Collective Action and Rationality in the Anti-Terror Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Call to Censure the President

S. HRG. 109–524 AN EXAMINATION OF THE CALL TO CENSURE THE PRESIDENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 31, 2006 Serial No. J–109–66 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 28–341 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Cornyn, Hon. John, a U.S. Senator from the State of Texas .............................. -

Dear Virginians, Five Generations Ago, My Ancestors Were Freed from the Shackles of Slavery

REFORMING OUR CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM Dear Virginians, Five generations ago, my ancestors were freed from the shackles of slavery. Just two generations ago, my grandfather, one of Virginia’s first Black lawyers, was forced by Jim Crow to obtain his law degree in the north. And my father was one of the first to integrate his elementary school in 1960. As I travel throughout the Commonwealth and stand as an elected official in the former capital of the Confederacy, I often wonder how my ancestors would feel, and what they would think, about their descendant who has the opportunity to be Virginia’s first Black Attorney General. I’m running for Attorney General because we’ve made progress in building a more fair and equitable Virginia, but we all know we have not come far enough. The vestiges of slavery and Jim Crow live on in our Commonwealth’s criminal code, in our judicial system, and in our policing. They criminalize Black and Brown communities and make every Virginian less safe. In order to embrace the new Virginia decade, we must build a justice system that works for everybody in our Commonwealth, not just a select few. We have arrived at a true moment of opportunity in our country and in our Commonwealth. We must elect leaders who will rise to that moment and seize the chance to create real change in our justice system, rather than continuing with those who have proven time and time again that they will only do the bare minimum to get by. For his entire career, Mark Herring has shown that he will follow when he has to, but he will not lead. -

AB 1578: the End of Marijuana Prohibition As We Know It?, 49 U

The University of the Pacific Law Review Volume 49 | Issue 2 Article 15 1-1-2018 AB 1578: The ndE of Marijuana Prohibition as We Know It? Trevor Wong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uoplawreview Part of the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Trevor Wong, AB 1578: The End of Marijuana Prohibition as We Know It?, 49 U. Pac. L. Rev. 449 (2017). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uoplawreview/vol49/iss2/15 This Legislative Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Law Reviews at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The nivU ersity of the Pacific Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interaction Between State and Federal Law Enforcement AB 1578: The End of Marijuana Prohibition as We Know It? Trevor Wong Code Section Affected Health and Safety Code §§ 11362.6 (new); AB 1578 (Jones-Sawyer). TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 450 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND .................................................................................. 452 A. California’s Law Prior to AB 1578 ....................................................... 453 B. Federal Guidelines for Handling Marijuana Law ................................ 456 C. Economic Context ................................................................................. 459 D. Constitutionality ................................................................................... -

Professor C. Raj Kumar Professor & Vice Chancellor O.P

Curriculum Vitae PROFESSOR C. RAJ KUMAR PROFESSOR & VICE CHANCELLOR O.P. JINDAL GLOBAL UNIVERSITY Tel: (+91-130) 4091900; Fax: (+91-130) 4091888 Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.jgu.edu.in I. CURENT AFFILIATION (since 2009) Vice Chancellor, O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana (NCR of Delhi) Dean, Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat, Haryana (NCR of Delhi) Director, International Institute for Higher Education Research & Capacity Building, Sonipat, Haryana (NCR of Delhi) II. EDUCATION Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Doctor of Legal Science (S.J.D.), 2011 Harvard Law School, United States of America LL.M. (Master of Laws), 2000. University of Oxford, United Kingdom B.C.L. (Bachelor of Civil Law), 1999. Faculty of Law, University of Delhi, India LL.B. (Bachelor of Laws), 1997. Loyola College, University of Madras, India B.Com. (Bachelor of Commerce), 1994. III. AWARDS/SCHOLARSHIPS/FELLOWSHIPS (ANNEX I) Scholarships and fellowships awarded by the University of Oxford, Harvard Law School, Harvard University, Loyola College, University of Madras, Monash University and Indiana University. IV. RESEARCH GRANTS/FUNDS (ANNEX II) Received research grants and funds from various educational and research institutions, foundations, and inter-governmental organisations including City University of Hong Kong; Sumitomo Foundation, Tokyo, Japan; and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). V. PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Passed the New York Bar Exam (July 2001) and was admitted to the Bar of the State of New York, U.S.A., as an Attorney and Counsellor at Law in February 2002; admitted to the Bar Council of Delhi, New Delhi, India, in August 1997. -

Attendee Handout Packet 7.30.2020 AAM Webinar

Association of Attorney-Mediators Webinar - Confidentiality in the Age of Online Mediations: Points to Ponder July 30, 2020 On July 30, 2020, from 11:30 a.m. to 12:45 p.m., the Association of Attorney Mediators will be presenting a webinar during which a moderator and four panelists will discuss the issues of confidentiality and discoverability that come with conducting mediations on platforms such as Zoom, with participants often in different states with different laws that govern mediation confidentiality. The panelists and moderator are from across the United States, as will be the attendees. The following panel members will discuss the enforceability of Confidentiality Agreements, the conflicts of laws principles that arise with multi-state mediations, the potential liability for confidentiality breaches of which mediators must be aware, and other salient issues. Panelists will be Danielle Hargrove, Jeff Kichaven, Jean Lawler and Michael Leech. Panel will be moderated by AAM President, Jimmy Lawson. Agenda 11:30-11:35: Welcome and Introduction of Panel Jimmy Lawson, Moderator 11:35-11:45: Brief synopsis of the substance of Kichaven’s articles Jeff Kichaven, Panelist 11:45-12:45 Discussion of mediation confidentiality. Various questions will be asked of the panel for discussion Table of Contents Speakers Bios Pages 2-3 Article: Mediator Confidentiality Promises Carry Serious Risks Pages 4-6 Article: What You Say In Online Mediation May Be Discoverable Pages 7-12 Article: Nix Your Mediators Prospective Waiver Of Liability Pages 13-16 1 Association of Attorney-Mediators Webinar - Confidentiality in the Age of Online Mediations: Points to Ponder Speakers and Panelists – July 30, 2020 Danielle L. -

Looking Back to Go Forward: Remaking Detainee Policy*

Looking Back to Go Forward: Remaking U.S. Detainee Policy* by James M. Durant, III, Lt Col USAF Deputy Head, Department of Law United States Air Force Academy Frank Anechiarico Distinguished Visiting Professor of Law United States Air Force Academy Maynard-Knox Professor of Government and Law Hamilton College [WEB VERSION] April, 2009 © James Durant, III, Frank Anechiarico * This article does not reflect the views of the Air Force, the United States Department of Defense, or the United States Government. “By mid-1966 the U.S. government had begun to fear for the welfare of American pilots and other prisoners held in Hanoi. Captured in the midst of an undeclared war, these men were labeled war criminals. .Anxious to make certain that they were covered by the Geneva Conventions and not tortured into making ‘confessions’ or brought to trial and executed, U.S. Ambassador-at-Large Averell Harriman asked [ New Yorker correspondent Robert] Shaplen to contact the North Vietnamese.” - Thomas Bass (2009) ++ Introduction This article, first explains why and how detainee policy as applied to those labeled enemy combatants, collapsed and failed by 2008. Second, we argue that the most direct and effective way for the Obama Administration to reassert the rule of law and protect national security in the treatment of detainees is to direct review and prosecution of detainee cases to U.S. Attorneys and adjudication of charges against them to the federal courts. The immediate relevance of this topic is raised by the decision of the Obama Administration to use the federal courts to try Ali Saleh Kahah al-Marri in a (civilian) criminal court. -

Home Study Programs Accredited As of Friday, August 13, 2021 General Ethics Course ID Seminar Name Provider Date Credits Credits

Home Study Programs Accredited as of Friday, September 3, 2021 General Ethics Course ID Seminar Name Provider Date Credits Credits 775960 TECH POLICIES FOR LAW FIRMS ABA 2019 2 780042 #ITSMYLANE:LGL MEDICAL ETHICS ABA 2019 2 0 788385 #METOO CLASS ACTION UPDATES ABA 2020 1 0 787888 100 YEARS ACCESS TO JUSTICE ABA 2020 1 0 775395 1031 EXCHANGES: NEW TAX ACT ABA 2018 2 770878 1041 FIDUCIARY INCOME TAX RTRN ABA 2019 2 790283 1782 CONUNDRUM ABA 2020 2 778467 19TH AMEND THEN & NOW: 21ST CE ABA 2019 2 0 791776 1-A SHARPER FOCUS: 43RD ANNL ABA 2020 4 788727 20 FED PROCURMNT ETHICS SOCIAL ABA 2020 3 2.4 788725 20 FED PROCURMNT:ADR ABA 2020 2 0 788728 20 FED PROCURMNT:GOV CONSTUCT ABA 2020 2 0 788726 20 FED PROCURMNT:WHITHER WHETH ABA 2020 2 0 775850 2017 SANCTIONS YEAR IN REVIEW ABA 2019 2 776071 2017 TAX ACT, ADVICE & ETHICS ABA 2019 2 1.8 775572 2017 TAX ACT: CORP TRANSACTNS ABA 2018 2 775609 2017 TAX ACT: FIRM PLANNING ABA 2018 2 775554 2017 TAX ACT: LAW FIRM PLAN ABA 2018 2 775532 2017 TAX ACT: NEED TO KNOW ABA 2018 2 775859 2017 TAX REFORM: YOUR FIRM ABA 2019 2 776201 2017 TAX REFORM: YOUR FIRM ABA 2017 1 775860 2017 US EXPORT CONTROLS ABA 2019 2 775607 2018 SUPREME COURT TERM ABA 2018 2 775380 2018 TAX ACT: REAL ESTATE LWYR ABA 2018 2 784443 2019 CORONAVIRUS: PUB HEALTH ABA 2020 2 0 780047 2019 ESTATE PLANNING HOT TOPIC ABA 2019 2 0 784491 2019 PRIVATE TARGET DEAL POINT ABA 2020 2 0 784557 2020 E-DISCOVERY:ETHICS ABA 2020 2 1.2 784558 2020 E-DISCOVERY:FORENS DATA ABA 2020 4 0 785980 2020 ILS VAM BEWARE FINE PRINT ABA 2020 2 0 785983 2020 -

Experts Say Conway May Have Broken Ethics Rule by Touting Ivanka Trump'

From: Tyler Countie To: Contact OGE Subject: Violation of Government Ethics Question Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 11:26:19 AM Hello, I was wondering if the following tweet would constitute a violation of US Government ethics: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/829356871848951809 How can the President of the United States put pressure on a company for no longer selling his daughter's things? In text it says: Donald J. Trump @realDonaldTrump My daughter Ivanka has been treated so unfairly by @Nordstrom. She is a great person -- always pushing me to do the right thing! Terrible! 10:51am · 8 Feb 2017 · Twitter for iPhone Have a good day, Tyler From: Russell R. To: Contact OGE Subject: Trump"s message to Nordstrom Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:03:26 PM What exactly does your office do if it's not investigating ethics issues? Did you even see Trump's Tweet about Nordstrom (in regards to his DAUGHTER'S clothing line)? Not to be rude, but the president seems to have more conflicts of interest than someone who has a lot of conflicts of interests. Yeah, our GREAT leader worrying about his daughters CLOTHING LINE being dropped, while people are dying from other issues not being addressed all over the country. Maybe she should go into politics so she can complain for herself since government officials can do that. How about at least doing your jobs, instead of not?!?!? Ridiculous!!!!!!!!!!!! I guess it's just easier to do nothing, huh? Sincerely, Russell R. From: Mike Ahlquist To: Contact OGE Cc: Mike Ahlquist Subject: White House Ethics Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:23:01 PM Is it Ethical and or Legal for the Executive Branch to be conducting Family Business through Government channels. -

Trump's Deadly Legacy: the First Six Months

Trump’s Deadly Legacy: The First Six Months, Timeline of US Policy Changes, News Highlights Mainstream Media Review (January 20-July 19, 2017) By Michael T. Bucci Region: USA Global Research, July 20, 2017 michaelbucci.com Note: With few exceptions, sources are from mainstream media. GR Editor’s Note: This compilation does not constitute an endorsement of the mainstream media stories below. The list of news headline stories is intended to reveal the details of a political timeline, namely a sequence of key policy decisions taken since the inception of the Trump administration on January 19, 2017. These key policy decisions have been the object of mainstream media coverage. * * * January 20, 2017 Trump Inauguration (Friday): – Trump signs first executive action canceling Obama’s FHA mortgage rate premium cuts https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-20/trump-administration-overturns-obam a-s-fha-mortgage-fee-cut – Trump signs executive order to roll-back Obamacare hours after taking office http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/20/politics/trump-signs-executive-order-on-obamacare/ – Trump writes memo temporarily banning new federal government regulations. http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/20/politics/reince-priebus-regulations-memo/ January 21, 2017 (Saturday) – Massive Women’s March in U.S. and World. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/01/21/world/womens-march-pictures.html http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/21/politics/trump-women-march-on-washington/ http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/peace-positivity-massive-women-s-march-make-voi ces-heard-d-n710356 http://www.cbsnews.com/news/womens-march-washington-chicago-massive-turnout-change | 1 -of-plans/ http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/01/women-world-protest-president-trump-1701211344 24671.html http://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/315442-massive-womens-march-crowds-sw arm-dc-metro – U.S. -

SPARTAN DAILY - EDICIÓN EN ESPAÑOL SEE FULL STORY on PAGE 3 Information from Weather.Gov

WEEKLY WEATHER WIREE ¡Próximamente! BAILE FOLKLORICO TUE WED THU FRIF — El 23 de febrero del 2017 — H 60 H 57 H 56 H 57 L 53 L 38 L 38 L 42 SPARTAN DAILY - EDICIÓN EN ESPAÑOL SEE FULL STORY ON PAGE 3 Information from weather.gov FOLLOW US! /spartandaily @SpartanDaily @spartandaily /spartandailyYT Volume 148. Issue 11www.sjsunews.com/spartandaily Tuesday, February 21, 2017 ANTI-TRUMP Not My President’s Day takes San Jose by storm BY KYLEE BAIRD AND chants demonstrators yelled. members of the crowd to ELIZABETH RODRIGUEZ Attendees also held signs come up and share their STAFF WRITERS which read “Be the change stories or express themselves. you want to see in the world” The crowd later moved to WATCH THIS VIDEO ON accompanied with a photo the sidewalk where people YOUTUBE AT SPARTANDAILY of Mahatma Gandhi and a held their signs. Cars honked banner which read “Not My as they passed. In the heavy rain, protesters President.” Similar to other protests came out with waterproof “I am so disgusted by since Trump won the signs to object President him,” said Danielle Perri, an presidency back in Donald Trump for the administrative specialist and November, people continued “Not My Presidents Day” San Jose State University to raise awareness for several demonstration at San Jose alumna. “I am so glad to other issues including City Hall on Monday. see you. We are not done immigration, women’s rights, The event was co- marching, we are not done LGBTQ rights, Black Lives sponsored by South Bay fi ghting. And we will win.” Matter, education and the resistance groups, Orchard As the rain poured the Dakota Access Pipeline. -

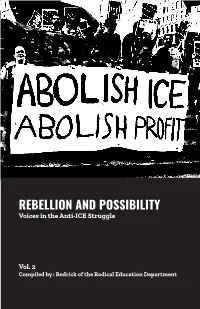

REBELLION and POSSIBILITY Voices in the Anti-ICE Struggle

REBELLION AND POSSIBILITY Voices in the Anti-ICE Struggle Vol. 2 Compiled by : Redrick of the Radical Education Department RADICAL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Published by the Radical Education Department (RED) 2018 Radical Education Department radicaleducationdepartment.com [email protected] Notes: Many thanks to the comrades in RED with whom these ideas were created and developed, and to It’s Going Down, whose site first published many of the collected writings here and who helped point us towards many of these writings. And our deepest gratitude to all the comrades in the anti-ICE struggles past, present, and future. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to Volume II .................................................................................5 VOLUME II: MORE VOICES IN THE STRUGGLE Roots of Anti-Immigrant Policy in the United States 1. NoName Collective, “Abomination 2.0 – A new old crisis” ..................6 PHILADELPHIA 2. Arthur Burbridge, “Dispatch from Occupy ICE Philly” ......................24 3. Friendly Fire, “Beyond Occupation: Thoughts on the current #OccupyICEPHL and moving forward to #EndPARS” .......................32 4. “This Movement Isn’t Ours—it’s Everybody’s” ......................................36 PORTLAND 5. Selection from Crimethinc, “The ICE Age Is Over: Reflections from the ICE Blockades” ....................................................................................42 6. Crimethinc, “Occupy ICE Portland: Policing Revolution? Lessons from the Barricades” .................................................................................50 -

Jan. 26, 2017, Vol. 59, No. 4

• MIGRACIÓN CUBANA • OSCAR LÓPEZ RIVERA 12 San Francisco Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 59, No. 4 Jan. 26, 2017 $1 ‘Resist Trump’ goes global Millions join women’s marches By Monica Moorehead It is estimated that more than 4 million people, the have so many people come out in the streets on the same vast majority of them women, participated in women’s day in solidarity and resistance — this time with wom- Consider these astounding numbers: 750,000 in Los marches in more than 500 U.S. cities. They also protest- en’s rights the major focus. Due to the sheer numerical Angeles; 500,000 in Washington, D.C.; 500,000 in New ed in more than 100 cities outside the U.S. — on every magnitude of these demonstrations, the J21 marches York City; 250,000 in Chicago; 150,000 in San Francis- continent, including Antarctica. These estimated num- could not be ignored by the mainstream media or the co; 150,000 in Boston; 150,000 in Denver; 100,000 in bers were compiled by Jeremy Pressman (@djpressman) incoming Trump administration. Oakland; 100,000 in London. These numbers represent at the University of Connecticut and Erica Chenoweth (@ What started out as a modest call for a Jan. 21 march some of the largest demonstrations that took place on ericachenoweth) at the University of Denver based on nu- against Trump by one Hawai’i-based woman on Face- Jan. 21, ignited by the inauguration of the racist, mi- merous media reports, including Facebook and Twitter.