TRANSLATABILITY of the AESTHETIC ASPECT of RHYTHM in QUR’ANIC VERSES Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And How to Convert to Islam in the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious

What is Islam? and How to Convert to Islam In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful All Praise be to Allah, the Lord of the Worlds and may peace and blessings of Allah be upon the most honorable of all Prophets and Messengers; Muhammad. Introduction Every right or wrong ideology, every beneficial or harmful community association and every good or evil party has principles, intellectual basis and ideological issues that determine its purpose and direction and become as a constitution for its members and followers. Whoever wants to belong to one of them, has to look firstly at its principles. If he is satisfied with the principles, believes of its validity and accepts it with his conscious and subconscious mind without any doubts, then he can be a member of that association or party. Afterwards, he enrolls among the lines of its members and has to perform the duties required by the constitution and pay the membership fees that are set by the laws. He also has to exhibit behaviors indicate loyalty to its principles besides always remembering those principles to not commit deeds contradict with them. He has to be a perfect example via showing decent morals and behaviors and become a real proponent of them. Nutshell, being a member of a party or association requires: knowing its laws, believing in itsprinciples, obeying its rules and conducing one’s life accordance to it.This is a general situation that also applies to Islam. Therefore, whoever wants to enter Islam has to firstly accept its rational bases and assertively believe in them in order to have strong doctrine or faith. -

An Analysis of Taqwa in the Holy Quran: Surah Al- Baqarah

IJASOS- International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, Vol. III, Issue 8, August 2017 AN ANALYSIS OF TAQWA IN THE HOLY QURAN: SURAH AL- BAQARAH Harison Mohd. Sidek1*, Sulaiman Ismail2, Noor Saazai Mat Said3, Fariza Puteh Behak4, Hazleena Baharun5, Sulhah Ramli6, Mohd Aizuddin Abd Aziz7, Noor Azizi Ismail8, Suraini Mat Ali9 1Associate Professor Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 2Mr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 3Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 4 Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 5 Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 6 Ms., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 7 Mr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 8Associate Professor Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 9Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract Within the context of the Islamic religion, having Taqwa or the traits of righteousness is imperative because Taqwa reflects the level of a Muslim’s faith. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to identify the traits of Takwa in surah Al-Baqara in the Holy Quran. The data for this study were obtained from verses in surah Al-Baqara. Purposive sampling was used to select the verses that contain the traits of Taqwa using an established tafseer (Quranic interpretation) in the Qurainic field as a guideline in marking the Taqwa traits in sampling the verses. Two experts in the field of Quranic tafseer validated the traits of Taqwa extracted from each selected verse. -

Surah & Verses Facts

Surah & Verses Facts Verses Recited: 1 - al-Faatihah – ‘The Opening’, 2 - Baqarah – ‘The Cow’ (Verses 1-141) Objective: Al-Baqarah’s main objective is the succession of man on earth. To put it simply, it calls upon us, “You Muslims are responsible for earth”. Other Facts: Al-Baqarah is the first surah to be revealed in Al-Madinah after the Prophet’s emigration - Surat Al-Baqara is the longest surah in the Qur’an comprising of 286 ayahs Surah 1 - al-Faatihah –‘ The Opening Summary: It is named al-Faatihah, the Opening - because it opens the Book and by it the recitation in prayer commences. It is also named Ummul Qur`aan, the Mother of the Qur`aan, and Ummul Kitaab, the Mother of the Book. In essence it is the supplication to which what follows from the Quran is the response. Surah 2 - Baqarah –‘The Cow’ Summary: This is the longest Surah of the Quran, and in it occurs the longest verse (2:282). The name of the Surah is from the Parable of the Cow (2:67-71), which illustrates the insufficiency of quarrelsome obedience. When faith is lost, people put off obedience with various excuses; even when at last they obey in the letter, they fail in the spirit and this prevents them from seeing that spiritually they are not alive but dead. For life is movement, activity, striving, fighting against baser things. And this is the burden of the Surah. Verses Description The surah begins by classifying men into three broad categories, depending on how they receive God’s 2:1-29 message 2:30-39 The story of the creation of man, the high destiny intended for him, his fall, and the hope held out to him The story of the children of Israel is told according to their own traditions – what privileges they received and 2:40-86 how they abused them thus illustrating again as a parable the general story of man. -

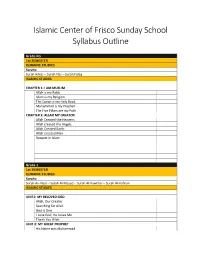

Islamic Center of Frisco Sunday School Syllabus Outline

Islamic Center of Frisco Sunday School Syllabus Outline Grade KG 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah Ikhlas – Surah Nas – Surah Falaq ISLAMIC STUDIES CHAPTER 1: I AM MUSLIM Allah is my Rabb Islam is my Religion The Quran is my Holy Book Muhammad is my Prophet The Five Pillars are my Path CHAPTER 2: ALLAH MY CREATOR Allah Created the Heavens Allah created the Angels Allah Created Earth Allah Created Man Respect in Islam Grade 1 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah An-Nasr – Surah Al-Masad - Surah Al-Kawthar – Surah Al-Kafirun ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIT1: MY BELOVED GOD Allah, Our Creator Searching for Allah God is One I Love God, He Loves Me Thank You Allah UNIT 2: MY GREAT PROPHET His Name was Muhammad Muhammad as a Child Muhammad Worked Hard The Prophet’s Family Muhammad Becomes a Prophet Sahaba: Friends of the Prophet UNIT 3: WORSHIPPING ALLAH Arkan-ul-Islam: The Five Pillars of Islam I Love Salah Wud’oo Makes me Clean Zaid Learns How to Pray UNIT 4: MY MUSLIM WORLD My Muslim Brothers and Sisters Assalam o Alaikum Eid Mubarak UNIT 5: MY MUSLIM MANNERS Allah Loves Kindness Ithaar and Caring I Obey my Parents I am a Muslim, I must be Clean A Dinner in our Neighbor’s Home Leena and Zaid Sleep Over at their Grandparents’ Home Grade 2 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah Al-Quraish – Surah Al-Maun - Surah Al-Humaza – Surah Al-Feel ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIT1: IMAN IN MY LIFE I Think of Allah First I Obey Allah: The Story of Prophet Adam (A.S) The Sons of Adam I Trust Allah: The Story of Prophet Nuh (A.S) My God is My Creator Taqwa: -

Qur'an Translation with Footnotes By

ﺍﻟ ﻘﹸ ﺮﺁﻥﹸ ﺍﻟ ﻜﹶ ﺮﹺ ﻳ ﻢ THE QURÕN English Meanings English Revised and Edited by êaúeeú International All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without written permission from the publisher. © ABUL-QASIM PUBLISHING HOUSE, 1997 AL-MUNTADA AL-ISLAMI, 2004 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data Translation of the Meaning of the Qur’an Translated by Saheeh International – Jeddah 712 pp., 10 x 12 cm. 1 – Quran – Translation 221.4 dc 2737/17 Legal Deposit no. 2737/17 ISBN: 9960-792-63-3 Al-Muntada Al-Islami London + (44) (0) 20-7736-9060 fax: + (44) (0) 20-7736-4255 USA + (608) 277-1855 fax: + (608) 277-0323 Saudi Arabia + (966) (1) 464-1222 fax: + (966) (1) 464-1446 [email protected] THIS BOOK HAS BEEN PRODUCED IN COLLABORATION WITH êAîEEî INTERNATIONAL Professional Editing and Typesetting of Islamic Literature TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................... i Foreword............................................................................................. v History of QurÕŒn Compilation.......................................................viii Merits of Particular S´rahs and Verses............................................. x 1 S´rah al-FŒtiúah ........................................................................... 1 2 S´rah al-Baqarah ......................................................................... -

Tafseer Surah Al-Fil Notes on Nouman Ali Khan’S Concise Commentary of the Quran

(اﻟﻔﯿﻞ) Tafseer Surah al-Fil Notes on Nouman Ali Khan’s Concise Commentary of the Quran By Rameez Abid Introduction ● This surah is in reference to the story of Abraha, who was a Christian military leader and part of the Roman empire, and it took place before the birth of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). He built a huge church and wanted the Arabs to venerate it instead of the Ka’ba. He also wanted to do this for financial reasons because due to the Ka’ba, Mecca was a center for business and he wanted to shift the financial attention to his own region in Yemen ○ Some Arabs went to his new church and defecated in it to insult him for trying to take attention away from the Ka’ba. Abraha was furious and decided to take an army of 60,000, which would consist of elephants as well, to Mecca to destroy the Ka’ba in vengeance ■ However, when he got close to the Ka’ba with his army, Allah destroyed them by sending birds who pelted them with stones ○ Some suggest this was the year in which the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) was born ● Some of the companions viewed this surah and the one after it (Surah al-Quraysh) as one surah. They would not put Basmallah between them for that reason ○ They both need to be understood together because they complement each other and are connected ■ This surah discusses the security of Mecca and Surah al-Quraysh discusses its prosperity. For any society to prosper, it needs both of these things ○ We need to understand that the safety and prosperity of Mecca was due to the supplication of Ibrahim (pbuh), which he made when he was building the Ka’ba with his son Ismaeel (pbuh) ■ He had asked Allah to make Mecca safe and fill it with all kinds of fruit because it was a barren desert without life. -

The Meaning and Characteristics of Islam in the Qur'an

International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, Vol. 24, Issue . 01, 2020 ISSN: 1475 – 7192. The Meaning And Characteristics Of Islam In The Qur'an Baharuddin Husin1, Supriyatin, SY2, Zaimudin3, Imron Zabidi4 Abstract--- Islam contain the meaning of submissiveness and total surrender to Allah SWT and to all His rules that have been revealed to His chosen Prophet, Muhammad (PBUH). Islam is a religion of nature, because Islam is something that is inherent in human beings and has been brought from birth through the nature of Allah’s creation, means that humans from the beginning have a religious instinct of monotheism (tawheed). Islam in accordance with its characteristics, is like a perfect building with a strong foundation of faith and pillar joints in the form of worship to Allah SWT and beautified with noble morals. While the regulations in the Shari'ah function to strengthen the building. While true da'wah and jihad are the fences which guard against the damage done by the enemies of Islam. Islam pays attention to worldly and ukhrawi balance. Islam describes a wholeness and unity in all aspects. Paying attention to peace, optimism in achieving happiness in life, managing personal life, family, society, country and the world as a whole. Set all the creations of Allah SWT in this nature to return to His law. Islam is the eternal religion of Allah SWT that was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). All previous celestial teachings are the unity of the divine teaching in various forms which are constantly updated in accordance with the development of the times, the world, humans, and the demands of preaching at that time. -

ONLINE JIHADIST PROPAGANDA 2019 in Review

ONLINE JIHADIST PROPAGANDA 2019 in review Public release Contents 1. Key findings ............................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 3. Islamic State (IS): striving for post-state relevance .................................................. 6 3.1. Loss of territory in Syria leads to demonstration of force in peripheries ............... 6 3.2. IS falls back on guerrilla tactics ................................................................................ 9 3.3. IS synchronises its media campaigns to demonstrate an esprit de corps ............. 11 3.4. IS supporters emphasize the role of women and children ................................... 14 3.5. IS struggles to keep its footing online ................................................................... 15 4. Al-Qaeda (AQ): a network of local militancy and focused incrementalism ............ 18 4.1. Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) ......................................................... 20 4.2. Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen (al-Shabab) ...................................................... 22 4.3. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) ............................................................. 23 5. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) extends its authority over Idlib .................................. 27 6. Running themes across jihadi groups .................................................................... -

Analyzing the Lexical Relation in Holy Quran English Translation of Surah Mary by Abdullah Yusuf Ali

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Repository of UIN Ar-Raniry Banda Aceh ANALYZING THE LEXICAL RELATION IN HOLY QURAN ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF SURAH MARY BY ABDULLAH YUSUF ALI THESIS Submitted by : HAYATUN SABRIANA Reg. No. 140203008 DEPARTEMENT OF ENGLISH EDUCATION FACULTY OF TARBIYAH AND TEACHER TRAINING ISLAMIC STATE UNIVERSITY OF AR-RANIRY 2018 / 1439 H ACKNOWLEDGEMENT All praise to be Allah, the Almighty, Who has given me the health and oppoertunity to write and to finish this thesis. Peace and salutation be upon to our prophet Muhammad S.A.W, who has brought human beings from the darkness to the lightness I would like to express my gratitude amd high appreciation to my beloved Mama and my other family members, for their loves, patience, attention and support. Also, My sincere gratitude to the supervisors ; Dr. Phil. Saiful Akmal, S.Pd.I, MA and Azizah S.Ag, M.Pd for their support through out this thesis with patience, insightful comments, and immerse knowledge. This thesis would not have been finished without their patience and encouraged guidance. Then, my special thanks are directed to Drs. Amiruddin as the supervisor who has supervised me since I was in the first semester until now. Then, my thanks to all staffs and lecturers of English departement and non Departement, and the Faculty of Tarbiyah and Teacher Training of UIN Ar-Ranirywho helped and guided me during my study in English Education Departement of UIN Ar- Raniry. Finally, I believed that this thesis was far from perfect and need to be criticized in order to be useful especially for English Departement of UIN Ar- Raniry. -

According to the Verse 30, in the Surah of Al-Furqan, the Meaning of Relationship Between Qur’An and the Society

Öneri.C.10.S.38. Temmuz 2012.145-149 ACCORDING TO THE VERSE 30, IN THE SURAH OF AL-FURQAN, THE MEANING OF RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN QUR’AN AND THE SOCIETY Faruk TUNCER Marmara University, Faculty of Theology, Assist. Professor ACCORDING TO THE VERSE 30, IN THE SURAH OF AL- FURKAN SURESİ 30. AYETE GÖRE KURAN-I KERİM’İN FURQAN, THE MEANING OF RELATIONSHIP MANEVİ ARAYIŞLARA SUNDUĞU CEVAP BETWEEN QUR’AN AND THE SOCIETY Özet: Bu makalede, Furkan suresi 30.ayete göre, Kur’an-ı Abstract: This article, according to the verse 30 in the surah of Kerim’in gerek bireysel anlamda gerekse toplumsal olarak al-furqan, will focus on spiritual search of both the individuals manevi arayış ve bunalımlar için sunduğu cevap konu and society and Qur’an’ response to that. The implementation edinmektedir. Ahlaki ve dini değerlerin manevi arayışlarda ne of moral values will be assessed and a kind of religiousity will denli önemli ve büyük bir yekün tuttuğundan hareketle, be suggested as proposed by Qur’an which places the emphasis insanlığın bu sorunlarının çözümünde Kur’an-ı Kerimin on social functions of the religion. odaklandığı nokta üzerinde durulmaktadır. Dinin toplumsal fonksiyonları üzerinde durulurken yüce kitabımıza yapılan Keywords: Qur’ann, Morality, Values, Spirituality, Mentality, vurgu üzerinde durulacaktır. Religiousity. Anahtar Kelimeler : Kur’an, ahlâk, değerler, maneviyat, dini değerler Some interpreters, like Taberi[3], project a I. INTRODUCTION different approach to these complaints. They say the Prophet (pbuh) will have his complaints on the Judgment This article will focus on spiritual search of both Day. the individuals and society and Qur’an’ response to that. -

An Islamic Perspective on Human Development Contents 1

An Islamic perspective On human development Contents 1. Introduction 1 Introduction–3 2 Fundamental principles–4 This paper relies on the primary sources of knowledge Development science is a relatively new area of 2.1 The dignity of humankind–4 in Islam, the Qur’an and Sunnah (practice and sayings knowledge in the Muslim World and is not directly 2.2 Islamic holistic worldview (tawhid)–4 of prophet Muhammad: PBUH),* to identify the key referred to in the Qur’an or Sunnah. We gain an under- 2.3 Justice–5 principles and core values that underpin Islamic views standing of it through human interpretation which is 2.4 Freedom–6 on development, poverty reduction, human rights and subject to variation, through reference to the knowledge 2.5 Human rights–6 advocacy. It will attempt to define these concepts from of religious and jurisprudential ethics as well as several 2.6 Equality–7 an Islamic point of view and present an outline of some other areas of knowledge. This paper is based on desk 2.7 Social solidarity–8 of the tools and approaches that are provided by Islam research and consultations with Islamic scholars as well 2.8 Sustainability–10 to address them. as Islamic Relief’s internal and external stakeholders. We are exploring an approach, rooted in and validated 3 Islamic Relief’s core values–11 The central argument in the paper is that development by Islamic teachings, which is most suited to provide is primarily about safeguarding and enhancing the guidance to the policy and practice of a contemporary 4 Human development–12 dignity of human beings. -

A COMPARATIVE STUDY of REFORMIST and TRADITIONALIST CONCEPTIONS of the OBJECTIVES of SHARĪ'a by OMER TASGETIREN (Under the Di

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF REFORMIST AND TRADITIONALIST CONCEPTIONS OF THE OBJECTIVES OF SHARĪ‘A by OMERTASGETIREN (Under the Direction of Alan Godlas) ABSTRACT A comparison of the ideas of the reformist Muslim thinkers Khaled Abou El Fadl and Tariq Ramadan with those of the more traditionalist scholar Yusuf al-Qaradawi illustrates that, in contrast to what is generally assumed, there is substantial common ground between these reformist and traditionalist positions in four areas; human rights and democracy, women's rights, jihād and peace, and dialogue and collaboration. This consensus among these Muslim intellectuals on these important issues has arisen because they share a theory of interpretation that necessitates the utilization of and reliance upon "objectives of Sharī‘a" (maqāṣid al- sharī‘a) to adjudicate between conflicting points of view. Since these thinkers espouse this methodology of jurisprudence and do not differ substantially concerning their views of the foundational principles of Islam, it becomes possible for them to propound similar ideas regarding the four areas mentioned above. INDEX WORDS: Khaled Abou El Fadl, Tariq Ramadan, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Objectives of Sharī‘a, Human Rights, Women Rights, Interfaith Dialogue, Democracy, Jihad A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF REFORMIST AND TRADITIONALIST CONCEPTIONS OF THE OBJECTIVES OF SHARĪ‘A by OMERTASGETIREN BA, Bogazici University, Turkey, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTEROF ARTS