Access to and Utilisation of Professional Child Delivery Services in Uganda and Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Health

UGANDA PROTECTORATE Annual Report of the MINISTRY OF HEALTH For the Year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 Published by Command of His Excellency the Governor CONTENTS Page I. ... ... General ... Review ... 1 Staff ... ... ... ... ... 3 ... ... Visitors ... ... ... 4 ... ... Finance ... ... ... 4 II. Vital ... ... Statistics ... ... 5 III. Public Health— A. General ... ... ... ... 7 B. Food and nutrition ... ... ... 7 C. Communicable diseases ... ... ... 8 (1) Arthropod-borne diseases ... ... 8 (2) Helminthic diseases ... ... ... 10 (3) Direct infections ... ... ... 11 D. Health education ... ... ... 16 E. ... Maternal and child welfare ... 17 F. School hygiene ... ... ... ... 18 G. Environmental hygiene ... ... ... 18 H. Health and welfare of employed persons ... 21 I. International and port hygiene ... ... 21 J. Health of prisoners ... ... ... 22 K. African local governments and municipalities 23 L. Relations with the Buganda Government ... 23 M. Statutory boards and committees ... ... 23 N. Registration of professional persons ... 24 IV. Curative Services— A. Hospitals ... ... ... ... 24 B. Rural medical and health services ... ... 31 C. Ambulances and transport ... ... 33 á UGANDA PROTECTORATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Annual Report For the year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 I.—GENERAL REVIEW The last report for the Ministry of Health was for an 18-month period. This report, for the first time, coincides with the Government financial year. 2. From the financial point of view the year has again been one of considerable difficulty since, as a result of the Economy Commission Report, it was necessary to restrict the money available for recurrent expenditure to the same level as the previous year. Although an additional sum was available to cover normal increases in salaries, the general effect was that many economies had to in all be made grades of staff; some important vacancies could not be filled, and expansion was out of the question. -

Croc's July 1.Indd

CLASSIFIED ADVERTS NEW VISION, Monday, July 1, 2013 57 BUSINESS INFORMATION MAYUGE SUGAR INDUSTRIES LTD. SERVICE Material Testing EMERGENCY VACANCIES POLICE AND FIRE BRIGADE: Ring: 999 or 342222/3. One of the fastest developing and THE ONLY 6. BOILER ATTENDANT - 3 Posts Africa Air Rescue (AAR) 258527, MANUFACTURER OF SULPHURLESS SUGAR IN Boiler Attendant Certificate Holders with 3-5 258564, 258409. EAST AFRICA based in Uganda. The organization yrs working experience preferred (Thermo ELECTRICAL FAILURE: Ring is engaged in the manufacturing of “Nile Sugar” fluid handling) UMEME on185. and soon starting the manufacturing of Extra 7. SR. ELECTRICAL & INSTRUMENTATION ENGR. MATERIAL TESTING AND SURVEY EQUIPMENT Water: Ring National Water and Neutral Alcohol Invites applications for below - 1Post Sewerage Corporation on 256761/3, 242171, 232658. Telephone inquiry: posts; B.E.(electrical & instrumentation) or equallent Material Testing UTL-900, Celtel 112, MTN-999, 112 1. SHIFT CHEMIST FOR DISTILLATION - 3 Posts with experience of 15 years FUNERAL SERVICES Must have 3-5 years of experience in PLC/ 8. ELECTRICAL ENGR - 1 Post Aggregates impact Value Kampala Funeral Directors, SKADA system independent operation . Diploma in Electrical Engr.or equallent with Apparatus Bukoto-Ntinda Road. P.O. Box 9670, Qualification :-B.SC.Alco,Tech or Diploma in exp of 5 yrs Flakiness Gauge&Flakiness Chem Eng. 9. INSTRUMENTATION ENGR. - 1 Post Kampala. Tel: 0717 533533, 0312 Sleves 533533. 2. LABORATORY CHEMIST SHIFT - 3 Posts Diploma in Instrumentation or equallent with Los Angeles Abrasion Machine Uganda Funeral Services For Mol Analysis /Spirit Analysis /Q.C exp of 5 yrs H/Q 80A Old Kira Road, Bukoto Checking/Spent wash loss checking etc 10. -

UG-08 24 A3 Fistula Supported Preventive Facilities by Partners

UGANDA FISTULA TREATMENT SERVICES AND SURGEONS (November 2010) 30°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 34°0'0"E Gulu Gulu Regional Referral Hospital Agago The Republic of Uganda Surgeon Repair Skill Status Kalongo General Hospital Soroti Ministry of Health Dr. Engenye Charles Simple Active Surgeon Repair Skill Status Dr. Vincentina Achora Not Active Soroti Regional Referral Hospital St. Mary's Hospital Lacor Surgeon Repair Skill Status 4°0'0"N Dr. Odong E. Ayella Complex Active Dr. Kirya Fred Complex Active 4°0'0"N Dr. Buga Paul Intermediate Active Dr. Bayo Pontious Simple Active SUDAN Moyo Kaabong Yumbe Lamwo Koboko Kaabong Hospital qÆ DEM. REP qÆ Kitgum Adjumani Hospital qÆ Kitgum Hospital OF CONGO Maracha Adjumani Hoima Hoima Regional Referral Hospital Kalongo Hospital Amuru Kotido Surgeon Repair Skill Status qÆ Arua Hospital C! Dr. Kasujja Masitula Simple Active Arua Pader Agago Gulu C! qÆ Gulu Hospital Kibaale Lacor Hospital Abim Kagadi General Hospital Moroto Surgeon Repair Skill Status Dr. Steven B. Mayanja Simple Active qÆ Zombo Nwoya qÆ Nebbi Otuke Moroto Hospital Nebbi Hospital Napak Kabarole Oyam Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital Kole Lira Surgeon Repair Skill Status qÆ Alebtong Dr. Abirileku Lawrence Simple Active Lira Hospital Limited Amuria Dr. Charles Kimera Training Inactive Kiryandongo 2°0'0"N 2°0'0"N Virika General Hospital Bullisa Amudat HospitalqÆ Apac Dokolo Katakwi Dr. Priscilla Busingye Simple Inactive Nakapiripirit Amudat Kasese Kaberamaido Soroti Kagando General Hospital Masindi qÆ Soroti Hospital Surgeon Repair Skill Status Amolatar Dr. Frank Asiimwe Complex Visiting qÆ Kumi Hospital Dr. Asa Ahimbisibwe Intermediate Visiting Serere Ngora Kumi Bulambuli Kween Dr. -

Office of the Auditor General

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ANNUAL REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2014 VOLUME 2 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms And Abreviations ................................................................................................ viii 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Report And Opinion Of The Auditor General On The Government Of Uganda Consolidated Financial Statements For The Year Ended 30th June, 2014 ....................... 38 Accountability Sector................................................................................................................... 55 3.0 Treasury Operations .......................................................................................................... 55 4.0 Ministry Of Finance, Planning And Economic Development ............................................. 62 5.0 Department Of Ethics And Integrity ................................................................................... 87 Works And Transport Sector ...................................................................................................... 90 6.0 Ministry Of Works And Transport ....................................................................................... 90 Justice Law And Order Sector .................................................................................................. 120 7.0 Ministry Of Justice And Constitutional -

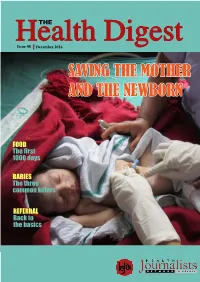

Saving the Mother and the Newborn

THE HealthIssue 08 December 2016 Digest SAVING THE MOTHER AND THE NEWBORN FOOD The first 1000 days BABIES The three common killers REFERRAL Back to the basics Inside this issue 1. Table of contents ....................................................................................................................... Page 1 2. Message from the editor .......................................................................................................... Page 2 3. Letter from Save the Children ........................................................................................................ Page 3 4. What does the mirror say? ............................................................................................................... Page 4 5. The three common baby killers ............................................................................................ Page 15 6. Good feeding generates good baby health .............................................................................. Page 18 7. We need a stronger referral system ............................................................................................. Page 21 8. Saving Uganda’s mothers and newborns ....................................................................................... Page 24 9. Customer care at hospitals .............................................................................................................. Page 26 10. Hard to reach: Busanza in Kisoro .......................................................................................... -

Health Sector Ministerial Policy Statement

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA HEALTH SECTOR MINISTERIAL POLICY STATEMENT MINISTERIAL POLICY STATEMENT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 MINISTRY OF HEALTH PLOT 6, LOURDEL ROAD, NAKASERO P.O.BOX 7272, KAMPALA www.health.go.ug BY DR. JANE RUTH ACENG, THE HON. MINISTER OF HEALTH FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA HEALTH SECTOR MINISTERIAL POLICY STATEMENT BY DR. JANE RUTH ACENG THE HON. MINISTER OF HEALTH, FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA HEALTH SECTOR MINISTERIAL POLICY STATEMENT BY DR. JANE RUTH ACENG THE HON. MINISTER OF HEALTH, FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 Health Ministerial Policy Statement for FY 2020/21 1 PB 1 Ministerial Policy Statement FY 2020/21 Abbreviations and Acronyms ABC Abstinence, Be faithful and use Condoms ACP AIDS Control Programme ACT Artemisinin Combination Therapies ADB African Development Bank AFP Acute Flaccid Paralysis AHSPR Annual Health Sector Performance Report AI Avian Influenza AIDS Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome AIM AIDS Integrated Management AMREF African Medical Research Foundation ANC Ante Natal Care ARC Alliance for Rabies Control ARCC African Regional Certification Commission ART Anti Retroviral Therapy ARVs Antiretroviral Drugs AT Area Team AWP Annual Work Plan AZT Azidothymidine BCC Behavioural Change and Communication BEmOC Basic Emergency Obstetric Care BFP Budget Framework Paper BOP Best Operational Practices CAP Consolidated Appeal Process CB-DOTS Community Based TB Directly Observed Treatment CBDS Community Based -

Research Report No. 1 GOVERNING HEALTH

Research Report No. 1 GOVERNING HEALTH SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA: A TRACKING STUDY OF DRUG DELIVERY MECHANISMS RESEARCH REPORT BY ECONOMIC POLICY RESEARCH CENTRE JANUARY 2010 Abbreviations/Acronyms AG Auditor General ART Anti Retroviral Treatment ARVs Anti-Retroviral Drugs bn Billion CAO Chief Administrative Officer CIPLA Chemical, Industries and Pharmaceutical Laboratories CMS Central Medical Stores DHO District Health Officer DHT District Health Team FGDs Focus Group Discussions FY Financial Year GoU Government of Uganda HMIS Health Management Information System HSC Health Service Commission HSD Health Sub-District HSSP Health Sector Strategic Plan HUMC Health Unit Management Committee JMS Joint Medical Stores Km Kilometre LoGs Local Governments m Million MO Medical Officer MoFPED Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development MoH Ministry of Health MoLG Ministry of Local Government MoPS Ministry of Public Service MP Member of Parliament MS Medical Superintendent MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework NCDs Non-Communicable diseases NDA National Drug Authority NDP Nation Development Plan NGO Non-Government Organisation NMS National Medical Stores OPD Out Patient Department ORS Oral Rehydration Solutions PAC Public Accounts Committee PEAP Poverty Eradication Alleviation Plan PETS Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys PHC Primary Health Care i PNFP Private Not-for-Profit PPPs Public-Private Partnerships QCIL Quality Chemical Industries Limited RDC Resident District Commissioner RDTs Rapid Diagnostic Tests RTI Respiratory Tract Infections TBA Traditional Birth Attendant TRIPS Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights UBoS Uganda Bureau of Statistics UCMB Uganda Catholic Medical Bureau UJAS Uganda Joint Assistance Strategy Ushs Uganda Shillings UNMHCP Uganda National Minimum Health Care Package UPMB Uganda Protestant Medical Bureau WTO World Trade Organisation US$ United Stated Dollars WHO World Health Organisation ii Table of Contents 1. -

Incidence and Predictors of Two Months' Sputum Non Follow-Up And

Apolo Ayebale 2020 ISSN 2573-0320 Vol.04 No.3 Incidence and predictors of two months’ sputum non follow-up and patients’ perceived quality of care, Hoima district Apolo Ayebale Makerere University, Uganda Introduction: The World Health Organization and Ministry of health recommend monitoring of discussions were held among tuberculosis patients tuberculosis patients on treatment for progress. initiated on treatment from 1st October 2018 to 31st Provision of sufficiently high tuberculosis care January 2019,one in Hoima hospital and Kigorobya quality is necessary to achieve the end tuberculosis health center IV. strategy. However there is limited data on providers’ Results: The incidence of two months’ sputum non adherence to these policies. Tuberculosis treatment follow- up was 26.9% (95%CI = 7.0 – 64.4). The success in Hoima district was only 68% in 2017 predictors associated with sputum non follow-up compared to the national target of 85%. About 55% include positive versus negative HIV status(aIRR = of the smear positive tuberculosis patients remain 1.48, P<0.001), not on versus being on directly positive at the end of two months of medication. observed treatment (aIRR= 1.31 P=0.002), rural Two month sputum non follow-up reduces chances versus urban health facilities of early detection of treatment failure. (aIRR=1.79, P=0.006), private versus government Objective: The main objective was to determine health facilities (aIRR=2.05, P=0.015), distance the incidence, predictors of two months’ sputum >5km versus ≤5km (aIRR = 1.38, P = 0.021), non follow-up and explore patients’ perceived Baseline tuberculosis drug sensitivity (aIRR = 1.44, quality of care among pulmonary tuberculosis P= 0.318) confounded health facility location. -

Office of the President

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ANNUAL REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2007 VOLUME 2 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 1 GENERAL OBSERVATIONS .................................................................. 5 REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON GOVERNMENT OF UGANDA CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ............................................. 29 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT ............................................................... 42 STATE HOUSE ............................................................................... 44 OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER ........................................................ 47 PUBLIC SERVICE ............................................................................ 57 FOREIGN AFFAIRS .......................................................................... 59 JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS .............................................. 66 FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ............................... 71 AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL INDUSTRY AND FISHERIES .................................. 77 LANDS, HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT ........................................ 93 WATER AND ENVIRONMENT ............................................................ 101 EDUCATION AND SPORTS ............................................................... 119 HEALTH 140 WORKS AND TRANSPORT ............................................................... 152 DEFENCE …………………........................................................................... -

Names of Societiesregistered on Probation Probation Akwata Empola Hides & Skins Probation Kweyo Growers Cooperative Society

NAMES OF SOCIETIESREGISTERED ON PROBATION PROBATION AKWATA EMPOLA HIDES & SKINS PROBATION KWEYO GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION OPWODI GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION PUGODA GUDA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION KATIMBA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION NKUNGULATE GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION WOBUTUNGULU GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION GAYA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION RUGARAMA TWEHEYO GROWERS COOPERATIVE SAVING AND CREDIT SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION DAWAINO GROWERS COOPERATIVE SAVING AND CREDIT SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION KAKUBASIRI GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION RWEIKINIRO GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION PUMIT GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION BUSAGAZI GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION AENTOLIM GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION KARENGA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION PAJULE TOBACCO GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION KABUMBUZI GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION BIVAMUNKUMBI GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION SEMBWA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION BULYASI GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION BUGUNDA BUGULA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION BAKUSEKA MAGENDA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION MWENGE ENGULI DISTILLERS PROBATION KIJAGUZO GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION NAMULAMBA ANIYALIAMANYI PROBATION LUUMA GROWERS COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED PROBATION ANYARA IKAKORIOT GROWERS -

Kingfisher Oil Development Public Participation

September 2018 CNOOC UGANDA LIMITED Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the CNOOC Uganda Ltd Kingfisher Oil Project in Hoima District, Uganda - Public Participation Report Submitted to: The Executive Director National Environment Management Authority NEMA House, Plot 17/19/21 Jinja Road, P. O. Box 22255 Kampala, Uganda Report Number: 1776816-319401-4 REPORT – VOLUME 1, APPENDIX 2 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION FOR ESIA, PROPOSED KINGFISHER PROJECT Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS, GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS ...................................................................... 2 3.0 OBJECTIVES OF PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN AN ESIA ......................................................................................... 2 4.0 STAKEHOLDERS ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 5.0 CNOOC ENGAGEMENT WITH STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................... 6 6.0 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION FOR SCOPING .................................................................................................................. 8 6.1 Announcements ............................................................................................................................................. 14 6.2 Materials ........................................................................................................................................................ -

A History of Bunyoro-Kitara

EAST AFRICAN STUDIES 19 A HISTORY OF BUNYORO-KITARA A. R. Dunbar INSTITUTE OP 30C|ftL EAST AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL RESEARCH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1. R. A. Sir Tito Winyi, C.B.E., Omukama of Bunyoro-Kitara. A. R. DUNBAR M.A., Dip. Agric. (Cantab.), D. T. A. (TRIN.) Published on behalf of The East African Institute of Social Research by m OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS NAIROBI 1965 Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E.C. 4 GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA CAPE TOWN SALISBURY NAIROBI IBADAN ACCRA KUALA LUMPUR HONG KONG © East African Institute of Social Research 1965 FOREWORD By R.A. Sir Tito Winyi, C.B.E., Omukama of Bunyoro-Kitara I AM indebted to the writer of this book for giving me the opportunity of writing a foreword to it. The book briefly tackles the history of the ancient kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara from which all conceptions of kingship in Uganda originated. The book has been written during the time in which I have been the King ruling in the succession of my ancestors. Kitara was a kingdom of vast size stretching from Tanganyika to Lake Rudolf and from Lake Naivasha to the Ituri Forest in the Congo. Through unfavourable and unjustifiable circumstances the kingdom was reduced by the British to its present extent. Part was made into a separate kingdom, Toro, part was given to the former Belgian Congo and part was entrusted to Buganda—hence our 'Lost Counties'. In spite of being small the kingdom still retains its cultural pride and traditions and at the same time cherishes its unquenchable spirit of regaining its 'Lost Counties'.