Intergovernmental Battles Over the Creation of Health Insurance Exchanges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

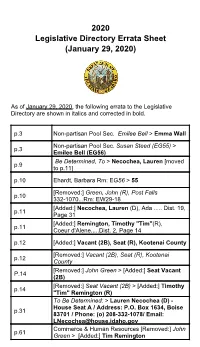

Legislative Directory Errata Sheet (January 29, 2020)

2020 Legislative Directory Errata Sheet (January 29, 2020) As of January 29, 2020, the following errata to the Legislative Directory are shown in italics and corrected in bold. p.3 Non-partisan Pool Sec. Emilee Bell > Emma Wall Non-partisan Pool Sec. Susan Steed (EG55) > p.3 Emilee Bell (EG56) Be Determined, To > Necochea, Lauren [moved p.9 to p.11] p.10 Ehardt, Barbara Rm: EG56 > 55 [Removed:] Green, John (R), Post Falls p.10 332-1070...Rm: EW29-18 [Added:] Necochea, Lauren (D), Ada ..... Dist. 19, p.11 Page 31 [Added:] Remington, Timothy "Tim"(R), p.11 Coeur d'Alene.....Dist. 2, Page 14 p.12 [Added:] Vacant (2B), Seat (R), Kootenai County [Removed:] Vacant (2B), Seat (R), Kootenai p.12 County [Removed:] John Green > [Added:] Seat Vacant P.14 (2B) [Removed:] Seat Vacant (2B) > [Added:] Timothy p.14 "Tim" Remington (R) To Be Determined: > Lauren Necochea (D) - House Seat A / Address: P.O. Box 1634, Boise p.31 83701 / Phone: (o) 208-332-1078/ Email: [email protected] Commerce & Human Resources [Removed:] John p.61 Green > [Added:] Tim Remington Health & Welfare [Removed:] John Green > p.63 [Added:] Tim Remington Local Government [Removed:] John Green > p.64 [Added:] Tim Remington p.68 Bell, Emilee EW29 > EG56 p.68 [Added:] Budell, Juanita (WG10).....332-1418 Delay, Bruce (WG48C)..... 332-1335 > p.69 (WB48B).....332-1343 Gibbs, Mackenzie EG44.....332-1050 > p.69 EW12....332-1159 Powers, Devon EW12.....332-1159 > P.71 EW46....332-1145 Shaw, Maresa EW46.....332-1145 > p.72 EG44....332-1050 p.72 [Removed:] Susan Steed p.72 [Removed:] Carol Waldrip p.72 [Added:] Wall, Emma (EW29).....332-1051 Wisdom, Rellie (WG48B).... -

Idaho Legislature Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee

Idaho Legislature Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee State Capitol Room 305 Boise, ID 83720 (208) 334 - 4735 DATE: February 3, 2011 SENATE FINANCE …………………….. TO: Senator John W. Goedde, Chairman, Senate Education Committee Dean Cameron Chairman Representative Bob Nonini, Chairman, House Education Committee Shawn Keough Vice Chairman FROM: Senator Dean L. Cameron, Chairman, Senate Finance Committee Representative Maxine T. Bell, Chairman House Appropriations Joyce Broadsword Committee Steven Bair Bert Brackett SUBJECT: Recommendations for FY 2012 Appropriation for Public Schools Dean Mortimer Please extend our heartfelt thanks to your committee members for making the Lee Heider commitment to join the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee for the budget Mitch Toryanski hearings last week. Your willingness to work together on budgetary priorities during these challenging economic times will provide support to JFAC, and hopefully together Diane Bilyeu we will provide the best possible educational opportunities for all of Idaho’s Nicole LeFavour schoolchildren. Although the Governor’s initial General Fund recommendation for Public Schools did HOUSE APPROPRIATIONS not include additional cuts – it was too optimistic considering the recent news that we …………………….. have received about revenues. We are sure you understand that once the Legislature Maxine Bell takes into consideration the reduction of projected General Fund revenues due to federal Chairman tax conformity, unanticipated sales tax credits for alternative energy, and the erosion of Darrell Bolz last year’s surplus; it is necessary to ask our germane committees to consider policy and Vice Chairman programmatic changes that support a lower spending level for FY 2012. George Eskridge The Co-Chairmen and Vice-Chairmen of JFAC have identified a range of between $50 Fred Wood million to $81 million below what the Governor recommended at $1,235,893,600 for Jim Patrick Public Schools in FY 2012. -

Download Report (PDF)

President Barack Obama The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20500 March 5, 2013 Dear President Obama, From the winding footpaths of California’s Pacific Crest Trail, to the Peak of Cadillac Mountain at Maine’s Acadia National Park, our country’s parks, forests and wildlife refuges are where Americans make some of their most cherished memories. Our nation’s public lands are an integral part of our recreational, cultural, historical and economic heritage. Yet many of these iconic landscapes are facing increasing threats from overdevelopment, pollution and underfunding. As a far-reaching coalition of groups ranging from environmentalists to veterans to hunters and anglers to local business owners and elected officials, we urge you to protect our nation’s treasured public lands. Future generations deserve the opportunity to experience these iconic pieces of our American legacy. You can help ensure their protection by calling for full funding of the Land and Water Conservation Fund in your upcoming FY14 budget proposal. Today we are sending you a list of 401 signers onto 16 state-specific letters to express the broad range of support that exists for protecting our public lands, and the programs they depend on, such as the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Each state-specific letter highlights local iconic parks, forests and wildlife refuges that are listed by that state below, along with that state’s signers to those letters. Each state’s letter to the president states: The annual diversion of Land and Water Conservation Fund funds to non-conservation purposes has left a legacy of backlogged conservation and recreation needs and missed opportunities to safeguard our natural heritage. -

How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed

Idaho Law Review Volume 50 | Number 3 Article 1 October 2014 How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review Recommended Citation Scott .W Reed, How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits, 50 Idaho L. Rev. 1 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review/vol50/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW AND WHY IDAHO TERMINATED TERM LIMITS SCOTT W. REED1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 II. THE 1994 INITIATIVE ...................................................................... 2 A. Origin of Initiatives for Term Limits ......................................... 3 III. THE TERM LIMITS HAVE POPULAR APPEAL ........................... 5 A. Term Limits are a Conservative Movement ............................. 6 IV. TERM LIMITS VIOLATE FOUR STATE CONSTITUTIONS ....... 7 A. Massachusetts ............................................................................. 8 B. Washington ................................................................................. 9 C. Wyoming ...................................................................................... 9 D. Oregon ...................................................................................... -

State of New Mexico County of Bernalillo First Judicial District Court

STATE OF NEW MEXICO COUNTY OF BERNALILLO FIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT STATE OF NEW MEXICO EX REL. THE HONORABLE MIMI STEWART, THE HONORALBE SHERYL WILLIAMS STAPLETON, THE HONORABLE HOWIE C. MORALES, THE HONORALBE LINDA M. LOPEZ, THE HONORABLE WILLIAM P. SOULES, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS— NEW MEXICO, ALBUQUERQUE FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, JOLENE BEGAY, DANA ALLEN, NAOMI DANIEL, RON LAVANDOSKI, TRACEY BRUMLIK, CRYSTAL HERRERA, and ALLISON HAWKS, Plaintiffs, v. No. ____________________ NEW MEXICO PUBLIC EDUCATION DEPARTMENT and SECRETARY-DESIGNEE HANNA SKANDERA in her official capacity, Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT AND PRELIMINARY AND PERMANENT INJUNCTIVE RELIEF COME NOW, Plaintiffs, by and through the undersigned, and for their Complaint against Defendants state as follows: I. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs bring this action against the Public Education Department and its Secretary-Designee, in her official capacity only, because Defendants have implemented a fundamental change in the manner in which teachers are evaluated in New Mexico. As detailed in this Complaint, that change is based on a fundamentally, and irreparably, flawed methodology which is further plagued by consistent and appalling data errors. As a result, teachers are being evaluated, and employment decisions made, based on a process that is, at best, arbitrary and capricious. 2. Due to the problems with the evaluation methodology detailed herein, Defendants have or are about to violate Plaintiffs’ constitutional rights, violate the statutory authority under which they operate, and violate other provisions of law. Plaintiffs seek declaratory and injunctive relief. II. PARTIES, JURISDICTION, AND VENUE 3. Plaintiff the Honorable Senator Mimi Stewart is the elected Senator from District 17 (Bernalillo County). -

SENATE DIRECTORY Name SENATE OFFICE Locationscommittee Assignments Party Affiliation (C) - Chair, (VC) - Vice Chair House State Capitol Building Connie B

SENATE DIRECTORY Name SENATE OFFICE LOCATIONSCommittee Assignments Party Affiliation (C) - Chair, (VC) - Vice Chair House State Capitol Building Connie B. Binsfeld Building Boji Tower District HomeP.O. Address Box 30036 Lansing Office201 Townsend Street (MVC) -124 Minority West ViceAllegan Chair Street and Senate Leadership Position andLansing, Telephone MI 48909-7536 and Telephone Lansing, MI 48933 (M) - MemberLansing, MI 48933 Service Name Committee Assignments Party Affiliation (C) - Chair, (VC) - Vice Chair House District Home Address Lansing Office (MVC) - Minority Vice Chair and Senate Leadership Position and Telephone and Telephone (M) - Member Service Senator Jim Ananich 932 Maxine Street Capitol Bldg. Agriculture (MVC) House: Democrat Flint, MI 48503 P.O. Box 30036 Government Operations (MVC) 1/1/11 - 5/12/13 27th District Lansing, MI 48909-7536 Legislative Council (M) Senate: Minority Leader Room S-105 5/13/13 - Present 5 (517) 373-0142 Fax: (517) 373-3938 E-mail: [email protected] Website: senatedems.com/ananich Senator Steven M. Bieda 32721 Valley Drive Connie B. Binsfeld Bldg. Economic Development & International House: Democrat Warren, MI 48093 P.O. Box 30036 Investment (M) 1/1/03 - 12/31/08 9th District (586) 979-5387 Lansing, MI 48909-7536 Finance (MVC) Senate: Assistant Minority Room 6300 Insurance (MVC) 1/1/11 - Present Leader (517) 373-8360 Judiciary (MVC) Fax: (517) 373-9230 Legislative Council (Alt. M) Toll-free: (866) 262-7309 Michigan Capitol Committee (M) E-mail: [email protected] Michigan Commission on Uniform State Laws (M) Website: senate.michigan.gov/bieda SENATE DIRECTORY Name Committee Assignments Party Affiliation (C) - Chair, (VC) - Vice Chair House District Home Address Lansing Office (MVC) - Minority Vice Chair and Senate Leadership Position and Telephone and Telephone (M) - Member Service Senator Darwin L. -

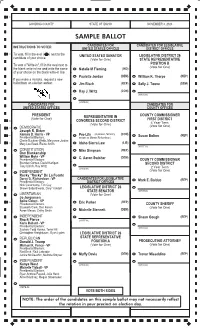

Sample Ballot May Not Necessarily Reflect the Rotationofficial in STAMP Your BOX Precinct on Election Day

11 GOODING COUNTY STATE OF IDAHO NOVEMBER 3, 2020 GOODING RURAL OFFICIALSAMPLE GENERAL BALLOTELECTION BALLOT CANDIDATES FOR CANDIDATES FOR LEGISLATIVE INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER UNITED STATES OFFICES DISTRICT OFFICES 21 To vote, fill in the oval ( ) next to the UNITED STATES SENATOR LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 26 candidate of your choice. (Vote for One) STATE REPRESENTATIVE To vote a "Write-in", fill in the oval next to POSITION B (Vote for One) the blank write-in line and write the name Natalie M Fleming (IND) of your choice on the blank write-in line. Paulette Jordan (DEM) William K. Thorpe (REP) If you make a mistake, request a new ballot from an election worker. Jim Risch (REP) Sally J. Toone (DEM) Ray J. Writz (CON) (WRITE-IN) (WRITE-IN) CANDIDATES FOR CANDIDATES FOR UNITED STATES OFFICES COUNTY OFFICES PRESIDENT REPRESENTATIVE IN COUNTY COMMISSIONER (Vote for One) FIRST DISTRICT 40 CONGRESS SECOND DISTRICT (Vote for One) 4 Year Term (Vote for One) 41 DEMOCRATIC Joseph R. Biden (a person, formerly known as Marvin Richardson) (A person, formerly 42 Kamala D. Harris - VP Pro-Life (CON) (REP) Presidential Electors: known as Marvin Richardson) Susan Bolton Cherie Buckner-Webb, Maryanne Jordan 43 Mary Lou Reed, Elaine Smith Idaho Sierra Law (LIB) (WRITE-IN) CONSTITUTION Mike Simpson (REP) Don Blankenship William Mohr - VP (DEM) Presidential Electors: C. Aaron Swisher COUNTY COMMISSIONER Brendan Gomez, David Hartigan SECOND DISTRICT Tony Ullrich, Ray Writz (WRITE-IN) 2 Year Term INDEPENDENT (Vote for One) Rocky "Rocky" De La Fuente Darcy G. Richardson - VP CANDIDATES FOR LEGISLATIVE (REP) Presidential Electors: DISTRICT OFFICES Mark E. -

2010 Legislative Directory

TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS Senate Leadership and Administration ................................. 2 House Leadership and Administration .................................. 3 Legislative Staff Offices ......................................................... 4 Legislative Council ................................................................. 5 Important Session Dates ....................................................... 5 Senators, Alphabetical ........................................................... 6 Representatives, Alphabetical ............................................... 8 Legislators by District ............................................................12 Floor Maps .............................................................................47 Senate Committees ...............................................................55 House Committees ................................................................59 Legislative Attachés & Support Staff .....................................66 State Government ..................................................................72 Elected Officials .....................................................................80 Capitol Correspondents .........................................................82 Orders of Business ................................................................84 How to Contact Legislators Web Site .................................... www.legislature.idaho.gov Informationneed at end Center to justify ......................................... 208-332-1000 Tollneed -

2018 Michigan State Senate Race September 2017

2018 Michigan State Senate Race September 2017 This is a preliminary report on the 2018 Michigan State Senate races. It includes filed and prospective candidates from each of the 38 Senate districts along with district maps and current Senators. The information in this document is taken from multiple sources. Updates will be made as Senate races progress. If you have any questions or comments please contact us at Public Affairs Associates. 1 1st District Current Senator: Coleman A. Young, Jr. (D-Detroit), (term-limited) Filed: Rep. Stephanie Chang (D-Detroit) Nicholas Rivera (D), Admissions Counselor at Wayne State University Prospective: Rep. Bettie Cook Scott (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Alberta Tinsley-Talabi (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Detroit). Rep. Tlaib’s run is a possibility, but with Chang in the race it’s questionable. Rico Razo, Mayor Mike Duggan’s re-election campaign manager Denis Boismier, Gibraltar City Council President. Although Boismier is running for Gibraltar mayor this year, he may possibly join the race if the field becomes heavily saturated with Detroit candidates. 2 2nd District Current Senator: Bert Johnson (D-Highland Park), (term-limited) Filed: Tommy Campbell (D-Grosse Pointe) Rep. Brian Banks (D-Harper Woods) Adam Hollier, former aide to Sen. Johnson Prospective: Former Rep. Lamar Lemmons (D-Detroit) Former Rep. John Olumba (D-Detroit) 3 3rd District Current Senator: Morris Hood III (D-Detroit), (term-limited) Filed: N/A Prospective: Rep. Sylvia Santana (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Harvey Santana (D-Detroit) Former Rep. David Nathan (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Gary Woronchak (R-Dearborn), current Wayne County Commission Chair 4 4th District Current Senator: Ian Conyers (D-Detroit), (Incumbent) Filed: N/A Prospective: N/A 5 5th District Current Senator: David Knezek (D-Dearborn Heights), (Incumbent) Filed: DeShawn Wilkins (R-Detroit) Prospective: N/A 6 6th District Current Senator: Hoon-Yung Hopgood (D-Taylor), (term-limited) Filed: Rep. -

Just Like Palin

Just like Palin Marty Trillhaase/Lewiston Tribune JEERS ... to Sherri Ybarra, the GOP's nominee for state schools superintendent and honors graduate of the Sarah Palin Academy of Prevarication. As Idaho Education News' Clark Corbin reported, Ybarra has missed 15 of the past 17 elections. Last spring, Corbin had established she took a pass on the 2012 election - in which outgoing Superintendent Tom Luna's controversial school overhaul package was repealed. Now Corbin reveals Ybarra didn't bother to vote in the 2006 election - in which then-Gov. Jim Risch's maintenance and operation tax shift was on the ballot. That shift destabilized school funding throughout the state. Also up for consideration that year was an unsuccessful proposal to increase Idaho's sales tax and earmark the dollars for schools. All told, Ybarra has missed four elections for state superintendent of public instruction, four elections for governor and four elections for president. None of this was known Sept. 26, when she told the City Club of Boise, "We have all missed an election or two in our lifetime, and I am not exempt from that." When pressed during a debate with Democrat Jana Jones on Boise's KTVB, Ybarra continued to equivocate: "It's not news that I've been sporadic with my voting behavior." Responded Corbin: "That's not exactly the whole story." In true Palin fashion, Ybarra then pivoted: She was running for the $102,667 job to atone. "That's why I'm here, because I have not been very good at my civic duties and I want to repay Idaho," she said. -

2013 Freedom Index Report

2013 Freedom Index Report Dear Friend of Freedom, On behalf of the board of directors of Idaho Freedom Foundation and our dedicated team of policy analysts and reporters, it is my honor to present you with our 2013 Idaho Freedom Index® Report. The Idaho Freedom Index examines legislation for free market principles, constitutionality, regulatory growth and other defined metrics. The examination then results in a numeric value being assigned to each bill having an impact on economic freedom and growth of government. We then take those numeric values and tally each legislator’s House or Senate floor votes to see whether that legislator, in total, supported or opposed economic freedom. Before the Idaho Freedom Index came along, it was nearly impossible to speak knowledgeably about a legislator’s commitment or opposition to free market ideals. We basically had to take politicians at their word regarding their cumulative voting performance. Today, voters, taxpayers and other interested observers can use our data to see whether lawmakers vote in support of bigger or smaller government, economic liberty or statism. Legislators routinely check our Freedom Index analyses before they cast their votes, and members of the public also check the Index to see how their legislators are performing. Our policy analysts worked tirelessly throughout the session to make sure lawmakers and the public had timely, accurate and substantive information during the 88-day legislative session. None of this work would be possible without the generous support of freedom-loving Idahoans, who continue to make a financial investment in the Idaho Freedom Foundation. If you are one of our dedicated donors, I offer you my humble and heartfelt gratitude. -

Federal Lands Interim Committee Thursday, October 09, 2014 6:30 P.M

MINUTES (Subject to approval by the Committee) Federal Lands Interim Committee Thursday, October 09, 2014 6:30 P.M. City Council Chambers City Hall Soda Springs, Idaho Cochairman Senator Chuck Winder called the meeting to order. Other members present were Cochairman Representative Lawerence Denney, Senator John Tippets, Senator Sheryl Nuxoll, Senator Michelle Stennett, Representative Terry Gestrin and Representative Mat Erpelding. Senator Bart Davis, Representative Mike Moyle and Representative Stephen Hartgen were absent and excused. Mike Nugent was the LSO staff member present. Other persons present were Lori Anne Lau, Caribou County Farm Bureau; Mark Harris; Jon Goode, Agrium; Bob Geddes, Idaho Farm Bureau and Chad Harris. Mr. Mike Nugent, LSO staff, gave background information on the committee's charge. He explained that the purpose of the committee is to give the Legislature more time to study the subject that is too complex to complete during the regular legislative session. This committee is a two-year committee that ceases to exist after November 30, 2014. In order to continue beyond that date the Legislature will have to approve another concurrent resolution or enact a statute. The committee was formed pursuant to the adoption of HCR21 and HCR22 during the 2013 Legislature. He also explained that all information from past meetings is available on the LSO website at: www.legislature.idaho.gov Written testimony was also accepted by the committee and that is posted at: http://www.legislature.idaho.gov/sessioninfo/2014/interim/lands.htm Senator Winder explained that this is going to be a long-term process that will probably require a recommendation for some type of land commission to pursue the opportunities that are out there regarding federal land transfers.