Highlights from the Plaster Cast Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page Introduction Trojan Cycle: Cypria Iliad (Synopsis) Aethiopis Little Iliad Sack of Ilium Returns Odyssey (Synopsis) Telegony Other works on the Trojan War Bibliography Introduction and Definition of terms The so called Epic Cycle is sometimes referred to with the term Epic Fragments since just fragments is all that remain of them. Some of these fragments contain details about the Theban wars (the war of the SEVEN and that of the EPIGONI), others about the prowesses of Heracles 1 and Theseus, others about the origin of the gods, and still others about events related to the Trojan War. The latter, called Trojan Cycle, narrate events that occurred before the war (Cypria), during the war (Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Ilium ), and after the war (Returns, and Telegony). The term epic (derived from Greek épos = word, song) is generally applied to narrative poems which describe the deeds of heroes in war, an astounding process of mutual destruction that periodically and frequently affects mankind. This kind of poetry was composed in early times, being chanted by minstrels during the 'Dark Ages'—before 800 BC—and later written down during the Archaic period— from c. 700 BC). Greek Epic is the earliest surviving form of Greek (and therefore "Western") literature, and precedes lyric poetry, elegy, drama, history, philosophy, mythography, etc. -

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology (2007)

P1: JzG 9780521845205pre CUFX147/Woodard 978 0521845205 Printer: cupusbw July 28, 2007 1:25 The Cambridge Companion to GREEK MYTHOLOGY S The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology presents a comprehensive and integrated treatment of ancient Greek mythic tradition. Divided into three sections, the work consists of sixteen original articles authored by an ensemble of some of the world’s most distinguished scholars of classical mythology. Part I provides readers with an examination of the forms and uses of myth in Greek oral and written literature from the epic poetry of the eighth century BC to the mythographic catalogs of the early centuries AD. Part II looks at the relationship between myth, religion, art, and politics among the Greeks and at the Roman appropriation of Greek mythic tradition. The reception of Greek myth from the Middle Ages to modernity, in literature, feminist scholarship, and cinema, rounds out the work in Part III. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology is a unique resource that will be of interest and value not only to undergraduate and graduate students and professional scholars, but also to anyone interested in the myths of the ancient Greeks and their impact on western tradition. Roger D. Woodard is the Andrew V.V.Raymond Professor of the Clas- sics and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Buffalo (The State University of New York).He has taught in the United States and Europe and is the author of a number of books on myth and ancient civiliza- tion, most recently Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. Dr. -

MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy After Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda

HOMESCHOOL THIRD THURSDAYS MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy after Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda Workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (Italian), 1602-03. Oil on canvas. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Creature Creation Today, we challenge you to create your own mythological creature out of Crayola’s Model Magic! Open your packet of Model Magic and begin creating. If you need inspiration, take a look at the back of this sheet. MYTHOLOGICAL Try to incorporate basic features of animals – eyes, mouths, legs, etc.- while also combining part of CREATURES different creatures. Some works of art that we are featuring for Once you’ve finished sculpting, today’s Homeschool Third Thursday include come up with a unique name for creatures like the sea monster. Many of these your creature. Does your creature mythological creatures consist of various human have any special powers or and animal parts combined into a single creature- abilities? for example, a centaur has the body of a horse and the torso of a man. Other times the creatures come entirely from the imagination, like the sea monster shown above. Some of these creatures also have supernatural powers, some good and some evil. Mythological Creatures: Continued Greco-Roman mythology features many types of mythological creatures. Here are some ideas to get your project started! Sphinxes are wise, riddle- loving creatures with bodies of lions and heads of women. Greek hero Perseus rides a flying horse named Pegasus. Sphinx Centaurs are Greco- Pegasus Roman mythological creatures with torsos of men and legs of horses. Satyrs are creatures with the torsos of men and the legs of goats. -

The Metopes of Temple C

Taming Women and Making Men at Thermon: The Metopes of Temple C Temple C at Thermon in Aitolia is among the earliest Greek temples to display an elaborate program of figural decoration. This included mold-made terracottas shaped like the heads of women and lions, as well as—more unusually for this period—metopes painted in the style of contemporary Corinthian pottery. Although the surviving metopes are poorly preserved, several bear recognizable subjects (Antonetti 1990: 173-185). A few show beasts, including a gorgoneion, a lion, and possibly a sphinx, while several more show episodes identifiable from myth. These include Perseus fleeing a gorgon, Aedon and Khelidon murdering Itys, a hunter (possibly Meleager, Orion, or a local hero) returning from the hunt, and two seminude women who have been plausibly identified as Proitides. Finally, a metope showing a seated triad (either a group of goddesses or the Letoids) dates to the temple’s Hellenistic restoration (Stucky 1988), although it is painted in the Archaic style and may reproduce the subject of an earlier metope (Anguissola 2007). Temple decoration from elsewhere in the Archaic Greek world provides a context for understanding the beasts and repeated frontal faces of Temple C: as Marconi has argued, such figures would instill in the worshipper the awe and terror that encounters with the sacred demanded (2004: 221-222). The metopes with narrative content, however, present greater interpretive challenges. Their poor state of preservation, the paucity of contemporary local comparanda, and our uncertainty about the identity of the deity to whom the early temple belonged have made it difficult to determine why these themes were represented together or what suited them to this site. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

A Collection of Curricula for the STARLAB Greek Mythology Cylinder

A Collection of Curricula for the STARLAB Greek Mythology Cylinder Including: A Look at the Greek Mythology Cylinder Three Activities: Constellation Creations, Create a Myth, I'm Getting Dizzy by Gary D. Kratzer ©2008 by Science First/STARLAB, 95 Botsford Place, Buffalo, NY 14216. www.starlab.com. All rights reserved. Curriculum Guide Contents A Look at the Greek Mythology Cylinder ...................3 Leo, the Lion .....................................................9 Introduction ......................................................3 Lepus, the Hare .................................................9 Andromeda ......................................................3 Libra, the Scales ................................................9 Aquarius ..........................................................3 Lyra, the Lyre ...................................................10 Aquila, the Eagle ..............................................3 Ophuichus, Serpent Holder ..............................10 Aries, the Ram ..................................................3 Orion, the Hunter ............................................10 Auriga .............................................................4 Pegasus, the Winged Horse..............................11 Bootes ..............................................................4 Perseus, the Champion .....................................11 Cancer, the Crab ..............................................4 Phoenix ..........................................................11 Canis Major, the Big Dog -

Thinking Comparatively About Greek Mythology V, Reconstructing He#Rakle#S Forward in Time

Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology V, Reconstructing He#rakle#s forward in time The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2019.08.22. "Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology V, Reconstructing He#rakle#s forward in time." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thinking-comparatively- about-greek-mythology-v-reconstructing-herakles-forward-in- time/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42179085 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. -

AND DID THOSE HOOVES Pan and the Edwardians

1 AND DID THOSE HOOVES Pan and the Edwardians By Eleanor Toland A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2014 2 “….a goat’s call trembled from nowhere to nowhere…” James Stephens, The Crock of Gold, 1912 3 Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………..5 Introduction: Pan and the Edwardians………………………………………………………….6 Chapter One: Pan as a Christ Figure, Christ as a Pan Figure…………………………………...17 Chapter Two: Uneasy Dreams…………………………………………..…………………......28 Chapter Three: Savage Wildness to Garden God………….…………………………………...38 Chapter Four: Culminations….................................................................................................................48 Chapter Five: The Prayer of the Flowers………………...…………………………………… 59 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………….70 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………...73 4 Acknowledgements My thanks to Lilja, Lujan, Saskia, Thomas, Emily, Eve, Mehdy, Eden, Margie, Katie, Anna P, the other Anna P, Hannah, Sarah, Caoilinn, Ronan, Kay, Angelina, Iain et Alana and anyone else from the eighth and ninth floor of the von Zedlitz building who has supplied a friendly face or a kind word. Your friendship and encouragement has been a fairy light leading me out of a perilous swamp. Thank you to my supervisors, Charles and Geoff, without whose infinite patience and mentorship this thesis would never have been finished, and whose supervision went far beyond the call of duty. Finally, thank you to my family for their constant support and encouragement. 5 Abstract A surprisingly high number of the novels, short stories and plays produced in Britain during the Edwardian era (defined in the terms of this thesis as the period of time between 1900 and the beginning of World War One) use the Grecian deity Pan, god of shepherds, as a literary motif. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

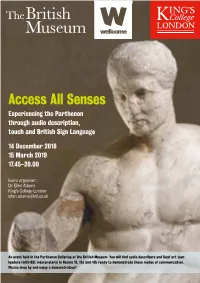

Access All Senses Experiencing the Parthenon Through Audio Description, Touch and British Sign Language

Access All Senses Experiencing the Parthenon through audio description, touch and British Sign Language 14 December 2018 15 March 2019 17.45–20.00 Event organiser: Dr Ellen Adams King’s College London [email protected] An event held in the Parthenon Galleries of the British Museum. You will find audio describers and Deaf art tour leaders (with BSL interpreters) in Rooms 18, 18a and 18b ready to demonstrate these modes of communication. Please drop by and enjoy a demonstration!’ The Parthenon Galleries of the British Museum The Parthenon’s sculptural programme Drawn by Ellen Adams (Blue: frieze; Green: pediments; Red: metopes) The Parthenon was constructed in the fifth century BC on the Athenian Acropolis. One of the most impressive monuments from the ancient world, it possessed an Drawn by Ellen Adams elaborate and sophisticated sculptural programme, which celebrated Greek We may compare this layout with the original sculptural programme (see across). (or Athenian) greatness. page 2 page 3 What is Audio Description (AD)? What is British Sign Language (BSL)? AD provides access for blind or partially sighted (BPS) people, by using words to Sign languages are not simply manual versions of the local spoken language. create vivid visions and sensory experiences in the mind. Most BPS people can see BSL has a clear set of grammatical rules based on entirely different criteria from something – shapes, colours, or tunnel-vision. Spoken language can help make sense spoken English. There are estimated to be 50,000-70,000 people in the UK who state of this partial information. AD is a practice-led activity, and is studied and taught in BSL as their preferred language. -

1 the Curse of Minerva

1 The Curse of Minerva edited by Peter Cochran The Marbles would have gone in the vertically-lined section beneath the upper part. Built between 447 and 432 BC, the Parthenon symbolises, not Greek civilisation, so much as Athenian political hegemony over the rest of Greece (which the Athenians would have said was the same thing). It is a statement of imperialist triumph. The metopes around its border symbolise (or symbolised) the triumph of Athenian order over barbarian chaos: battles against the Amazons, between the Lapiths and the Centaurs, between the Gods and the Giants, and between the Greeks and the Trojans. Athens in Byron’s day In Byron’s time Athens was technically the fiefdom one of the Black Eunuchs at Constantinople, 1 and neither the town nor its archaeological treasures was much valued by either its Greek inhabitants or its Turkish rulers; though Byron does record in a note to Childe Harold II that as Lord Elgin’s servants lifted yet another marble from the building, a Turkish officer witnessing the depredation wept, and said “enough!”. This observation was made not by Byron, but by his friend Edward Daniel Clarke, and Byron put it into later editions. 2 By the time Lord Elgin and Byron arrived in Greece, the building was in an advanced state of decay. A major disaster had occurred in 1687, when the Venetian general Francesco Morosini besieged the place, and, knowing that the Turks had gunpowder stored in it, 1: See The Giaour , 151, Byron’s note. 2: See CHP II stanzas 11-14, and Byron’s prose notes, for more thoughts about the marbles.