2. William Eggleston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPM-Catalog-Fall-2020.Pdf

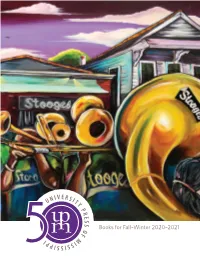

N I V E R S I U T Y P R E S S O Books for Fall–Winter 2020–2021 F M I I S P S P I I S S N I V E R S I CONTENTS U T Y P R 3 Alabama Quilts ✦ Huff / King E 9 The Amazing Jimmi Mayes ✦ Mayes / Speek S ✦ S 9 Big Jim Eastland Annis ✦ O 27 Bohemian New Orleans Weddle F 32 Breaking the Blockade ✦ Ross M ✦ I 5 Can’t Be Faded Stooges Brass Band / DeCoste I S P S P I I S S 2 Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus! ✦ Stone 33 Chaos and Compromise ✦ Pugh 23 Chocolate Surrealism ✦ Njoroge 7 City Son ✦ Dawkins OUR MISSION 12 Cold War II ✦ Prorokova-Konrad University Press of Mississippi (UPM) tells stories 31 The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume III ✦ Haney / Forrester of scholarly and social importance that impact our 18 Conversations with Dana Gioia ✦ Zheng 19 Conversations with Jay Parini ✦ Lackey state, region, nation, and world. We are commit- 19 Conversations with John Berryman ✦ Hoffman ted to equality, inclusivity, and diversity. Working 18 Conversations with Lorraine Hansberry ✦ Godfrey at the forefront of publishing and cultural trends, 21 Critical Directions in Comics Studies ✦ Giddens we publish books that enhance and extend the 8 Crooked Snake ✦ Boteler 22 Damaged ✦ Rapport reputation of our state and its universities. 10 Dan Duryea ✦ Peros Founded in 1970, the University Press of 7 Emanuel Celler ✦ Dawkins Mississippi turns fifty in 2020, and we are proud 30 Folklore Recycled ✦ de Caro of our accomplishments. -

A Road Trip Journal by Stephen Shore

Steven Shore: A Road Trip Journal by Stephen Shore Ebook Steven Shore: A Road Trip Journal currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Steven Shore: A Road Trip Journal please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 256 pages+++Publisher:::: Phaidon Press Inc.; Limited Collectors Ed edition (June 25, 2008)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0714848018+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0714848013+++Product Dimensions::::12 x 2.1 x 17.2 inches++++++ ISBN10 0714848018 ISBN13 978-0714848 Download here >> Description: Stephen Shore is one of the most influential photographers of the twentieth century, best known for his photographs of vernacular America taken in the early 1970s two bodies of work entitled American Surfaces and Uncommon Places. These projects paved the way for future photographers of the ordinary and everyday such as Martin Parr, Thomas Struth, and Nan Goldin. Shore is one of the most important artists working today, and his prints are included in collections of eminent museums and galleries around the world.On July 3, 1973, Stephen Shore set out on the road again. This road trip marked an important point in his career, as he was coming to the tail end of American Surfaces and embarking on a body of work that is known as Uncommon Places. While traveling, in addition to taking photographs, Shore also distributed a set of postcards that he had made and printed himself. While passing through Amarillo, Texas, Shore selected ten of his own photographs of places of note, such as Dougs Barb-B- Que and the Potter County Court House, and designed the back of the cards to look like a typical generic postcard. -

Alec Soth's Journey: Materiality and Time Emily Elizabeth Greer

Alec Soth’s Journey: Materiality and Time Emily Elizabeth Greer Introduction The photographer Alec Soth is known for series of images and publications that encapsulate his travels through time and place within the American landscape. Each grouping of photographs uses a specific medium and geographical orientation in order to explore unique journeys and themes, such as the loneliness and banality of strangers in a public park, religion and debauchery in the Mississippi Delta, and the isolation of hermits in the valleys of rural Montana. Yet how are we to understand the place of these smaller journeys within Soth’s larger artistic career? How are these publications and series connected to one another, and how do they evolve and change? Here, I will consider these questions as they relate to the specific materials within Soth’s work. Using material properties as a framework illuminates the way in which each series illustrates these specific themes, and also how each grouping of images holds a significant place within the artist’s larger photographic oeuvre. Throughout Alec Soth’s career, his movement between mediums has evolved in a manner that mirrors the progression of themes and subject matter within his larger body of work as a whole. From his earliest photographic forays in black and white film to his most recent digital video projects, Soth creates images that depict a meandering passage through time and place.1 His portraits, still lifes, and landscapes work together to suggest what one might call a stream of conscious wandering. The chronological progression of materiality in his works, from early black and white photography to large format 8x10 color images to more recent explorations in digital photography and film, illuminates the way in which each medium is used to tell a story of temporality and loneliness within the American landscape. -

Faltblatt Retrospective.Indd

Mexico, 1963 London, England, 1966 New York City, 1963 Paris, France, 1967 JOEL New Yok City, 1975 Five more found, New York City, 2001 MEYEROWITZ RETROSPECTIVE curated by Ralph Goertz Sarah, Cape Cod, Cape Sarah, 1981 Roseville Cottages, Truro, Massachusetts, 1976 Bay.Sky, Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1985 1978 City, York New Dancer, Young JOEL MEYEROWITZ RETROSPECTIVE Joel Meyerowitz, born and grown up in New York, belongs to a generation of photographers - together with William Eggleston, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Stephen Shore, Tony Ray-Jones and Garry Winogrand - who are equipped with a unique sensitivity towards the daily, bright, hustle and bustle on the streets, who are able to grasp a human being as an individual as well as in their social context. Starting in the early 1960s, Joel Meyerowitz went out on the streets, day in, and day out, powered by his passion and devotion to photography, in order to study people and see how photographs described what they were doing. In order to catch the vibes he ranges over the streets of New York, together with Tony Ray-Jones and later with his friend Garry Winogrand. Different from Tony Ray-Jones and Garry Winogrand, Meyerowitz loaded his camera with color film in order to capture life realistically, which meant shooting in color for him. While his first photographs are often determined in a situational way, he starts, early on, putting the subject not only in the centre, but consciously leaving the centre of the picture space free and extending the picture-immanent parts over the whole frame. His dealing with picture space and composition, which consciously differ from those of his idols like Robert Frank and Cartier-Besson, create a unique style. -

Llyn Foulkes Between a Rock and a Hard Place

LLYN FOULKES BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE LLYN FQULKES BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE Initiated and Sponsored by Fellows ol Contemporary Art Los Angeles California Organized by Laguna Art Museum Laguna Beach California Guest Curator Marilu Knode LLYN FOULKES: BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE This book has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Llyn Foulkes: Between a Rock and a Hard Place, curated by Marilu Knode, organized by Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California, and sponsored by Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California. The exhibition and book also were supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., a federal agency. TRAVEL SCHEDULE Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California 28 October 1995 - 21 January 1996 The Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati, Ohio 3 February - 31 March 1996 The Oakland Museum, Oakland, California 19 November 1996 - 29 January 1997 Neuberger Museum, State University of New York, Purchase, New York 23 February - 20 April 1997 Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs, California 16 December 1997 - 1 March 1998 Copyright©1995, Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced, in whole or in part, without permission from the publisher, the Fellows of Contemporary Art. Editor: Sue Henger, Laguna Beach, California Designers: David Rose Design, Huntington Beach, California Printer: Typecraft, Inc., Pasadena, California COVER: That Old Black Magic, 1985 oil on wood 67 x 57 inches Private Collection Photo Credits (by page number): Casey Brown 55, 59; Tony Cunha 87; Sandy Darnley 17; Susan Einstein 63; William Erickson 18; M. -

Our Choice of New and Emerging Photographers to Watch

OUR CHOICE OF NEW AND EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS TO WATCH TASNEEM ALSULTAN SASHA ARUTYUNOVA XYZA BACANI IAN BATES CLARE BENSON ADAM BIRKAN KAI CAEMMERER NICHOLAS CALCOTT SOUVID DATTA RONAN DONOVAN BENEDICT EVANS PETER GARRITANO SALWAN GEORGES JUAN GIRALDO ERIC HELGAS CHRISTINA HOLMES JUSTIN KANEPS YUYANG LIU YAEL MARTINEZ PETER MATHER JAKE NAUGHTON ADRIANE OHANESIAN CAIT OPPERMANN KATYA REZVAYA AMANDA RINGSTAD ANASTASIIA SAPON ANDY J. SCOTT VICTORIA STEVENS CAROLYN VAN HOUTEN DANIELLA ZALCMAN © JUSTIN KANEPS APRIL 2017 pdnonline.com 25 OUR CHOICE OF NEW AND EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS TO WATCH EZVAYA R © KATYA © KATYA EDITor’s NoTE Reading about the burgeoning careers of these 30 Interning helped Carolyn Van Houten learn about working photographers, a few themes emerge: Personal, self- as a photographer; the Missouri Photo Workshop helped assigned work remains vital for photographers; workshops, Ronan Donovan expand his storytelling skills; Souvid fellowships, competitions and other opportunities to engage Datta gained recognition through the IdeasTap/Magnum with peers and mentors in the photo community are often International Photography Award, and Daniella Zalcman’s pivotal in building knowledge and confidence; and demeanor grants from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting altered and creative problem solving ability keep clients calling back. the course of her career. Many of the 2017 PDN’s 30 gained recognition by In their assignment work, these photographers deliver pursuing projects that reflect their own experiences and for their clients without fuss. Benedict Evans, a client interests. Salwan Georges explored the Iraqi immigrant says, “set himself apart” because people like to work with community of which he’s a part. Xyza Bacani, a one- him. -

Notable Photographers Updated 3/12/19

Arthur Fields Photography I Notable Photographers updated 3/12/19 Walker Evans Alec Soth Pieter Hugo Paul Graham Jason Lazarus John Divola Romuald Hazoume Julia Margaret Cameron Bas Jan Ader Diane Arbus Manuel Alvarez Bravo Miroslav Tichy Richard Prince Ansel Adams John Gossage Roger Ballen Lee Friedlander Naoya Hatakeyama Alejandra Laviada Roy deCarava William Greiner Torbjorn Rodland Sally Mann Bertrand Fleuret Roe Etheridge Mitch Epstein Tim Barber David Meisel JH Engstrom Kevin Bewersdorf Cindy Sherman Eikoh Hosoe Les Krims August Sander Richard Billingham Jan Banning Eve Arnold Zoe Strauss Berenice Abbot Eugene Atget James Welling Henri Cartier-Bresson Wolfgang Tillmans Bill Sullivan Weegee Carrie Mae Weems Geoff Winningham Man Ray Daido Moriyama Andre Kertesz Robert Mapplethorpe Dawoud Bey Dorothea Lange uergen Teller Jason Fulford Lorna Simpson Jorg Sasse Hee Jin Kang Doug Dubois Frank Stewart Anna Krachey Collier Schorr Jill Freedman William Christenberry David La Spina Eli Reed Robert Frank Yto Barrada Thomas Roma Thomas Struth Karl Blossfeldt Michael Schmelling Lee Miller Roger Fenton Brent Phelps Ralph Gibson Garry Winnogrand Jerry Uelsmann Luigi Ghirri Todd Hido Robert Doisneau Martin Parr Stephen Shore Jacques Henri Lartigue Simon Norfolk Lewis Baltz Edward Steichen Steven Meisel Candida Hofer Alexander Rodchenko Viviane Sassen Danny Lyon William Klein Dash Snow Stephen Gill Nathan Lyons Afred Stieglitz Brassaï Awol Erizku Robert Adams Taryn Simon Boris Mikhailov Lewis Baltz Susan Meiselas Harry Callahan Katy Grannan Demetrius -

Michael Jackson's Gesamtkunstwerk

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 11, No. 5 (November 2015) Michael Jackson’s Gesamtkunstwerk: Artistic Interrelation, Immersion, and Interactivity From the Studio to the Stadium Sylvia J. Martin Michael Jackson produced art in its most total sense. Throughout his forty-year career Jackson merged art forms, melded genres and styles, and promoted an ethos of unity in his work. Jackson’s mastery of combined song and dance is generally acknowledged as the hallmark of his performance. Scholars have not- ed Jackson’s place in the lengthy soul tradition of enmeshed movement and mu- sic (Mercer 39; Neal 2012) with musicologist Jacqueline Warwick describing Jackson as “embodied musicality” (Warwick 249). Jackson’s colleagues have also attested that even when off-stage and off-camera, singing and dancing were frequently inseparable for Jackson. James Ingram, co-songwriter of the Thriller album hit “PYT,” was astonished when he observed Jackson burst into dance moves while recording that song, since in Ingram’s studio experience singers typically conserve their breath for recording (Smiley). Similarly, Bruce Swedien, Jackson’s longtime studio recording engineer, told National Public Radio, “Re- cording [with Jackson] was never a static event. We used to record with the lights out in the studio, and I had him on my drum platform. Michael would dance on that as he did the vocals” (Swedien ix-x). Surveying his life-long body of work, Jackson’s creative capacities, in fact, encompassed acting, directing, producing, staging, and design as well as lyri- cism, music composition, dance, and choreography—and many of these across genres (Brackett 2012). -

Five Important Lessons from HBO's Leaving Neverland Prof. Marci A

Five Important Lessons from HBO’s Leaving Neverland Prof. Marci A. Hamilton, Founder and CEO [email protected] (215) 539-1906 The 2019 HBO documentary on sex abuse by megastar, Michael Jackson, Leaving Neverland, is a valuable tool for educating parents, the public, and lawmakers on the ways in which child molesters operate. In the documentary, Wade Robson and James Safechuck describe their child sexual abuse in searing detail that bolsters their claims. They had previously supported Jackson, but that is typical of survivors, who need until the average age of 52 to disclose the abuse. 1. Child sex abusers “groom” their child victims. Child sex abusers are patient and cunning, and often the “nice guys” you want your kids to spend time with. In the film, Wade and James say that Michael Jackson offered classic gifts that are used to groom child victims: cash, candy, jewelry, special clothing (his Thriller jacket), trips, adopting endearing nicknames like “my son,” telling the children he “loves” them and their families, and other special treatment. They were told that the sex abuse was how they showed “love” to each other. Jackson also reportedly used showers, alcohol, and pornography to lower the boys’ defenses. He also told the boys and the families that God meant for them to be together. Jackson even went so far as to hold a mock wedding ceremony with a ring to “seal” their love. 2. They groom the families of the victims to get access to the children. The mothers say that Jackson spoke to them for hours at a time, curried favor with other family members, and befriended the families. -

Mitch Epstein

MITCH EPSTEIN MITCH EPSTEIN Born in 1952 in Holyoke, Massachusetts, USA He lives and works in New York EDUCATION 1972-74 The Cooper Union, New York, USA 1972-74 Rhode Island School of Design, USA 1970-71 Union College, New York, USA SELECTED GRANTS/AWARDS 2010 Winner, Prix Pictet Photography Prize: Growth 2009 Gold Medal Deutscher Fotobuchpreis, American Power Open Society Institute Documentary Photography Project Grant 2008 The American Academy in Berlin: Berlin Prize in Arts and Letters, Guna S. Mundheim Fellow in the Visual Arts, spring 2004 Kraszna-Krausz Photography Book Award, Family Business 2002 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship 1996 Camera Works, Inc. Artist Grant 1997 American Institute of Graphic Artists, 50 Best Books of the Year 1994 Pinewood Foundation Artist Grant 1980 New York State Council for the Arts Artist Fellowship 1978 National Endowment for the Arts, Individual Artist Grant SOLO EXHIBITION 2017 New York Arbor, Musée Photographique de Mougins, France Gallery Thomas Zander, Köln, Germany New York Trees, Rocks & Clouds, Galerie Les filles du calvaire, Paris, France 2016 Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, US 2013 The A Foundation, Brussels, Brussels, Belgium 2012 Gallery Thomas Zander, Köln, Germany Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, USA 2011 Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne, Switzerland Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool, UK Fondation Henri Cartier Bresson, Paris, France 2010 KunstMuseum, Bonn, Germany 2008 Brancolini Grimaldi, Rome, Italy 2007 FOAM – Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Sikkema Jenkins -

Mississippi Blues Trail Taken by David Leonard

New Stage Theatre presents Book, Lyrics, and Music by Charles Bevel, Lita Gaithers, Randal Myler, Ron Taylor and Dan Wheetman Based on an original idea by Ron Taylor Directed by Peppy Biddy Musical Direction by Sheilah Walker Choreographed by Tiffany Jefferson May 26 – June 7, 2015 Sponsored by Stage Manager Scenic Designer Elise McDonald Jimmy “JR” Robertson Projection Designer and Richart Schug Marvin “Sonny” White Technical Director/ Lighting Designer Properties Designer Brent Lefavor Richard Lawrence Costume Designer Lesley Raybon blues_program_workin2.indd 1 5/21/15 1:50 PM Originally produced on Broadway by Eric Krebs, Jonathan Reinis, Lawrence Horowitz, Anita Waxman, Elizabeth Williams, CTM Productions and Anne Squandron, in association with Lincoln Center Electric Factory Concerts, Adam & David Friedson, Richard Martini, Marcia Roberts and Murray Schwartz. The original cast album, released by MCA Records, was produced and mixed by Spencer Proffer. Photographs from the Mississippi Blues Trail taken by David Leonard. Photographs from the book “Juke Joint” taken by Birney Imes. Welty images - Copyright ©Eudora Welty, LLC; Courtesy Eudora Welty Collection – Mississippi Department of Archives and History Tomato Packer’s Recess Chopping the Field Home by Dark Carrying Ice on Sunday Morning Mother In White Dress and Child Girl with Arms Akimbo Circle of Children Madonna with Coca – Cola “It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues” is presented by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. There will be one 10 minute intermission This production of It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues is dedicated to Riley “B.B.” King September 16, 1925 – May 14, 2015 The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. -

P22 Layout 1

22 Established 1961 Lifestyle Fashion Models present creations by Cynthia Abila during the Lagos Fashion Week. — AFP photos Lagos designers champion ‘unapologetically African’ fashion ou have to struggle so hard to make your voice heard, throbbed in the background-the answer to Nigeria’s erratic Fashion designers in Lagos are being courted by inter- style off the pitch. “It’s only just gotten better, I think people that’s why Lagos will always stand out,” model Larry power supply network and a symbol of perseverance in the national tastemakers looking for talent and inspiration at a are starting to see what we have,” said Amaka Osakwe, the “YHector told AFP about Nigeria’s gritty yet unques- face of adversity. “We’re always pushing for something we time when Afrobeat and African fashion are taking the designer behind Maki Oh, one of West Africa’s most celebrat- tionably glamorous megacity Lagos. The statuesque 20-year- haven’t seen before, something that’s out of this world,” Hector United States by storm. The success of Lagos Fashion ed brands. One of Oh’s shirts, a black blouse with polka-dot old dressed in all-white was standing backstage at the Lagos said. “Now we have international people, starlets, celebrities Week, which runs until Saturday, shows the growing ruffled sleeves and lined with the name ‘Oh’ in yellow, made Fashion Week on Friday evening surrounded by a dizzying from Paris, Milan, New York, everyone is coming to see what appetite for African fashion and its invigorating colors, headlines this year after being worn by Lady Gaga on the set array of lush fabrics and gazelle-legged models.