New Directions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oi Duck-Billed Platypus! This July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018

JULY 2019 EDITION Featuring buyer’s recommends and new titles in books, DVD & Blu-ray Cats sit on gnats, dogs sit on logs, and duck-billed platypuses sit on …? Find out in the hilarious Oi Duck-billed Platypus! this July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018. Illustrations © Jim Field, 2018. Gray, © Kes Text NEW for 2019 Oi Duck-billed Platypus! 9781444937336 PB | £6.99 Platypus Sales Brochure Cover v5.indd 1 19/03/2019 09:31 P. 11 Adult Titles P. 133 Children’s Titles P. 180 Entertainment Releases THIS PUBLICATION IS ALSO AVAILABLE DIGITALLY VIA OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.GARDNERS.COM “You need to read this book, Smarty’s a legend” Arthur Smith A Hitch in Time Andy Smart Andy Smart’s early adventures are a series of jaw-dropping ISBN: 978-0-7495-8189-3 feats and bizarre situations from RRP: £9.99 which, amazingly, he emerged Format: PB Pub date: 25 July 2019 unscathed. WELCOME JULY 2019 3 FRONT COVER Oi Duck-billed Platypus! by Kes Gray Age 1 to 5. A brilliantly funny, rhyming read-aloud picture book - jam-packed with animals and silliness, from the bestselling, multi-award-winning creators of ‘Oi Frog!’ Oi! Where are duck-billed platypuses meant to sit? And kookaburras and hippopotamuses and all the other animals with impossible-to-rhyme- with names... Over to you Frog! The laughter never ends with Oi Frog and Friends. Illustrated by Jim Field. 9781444937336 | Hachette Children’s | PB | £6.99 GARDNERS PUBLICATIONS ALSO INSIDE PAGE 4 Buyer’s Recommends PAGE 8 Recall List PAGE 11 Gardners Independent Booksellers Affiliate July Adult’s Key New Titles Programme publication includes a monthly selection of titles chosen specifically for PAGE 115 independent booksellers by our affiliate July Adult’s New Titles publishers. -

Fudge the Elf

1 Fudge The Elf Ken Reid The Laura Maguire collection Published October 2019 All Rights Reserved Sometime in the late nineteen nineties, my daughter Laura, started collecting Fudge books, the creation of the highly individual Ken Reid. The books, the daily strip in 'The Manchester Evening News, had been a part of my childhood. Laura and her brother Adam avidly read the few dog eared volumes I had managed to retain over the years. In 2004 I created a 'Fudge The Elf' website. This brought in many contacts, collectors, individuals trying to find copies of the books, Ken's Son, the illustrator and colourist John Ridgeway, et al. For various reasons I have decided to take the existing website off-line. The PDF faithfully reflects the entire contents of the original website. Should you wish to get in touch with me: [email protected] Best Regards, Peter Maguire, Brussels 2019 2 CONTENTS 4. Ken Reid (1919–1987) 5. Why This Website - Introduction 2004 6. Adventures of Fudge 8. Frolics With Fudge 10. Fudge's Trip To The Moon 12. Fudge And The Dragon 14. Fudge In Bubbleville 16. Fudge In Toffee Town 18. Fudge Turns Detective Savoy Books Editions 20. Fudge And The Dragon 22. Fudge In Bubbleville The Brockhampton Press Ltd 24. The Adventures Of Dilly Duckling Collectors 25. Arthur Gilbert 35. Peter Hansen 36. Anne Wilikinson 37. Les Speakman Colourist And Illustrator 38. John Ridgeway Appendix 39. Ken Reid-The Comic Genius 3 Ken Reid (1919–1987) Ken Reid enjoyed a career as a children's illustrator for more than forty years. -

Download the Catalogue

Five Hundred Years of Fine, Fancy and Frivolous Bindings George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK Tel: 01225 466000 • Fax: 01225 482122 Email: [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com BOUND BY BROCA 1. AINSWORTH (William Harrison). The Miser's Daughter: A Tale. 20 engraved plates by George Cruikshank. First Edition. Three volumes. 8vo. [198 x 120 x 66 mm]. vii, [i], 296 pp; iv, 291 pp; iv, 311 pp. Bound c.1900 by L. Broca (signed on the front endleaves) in half red goatskin, marbled paper sides, the spines divided into six panels with gilt compartments, lettered in the second and third and dated at the foot, the others tooled with a rose and leaves on a dotted background, marbled endleaves, top edges gilt. (The paper sides slightly rubbed). [ebc2209]. London: [by T. C. Savill for] Cunningham and Mortimer, 1842. £750 A fine copy in a very handsome binding. Lucien Broca was a Frenchman who came to London to work for Antoine Chatelin, and from 1876 to 1889 he was in partnership with Simon Kaufmann. From 1890 he appears under his own name in Shaftesbury Avenue, and in 1901 he was at Percy Street, calling himself an "Art Binder". He was recognised as a superb trade finisher, and Marianne Tidcombe has confirmed that he actually executed most of Sarah Prideaux's bindings from the mid-1890s. Circular leather bookplate of Alexander Lawson Duncan of Jordanstone House, Perthshire. STENCILLED CALF 2. AKENSIDE (Mark). The Poems. Fine mezzotint frontispiece portrait by Fisher after Pond. First Collected Edition. 4to. [300 x 240 x 42 mm]. -

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

University of Warwick Institutional Repository

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36101 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. PARENTAL PARTICIPATION IN PRIMARY EDUCATION. Carol. Vincent. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations University of Warwick. April 1993. -1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements List of abbreviations Summary CHAPTER ONE Parents, Power and Participation: Some Themes 1 The nature of the state education system 2 Power and participation 5 Theorising 'the community' 13 Social democratic ideals: community education 17 Conclusion 23 CHAPTER TWO The Role of 'The Parent' in State Education ' 27 Social democracy and the state education system 27 The rise of the New Right 34 The New Right's education project - the parent as consumer 37 Conclusion 44 CHAPTER THREE Parent Participation in Primary Education: The Present Day 48 Problematizing home-school relationships 48 Parental roles 55 - The supporter-learner model 55 - Parents as consumers: The Parents' Charter 63 - Independent parents 65 - Parents as participants 66 Conclusion 68 CHAPTER FOUR Researching Home-School Relations 71 Case study research - a brief discussion 71 The design of -

School-Age NOTES. 1996. REPORT NO ISSN-0278-3126 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 98P.; for Volume 14, See ED 382 331; Volume 15, See PS 023 974

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 402 083 PS 024 861 AUTHOR Scofield, Richard T., Ed. TITLE School-Age NOTES. 1996. REPORT NO ISSN-0278-3126 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 98p.; For volume 14, see ED 382 331; volume 15, see PS 023 974. AVAILABLE FROMSchool Age NOTES, P.O. Box 40205, Nashville, TN 37204; phone: 615-242-8464; fax: 615-242-8260 (1 year, 12-issue subscription, $22.95). PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT School-Age Notes; v16 n5 Sep 1995-Aug 1996 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *After School Programs; Caregiver Child Relationship; Child Caregivers; *Conflict Resolution; Curriculum Development; Discipline; Elementary Education; Elementary School Students; Enrichment Activities; Newsletters; *School Age Day Care IDENTIFIERS Developmentally Appropriate Programs; *Tennessee ABSTRACT These 12 newsletter issues provide support and information for providers of child care for school-age children. The featured articles for each month are: (1)"To Be a Caregiver Again"; (2) "When To Talk to Parents";(3) "NSACA (National School-Age Care Alliance) Launches Accreditation Pilot";(4) "A New Way of Thinking about the Middle School 'Program"; (5) "Celebrating Exuberance: Is It Wildness or Is It Exuberance?" (6)"A Middle School After-School Philosophy";(7) "Freeing Children from Labels";(8) "Cities Concerned about Child Care and School Age Care";(9) "Encouraging Cross Gender Play";(10) "City of Tucson Proves Committed to SAC (School Age Care)";(11) "Rethinking Summer"; and (12) "Accreditation for School-Age Programs--Now." (WJC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** Volume XVI The Newsletter for School-Age Care Professions lat 1995'96 en O00 OC1 IC) U.S. -

Treaty Advances Make the Slam Without the Diamond ► Pass 2 ♦ Pass Played a Diamond, but West Showed 1986 CHEW CEL$Prrry SEDAN ► Pass 3 NT Out

24—MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday, June 1, 1990 I CARS CARS MOTORCYCLES/ Astrograph FOR SALE MOTORCYCLES/ L ^ FOR SALE [2 2 J MOPEDS MOPEDS where you can't make a move until BLUE TEAAPO-1987. Air DODGE - 1986. ‘150’, 318 KAWAKSAKI-1988 KX the finger of blame at them. someone upon whom you're depending conditioning, 50K. CID, autamatic, bed 250. Runs gaad. $1850ar ^ o u r does. Your wail might be in vain. CAPRICORN (Dec. 22-Jan. 19) Several Good condition. Runs liner, faal bax, 50K, Motorcycle Insurance best otter. LEO (July 23-Aug. 22) Be extremely goals that are of importance to you to well. $4,900. Coll 643- $5500. 742-8669. Many com^ve companies J birthday careful in your conversations today that day might not be of equal significance 9382. ______________ to persons with whom you'll be in Call Fa Free Quote you do not put someone down in order CADILLAC-1979 Coupe to make yourself look good. It could volved. This could cause everyone to Automobile Associates WANTED TO pull in a different direction. DeVllle. New point, raTRUCKS/VANS June 2,1990 have the opposite affect of what you Cleon, runs greot. Must ofVemon BUY/TRADE desire. AQUARIUS (Jan. 20-Feb. 19) It’s best sell. $3,200 or best otter. FOR SALE fi7A.09i;A Any character building situations to VIRGO (Aug. 23-Sept. 22) In your com not to make any promises today that 635-7391. which you're exposed in the year ahead, mercial dealings today, be open and you're not absolutely certain you can FORD-1984 Van. -

TRAVELS in the MINISTRY in Canadian Yearly Meeting

TRAVELS IN THE MINISTRY in Canadian Yearly Meeting JANUARY 10, 2004 - FEBRUARY 11, 2006 JOURNALS By Margaret Slavin CONTENTS Page Ontario Starting out 1 Yonge Street Monthly Meeting. 5 Simcoe-Muskoka Monthly Meeting at Orillia Worship Group 9 Guelph Worship Group 13 Kitchener Monthly Meeting 18 Lucknow Worship Group 22 Coldstream Monthly Meeting 28 YarmouthMonthlyMeeting 32 Pelham Executive Meeting 37 Peterborough Allowed Meeting 42 Wooler Monthly Meeting 49 Manitoba Winnipeg Worship Group (now: Allowed Meeting) 55 Alberta Edmonton Monthly Meeting 60 British Columbia Saanich Peninsula Monthly Meeting 67 Vancouver Monthly Meeting 73 Western Half-Yearly Meeting, etc. 79 Vernon Monthly Meeting, Argenta Monthly Meeting 84 Saskatchewan Regina Allowed Meeting 88 Quebec Montreal Monthly Meeting, Laurentian Worship Group 94 Saskatchewan Saskatoon Allowed Meeting 103 New Brunswick Canadian Yearly Meeting and unwinding in Fredericton 106 Hampton Worship Group 108 Fundy Friends Worship Group 113 Contents ii Nova Scotia Atlantic Friends and friends: Bedford, Dartmouth, Baie Verte, Scotsburn 118 Wolfville Monthly Meeting 124 New Brunswick Sackville Worship Group & New England / Atlantic Friends Gathering 129 Nova Scotia Halifax Friends Meeting & South Shore Worship Group 133 Ontario Thunder Bay Worship Group 141 British Columbia Visiting isolated Friends of South Kootenay Worship Group 146 Steveston, Coquitlam, North Burnaby Worship Groups 151 Visiting isolated Friends in Powell River (now a worship group) 157 North Island Worship Group CLVII Mid-Island Allowed Meeting 160 Alberta Calgary Monthly Meeting 163 Ontario Simcoe-Muskoka return visit Sr Grey Bruce Worship Group 169 Hamilton Monthly Meeting 174 Toronto Monthly Meeting 177 Thousand Islands Monthly Meeting 183 New Brunswick Fredericton Worship Group 187 Prince Edward Island P.E.I. -

Bologna 2019 Children

FRONTLIST BOLOGNA 2019 CHILDREN bayard FOREIGN RIGHTS Table of contents TODDLERS ACTIVITES PICTURE BOOKS RELIGION Discover the world 3-5 Preschool 3-5 Preschool 3-6 Preschool Fleurs / Formes – Tullet Je fais des gâteaux moi-même Monsieur Lion s’habille Je prie de tout mon corps Mon premiers imagier – la maison Le livre avec un trou - Tullet Les Larmes En chemin avec Jésus Mes tout premiers docs Cahier de coloriages - Tullet L’étoile de Robin Le bon berger Mes albums Montessori L’imaginier - Tullet 8-12 Middle grade Mes animaux tout doux du jardin Des trous dans le vent La bible – Grands récits et Livres gigognes : les émotions Bienvenue à Filouville NON-FICTION personnages Bravo les petits doigts ! 3-5 Preschool First stories Mon grand imagier des odeurs Badaboom Patatra coffret Mes docs en forme FICTION Cap de nous faire rire ? Mes petits rituels: attention 5-8 Early readers Cache-cache cocotte Anim’passion: les trains La mythologie grecque en cent Ronron et fripon 5-8 Early readers épisodes - Le feuilleton d’Artémis Activities Anim’action: La terre 8-12 Middle grade Relax sessions Savane secrète Eloi et Dagobert Yoga des petits Mon atlas animé du ciel et de Enquête à la montagne l’espace Tourne roulette Des vacances bien pourries Questions des petits sur les parents Les livres sonores à caresser John et le royaume d’en bas Le petit livre pour parler des familles Les Quinzebilles Mes cahiers pour bien grandir Super victime de l’injustice 8-12 Middle grade Les romans ateliers : Un été de Stop aux violences sexuelles faites gourmandise, d’amour et de vie aux enfants Maléfice sur Rome L’égalité filles-Garçons 12+ Young adults On se dit tout entre filles Acid Summer Les docs BD – Apollo 11 Mission Lune TODDLERS Fleurs ! Hervé Tullet’s latest creation specially designed for babies. -

A Selection of French Titles

A SELECTIONSELECTION OFOF FRENCHFRENCH TITLESTITLES CCHILDHILDREEN’SN’S BBOOKSOOKS 22020020 Promoting French publishing around the world For nearly 150 years, BIEF has been promoting French publishers’ creations on the international scene with the vocation of facilitating and developing exchanges between French and foreign professionals in the publishing industry. This catalogue presents 31 publishing houses and 155 titles. It is intended as both a working and reference tool for all those interested in children’s books published in France, especially foreign publishers, booksellers and librarians keen to build their list of translated and/or adapted works in this sector. This catalogue was created to promote the discovery of the great variety in and the high quality of children’s publishing in France, to help publishers, booksellers and librarians strengthen existing ties with their French counterparts. Cover illustration: © Où va le chat ?, By Léa Decan, Éditions L’Agrume, 2020 Index of publishers / Children’s Books 4 Actes Sud Junior 7 L’Agrume 10 Albin Michel Jeunesse 13 Groupe Bayard 16 Casterman 19 Didier Jeunesse 22 L’école des loisirs 25 Éditions Animées 28 Les Éditions des Éléphants 31 Flammarion Jeunesse – Père Castor 34 Gallimard Jeunesse 37 Glénat Jeunesse 40 Les Éditions de la Gouttière 43 Les Grandes Personnes 46 Grasset Jeunesse 49 Hachette Jeunesse 52 Hatier Jeunesse 55 Hélium 58 Joyvox 61 Kilowatt 64 Little Urban 67 Mediatoon – Ankama/Dargaud/Dupuis/Le Lombard 70 Michel Lafon 73 Nathan 76 Éditions du Ricochet 79 Rouergue -

Franklin, Manville, Millstone Join 16Th Seniors' Dilemma

Vol. 36, No. 14 Thursday, April 4, 1991 50* Franklin, Seniors' Manville, dilemma: \/J Millstone Where join 16th to meet? Pass the paata By Peter ZlrnKe By Laurie Lynn Strasser The Packet Group Staff Writer 1W Hagimtan $um Real© Under the new legislative re- The Franklin Township Council ration Coaynlftte win fcoet Its districting plan approved by the New has been negotiating with the Board fint awing .pasjt dinner from Jersey Apportionment Commission of Education to continue providing a 5*30 p.m. ftiSky, April 5. March 28, Manville, Millstone and meeting place for the Franklin Park Small intimate tablet covered Franklin will be in the same district as Senior Citizens Club, sponsored by w«6 ted checked table cloth*, most of the rest of Somerset County. the municipal recreation department. candlelight and teal dial** make Formerly, they were part of the But members of the Franklin "Tntioria. Hageman" a place 14th District, which extended north Township Senior Citizens Inc. — a worth ftavteg dinner, event or- from South Brunswick to include the larger, private club — would prefer gaftiun claim. Strolling nuui- Somerset communities of Manville, that the township instead consider citjw *djl io the, Victorian farm- Franklin, Rocky Hill and Millstone. establishing a new facility at the other hofc* a«*fc* ' Under the plan, drawn to reflect side of town, nearer to where they population shifts that occurred over live. •alSiaitaliinCttd.foUpwod the past decade, they are part of the "We feel it should be built at the 1 by * Choice of two .{ptas, new 16th District, which encom- municipal complex, ' said Thomas mitoafjof meat «auce, uniage passes all of Somerset County, except Kuhn, vice president of the Franklin North Plainfield, Bound Brook. -

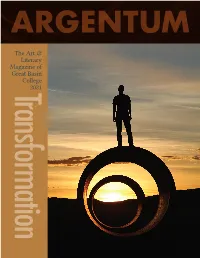

2021 Argentum Co-Editors

ARGENTUM The Art & Literary Magazine of Great Basin College 2021 Transformation Pinecone Eggs Medium: Pinecones and Resin Tim Terras Thoughts on the 2021 Issue The one constant in this year of the pandemic was change. We thank the contributors who embraced these changes and transformed their experiences into art. Special thanks are also extended to Angie de Braga, Dr. Josh Webster, Jennifer Bean, and Frank Sawyer for helping to bring this issue to fruition. This year’s edition features audio recordings of selected pieces, thanks to the efforts of John Patrick Rice, Ph.D. We are pleased to showcase the voice talents of Scott Glennon, Kate Rhoswen, and John Patrick Rice, with sound design by Dawn Bartlett. We hope you enjoy this year’s publication, and consider submitting to the 2022 issue. Our website is www.gbcnv.edu/argentum and staff can be emailed at [email protected]. Jennifer Stieger and Dori Andrepont 2020–2021 Argentum Co-Editors FRONT COVER Sun Tunnel Sunset Medium: Photography Kim Otheim Table of Contents Outside Front Cover Argentum Selection Committee . 2 Sun Tunnel Sunset Blue Skies in a Valley of Fire by Angela Hagfeldt . 3 Kim Otheim Wings of a Different Color by Shania Brown . 4 Inside Front Cover The Hunger by Rani Clark . 5 Pinecone Eggs Evisceration by Richard A . Sanchez . 7 Tim Terras Sky, Sea and Tradition by Erika Martinez . 8 Of Tequila and Coffee by Ariana Stadtlander . 9 Inside Back Cover Winter Transformation My Angel of Music by Jacqueline C . Bertot . 14 Angie de Braga Tolstoy's Transformation by Simone Marie .