Probing the Economic Dimension of Temples in Goa: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY 2016 AFI Annual Report. (2017). Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publica- tions/2017-05/2016%20AFI%20Annual%20Report.pdf. A Law of the Abolition of Currencies in a Small Denomination and Rounding off a Fraction, July 15, 1953, Law No.60 (Shōgakutsūka no seiri oyobi shiharaikin no hasūkeisan ni kansuru hōritsu). Retrieved April 11, 2017, from https:// web.archive.org/web/20020628033108/http://www.shugiin.go.jp/itdb_ housei.nsf/html/houritsu/01619530715060.htm. About PBC. (2018, August 21). The People’s Bank of China. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/130712/index.html. About Us. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https:// www.afi-global.org/about-us. AFI Official Members. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/inlinefiles/AFI%20 Official%20Members_8%20February%202018.pdf. Ahamed, L. (2009). Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World. London: Penguin Books. Alderman, L., Kanter, J., Yardley, J., Ewing, J., Kitsantonis, N., Daley, S., Russell, K., Higgins, A., & Eavis, P. (2016, June 17). Explaining Greece’s Debt Crisis. The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2018, from https://www.nytimes. com/interactive/2016/business/international/greece-debt-crisis-euro.html. Alesina, A. (1988). Macroeconomics and Politics (S. Fischer, Ed.). NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 3, 13–62. Alesina, A. (1989). Politics and Business Cycles in Industrial Democracies. Economic Policy, 4(8), 57–98. © The Author(s) 2018 355 R. Ray Chaudhuri, Central Bank Independence, Regulations, and Monetary Policy, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58912-5 356 BIBLIOGRAPHY Alesina, A., & Grilli, V. -

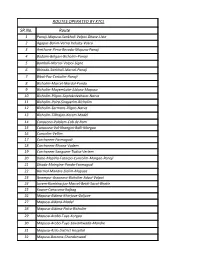

List of Representation /Objection Received Till 31St Aug 2020 W.R.T. Thomas & Araujo Committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No

List of Representation /Objection Received till 31st Aug 2020 w.r.t. Thomas & Araujo committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No. Sy.No. Penha de Leflor, H.no 223/7. BB Borkar Road Alto 1 Bardez Leo Remedios Mendes 9822121352 181/5 Franca Porvorim, Bardez Goa Penha de next to utkarsh housing society, Penha 2 Bardez Marianella Saldanha 9823422848 118/4 Franca de Franca, Bardez Goa Penha de 3 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa 7821965565 151/1 Franca Penha de 4 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa nill 151/93 Franca Penha de H.No. 583/10, Baman Wada, Penha De 5 Bardez Ujwala Bhimsen Khumbhar 7020063549 151/5 Franca France Brittona Mapusa Goa Penha de 6 Bardez Mumtaz Bi Maniyar Haliwada penha de franca 8007453503 114/7 Franca Penha de 7 Bardez Shobha M. Madiwalar Penha de France Bardez 9823632916 135/4-B Franca Penha de H.No. 377, Virlosa Wada Brittona Penha 8 Bardez Mohan Ramchandra Halarnkar 9822025376 40/3 Franca de Franca Bardez Goa Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 9 Bardez 9765830867 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. 236/20, Ward III, Haliwada, penha 8806789466/ 10 Bardez Mahboobsab Saudagar 134/1 Franca de franca Britona, Bardez Goa 9158034313 Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 11 Bardez 9765830867 135/3, & 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. -

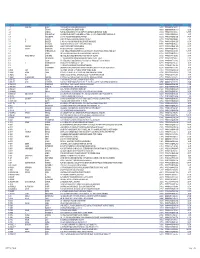

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the Study A) the Study Is Basically

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the study a) The study is basically a very good documentation of Goa's ancient and medieval period icons and sculptural remains. So far a wrong notion among many that Goa religio cultural past before the arrival of the Portuguese is intangible has been critically viewed and examined in this study. The research would help in throwing light on the pre-Portuguese era of the Goa's history. b) The craze of modernization and renovation of ancient and historic temples have made changes in the religio-cultural aspect of the society. Age old deities and concepts of worships have been replaced with new sculptures or icons. The new sculptures installed in places of the historic ones have been modified to the whims and fancies of many trustees or temple authorities thus changing the pattern of the religio-cultural past. While new icons substitute the old ones there are changes in attributes, styles and the historic features of the sculpture or image. Not just this but the old sculptures are immersed in water when the new one is being installed. Some customary rituals have been rapidly changed intentionally or unintentionally by the stake holders or the devotees. Moreover the most of the ancient rituals and customs associated with some icons have are in process of being stopped by the locals. Therefore a thorough documentation of these sculptures and antiquities with scientific attitude and research was the need of the hour. c) The iconographic details about many sculptures, worships or deities are scattered in many books and texts. -

List of Recognised Educational Institutions in Goa 2010

GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in C O N T E N T Sr. No. Page No. 1. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Non- Professional] … … … 1 2. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Professional] … … … … 5 3. Institutions for Professional/Technical Education in Goa [Post Matric Level] … … … 8 4. Institutions for Professional/Technical/Other Education in Goa [School Level]… … … 13 5. Higher Secondary Schools: Government and Government Aided & Unaided … … … 14 6. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … 22 7. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … 31 8. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 37 9. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 38 10. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 39 11. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 48 12. Government High Schools (Central and State) … … … … … … … … 56 13. Government Middle Schools [North & South Goa Districts] … … … … … … 60 14. Government Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … … … 63 15. Government Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … … … 87 16. Special Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … … 103 17. National Open Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … 104 AFFILIATED COLLEGES AND RECOGNISED INSTITUTIONS IN GOA [NON – PROFESSIONAL] Sr. -

Mission Rabies Goa Monthly Report – March 2018

Mission Rabies Goa Monthly Report – March 2018 Vaccination Total number of dogs vaccinated in March 2018 = 9,090 The temperatures in Goa have really started to rise but it has not deterred the Mission Rabies teams from vaccinating over 9,000 dogs in March 2018. Both the North and South squads have worked extremely hard and are progressing really well through the regions. The South squad (Figure 1) are expected to complete Ponda Taluka at the beginning of April 2018 and the map below (Figure 2) shows the vaccination coverage achieved in Ponda during March 2018. The North squad (Figure 3) are also hoping to complete Tiswadi Taluka towards the end of next month and the map in Figure 4 highlights the total vaccinations administered during March 2018. The areas marked in red are yet to be completed. Figure 1. Members of the Mission Rabies South squad hand-catching 1 Ponda Taluka Monthly Vaccination Coverage Figure 2. Ponda Taluka – Total vaccination coverage March 2018 Figure 3. One of the teams from the Mission Rabies North squad. Four dogs caught at the same time! 2 Tiswadi Taluka Monthly Vaccination Coverage Figure 4. Tiswadi Taluka – Total vaccination coverage March 2018 Rabies Surveillance, Testing and Research Total number of positive rabies cases in March 2018 = 3 The MR/WVS Rabies Response Team attended to ten suspected rabies cases during March 2018. Three were confirmed positive on post mortem and six were negative. One dog was placed in quarantine and as no signs of rabies developed the dog is due to be returned to its original location next week. -

The Tradition of Serpent Worship in Goa: a Critical Study Sandip A

THE TRADITION OF SERPENT WORSHIP IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY SANDIP A. MAJIK Research Student, Department of History, Goa University, Goa 403206 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: As in many other States of India, the State of Goa has a strong tradition of serpent cult from the ancient period. Influence of Naga people brought rich tradition of serpent worship in Goa. In the course of time, there was gradual change in iconography of serpent deities and pattern of their worship. There exist a few writings on serpent worship in Goa. However there is much scope to research further using recent evidences and field work. This is an attempt to analyse the tradition of serpent worship from a historical and analytical perspective. Keywords: Nagas, Tradition, Sculpture, Inscription The Ancient World The Sanskrit word naga is actually derived from the word naga, meaning mountain. Since all the Animal worship is very common in the religious history Dravidian tribes trace their origin from mountains, it of the ancient world. One of the earliest stages of the may probably be presumed that those who lived in such growth of religious ideas and cult was when human places came to be called Nagas.6 The worship of serpent beings conceived of the animal world as superior to deities in India appears to have come from the Austric them. This was due to obvious deficiency of human world.7 beings in the earliest stages of civilisation. Man not equipped with scientific knowledge was weaker than the During the historical migration of the forebears of animal world and attributed the spirit of the divine to it, the modern Dravidians to India, the separation of the giving rise to various forms of animal worship. -

SR.No. Route ROUTES OPERATED by KTCL

ROUTES OPERATED BY KTCL SR.No. Route 1 Panaji-Mapusa-Sankhali-Valpoi-Dhave-Uste 2 Agapur-Borim-Verna Industy-Vasco 3 Amthane-Pirna-Revoda-Mapusa-Panaji 4 Badami-Belgavi-Bicholim-Panaji 5 Bamboli-Marcel-Valpoi-Signe 6 Bhiroda-Sankhali-Marcel-Panaji 7 Bibal-Paz-Cortalim-Panaji 8 Bicholim-Marcel-Mardol-Ponda 9 Bicholim-MayemLake-Aldona-Mapusa 10 Bicholim-Pilgao-Saptakoteshwar-Narva 11 Bicholim-Poira-Sinquerim-Bicholim 12 Bicholim-Sarmans-Pilgao-Narva 13 Bicholim-Tikhajan-Kerem-Madel 14 Canacona-Palolem-Cab de Ram 15 Canacona-Val-Khangini-Balli-Margao 16 Cuncolim-Vellim 17 Curchorem-Farmagudi 18 Curchorem-Rivona-Vadem 19 Curchorem-Sanguem-Tudva-Verlem 20 Dabe-Mopirla-Fatorpa-Cuncolim-Margao-Panaji 21 Dhada-Maingine-Ponda-Farmagudi 22 Harmal-Mandre-Siolim-Mapusa 23 Ibrampur-Assonora-Bicholim-Advoi-Valpoi 24 Juvem-Kumbharjua-Marcel-Betki-Savoi-Bhatle 25 Kawar-Canacona-Rajbag 26 Mapusa-Aldona-Khorjuve-Goljuve 27 Mapusa-Aldona-Madel 28 Mapusa-Aldona-Poira-Bicholim 29 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Korgao 30 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Sawantwada-Mandre 31 Mapusa-Azilo District Hospital 32 Mapusa-Bastora-Chandanwadi 33 Mapusa-Bicholim-Poira 34 Mapusa-Bicholim-Sankhali-Valpoi-Hivre 35 Mapusa-Calvi-Madel 36 Mapusa-Carona-Amadi 37 Mapusa-Colvale-Dadachiwadi-Madkai 38 Mapusa-Duler-Camurli 39 Mapusa-Karurli-Aldona-Pomburpa-Panaji 40 Mapusa-Khorjuve-Bicholim-Varpal 41 Mapusa-Marna-Siolim 42 Mapusa-Nachnola-Carona-Calvi 43 Mapusa-Palye-Succuro-Bitona-Panaji 44 Mapusa-Panaji-Fatorpha(Sunday) 45 Mapusa-Pedne-Pednekarwada-Mopa 46 Mapusa-Saligao-Calangute-Pilerne-Panaji 47 Mapusa-Siolim -

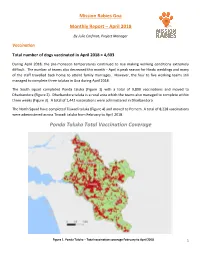

Ponda Taluka Total Vaccination Coverage

Mission Rabies Goa Monthly Report – April 2018 By Julie Corfmat, Project Manager Vaccination Total number of dogs vaccinated in April 2018 = 4,603 During April 2018, the pre-monsoon temperatures continued to rise making working conditions extremely difficult. The number of teams also decreased this month – April is peak season for Hindu weddings and many of the staff travelled back home to attend family marriages. However, the four to five working teams still managed to complete three talukas in Goa during April 2018. The South squad completed Ponda taluka (Figure 1) with a total of 9,800 vaccinations and moved to Dharbandora (Figure 2). Dharbandora taluka is a rural area which the teams also managed to complete within three weeks (Figure 3). A total of 1,442 vaccinations were administered in Dharbandora. The North Squad have completed Tiswadi taluka (Figure 4) and moved to Pernem. A total of 8,228 vaccinations were administered across Tiswadi taluka from February to April 2018. Ponda Taluka Total Vaccination Coverage Figure 1. Ponda Taluka – Total vaccination coverage February to April 2018 1 Figure 2. Moving time for the South squad Dharbandora Taluka Total Vaccination Coverage Figure 3. Dharbandora Taluka – Total vaccination coverage April 2018 2 Tiswadi Taluka Total Vaccination Coverage Figure 4. Tiswadi Taluka – Total vaccination coverage February to April 2018 This month was an exciting time for the Mission Rabies South Squad as they commenced hand-catching. Two teams consisting of an animal handler and a team leader took to the streets on mopeds; catching nets were replaced with slip leads, muzzles and dog food (Figures 5-10). -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Chinmay Madhu Ghaisas Assistant Professor, Dept. of Marathi, Goa University Office : Dept. of Marathi, Faculty Block B, Language & Literature Block, Goa University, Taleigao-Goa. 403206 Contact : 7030699149 E-mail : [email protected] Res.: H. No. 73, Orgao, Marcel-Goa. 403107 Contact : 9823728640 E-mail : [email protected] Academic Credentials :- Bachelor of Arts in Marathi & History from Goa University Bachelor of Education from Goa University Master of Arts in Marathi from Dept. of Marathi, University of Pune Post Graduate Diploma in Journalism & Mass Communication from Indira Gandhi National Open University UGC-NTA-NET Pursuing Ph.D. in Marathi from The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara-Gujarat on the topic ‘Marathi Sangeet Natak Ani Konkani Tiyatr Yancha Tyulanatmak Abhyas’ Work Experience :- Assistant Professor at Dept. of Marathi, Goa University Former Grade-I Teacher in Marathi at S. S. Samiti’s S.A.M.D. Higher Secondary School of Science, Kavale- Goa Former Casual News Reader-cum-Translator at Regional News Unit, All India Radio, Panaji-Goa Former Casual News Editor & Founding News Presenter at Regional News Unit, Doordarshan Kendra, Panaji-Goa Former News Anchor at Goa Plus News Channel, Panaji-Goa Other Highlights :- Subject expert for recruitment of Marathi teachers in the high schools, higher secondary schools & colleges Lead interviewer of All India Radio, Panaji & Doordarshan Kendra, Panaji for various political, social, cultural, academic programmes. Interviewed various -

S Goesas Em Konkani Songs From

GOENCHIM KONKNI GAIONAM 1 CANÇO?S GOESAS EM KONKANI2 SONGS FROM GOA IN KONKANI 1 Konkani 2 Portuguese 1 Goans spoke Portuguese but sang in Konkani, a language brought to Goa by the Indian Arya. + A Goan way of expressing love: “Xiuntim mogrim ghe rê tuka, Sukh ani sontos dhi rê maka.” These Chrysanthemum and Jasmine flowers I give to thee, Joy and happiness give thou to me. 2 Bibliography3 A selection as background information Refer to Pereira, José / Martins, Micael. “Goa and its Music”, in: UUUUBoletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Nr.155 (1988) pp. 41-72 (Bibliography 43-55) for an extensive selection and to the Mando Festival Programmes published by the Konkani Bhasha Mandal in Panaji for recent compositions. Almeida, Mathew . 1988. Konkani Orthography. Panaji: Dalgado Konknni Akademi. Barreto, Lourdinho. 1984. Goemchem Git. Pustok 1 and 2. Panaji: Pedro Barreto, Printer. Barros de, Joseph. 1989. “The first Book to be printed in India”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 159. pp. 5-16. Barros de, Joseph. 1993. “The Clergy and the Revolt in Portuguese Goa”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 169. pp. 21-37. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). 2000. Goa and Portugal. History and Development. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). Goa´s formost Nationalist: José Inácio Candido de Loyola. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. (Loyola is mentioned in the mando Setembrachê Ekvissavêru). Bragança, Alfred. 1964. “Song and Music”, in: The Discovery of Goa. Panaji: Casa J.D. Fernandes. pp. 41-53. Coelho, Victor A. -

SSC Result Booklet April-May 2020

Goa Board of Secondary & Higher Secondary Education Alto Betim-Goa APRIL-MAY 2020 Result Tuesday, 28th July, 2020 Certified that the Result of SSC Exam. April-May 2020 is prepared as per the rules of the Board in force. (Bhagirath G. Shetye) Secretary To be published strictly after 04.30 p.m. on 28th July, 2020 76 1 INDEX Sr.No. Particulars Page No. I Performance Report 3 II List of the Schools with Cent 4 Percent Results III School-wise Performance of 10 Candidates (at Glance) IV Centre-wise Performance of 33 candidates V Centre-wise Result 37 2 I. PERFORMANCE REPORT The SSC Examination was re-scheduled from 21st May, 2020 to 6th June, 2020 at 29 examination centres across the state, due to pandemic situation. A total of 18939 candidates registered under whole category (without exemption) for the SSC Examination of April-May, 2020. Out of 18939 candidates 17554 candidates pass the SSC Examination of April-May 2020 giving pass percentage of 92.69%. A total of 737 candidates registered under repeater/ITI category for the SSC Examination of April-May, 2020. Out of 737 candidates 345 candidates pass SSC Examination of April-May 2020 giving pass percentage of 46.81%. Result at a glance (Regular candidates): Appeared Passed Pass % Boys 9319 8581 92.08 Girls 9620 8973 93.27 Total 18939 17554 92.69 Highest and Lowest Pass Percentage centres Name of the Centre Enrollment Pass % Mangueshi 258 98.06 (Highest) Kepem 441 86.85 (Lowest) Highest and Lowest Enrollment centres Name of the Centre Enrollment Pass % Navelim 1522 94.28 (Highest) Paingin 230 96.96 (Lowest) 3 List of Schools with Cent Percent Results School Name Appeard Passed NI percentage 01.02-ST.