The Potential of Type Species to Destabilise the Taxonomy of Zooxanthellate Scleractinia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

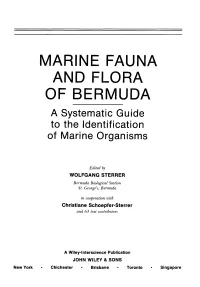

MARINE FAUNA and FLORA of BERMUDA a Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms

MARINE FAUNA AND FLORA OF BERMUDA A Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms Edited by WOLFGANG STERRER Bermuda Biological Station St. George's, Bermuda in cooperation with Christiane Schoepfer-Sterrer and 63 text contributors A Wiley-Interscience Publication JOHN WILEY & SONS New York Chichester Brisbane Toronto Singapore ANTHOZOA 159 sucker) on the exumbrella. Color vari many Actiniaria and Ceriantharia can able, mostly greenish gray-blue, the move if exposed to unfavorable condi greenish color due to zooxanthellae tions. Actiniaria can creep along on their embedded in the mesoglea. Polyp pedal discs at 8-10 cm/hr, pull themselves slender; strobilation of the monodisc by their tentacles, move by peristalsis type. Medusae are found, upside through loose sediment, float in currents, down and usually in large congrega and even swim by coordinated tentacular tions, on the muddy bottoms of in motion. shore bays and ponds. Both subclasses are represented in Ber W. STERRER muda. Because the orders are so diverse morphologically, they are often discussed separately. In some classifications the an Class Anthozoa (Corals, anemones) thozoan orders are grouped into 3 (not the 2 considered here) subclasses, splitting off CHARACTERISTICS: Exclusively polypoid, sol the Ceriantharia and Antipatharia into a itary or colonial eNIDARIA. Oral end ex separate subclass, the Ceriantipatharia. panded into oral disc which bears the mouth and Corallimorpharia are sometimes consid one or more rings of hollow tentacles. ered a suborder of Scleractinia. Approxi Stomodeum well developed, often with 1 or 2 mately 6,500 species of Anthozoa are siphonoglyphs. Gastrovascular cavity compart known. Of 93 species reported from Ber mentalized by radially arranged mesenteries. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Genetic Structure Is Stronger Across Human-Impacted Habitats Than Among Islands in the Coral Porites Lobata

Genetic structure is stronger across human-impacted habitats than among islands in the coral Porites lobata Kaho H. Tisthammer1,2, Zac H. Forsman3, Robert J. Toonen3 and Robert H. Richmond1 1 Kewalo Marine Laboratory, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, United States of America 2 Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, United States of America 3 Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Kaneohe, HI, United States of America ABSTRACT We examined genetic structure in the lobe coral Porites lobata among pairs of highly variable and high-stress nearshore sites and adjacent less variable and less impacted offshore sites on the islands of O‘ahu and Maui, Hawai‘i. Using an analysis of molecular variance framework, we tested whether populations were more structured by geographic distance or environmental extremes. The genetic patterns we observed followed isolation by environment, where nearshore and adjacent offshore populations showed significant genetic structure at both locations (AMOVA FST D 0.04∼0.19, P < 0:001), but no significant isolation by distance between islands. Strikingly, corals from the two nearshore sites with higher levels of environmental stressors on different islands over 100 km apart with similar environmentally stressful conditions were genetically closer (FST D 0.0, P D 0.73) than those within a single location less than 2 km apart (FST D 0.04∼0.08, P < 0:01). In contrast, a third site with a less impacted nearshore site (i.e., less pronounced environmental gradient) showed no significant structure from the offshore comparison. Our results show much stronger support for environment than distance separating these populations. -

Review on Hard Coral Recruitment (Cnidaria: Scleractinia) in Colombia

Universitas Scientiarum, 2011, Vol. 16 N° 3: 200-218 Disponible en línea en: www.javeriana.edu.co/universitas_scientiarum 2011, Vol. 16 N° 3: 200-218 SICI: 2027-1352(201109/12)16:3<200:RHCRCSIC>2.0.TS;2-W Invited review Review on hard coral recruitment (Cnidaria: Scleractinia) in Colombia Alberto Acosta1, Luisa F. Dueñas2, Valeria Pizarro3 1 Unidad de Ecología y Sistemática, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, D.C., Colombia. 2 Laboratorio de Biología Molecular Marina - BIOMMAR, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, D.C., Colombia. 3 Programa de Biología Marina, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano. Santa Marta. Colombia. * [email protected] Recibido: 28-02-2011; Aceptado: 11-05-2011 Abstract Recruitment, defined and measured as the incorporation of new individuals (i.e. coral juveniles) into a population, is a fundamental process for ecologists, evolutionists and conservationists due to its direct effect on population structure and function. Because most coral populations are self-feeding, a breakdown in recruitment would lead to local extinction. Recruitment indirectly affects both renewal and maintenance of existing and future coral communities, coral reef biodiversity (bottom-up effect) and therefore coral reef resilience. This process has been used as an indirect measure of individual reproductive success (fitness) and is the final stage of larval dispersal leading to population connectivity. As a result, recruitment has been proposed as an indicator of coral-reef health in marine protected areas, as well as a central aspect of the decision-making process concerning management and conservation. -

Biology Assessment Plan Spring 2019

Biological Sciences Department 1 Biology Assessment Plan Spring 2019 Task: Revise the Biology Program Assessment plans with the goal of developing a sustainable continuous improvement plan. In order to revise the program assessment plan, we have been asked by the university assessment committee to revise our Students Learning Outcomes (SLOs) and Program Learning Outcomes (PLOs). Proposed revisions Approach: A large community of biology educators have converged on a set of core biological concepts with five core concepts that all biology majors should master by graduation, namely 1) evolution; 2) structure and function; 3) information flow, exchange, and storage; 4) pathways and transformations of energy and matter; and (5) systems (Vision and Change, AAAS, 2011). Aligning our student learning and program goals with Vision and Change (V&C) provides many advantages. For example, the V&C community has recently published a programmatic assessment to measure student understanding of vision and change core concepts across general biology programs (Couch et al. 2019). They have also carefully outlined student learning conceptual elements (see Appendix A). Using the proposed assessment will allow us to compare our student learning profiles to those of similar institutions across the country. Revised Student Learning Objectives SLO 1. Students will demonstrate an understanding of core concepts spanning scales from molecules to ecosystems, by analyzing biological scenarios and data from scientific studies. Students will correctly identify and explain the core biological concepts involved relative to: biological evolution, structure and function, information flow, exchange, and storage, the pathways and transformations of energy and matter, and biological systems. More detailed statements of the conceptual elements students need to master are presented in appendix A. -

Zootaxa, Type Specimens, Samples of Live Individuals and the Galapagos

Zootaxa 2201: 12–20 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Editorial ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Type specimens, samples of live individuals and the Galapagos Pink Land Iguana THOMAS M. DONEGAN 1 1 Fundación ProAves, 33 Blenheim Road, Caversham, Reading, RG4 7RT, UK [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract The nomenclatural implications of Gentile & Snell (2009)'s innovations in the designation of a type specimen - that is sampled and tagged but not killed - are discussed. The paper also responds to Nemésio (2009)'s criticism of Donegan (2008), where I argued that descriptions based on samples of live individuals are valid. I also discuss whether recent descriptions of such a nature involve a different degree of scientific rigour to other descriptions. Key words: Nomenclatural availability, vouchers, collecting, specimen, type specimen, sample, ethics, framework, Code, Commission, Conolophus marthae. Introduction In this issue of Zootaxa, Gentile & Snell (2009) describe a critically endangered new species of land iguana from the Gálapagos islands, named Conolophus marthae. Aside from being an important discovery, this description includes noteworthy innovations in the designation of a type specimen based on a live individual. In a recent exchange of papers in Zootaxa, the validity of descriptions based on a holotype which is not a full, dead specimen (such as this) have been discussed (Dubois & Nemésio 2007, Donegan 2008, Nemésio 2009). Dubois and Nemésio have expressed the viewpoint that descriptions based on live individuals are not valid nomenclatural acts. I have expressed the contrary view. Other recent descriptions based on holotypes which are not killed have relied solely upon photographs and, in some instances, samples taken from live individuals (see discussion in Donegan 2008). -

Taxonomy and Phylogenetic Relationships of the Coral Genera Australomussa and Parascolymia (Scleractinia, Lobophylliidae)

Contributions to Zoology, 83 (3) 195-215 (2014) Taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships of the coral genera Australomussa and Parascolymia (Scleractinia, Lobophylliidae) Roberto Arrigoni1, 7, Zoe T. Richards2, Chaolun Allen Chen3, 4, Andrew H. Baird5, Francesca Benzoni1, 6 1 Dept. of Biotechnology and Biosciences, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20126, Milan, Italy 2 Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum, 49 Kew Street, Welshpool, WA 6106, Australia 3Biodiversity Research Centre, Academia Sinica, Nangang, Taipei 115, Taiwan 4 Institute of Oceanography, National Taiwan University, Taipei 106, Taiwan 5 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD 4811, Australia 6 Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, UMR227 Coreus2, 101 Promenade Roger Laroque, BP A5, 98848 Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia 7 E-mail: [email protected] Key words: COI, evolution, histone H3, Lobophyllia, Pacific Ocean, rDNA, Symphyllia, systematics, taxonomic revision Abstract Molecular phylogeny of P. rowleyensis and P. vitiensis . 209 Utility of the examined molecular markers ....................... 209 Novel micromorphological characters in combination with mo- Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 210 lecular studies have led to an extensive revision of the taxonomy References ...................................................................................... 210 and systematics of scleractinian corals. In the present work, we Appendix ....................................................................................... -

Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Scott and Seringapatam Reef Western Australia 2006 Edited by Clay Bryce

ISBN 978-1-920843-50-2 ISSN 0313 122X Scott and Seringapatam Reef. Western Australia Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Scott and Seringapatam Reef Western Australia 2006 2006 Edited by Clay Bryce Edited by Clay Bryce Suppl. No. Records of the Western Australian Museum 77 Supplement No. 77 Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 77 Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Scott and Seringapatam Reef Western Australia 2006 Edited by Clay Bryce Records of the Western Australian Museum The Records of the Western Australian Museum publishes the results of research into all branches of natural sciences and social and cultural history, primarily based on the collections of the Western Australian Museum and on research carried out by its staff members. Collections and research at the Western Australian Museum are centred on Earth and Planetary Sciences, Zoology, Anthropology and History. In particular the following areas are covered: systematics, ecology, biogeography and evolution of living and fossil organisms; mineralogy; meteoritics; anthropology and archaeology; history; maritime archaeology; and conservation. Western Australian Museum Perth Cultural Centre, James Street, Perth, Western Australia, 6000 Mail: Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986 Telephone: (08) 9212 3700 Facsimile: (08) 9212 3882 Email: [email protected] Minister for Culture and The Arts The Hon. John Day BSc, BDSc, MLA Chair of Trustees Mr Tim Ungar BEc, MAICD, FAIM Acting Executive Director Ms Diana Jones MSc, BSc, Dip.Ed Editors Dr Mark Harvey BSC, PhD Dr Paul Doughty BSc(Hons), PhD Editorial Board Dr Alex Baynes MA, PhD Dr Alex Bevan BSc(Hons), PhD Ms Ann Delroy BA(Hons), MPhil Dr Bill Humphreys BSc(Hons), PhD Dr Moya Smith BA(Hons), Dip.Ed. -

Note on the Sauropod and Theropod Dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Madagascar*

EXTRACT FROM THE BULLETIN DE LA SOCIÉTÉ GÉOLOGIQUE DE FRANCE 3rd series, volume XXIV, page 176, 1896. NOTE ON THE SAUROPOD AND THEROPOD DINOSAURS FROM THE UPPER CRETACEOUS OF MADAGASCAR* by Charles DEPÉRET. (PLATE VI). Translated by Matthew Carrano Department of Anatomical Sciences SUNY at Stony Brook, September 1999 The bones of large dinosaurian reptiles described in this work were brought to me by my good friend, Mr. Dr. Félix Salètes, primary physician for the Madagascar expedition, from the environs of Maevarana, where he was charged with installing a provisional hospital. This locality is situated on the right bank of the eastern arm of the Betsiboka, 46 kilometers south of Majunga, on the northwest coast of the island of Madagascar. Not having the time to occupy himself with paleontological studies, Dr. Salètes charged one of his auxiliary agents, Mr. Landillon, company sergeant-major of the marines, with researching the fossils in the environs of the Maevarana post. Thanks to the zeal and activity of Mr. Landillon, who was not afraid to gravely expose his health in these researches, I have been able to receive the precious bones of terrestrial reptiles that are the object of this note, along with an important series of fossil marine shells. I eagerly seize the opportunity here to thank Mr. Landillon for his important shipment and for the very precise geological data which he communicated to me concerning the environs of Maevarana, and of which I will now give a short sketch. 1st. Geology of Maevarana and placement of the localities. * Original reference: Depéret, C. -

Transfer of the Type Species of the Genus Themobacteroides to the Genus Themoanaerobacter As Themoanaerobacter Acetoethylicus (Ben-Bassat and Zeikus 1981) Comb

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SYSTEMATICBACTERIOLOGY, Oct. 1993, p. 857-859 Vol. 43, No. 4 0020-7713/93/040857-03$02.00/0 Copyright 0 1993, International Union of Microbiological Societies Transfer of the Type Species of the Genus Themobacteroides to the Genus Themoanaerobacter as Themoanaerobacter acetoethylicus (Ben-Bassat and Zeikus 1981) comb. nov., Description of Coprothemobacter gen. nov., and Reclassification of Themobacteroides proteolyticus as Coprothennobacter proteolyticus (Ollivier et al. 1985) comb. nov. FRED A. RAINEY AND ERKO STACKEBRANDT* DSM-Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroolganisrnen und Zellkulturen, Mascheroder Weg lb, 38124 Braunschweig, Germany Phylogenetic and phenotypic evidence demonstrates the taxonomic heterogeneity of the genus Thennobac- teroides and indicates a close relationship between Thennobacteroides acetoethylicus and members of the genus Thennoanaerobacter. Since T. acetoethylicus is the type species of Thennobacteroides, its removal invalidates the genus. As a consequence, the remaining species Thennobacteroides proteolyticus is proposed as the type species of the new genus Coprothennobacter gen. nov., as Coprothennobacter proteolyticus comb. nov. Recent phylogenetic studies (8, 9) of anaerobic thermo- hybridization studies with all members of Thermoanaero- philic species demonstrated that the majority of strains fall bacter (6, 10) despite the fact that, like Thermoanaerobacter within the phylogenetic confines of the Clostridium-Bacillus species, Thermobacteroides acetoethylicus is an anaerobic, subphylum of gram-positive bacteria. In contrast to the thermophilic, glycolytic bacterium capable of growth above phylog enet ically coherent genera Thermoana erobac ter (6) 70°C that has been isolated from geothermal environments. and Thermoanaerobacterium (6), members of Thermobac- The reclassifications of the recent study of Lee et al. (6) teroides (1,7) belonged to phylogenetically very diverse taxa increased the numbers of species of Thermoanaerobacter to (8). -

Introduction to Botany

Introduction to Botany Jan Zientek Senior Program Coordinator Cooperative Extension of Essex County [email protected] Basic Botany • The study of the growth, structure and function of plants Plant Functions BOTANY • Evolution • Taxonomy • Plant morphology • Plant physiology and cell biology • Plant reproduction • Plant hormones and growth regulators PLANTAE • Eukaryotic (with a • Chloroplasts nucleus) (green) • Cell walls with • Non-motile cellulose • Several phlyum • Food stored as • Development of carbohydrate pollen • Multi-cellular autotrophs DOMAIN KINGDOM PHYLUM CLASS ORDER FAMILY Genus species Plant phylums Mosses Cycads Liverworts Ginkgoes Hornworts Gnetophytes Club mosses Conifers Horsetails Ferns Common Name vs Scientific Name Foxglove Digitalis purpurea • Maybe local name • Universally recognized • General • Specific Common Name vs Scientific Name Fire bush Scarlet bush Texas firecracker Corail (or is it Koray?) Hamelia patens Polly red head Hummingbird bush Ix-canan Plant Types • Monocots: have a single cotyledon, flower parts in multiples of three, parallel venation of leaves, scattered vascular bundles in stems. Dicots: have two cotyledons, flower parts in multiples of 4 or 5, netted veins, and stems which are organized in a ring pattern. Humans sort things many different ways • Plants can be classified by the type of their seed structure – Gymnosperm: “naked seed” – Angiosperm: seed within a fruiting body • Lifecycles help gardeners distinguish between plants: • Annuals • Biennials • Perennials Annuals complete life cycles in one season Biennials live for 2 years, flower, then die Perennials live for 3 or more years, flower each year and usually do not die after flowering. Structures of Plants Roots Stems Leaves Flowers Seeds Examples of Stem Structure Herbaceous monocot and dicot stem Root cross-section • Apical meristem: point of vigorous cell division and growth. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations.