criticism—Th eory, etc. 2. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 1865–1939—Dramatic works. 3. Beckett, Samuel, 1906–1989—Dramatic works. 4. Sondheim, Stephen—Criticism and interpretation. 5. Th eater—United States—History— 20th century. 6. Th eater—Great Britain—History—20th century. 7. Ireland—Intellectual life—20th century. 8. United States—Intellectual life—20th century. I. Title. PR8789.M35 2008 822.009—dc22 2008024450 Th is book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4) Cover design by Jason Moore. Text design by Jennifer Forsythe. Typeset in Adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Th omson-Shore, Inc. Th e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

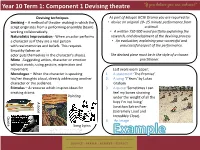

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising theatre Devising techniques As part of Eduqas GCSE Drama you are required to: Devising – A method of theatre- making in which the • devise an original 10- 15 minute performance from script originates from a performing ensemble (team) a stimuli working collaboratively. • A written 750-900 word portfolio explaining the Naturalistic Improvisation - When an actor performs research, and development of the devising process. a character as if they are a real person • An evaluation, explaining your successful and with real memories and beliefs. This requires unsuccessful aspect of the performance. Empathy (when an actor puts themselves in the character’s shoes). The devised piece must be in the style of a chosen Mime -Suggesting action, character or emotion practitioner. without words, using gesture, expression and movement. Last years exam paper: Monologue – When the character is speaking 1. A statement ‘The Promise’ his/her thoughts aloud, directly addressing another 2. A song ‘7 Years’ by Lukas character or the audience. Graham Stimulus – A recourse which inspires ideas for 3. A quote ‘Sometimes I can creating drama. feel my bones straining Painting under the weight of all the A book lives I’m not living’ Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud and Quote Incredibly Close). 4. An Image Song Lyrics Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre Research- Explore each stimuli, finding out all the A sequence in a chronological order fact around it. including a beginning, middle and end. Map ideas – Write all your initial ideas on a mind map. Discuss – Share your ideas with your group and decide on a final idea. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

JULY 2017 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of King Richard II. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. IMPACT Our prominence nationally and locally brings with it a responsibility to listen, collaborate, and act with integrity in order to serve. -

Download PDF Datastream

City of Praise: The Politics of Encomium in Classical Athens By Mitchell H. Parks B.A., Grinnell College, 2008 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Mitchell H. Parks This dissertation by Mitchell H. Parks is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Adele Scafuro, Adviser Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Johanna Hanink, Reader Date Joseph D. Reed, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Mitchell H. Parks was born on February 16, 1987, in Kearney, NE, and spent his childhood and adolescence in Selma, CA, Glenside, PA, and Kearney, MO (sic). In 2004 he began studying at Grinnell College in Grinnell, IA, and in 2007 he spent a semester in Greece through the College Year in Athens program. He received his B.A. in Classics with honors in 2008, at which time he was also inducted into Phi Beta Kappa and was awarded the Grinnell Classics Department’s Seneca Prize. During his graduate work at Brown University in Providence, RI, he delivered papers at the annual meetings of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South (2012) and the American Philological Association (2014), and in the summer of 2011 he taught ancient Greek for the Hellenic Education & Research Center program in Thouria, Greece, in addition to attending the British School at Athens epigraphy course. -

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce's Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL a Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingh

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce’s Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English Studies School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers the imbrications created by James Joyce in his writing with the work of John Milton, through allusions, references and verbal echoes. These imbrications are analysed in light of the concept of ‘presence’, based on theories of intertextuality variously proposed by John Shawcross, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, and Eelco Runia. My analysis also deploys Gumbrecht’s concept of stimmung in order to explain how Joyce incorporates a Miltonic ‘atmosphere’ that pervades and enriches his characters and plot. By using a chronological approach, I show the subtlety of Milton’s presence in Joyce’s writing and Joyce’s strategy of weaving it into the ‘fabric’ of his works, from slight verbal echoes in Joyce’s early collection of poems, Chamber Music, to a culminating mass of Miltonic references and allusions in the multilingual Finnegans Wake. -

Russian Constructivism

De Stijl in the Netherlands Russian Constructivism 26 Constructivism was an artistic and architectural movement that originated in Russia from 1919 onward which rejected the idea of "art for art's sake" in favour of art as a practice directed towards social purposes and uses. Constructivism as an active force lasted until around 1934, having a great deal of effect on developments in the art of the Weimar Republic (post world war one Germany) and elsewhere, before being replaced by Socialist Realism. Its motifs have sporadically recurred in other art movements since. It had a lasting impact on modern design through some of its members becoming involved with the Bauhaus group. Constructivism had a particularly lasting effect on typography and graphic design. Constructivism art refers to the optimistic, non-representational relief construction, sculpture, kinetics and painting. The artists did not believe in abstract ideas, rather they tried to link art with concrete and tangible ideas. Early modern movements around WWI were idealistic, seeking a new order in art and architecture that dealt with social and economic problems. They wanted to renew the idea that the apex of artwork does not revolve around "fine art", but rather emphasized that the most priceless artwork can often be discovered in the nuances of "practical art" and through portraying man and mechanization into one aesthetic program. Constructivism was first created in Russia in 1913 when the Russian sculptor Vladimir Tatlin, during his journey to Paris, discovered the works of Braque and Picasso. When Tatlin was back in Russia, he began producing sculptured out of assemblages, but he abandoned any reference to precise subjects or themes. -

Recordings by Artist

Recordings by Artist Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 10,000 Maniacs MTV Unplugged CD 1993 3Ds The Venus Trail CD 1993 Hellzapoppin CD 1992 808 State 808 Utd. State 90 CD 1989 Adamson, Barry Soul Murder CD 1997 Oedipus Schmoedipus CD 1996 Moss Side Story CD 1988 Afghan Whigs 1965 CD 1998 Honky's Ladder CD 1996 Black Love CD 1996 What Jail Is Like CD 1994 Gentlemen CD 1993 Congregation CD 1992 Air Talkie Walkie CD 2004 Amos, Tori From The Choirgirl Hotel CD 1998 Little Earthquakes CD 1991 Apoptygma Berzerk Harmonizer CD 2002 Welcome To Earth CD 2000 7 CD 1998 Armstrong, Louis Greatest Hits CD 1996 Ash Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 1 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1977 CD 1996 Assemblage 23 Failure CD 2001 Atari Teenage Riot 60 Second Wipe Out CD 1999 Burn, Berlin, Burn! CD 1997 Delete Yourself CD 1995 Ataris, The So Long, Astoria CD 2003 Atomsplit Atonsplit CD 2004 Autolux Future Perfect CD 2004 Avalanches, The Since I left You CD 2001 Babylon Zoo Spaceman CD 1996 Badu, Erykah Mama's Gun CD 2000 Baduizm CD 1997 Bailterspace Solar 3 CD 1998 Capsul CD 1997 Splat CD 1995 Vortura CD 1994 Robot World CD 1993 Bangles, The Greatest Hits CD 1990 Barenaked Ladies Disc One 1991-2001 CD 2001 Maroon CD 2000 Bauhaus The Sky's Gone Out CD 1988 Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 2 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1979-1983: Volume One CD 1986 In The Flat Field CD 1980 Beastie Boys Ill Communication CD 1994 Check Your Head CD 1992 Paul's Boutique CD 1989 Licensed To Ill CD 1986 Beatles, The Sgt -

Futurism's and Dadaism's Popular Mechanics

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D/CI) Spring 2012 Professor Caroline A. Jones Notes History. Theory and Criticism Section. Department of Architecture Lecture 12 NEW SUBJECTS FOR MODERNITY: Lecture 12: Futurism's and Dadaism's Popular Mechanics I. Picasso's exorcism and its import for "peripheral" Europeans: the sign and/or the fetish II. Futurist Programs (Avant-Garde in celebration of war and the state) A. Approaching the Great War: ..... the world's only hygiene" 1 ) the poet Marinetti in Ie Figaro, Paris, 20 February 1909 2) the poet D'Annunzio's flights over Trieste (winter 1915-16), expanding to Vienna (1918-19) - propaganda as cultural war 3) Italian Irredentism, "parole in Liberta," and fascist modernism B. Speed, dynamism, and simultaneity 1) The visual culture of technology's impact on the body 2) The futurist fetish: the externally hardened and artificially stabilized body, enhanced by its "other" III. Dadas at large (Avant-Garde in critique of war and the state) A. Cosmopolitan cities, the Avant-Garde in exile, and the anti-commodity fetish 1) Zurich, Berlin, New York, Hannover, Barcelona ... 2) The dadaist fetish: prosthetics and eroticism, a destabilized body B. Tactics - Performance, journalislTI, art objects, exhibition events, montage, politics 1) Performance (1916-19, Ball, Tzara) 2) From collage to montage (1919-40s, Hausmann, Hoch, Heartfield) 3) "Dada Messe" (1920) - Int'I Dada Fair, a new kind of market? 4) Dada environment in exile (1920s-40s, Schwitters' Merzbau) Images (selected) for Lecture 14 unspecified medium=oil on canvas Futurism Carlo Carra, Absinthe Drinker. 1911 Carra. 10lts of a Cab, 1911 Carra, Interventionist Demonstration 1914 (collage) Filippo Tomasso Marinetti, "A Tumultuous Assembly," Les mots en liberte futuristes, 1919 (poem) Marinetti Parole in Liberta, 1932 (poem) Giacomo Balla. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/79208 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-24 and may be subject to change. 0821-07_Babesch_83_13 23-09-2008 16:15 Pagina 187 BABESCH 83 (2008), 187-222. doi: 10.2143/BAB.83.0.2033107. Reviews KAREN FRANCIS, Explorations in Albania, 1930-39. ing his brief campaign in 1939, which focused on the The Notebooks of Luigi Cardini, Prehistorian with the area around Butrint, Cardini recalls the discovery of ‘a Italian Archaeological Mission. London: British School vast Palaeolithic surface deposit’, at Xarra; a complex of five adjacent caves ‘with abundant remains of an at Athens, 2005. X+222 pp., 99 figs.; 30 cm (Sup- Eneolithic culture’, near Himara; and preliminary in- plementary volume 37). – ISBN 0-904887-480. vestigations at the caves of Shën Marina and Gorandzi. Around the village of Xarra, Cardini collected hundreds The publication of notebooks belonging to Luigi Car- of flint tools including Middle and Upper Palaeolithic dini (1898-1971), recording his work with the Italian finds that proved the existence of an early open-air site, Archaeological Mission to Albania between 1930 and the first of its kind to be discovered in the Balkans. Trial 1939, sheds new light on the prehistory of Albania, and trenches at the Himara caves yielded Eneolithic pottery provides a fascinating portrait of archaeological inves- and numerous flakes of flint and jasper, and at Shën tigation. -

1914 the Avant-Gardes at War 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2014

1914 The Avant-Gardes at War 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2014 Media Conference: 7 November 2013, 11 a.m. Content 1. Exhibition Dates Page 2 2. Information on the Exhibition Page 4 3. Wall Quotations Page 6 4. List of Artists Page 11 5. Catalogue Page 13 6. Current and Upcoming Exhibitions Page 14 Head of Corporate Communications/Press Officer Sven Bergmann T +49 228 9171–204 F +49 228 9171–211 [email protected] Exhibition Dates Duration 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2013 Director Rein Wolfs Managing Director Dr. Bernhard Spies Curator Prof. Dr. Uwe M. Schneede Exhibition Manager Dr. Angelica C. Francke Dr. Wolfger Stumpfe Head of Corporate Communications/ Sven Bergmann Press Officer Catalogue / Press Copy € 39 / € 20 Opening Hours Tuesday and Wednesday: 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Public Holidays: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Closed on Mondays Admission 1914 and Missing Sons standard / reduced / family ticket € 10 / € 6.50 / € 16 Happy Hour-Ticket € 6 Tuesday and Wednesday: 7 to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 5 to 7 p.m. (for individuals only) Advance Ticket Sales standard / reduced / family ticket € 11.90 / € 7.90 / € 19.90 inclusive public transport ticket (VRS) on www.bonnticket.de ticket hotline: T +49 228 502010 Admission for all exhibitions standard / reduced / family ticket € 16/ € 11 / € 26.50 Audio Guide for adults € 4 / reduced € 3 in German language only Guided Tours in different languages English, Dutch, French and other languages on request Guided Group Tours information T +49 228 9171–243 and registration F +49 228 9171–244 [email protected] (ever both exhibitions: 1914 and Missing Sons) Public Transport Underground lines 16, 63, 66 and bus lines 610, 611 and 630 to Heussallee / Museumsmeile. -

Rage in Eden Records, Po Box 17, 78-210 Bialogard 2, Poland [email protected]

RAGE IN EDEN RECORDS, PO BOX 17, 78-210 BIALOGARD 2, POLAND [email protected], WWW.RAGEINEDEN.ORG Artist Title Label HAUSCHKA ROOM TO EXPAND 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX BLUE NOTEBOOKS, THE 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX SONGS FROM BEFORE 130701/FAT CAT CD ASCENSION OF THE WAT NUMINOSUM 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY COVER UP 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS LTD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE BLOOD 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE DUB YA 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD PRONG POWER OF THE DAMAGER 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKED AND LOADED 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKTAIL MIXXX 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD BERNOCCHI, ERALDO/FE MANUAL 21ST RECORDS CD BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FA BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FAMILY 21ST RECORDS CD FLOWERS OF NOW INTUITIVE MUSIC LIVE IN COLOGNE 21ST RECORDS CD LOST SIGNAL EVISCERATE 23DB RECORDS CD SEVENDUST ALPHA 7 BROS RECORDS CD SEVENDUST CHAPTER VII: HOPE & SORROW 7 BROS RECORDS CD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM COLD A DIFFERENT DRUM MCD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM ON THE ROAD TO WISDOM A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE ALTERNATES AND REMIXES A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE EVENING BELL, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE FALLING STAR, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE MACHINE BOX A DIFFERENT DRUM BOX BLUE OCTOBER ONE DAY SILVER, ONE DAY GOLD A DIFFERENT DRUM CD BLUE OCTOBER UK INCOMING 10th A DIFFERENT DRUM 2CD CAPSIZE A PERFECT WRECK A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMIC ALLY TWIN SUN A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMICITY ESCAPE POD FOR TWO A DIFFERENT DRUM CD DIGNITY