A Story of Placement a Habitat Solution for Communities in a Situation of Displacement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia

This is an extract from: Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia Jeffrey Quilter and John W. Hoopes, Editors published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2003 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html The Seed of Life: The Symbolic Power of Gold-Copper Alloys and Metallurgical Transformations Ana María Falchetti re-Hispanic metallurgy of the Americas is known for its technical variety. Over a period of more than three thousand years, different techniques were adopted by vari- Pous Indian communities and adapted to their own cultures and beliefs. In the Central Andes, gold and silver were the predominant metals, while copper was used as a base material. Central Andeans developed an assortment of copper-based alloys. Smiths hammered copper into sheets that would later be used to create objects covered with thin coatings of gold and silver. In northern South America and the Central American isth- mus gold-copper alloys were particularly common.1 Copper metallurgy was also important in Western Mexico and farther north. Putting various local technological preferences aside, Amerindians used copper exten- sively as a base material. What then were the underlying concepts that governed the symbol- ism of copper, its combination with other metals, and particular technologies such as casting methods in Pre-Columbian Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica? Studies of physical and chemical processes are essential to a scientific approach to met- allurgy, but for a fuller understanding, technologies should not be divorced from cultural contexts. -

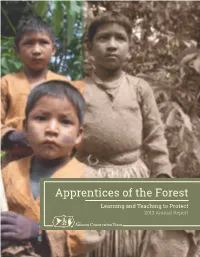

Apprentices of the Forest: 2013 Annual Report

Apprentices of the Forest Learning and Teaching to Protect 2013 Annual Report Letter from the President In all of its activities, ACT seeks partners who the old sciences have much to teach the new share this belief. When assessing partnerships sciences about adaptation—in effect, we with indigenous groups, ACT favors those should all be apprentices. communities with the greatest commitment to learning how to adapt and thrive under As the conservation story continues to evolve, rapidly changing ecological, social, and political ACT’s flexible, ambitious, and unwavering contexts. These kind of people possess the commitment to learning and traditional necessary drive to protect their traditional knowledge will ensure that we remain a territory and knowledge, as well as to transmit cutting-edge and resilient organization at the this capacity to future generations and forefront of the battle. neighboring groups. Since its inception, ACT has relied upon the bridging and blending of modern and ancient ways of knowing to forge the most effective solutions in biocultural conservation. In this effort, equally useful information and lessons can be obtained from scientific publications, Mark J. Plotkin, Ph.D., L.H.D. novel technologies, or fireside chats with tribal President and Cofounder In 2013, scientists made a remarkable discovery chieftains. In the example of the olinguito in the cloud forests of Ecuador and Colombia: discovery mentioned previously, the carnivore the first new carnivorous mammalian species would likely have been recognized as unique identified in the Americas in 35 years. years earlier if researchers had consulted more Amazingly, one specimen of this fluffy relative closely with local indigenous groups. -

The Cosmological, Ontological, Epistemological, and Ecological Framework of Kogi Environmental Politics

Living the Law of Origin: The Cosmological, Ontological, Epistemological, and Ecological Framework of Kogi Environmental Politics Falk Xué Parra Witte Downing College University of Cambridge August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Anthropology Copyright © Falk Xué Parra Witte 2018 Abstract Living the Law of Origin: The Cosmological, Ontological, Epistemological, and Ecological Framework of Kogi Environmental Politics This project engages with the Kogi, an Amerindian indigenous people from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range in northern Colombia. Kogi leaders have been engaging in a consistent ecological-political activism to protect the Sierra Nevada from environmentally harmful developments. More specifically, they have attempted to raise awareness and understanding among the wider public about why and how these activities are destructive according to their knowledge and relation to the world. The foreign nature of these underlying ontological understandings, statements, and practices, has created difficulties in conveying them to mainstream, scientific society. Furthermore, the pre-determined cosmological foundations of Kogi society, continuously asserted by them, present a problem to anthropology in terms of suitable analytical categories. My work aims to clarify and understand Kogi environmental activism in their own terms, aided by anthropological concepts and “Western” forms of expression. I elucidate and explain how Kogi ecology and public politics are embedded in an old, integrated, and complex way of being, knowing, and perceiving on the Sierra Nevada. I argue that theoretically this task involves taking a realist approach that recognises the Kogi’s cause as intended truth claims of practical environmental relevance. By avoiding constructivist and interpretivist approaches, as well as the recent “ontological pluralism” in anthropology, I seek to do justice to the Kogi’s own essentialist and universalist ontological principles, which also implies following their epistemological rationale. -

Anthropology

Anthropology Magic, Witchcraft, and Religion: A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion 8th Edition Moro−Myers McGraw-Hill=>? McGraw−Hill Primis ISBN−10: 0−39−021268−7 ISBN−13: 978−0−39−021268−9 Text: Magic, Witchcraft, and Religion: An Anthropological Study of the Supernatural, Eighth Edition Moro−Myers−Lehmann This book was printed on recycled paper. Anthropology http://www.primisonline.com Copyright ©2009 by The McGraw−Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. This McGraw−Hill Primis text may include materials submitted to McGraw−Hill for publication by the instructor of this course. The instructor is solely responsible for the editorial content of such materials. 111 ANTHGEN ISBN−10: 0−39−021268−7 ISBN−13: 978−0−39−021268−9 Anthropology Contents Moro−Myers−Lehmann • Magic, Witchcraft, and Religion: An Anthropological Study of the Supernatural, Eighth Edition Front Matter 1 Preface 1 1. The Anthropological Study of Religion 5 Text 5 2. Myth, Symbolism, and Taboo 46 Text 46 3. Ritual 87 Text 87 4. Shamans, Priests, and Prophets 143 Text 143 5. Altered States of Consciousness and the Religious Use of Drugs 188 Text 188 6. Ethnomedicine: Religion and Healing 240 Text 240 7. Witchcraft, Sorcery, Divination, and Magic 280 Text 280 8. Ghosts, Souls, and Ancestors: Power of the Dead 332 Text 332 9. -

The Three Faces of Justice: Legal Traditions, Legal Transplants, and Customary Justice in a Multicultural World

THE THREE FACES OF JUSTICE: LEGAL TRADITIONS, LEGAL TRANSPLANTS, AND CUSTOMARY JUSTICE IN A MULTICULTURAL WORLD by JUAN CARLOS BOTERO A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) at the Georgetown University Law Center 2013 i Copyright by Juan Carlos Botero 2013 ii Abstract This research explores the institutional and procedural architecture that enables or limits access to formal and informal dispute settlement mechanisms to resolve simple disputes among individuals in developing countries. The central argument is that the urban poor (including newly arrived migrant peasants and members of indigenous communities) in developing countries, are unable to keep their traditions and ancestral dispute settlement mechanisms alive in big cities, while they are also unable to understand and utilize what to them are abstruse legal procedures of the formal courts. A proposal is made at the end of the dissertation, which includes a novel conceptual framework to analyze the problem of deficient delivery of justice (formal and customary) to the urban poor, and a methodology to quantify the multiple dimensions of the same problem in low and middle-income countries throughout the world. The contribution of this work is: first, a new conceptual framework for the comparative analysis of formal and informal justice in developed and developing countries. Second, to expand knowledge on the uneasy interaction among legal traditions, legal transplants and customary justice in the multicultural world of the XXI century. Third, a descriptive analysis of a chronic problem which affects billions of people, i.e., the lack of effective access to justice (formal or customary) for the urban poor in low and middle-income countries. -

Colombia – Index

336 ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd San Agustín 235-7 Playa Olímpica 255 Tierradentro 239-41, 240 Playa Soledad 165 architecture 102-3, 175, 197 Playa Taroa 159 area codes 17, 311 Providencia 177 Armenia 211-13 Punta Gallinas 159 Arrecifes 151, 152 Punta Huína 252-3 art museums Riohacha 156 Bogotá 50 San Luis 171-2 Casa Museo Pedro Santa Catalina 177 Nel Gómez 187 Tolú 162 Museo Arquidiocesano de Arte Belalcázar, Sebastián de 220, 229, Religioso 111 280, 282 Museo de Antioquia 183 A Betancur, Belisario 284-5 Museo de Arte Colonial 47 bicycling 290, 317-18, see also abseiling 31, 100, 13 Museo de Arte del Banco de la mountain biking Acandí 166 República 47 Bogotá 51 accommodations 303-4, see also Museo de Arte Moderno Villa de Leyva 86 individual locations (Barranquilla) 138 birds 295 language 322-3 Museo de Arte Moderno (Bogotá) bird-watching 30 activities 28-32, see also individual 50 activities books 30, 295 Museo de Arte Moderno Los Llanos 76 aguardiente 320 (Cartagena) 121 Minca 145-6 air travel 314-15, 316-17, 317 Museo de Arte Moderno de altitude sickness 306 Bucaramanga 107 Parque Nacional Natural (PNN) Amacayacu 270 Alto de la Cueva 98-9 Museo de Arte Moderno de Parque Ucumarí 211 Alto de las Piedras 237 Medellín 187 Playa Mecana 253 Alto de Lavapatas 236 Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia 221 Recinto del Pensamiento 203 Amazon Basin 35, 262-74, 263, 9 Museo de Arte Moderno Ramírez Reserva Ecológica accommodations 262 Villamizar 111 Río Blanco 203 climate 262 arts 291-3, see also individual arts Río Claro 199 food 262 ATMs 17, 308 Río Yavarí 272 highlights 263 AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los travel seasons 262 Colombia) 284, 286 Flamencos 157 Andrés Carne de Res 62 Santuario Otún Quimbaya 210 animals 295, see also birds, bird- boat travel 318, see also canoeing, watching, dolphin-watching, B kayaking, white-water rafting Bahía Solano 251-2 endangered species, turtles, boat trips whale-watching, wildlife bargaining 277, 309 dangers 132 aquariums Barichara 10, 102-6, 103 Guatapé 196 Isla Palma 163-4 Barranquilla 136-9. -

The Poetics of Indigenous Radio in Colombia Clemencia Rodríguez1 UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA Jeanine El Gazi MINISTRY of CULTURE,COLOMBIA

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository The poetics of indigenous radio in Colombia Clemencia Rodríguez1 UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA Jeanine El Gazi MINISTRY OF CULTURE,COLOMBIA In 2002, 14 indigenous radio stations began operating in Colombia, reaching 78.6 percent of the national indigenous population (Ministerio de Cultura, 2002: 10). In this article we intend to shed light on the complex relationships and interactions behind Colombian indigenous radio stations. Colombian indigenous radio can only be understood as a product of intricate relation- ships between indigenous social movements, armed conflict, the state and media activism. In the following pages we will explain how Colombian indigenous peoples articulate a strong and highly developed response toward the presence of media technologies among their communities. This response is framed by new legislative frameworks made possible by the constitutional reform of 1991, by indigenous peoples’ critique of Colombian mainstream media and, finally, by discussions among indigenous peoples about the adop- tion of radio – what we call a poetics of radio. The data for this article comes mostly from unpublished documents, archives and recordings kept at the Ministry of Culture (Unidad de Radio/Office of Radio). The Colombian indigenous population is 708,000; despite the fact that they constitute less than 2 percent of the national population and include more than 80 different ethnic groups with their corresponding languages, widely scat- tered across a rough terrain, indigenous people have both captured and repre- sented some of the most significant notions in Colombia’s modern political arena.2 Colombian indigenous people have played a remarkable role in the political consciousness and imaginaries in contemporary Colombia. -

UMUNUKUNU.Pdf

UMUNUKUNU ÁLVARO SALAMANCA BALEN JUAN PABLO RICO GÓMEZ LUNA ANDRADE ARANGO DOCUMENTAL PROYECTO CREATIVO DE CARÁCTER AUDIOVISUAL EDWARD GOYENECHE GÓMEZ DIRECTOR DE TRABAJO DE GRADO UNIVERSIDAD DE LA SABANA FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MULTIMEDIOS CHÍA 2018 1 RESUMEN Umunukunu es un proyecto audiovisual documental que busca elaborar una reflexión en torno a los significados de riqueza y de pobreza como resultado de una investigación etnográfica de los indígenas Kogui de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Para la realización de este documental, se llevó a cabo una investigación bibliográfica y de campo sobre diversos aspectos históricos, geográficos y antropológicos de la Sierra y de las comunidades que la habitan. Como resultado de la investigación, se plantea una propuesta audiovisual que busca plasmar las vivencias de los Kogui de forma narrativa a través del viaje de Manuel, el protagonista del documental. PalAbrAs clAve: audiovisual, cine etnográfico, cultura kogui, documental, indígena, pobreza, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. ABSTRACT Umunukunu is an audiovisual documentary project that aims to elaborate a reflection regarding the meanings of richness and poverty, through ethnographic research of Kogui people in Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. To record this documentary, bibliographic and field research about historical, geographical and anthropological aspects on Sierra Nevada and the people who inhabits there was done. The audiovisual proposal focuses on showing Kogui’s life in a narrative way through Manuel’s journey, the main character of the documentary. Key words: audiovisual, documentary, ethnographic film, Kogui culture, native, poverty, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. 2 ÍNDICE 1. Introducción 5 2. -

Discovering Colombia 24 February – 8 March 2020

DISCOVERING COLOMBIA 24 FEBRUARY – 8 MARCH 2020 FROM £4,690 PER PERSON Tour Leaders: Robin & Louella Hanbury-Tenison PICTURESQUE CITIES AND LUSH LANDSCAPES Colombia still lies largely undiscovered, but with direct flights with Avianca from London to Bogotá, now is the time to visit. Our tour starts in the thriving modern and affluent city of Bogotá where we explore the historic centre known as La Candelaria with its old casonas or grand colonial Spanish houses with iron windows, thick wooden doors, balconies and internal patios that hide beautiful gardens. From here we travel, via the impressive salt cathedral at Zipaquirá, to the village of Villa de Leyva, one of the most beautiful colonial towns in the area which was founded in 1572 and declared a national monument in 1954. We continue to Pereira in the Coffee Region, where there is a day trip to the Valle de Cocora to see the amazing wax palm trees that can reach a height of 60m and the neighbouring towns of Salento and Filandia. We also see one of the plantations set on the steep hills which are typical of this area. We then travel to Santa Marta which is our base from which to dip into the Tayrona National Park, with its 37,000 acres of lush mountain landscape in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada and perfect sandy beaches. We also undertake a day’s excursion into the foothills to visit a community of the Kogi, descendants of the Tairona culture who flourished before the Spanish conquest. We will meet one of their priests, known as Mamo, who rarely interact with the modern world in order to preserve their traditional way of life. -

The Peccary with Observations on the Introduction of Pigs to the New World

TRANSACTIONS of the American Philosophical Society Held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge VOLUME 75, Part 5, 1985 The Peccary With Observations on the Introduction of Pigs to the New World R. A. DONKIN This content downloaded from 201.153.156.46 on Thu, 12 Jul 2018 05:28:14 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms TRANSACTIONS of the American Philosophical Society Held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge VOLUME 75, Part 5, 1985 The Peccary With Observations on the Introduction of Pigs to the New World R. A. DONKIN Fellow of Jesus College Cambridge THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Independence Square, Philadelphia 1985 This content downloaded from 201.153.156.46 on Thu, 12 Jul 2018 05:28:22 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Copyright ( 1985 by The American Philosophical Society Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 84-45906 International Standard Book Number 0-87169-755-6 US ISSN 0065-9746 This content downloaded from 201.153.156.46 on Thu, 12 Jul 2018 05:28:22 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms CONTENTS Page List of Maps .......................... v List of Figures .......................................... vi Preface ................................................ vii Part I: Distribution, Habitat, and Biology A. Description ............ ............................ 3 B. Scientific Nomenclature ....... ...................... 6 C. Distribution ............ ........................... 9 D. Habitat and Diet ................................... 18 E. Biology and Behavior ........ ....................... 23 Part II: The Peccary in Human Economy and Society A. The Pre-Columbian Period ....... .................... 29 B. European Contact ......... ......................... 35 C. Folk Nomenclature ........ ......................... 48 D. Hunting .............. ............................ 65 E. Taboo, Ceremony, and Myth ...... ................... 83 F. Towards Domestication ....... ....................... 95 G. -

Human Rights in Minefields

HUMAN RIGHTS IN MINEFIELDS EXTRACTIVE ECONOMIES, ENVIRONMENTAL CONFLICTS, AND SOCIAL JUSTICE IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH Human Rights in Minefields Extractive Economies, Environmental Conflicts, and Social Justice in the Global South César Rodríguez-Garavito Director Rodríguez-Garavito, César (dir.), Carlos Andrés Baquero Díaz, Asanda Benya, Michael Burawoy, Omaira Cárdenas Mendoza, Mariana González Armijo, Karl von Holdt, Arpitha Kodiveri, Maximiliano Mendieta Miranda, Meghan L. Morris, Ida Nakiganda, Cristián Sanhueza Cubillos, Marisa Viegas e Silva, Nandini Sundar, María José Veramendi Villa, Wilmien Wicomb. Human Rights in Minefields. Extractive Economies, Environmental Conflicts, and Social Justice in the Global South. Bogotá: Center for the Study of Law, Justice and Society, Dejusticia, 2015 386 p; 15 x 24 cm (Dejusticia Series) ISBN 978-958-59037-7-7 Digital Edition 978-958-59037-8-4 Printed Edition 1. Colombia. 2. India. 3. South Africa. 4. India. 5. Chile. 6. Mexico. 7. Uganda. 8. Paraguay. 9. Peru. 10. Brazil. 11. Extractive Industries. 12. Natural Resources. 13. Indigenous Peoples. 14. Action Research . The publication of this book was supported by the Ford Foundation. ISBN 978-958-59037-7-7 Digital Edition 978-958-59037-8-4 Printed Edition Translation & Copy Editing Morgan Stoffregen Layout Marta Rojas Cover Alejandro Ospina Printed by Ediciones Antropos First English Edition Bogotá, Colombia, July 2015 This document is available at http://www.dejusticia.org Creative Commons Licence 2.5 Attibution Non-Commercial Share-Alike Dejusticia, -

Updated Pack Clean

Press Pack 1 www.alunathemovie.com Press Pack Contents Short Synopsis Full Synopsis Credits and contact details Kogi Facts and figures Director Biography Language notes Main characters Eradicating Ecocide Short Synopsis In 1990, a BBC1 documentary film brought global attention to a remote South American people, the Kogi of ColomBia, who were determined to caution us aBout environmental damage to the earth. Now, two decades later and convinced that their message has gone unheeded, the next generation of Kogi are reaching out to the world once more with a much more specific warning about the future of the planet. Full Synopsis Twenty years ago Alan Ereira’s influential television film From The Heart of the World: The Elder Brothers’ Warning, brought gloBal attention to the Kogi people of ColomBia - a remote and ancient South American civilization - who were determined to caution us aBout environmental damage to the earth. A true ‘lost civilization’, who regard themselves as the guardians of the earth, the Kogi once traded with the Mayans and Aztecs. They survived the Spanish conquests By retreating into their isolated mountain massif, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Having remained hidden for centuries, the Kogi surfaced in Ereira’s 1990 film with an environmental message that was ahead of its time, a warning about how we, their ‘younger brother’, were destroying the ecosystem by plunder. But the Kogi have continued to see frightening changes to their homeland as highways and power plants spring up and glacial melt, ferocious storms, landslides, floods, droughts and deforestation continue to take their toll. 2 www.alunathemovie.com The Kogi maintain that their warning was rooted in their own scientific knowledge.