Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Train at Roundhay Pk App A.Pdf

Parks & Countryside OS Mapref = SE3337 Scale Roundhay Land Train Route 0 80 160 240 m I E E E 4 2 S U th T a o V C P T t S F 3 E 1 K N A R T L Nursery H A A S P N T K 6 P E a 5 1 N th C E E A 2 2 1 h B 8 U 6 t 9 C Stonecroft a t 3 2 N o 8 S P 9 E 1 30 9 1 E 2 1 V 27 R a A Club 1 2 10 C Y 9 4 3 R 1 El Sub W Key U Sta E The Cottage I B V S 32 E K 34 R T 3 F 6 1 A Garage A 33 P 1 H 2 3 4 3 5 S T 2 5 37 R 2 U 0 O 2 PARK VILLAS 2 2 3 C 2 8 4 40 37 The E 2 4 7 t 4 9 7 o Coach L 2 48 L Posts House I 3 Path V 9 Upper Lake 41 D 43 h O Pat P O AR Pond Fountain FB 127.1m 2 K V W 128.9m 5 ILL Ram Wood to AS Tropical World 36 9 1 o t 4 Sunday Robinwood 1 th a 1 White House 3 P 3 School Court 1 h t Waterfall to t a o 2 P 1 2 4 2 2 1 P 1 1 o A t R ta 1 S K b y h V u The Lodge a c S 8 FB r D IL l h u 9 E d L Waterfall h O A h n FB t u C S P a O a P o d 1 to th R e 6 W 4 2 G s m 1 N ' r a w o El Sub Sta R r f 6 e Fernwood 7 d Fn e to r 12 E 4 e d R n F 2 n Court d V A e 0 5 New t t ie 4 i 2 1 5 S n w 3 Rose U Bowling Green 1 C BM 128.38m 5 2 o Garden P ll 1 u ark Landing Stage Waterfa 0 C 1 ot Car 10 1 rt tages FB 8 Park 7 1 6 1 9 Pavilion Ramwood 7 D Fn 1 a F ERN 1 WO Pond OD 8 MANSION LANE 1 6 2 a 1 4 1 1 127.4m b Posts 7 1 127.7m 5 1 3 28 1 LB BM 125.43m to El Sub Sta 120.4m 25 3 127.1m ION LANE 2 1 26 0 MANS to BM 125.07m 3 27 a 128.9m Mansion House 95 Pond 4 7 D The to A 24 Roundhay Fox O 123.1m Rose Cottage R (PH) 24 K 3 Shelter R Mansion 30 28 A Cottage Mansion House 12 P 1 6 D 0 4 to 95 L 6 O alk w W 115.8m to 3 Ne 34 1 LB Leeds Golf Course Post -

From Bramley to CERN: How People Like You Took Me Back 14 Billion Years

From Bramley to CERN: How people like you took me back 14 billion years Dear Alum I’ve not invented a time machine, if that’s what you’re thinking. But I am one of a handful of people lucky enough to have studied physics at CERN, home to the Large Hadron Collider. Here, beams of protons are sent hurtling around a very long and incredibly Sam Gregson, PhD, former pupil of Leeds Grammar expensive pipe, then smashed into one another to recreate the conditions School that existed just after the big bang (around 13.7 billion years ago). Mind-blowing, isn’t it? At least, I think it is. I’ve always been fascinated by how things work, so the opportunity to work on my Cambridge University PhD at CERN, with some of the best particle physicists in the world, was a dream come true for me. But if it wasn’t for the bursary I received from Leeds Grammar School things would most likely have been very different for me. And that’s why I jumped at the chance to write this letter today and ask for your help. Will you give £50 to help fund bursaries at The Grammar School at Leeds and help pupils like me to reach their potential? Like you, I grew up in and around Leeds. I lived near Bramley with my mum, my brother and my late sister. We were a pretty normal working-class, single-parent family. I’d always assumed that after primary school I would go to the local comprehensive, so it came as a bit of a shock when my mum came in to my bedroom one day and said, “You have an exam tomorrow.” The Grammar School at Leeds There aren’t many 11-year-olds who like the idea of exams, but when she Alwoodley Gates explained what it meant in terms of opportunities, I was pretty happy to go Harrogate Road Leeds LS17 8GS along with it. -

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol. LV December 2019 The Pelican Record The President’s Report 4 Features 10 Ruskin’s Vision by David Russell 10 A Brief History of Women’s Arrival at Corpus by Harriet Patrick 18 Hugh Oldham: “Principal Benefactor of This College” by Thomas Charles-Edwards 26 The Building Accounts of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 1517–18 by Barry Collett 34 The Crew That Made Corpus Head of the River by Sarah Salter 40 Richard Fox, Bishop of Durham by Michael Stansfield 47 Book Reviews 52 The Renaissance Reform of the Book and Britain: The English Quattrocento by David Rundle; reviewed by Rod Thomson 52 Anglican Women Novelists: From Charlotte Brontë to P.D. James, edited by Judith Maltby and Alison Shell; reviewed by Emily Rutherford 53 In Search of Isaiah Berlin: A Literary Adventure by Henry Hardy; reviewed by Johnny Lyons 55 News of Corpuscles 59 News of Old Members 59 An Older Torpid by Andrew Fowler 61 Rediscovering Horace by Arthur Sanderson 62 Under Milk Wood in Valletta: A Touch of Corpus in Malta by Richard Carwardine 63 Deaths 66 Obituaries: Al Alvarez, Michael Harlock, Nicholas Horsfall, George Richardson, Gregory Wilsdon, Hal Wilson 67-77 The Record 78 The Chaplain’s Report 78 The Library 80 Acquisitions and Gifts to the Library 84 The College Archives 90 The Junior Common Room 92 The Middle Common Room 94 Expanding Horizons Scholarships 96 Sharpston Travel Grant Report by Francesca Parkes 100 The Chapel Choir 104 Clubs and Societies 110 The Fellows 122 Scholarships and Prizes 2018–2019 134 Graduate -

WEST LEEDS GATEWAY AREA ACTION PLAN Leeds Local Development Framework

WEST LEEDS GATEWAY AREA ACTION PLAN Leeds Local Development Framework Development Plan Document Preferred Options Main Report January 2008 1 Contact Details Write to: WLGAAP Team Planning and Economic Policy City Development Department Leeds City Council 2 Rossington Street Leeds LS2 8HD Telephone: 0113 2478075 or 2478122 Email: [email protected] Web: www.leeds.gov/ldf If you do not speak English and need help in understanding this document, please phone: 0113 247 8092 and state the name of your language. We will then contact an interpreter. This is a free service and we can assist with 100+ languages. We can also provide this document in audio or Braille on request. (Bengali):- 0113 247 8092 (Chinese):- 0113 247 8092 (Hindi):- 0113 247 8092 (Punjabi):- 2 0113 247 8092 (Urdu):- 0113 247 8092 3 Have Your Say Leeds City Council is consulting on the Preferred Options for the West Leeds Gateway between 26 th February 2008 and 8th April 2008. The Preferred Options and supporting documents are available for inspection at the following locations: • Development Enquiry Centre, City Development Department, Leonardo Building, 2 Rossington Street, Leeds, LS2 8HD (Monday-Friday 8.30am - 5pm, Wednesday 9.30am - 5pm) • Central Library, Calverley Street, LS1 3AB • Armley Library/One Stop Centre The documents are also published on the Council’s website. To download the proposals go to www.leeds.gov.uk/ldf and follow the speed link for the West Leeds Gateway Area Action Plan within the Local Development Framework. Paper copies of the document can be requested from the address below. A questionnaire is available to make comments. -

St Bede's Magazine

·~. ~ • ST BEDE'S MAGAZINE - BRADFORD Summer 1974 CONTEI\lTS RT. REV. MGR. C. TINDALL SCHOOL CAPTAIN'S REPORT SIXTH FORM EXECUTIVE ... I-lOUSE COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN'S REPORT ... EXAMINATION SUCCESSES ATHLETICS CALENDAR ATHLETICS RUGBY FOOTBALL CROSS COUNTRY CRICKET SWIMMING SOCIETIES: SENIOR SOCIETY 32 CHESS CLUB 33 THE SCOUT YEAR 36 MR. J. FATTORINI, K.S.G. MR. T. V. WALSH ... 37 IN BRIEF 39 SIXTH FORM MAGAZINE 40 MUSIC NOTES 41 FIELDWORK: BIOLOGY 42 UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES 43 OLD BOYS' NOTES 50 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 51 STAFF 1973-74 52 This Magazine is printed by W. Lobley & Sons Ltd., Wilsden, Bradford and set in 6pt., 8pt. and 'j Opt. Univers. 1 ST BEDE1S MAGAZINE SUMMER 1974 THE RIGHT REV. MGR. C. A. TINDAll, M.A. PROTONOTARY APOSTOLIC At the Requiem Mass for Mgr. Tindall celebrated at St. Robert's, Harrogate, on May 15th, 1974, the panegyric was delivered by Fr. F. Pepper. He has been kind enough to allow its reproduction, and for this we are greatly indebted to him. A MAN GOES OUT TO HIS WORK, AND TO HIS LABOUR UNTIL THE EVENING (Psalm 103) The morning of Charles Antony Tindall's life dawned in Bradford 93 years ago, born of a family, whose father's Yorkshire stock had remained true to the old Faith during the Reformation, and from whom he inherited that simple unquestioning loyalty to ALL the Church and Bishops taught, and, I think, a shrewdness and perceptiveness of his yeoman forebears; and from his Italian mother, a zest for life, an irrepressible gaiety, and a remarkable talent .for friendship. -

School and College (Key Stage 5)

School and College (Key Stage 5) Performance Tables 2010 oth an West Yorshre FE12 Introduction These tables provide information on the outh and West Yorkshire achievement and attainment of students of sixth-form age in local secondary schools and FE1 further education sector colleges. They also show how these results compare with other Local Authorities covered: schools and colleges in the area and in England Barnsley as a whole. radford The tables list, in alphabetical order and sub- divided by the local authority (LA), the further Calderdale education sector colleges, state funded Doncaster secondary schools and independent schools in the regional area with students of sixth-form irklees age. Special schools that have chosen to be Leeds included are also listed, and a inal section lists any sixth-form centres or consortia that operate otherham in the area. Sheield The Performance Tables website www. Wakeield education.gov.uk/performancetables enables you to sort schools and colleges in ran order under each performance indicator to search for types of schools and download underlying data. Each entry gives information about the attainment of students at the end of study in general and applied A and AS level examinations and equivalent level 3 qualiication (otherwise referred to as the end of ‘Key Stage 5’). The information in these tables only provides part of the picture of the work done in schools and colleges. For example, colleges often provide for a wider range of student needs and include adults as well as young people Local authorities, through their Connexions among their students. The tables should be services, Connexions Direct and Directgov considered alongside other important sources Young People websites will also be an important of information such as Ofsted reports and school source of information and advice for young and college prospectuses. -

The Leeds Scheme for Financing Schools

The Leeds Scheme for Financing Schools Made under Section 48 of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998 School Funding & Initiatives Team Prepared by Education Leeds on behalf of Leeds City Council Leeds Scheme April 2007 LIST OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The funding framework 1.2 The role of the scheme 1.2.1 Application of the scheme to the City Council and maintained schools 1.3 Publication of the scheme 1.4 Revision of the scheme 1.5 Delegation of powers to the head teacher 1.6 Maintenance of schools 2. FINANCIAL CONTROLS 2.1.1 Application of financial controls to schools 2.1.2 Provision of financial information and reports 2.1.3 Payment of salaries; payment of bills 2.1.4 Control of assets 2.1.5 Accounting policies (including year-end procedures) 2.1.6 Writing off of debts 2.2 Basis of accounting 2.3 Submission of budget plans 2.3.1 Submission of Financial Forecasts 2.4 Best value 2.5 Virement 2.6 Audit: General 2.7 Separate external audits 2.8 Audit of voluntary and private funds 2.9 Register of business interests 2.10 Purchasing, tendering and contracting requirements 2.11 Application of contracts to schools 2.12 Central funds and earmarking 2.13 Spending for the purposes of the school 2.14 Capital spending from budget shares 2.15 Financial Management Standard 2.16 Notice of concern 3. INSTALMENTS OF BUDGET SHARE; BANKING ARRANGEMENTS 3.1 Frequency of instalments 3.2 Proportion of budget share payable at each instalment 3.3 Interest clawback 3.3.1 Interest on late budget share payments 3.4 Budget shares for closing schools 3.5 Bank and building society accounts 3.5.1 Restrictions on accounts 3.6 Borrowing by schools 3.7 Other provisions 4. -

Leeds Secondary Admission Policy for September 2021 to July 2022

Leeds Secondary Admission Policy for September 2021 to July 2022 Latest consultation on this policy: 13 December 2019 and 23 January 2020 Policy determined on: 12 February 2020 Policy determined by: Executive Board Admissions policy for Leeds community secondary schools for the academic year September 2021 – July 2022 The Chief Executive makes the offer of a school place at community schools for Year 7 on behalf of Leeds City Council as the admissions authority for those schools. Headteachers or school-based staff are not authorised to offer a child a place for these year groups for September entry. The authority to convey the offer of a place has been delegated to schools for places in other year groups and for entry to Year 7 outside the normal admissions round. This Leeds City Council (Secondary) Admission Policy applies to the schools listed below. The published admission number for each school is also provided for September 2021 entry: School name PAN Allerton Grange School 240 Allerton High School 220 Benton Park School 300 Lawnswood School 270 Roundhay All Through School (Yr7) 210 Children with an education, health and care plan will be admitted to the school named on their plan. Where there are fewer applicants than places available, all applicants will be offered a place. Where there are more applicants than places available, we will offer places to children in the following order of priority. Priority 1 a) Children in public care or fostered under an arrangement made by the local authority or children previously looked after by a Local Authority. (see note 1) b) Pupils without an EHC plan but who have Special Educational Needs that can only be met at a specific school, or with exceptional medical or mobility needs, that can only be met at a specific school. -

Executive Board 21St September 2005 Present

EXECUTIVE BOARD 21ST SEPTEMBER 2005 PRESENT: Councillor Harris in the Chair Councillors D Blackburn, A Carter, J L Carter, Harker, Harrand, Jennings, Smith, Procter and Wakefield Councillor Blake – Non voting advisory member 49 Exclusion of the Public RESOLVED – That the public be excluded from the meeting during consideration of the appendices to the reports referred to in minutes 62 and 86 on the grounds that it is likely, in view of the nature of the business to be transacted or the nature of the proceedings, that if members of the public were present there would be disclosure to them of exempt information or confidential information, defined in Access to Information Procedure Rule 10.4 as indicated in the minute. 50 Declarations of Interest Councillors Wakefield and Smith declared personal interests in the item relating to Independence Wellbeing and Choice (minute 78) as non-executive members of the South Leeds Primary Care Trust. Councillor Harker declared a personal interest in the item relating to the North West Specialist Inclusive Learning Centre (minute 70) as a governor at the Centre. Councillor Harrand declared a personal and prejudicial interest in the item relating to small industrial units (minute 57) being an unpaid director of a company managing a group of small industrial units. 51 Minutes RESOLVED- That the minutes of the meeting held on 6th July 2005 be approved subject to a correction to minute 24 to show that the personal and prejudicial interest declared by Councillor A Carter was as a Director of a company engaged in business with the parent company of ASDA. -

Memories Come Flooding Back for Ogs School’S Last Link with Headingley

The magazine for LGS, LGHS and GSAL alumni issue 08 autumn 2020 Memories come flooding back for OGs School’s last link with Headingley The ones to watch What we did Check out the careers of Seun, in lockdown Laura and Josh Heart warming stories in difficult times GSAL Leeds United named celebrates school of promotion the decade Alumni supporters share the excitement 1 24 News GSAL launches Women in Leadership 4 Memories come flooding back for OGs 25 A look back at Rose Court marking the end of school’s last link with Headingley Amraj pops the question 8 12 16 Amraj goes back to school What we did in No pool required Leeds United to pop the question Lockdown... for diver Yona celebrates Alicia welcomes babies Yona keeping his Olympic promotion into a changing world dream alive Alumni supporters share the excitement Welcome to Memento What a year! I am not sure that any were humbled to read about alumnus John Ford’s memory and generosity. 2020 vision I might have had could Dr David Mazza, who spent 16 weeks But at the end of 2020, this edition have prepared me for the last few as a lone GP on an Orkney island also comes at a point when we have extraordinary months. Throughout throughout lockdown, and midwife something wonderful to celebrate, the toughest school times that Alicia Walker, who talks about the too - and I don’t just mean Leeds I can recall, this community has changes to maternity care during 27 been a source of encouragement lockdown. -

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

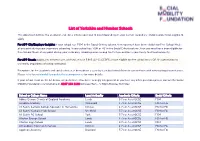

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

Open PDF 715KB

LBP0018 Written evidence submitted by The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium Education Select Committee Left behind white pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds Inquiry SUBMISSION FROM THE NORTHERN POWERHOUSE EDUCATION CONSORTIUM Introduction and summary of recommendations Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium are a group of organisations with focus on education and disadvantage campaigning in the North of England, including SHINE, Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) and Tutor Trust. This is a joint submission to the inquiry, acting together as ‘The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium’. We make the case that ethnicity is a major factor in the long term disadvantage gap, in particular white working class girls and boys. These issues are highly concentrated in left behind towns and the most deprived communities across the North of England. In the submission, we recommend strong actions for Government in particular: o New smart Opportunity Areas across the North of England. o An Emergency Pupil Premium distribution arrangement for 2020-21, including reform to better tackle long-term disadvantage. o A Catch-up Premium for the return to school. o Support to Northern Universities to provide additional temporary capacity for tutoring, including a key role for recent graduates and students to take part in accredited training. About the Organisations in our consortium SHINE (Support and Help IN Education) are a charity based in Leeds that help to raise the attainment of disadvantaged children across the Northern Powerhouse. Trustees include Lord Jim O’Neill, also a co-founder of SHINE, and Raksha Pattni. The Northern Powerhouse Partnership’s Education Committee works as part of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) focusing on the Education and Skills agenda in the North of England.