Missionaries' Impact on the Formation of Modern Art In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa Digests the West: a Review of Modernism and the Influence of Patrons-Cum Brokers on the Style and Form of Southern Eastern and Central African Art

ISSN-L: 2223-9553, ISSN: 2223-9944 Part-I: Social Sciences and Humanities Vol. 4 No. 1 January 2013 AFRICA DIGESTS THE WEST: A REVIEW OF MODERNISM AND THE INFLUENCE OF PATRONS-CUM BROKERS ON THE STYLE AND FORM OF SOUTHERN EASTERN AND CENTRAL AFRICAN ART Phibion Kangai 1, Joseph George Mupondi 2 1Department of Teacher Education, University of Zimbabwe, 2Curriculum Studies Department, Great Zimbabwe University, ZIMBABWE. 1 [email protected] , 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Modern Africa Art did not appear from nowhere towards the end of the colonial era. It was a response to bombardment by foreign cultural forms. African art built itself through “bricolage” Modernism was designed to justify colonialism through the idea of progress, forcing the colonized to reject their past way of life. Vogel (1994) argues that because of Darwin’s theory of evolution and avant-garde ideology which rejected academic formulas of representation, colonialists forced restructuring of existing artistic practice in Africa. They introduced informal trainings and workshops. The workshop patrons-cum brokers did not teach the conventions of art. Philosophically the workshops’ purpose was to release the creative energies within Africans. This assumption was based on the Roseauian ideas integrated culture which is destroyed by the civilization process. Some workshop proponents discussed are Roman Desfosses, of colonial Belgian Congo, Skotness of Polly Street Johannesburg, McEwen National Art Gallery Salisbury and Bloemfield of Tengenenge. The entire workshop contributed to development of black art and the birth of genres like Township art, Zimbabwe stone sculpture and urban art etc. African art has the willingness to adopt new ideas and form; it has also long appreciation of innovation. -

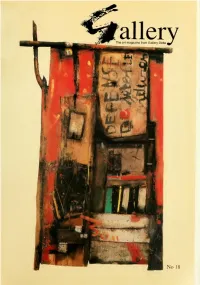

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine; ff^VoS SISIB Anglo American Corporation Services Limited T1HTO The Rio Tinto Foundation APEXAPEZCOBTCOBPOBATION OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht ^RISTON ^.Tanganda Tea Company Limited A-"^" * ETWORK •yvcoDBultaots NDORO Contents March 1997 Artnotes : the AICA conference on Art Criticism & Africa Burning fires or slumbering embers? : ceramics in Zimbabwe by Jack Bennett The perceptive eye and disciplined hand : Richard Witikani by Barbara Murray 11 Confronting complexity and contradiction : the 1996 Heritage Exhibition by Anthony Chennells 16 Painting the essence : the harmony and equilibrium of Thakor Patel by Barbara Murray 20 Reviews of recent work and forthcoming exhibitions and events including: Earth. Water, Fire: recent work by Berry Bickle, by Helen Lieros 10th Annual VAAB Exhibition, by Busani Bafana Explorations - Transformations, by Stanley Kurombo Robert Paul a book review by Anthony Chennells Cover: Tendai Gumbo, vessel, 1995, 25 x 20cm, terracotta, coiled and pit-fired (photo credit: Jack Bennett & Barbara Murray) Left: Crispen Matekenya, Baboon Chair, 1996, 160 x 1 10 x 80cm, wood © Gallery Publications Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Design & typesetting: Myrtle Mollis. Originaiion: HPP Studios. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Paper: Magno from Graphtec Lid. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta, the publisher or the editor Articles are invited for submission. -

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: APEX CDRPORATIDN OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht NDORO ^RISTON Contents December 1998 2 Artnotes 3 New forms for old : Dak" Art 1998 by Derek Huggins 10 Charting interior and exterior landscapes : Hilary Kashiri's recent paintings by Gillian Wright 16 'A Changed World" : the British Council's sculpture exhibition by Margaret Garlake 21 Anthills, moths, drawing by Toni Crabb 24 Fasoni Sibanda : a tribute 25 Forthcoming events and exhibitions Front Cover: TiehenaDagnogo, Mossi Km, 1997, 170 x 104cm, mixed media Back Cover: Tiebena Dagnogo. Porte Celeste, 1997, 156 x 85cm, mixed media Left: Tapfuma Gutsa. /// Winds. 1996-7, 160 x 50 x 62cm, serpentine, bone & horn © Gallery Publications ISSN 1361 - 1574 Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Designer: Myrtle Mallis. Origination: Crystal Graphics. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta. Gallery Publications, the publisher or the editor Articles and Letters are invited for submission. Please address them to The Editor Subscriptions from Gallery Publications, c/o Gallery Delta. 110 Livingstone Avenue, P.O. Box UA 373. Union Avenue, Harare. Zimbabwe. Tel & Fa.x: (263-4) 792135, e-mail: <[email protected]> Artnotes A surprising fact: Zimbabwean artworks are Hivos give support to many areas of And now, thanks to Hivos. -

Mashonaland Central Province : 2013 Harmonised Elections:Presidential Election Results

MASHONALAND CENTRAL PROVINCE : 2013 HARMONISED ELECTIONS:PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION RESULTS Mugabe Robert Mukwazhe Ncube Dabengwa Gabriel (ZANU Munodei Kisinoti Welshman Tsvangirayi Total Votes Ballot Papers Total Valid Votes District Local Authority Constituency Ward No. Polling Station Facility Dumiso (ZAPU) PF) (ZDP) (MDC) Morgan (MDC-T) Rejected Unaccounted for Total Votes Cast Cast Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 1 Bindura Primary Primary School 2 519 0 1 385 6 0 913 907 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 1 Bindura Hospital Tent 0 525 0 8 521 11 0 1065 1054 2 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 2 1,044 0 9 906 17 0 1,978 1,961 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 2 Bindura University New Site 0 183 2 1 86 2 0 274 272 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 2 Shashi Primary Primary School 0 84 0 2 60 2 0 148 146 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 2 Zimbabwe Open UniversityTent 2 286 1 4 166 5 0 464 459 3 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 2 553 3 7 312 9 0 886 877 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 3 Chipindura High Secondary School 2 80 0 0 81 1 2 164 163 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 3 DA’s Campus Tent 1 192 0 7 242 2 0 444 442 2 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 3 272 0 7 323 3 2 608 605 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 4 Salvation Army Primary School 1 447 0 7 387 12 0 854 842 1 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 1 447 0 7 387 12 0 854 842 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 5 Chipadze A Primary School ‘A’ 0 186 2 0 160 4 0 352 348 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 5 Chipadze B -

Structure and Meaning in the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe

STRUCTURE AND MEANING IN THE PREHISTORIC ART OF ZIMBABWE PETER S. GARLAKE Seventeenth Annual Mans Wolff Memorial Lecture April 15, 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana Copyright 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University All rights reserved ISBN 0-941934-51-9 PETER S. GARLAKE Peter S. Garlake is an archaeologist and the author of many books on Africa. He has conducted fieldwork in Somalia, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Qatar, the Comoro Islands and Mozambique, and has directed excavations at numerous sites in Zimbabwe. He was the Senior Inspector of Monuments in Rhodesia from 1964 to 1970, and a senior research fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ife from 1971 to 1973. From 1975 to 1981, he was a lecturer in African archaeology and material culture at the Department of Anthropology, University College, University of London. F.rom 1981 to 1985, he was attached to the Ministry of Education and Culture in Zimbabwe and in 1984-1985 was a lecturer in archaeology at the University of Zimbabwe. For the past year, he has been conducting full time research on the prehistoric rock art of Zimbabwe. He is the author of Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast, 1966; Great Zimbabwe, 1973; The Kingdoms of Africa, 1978; Great Zimbabwe Described and Exglained, 1982; Life qt Great Zimbabwe, 1982; People Making History, 1985; and is currently writing The Painted Caves. Peter Garlake is a contributor to the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archaeology, the hpggqn ---Encyclopedia --- ---- of Africa and the MacMillan Dictionary of big, and is the author of many journal and newspaper articles. -

Download (4MB)

Evelyn Waugh in his library at Piers Court In 1950. This photograph by Douglas Glass appeared in "Portrait Gallery" ln the Sunday T;m~s, January 7, 1951. Waugh had recently published Hel~nQ (1950), and he was about to start writing M~n at Arms (1952), the first volume of the trilogy that became Sword o/Honour (1965). C J. C. C. Glass "A Handful of Mischief" New Essays on Evelyn Waugh Edited by Donat Gallagher, Ann Pasternak Slater, and John Howard Wilson Madison· Teaneck Fairleigh Dickinson University Press Published by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press Co-publisbed with The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rlpgbooks.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright C 2011 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or me<:hanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data on file under LC#2010016424 ISBN: 978-1-61147-048-2 (d. : alk. paper) eISBN: 978-1-61147-049-9 e"" The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences- Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSIINISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America To Alexander Waugh, who keeps the show on the road Contents Acknowledgments 9 Abbreviations 11 Introduction ROBERT MURRAY DAVIS 13 Evelyn Waugh, Bookman RICHARD W. -

Chapungu Sculpture Park

CHAPUNGU SCULPTURE PARK Do you Chapungu (CHA-poon-goo)? The real showcase within the Centerra community is the one-of-a-kind Chapungu Sculpture Park. Nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, this 26-acre outdoor cultural experience features more than 80 authentic stone sculptures carved by artisans from Zimbabwe displayed amongst beautiful natural and landscaped gardens. The entire walking park which is handicap accessible, orients visitors to eight universal themes, which include: Nature & Environment • Village Life • The Role of Women • The Elders • The Spirit World • The Family The Children • Custom & Legend. Whether you are an art enthusiast or just enjoy the outdoors, this serenity spot is worth checking out. Concrete and crushed rock used from the makings of the sculptures refine trails and lead you along the Greeley and Loveland Irrigation Canal and over bridges. Soak in the sounds of the birds perched high above in the cottonwood trees while resting on a park bench with a novel or newspaper in hand. Participate in Centerra’s annual summer concert series, enjoy a self guided tour, picnic in the park, or attend Visit Loveland’s Winter Wonderlights hosted F R E E A D M I S S I O N at the park and you are bound to have a great experience each time you visit. Tap Into Chapungu Park Hours: Daily from 6 A.M. to 10:30 P.M. Easily navigate all the different Chapungu Sculpture Park is conveniently located just east of the Promenade Shops at Centerra off Hwy. 34 and regions within Chapungu Located east of the Promenade Shops Centerra Parkway in Loveland, Colorado. -

Culture and Customs of Zimbabwe 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page Ii

6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page i Culture and Customs of Zimbabwe 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page ii Recent Titles in Culture and Customs of Africa Culture and Customs of Nigeria Toyin Falola Culture and Customs of Somalia Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi Culture and Customs of the Congo Tshilemalema Mukenge Culture and Customs of Ghana Steven J. Salm and Toyin Falola Culture and Customs of Egypt Molefi Kete Asante 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page iii Culture and Customs of Zimbabwe Oyekan Owomoyela Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page iv Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Owomoyela, Oyekan. Culture and customs of Zimbabwe / Oyekan Owomoyela. p. cm.—(Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–31583–3 (alk. paper) 1. Zimbabwe—Social life and customs. 2. Zimbabwe—Civilization. I. Title. II. Series. DT2908.O86 2002 968.91—dc21 2001055647 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2002 by Oyekan Owomoyela All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2001055647 ISBN: 0–313–31583–3 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). -

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 Through October 31, 2007 ABOUT the ARTISTS

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 through October 31, 2007 ABOUT THE ARTISTS Dominic Benhura, b. 1968 in Murewa – “Who Is Strongest?”, “Zimbabwe Bird” At age 10 Benhura began to assist his cousin, sculptor Tapfuma Gutsa, spending many formative years at Chapungu Sculpture Park. Soon after he began to create his own works. Today he is regarded as the cutting edge of Zimbabwe sculpture. His extensive subject matter includes plants, trees, reptiles, animals and the gamut of human experience. Benhura has an exceptional ability to portray human feeling through form rather than facial expression. He leads by experimentation and innovation. Ephraim Chaurika, b. 1940 in Zimbabwe – “Horse” Before joining the Tengenenge Sculpture Community in 1966, Chaurika was a herdsman and a local watchmaker. He engraved the shape of watch springs and cog wheels in some of his early sculptures. His early works were often large and powerfully expressive, sometimes using geometric forms, while later works are more whimsical and stylistic. His sculptures are always skillful, superbly finished and immediately appealing. Sanwell Chirume, b. 1940 in Guruve – “Big Buck Surrendering” Chirume is a prominent Tengenenge artist and a relative of artist Bernard Matemura. He first visited Tengenenge in 1971 to help quarry stone. In 1976 he returned to become a full time sculptor. Largely unacknowledged, he nevertheless creates powerful large sculptures of considerable depth. His work has been in many major exhibitions, has won numerous awards in the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, and is featured in the Chapungu Sculpture Park’s permanent collection. Edward Chiwawa, b. 1935 northwest of Guruve – “Lake Bird” This first generation master sculptor learned to sculpt by working with his cousin, Henry Munyaradzi. -

Catalogue 97

Eastern Africa A catalogue of books concerning the countries of Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and Malawi. Catalogue 97 London: Michael Graves-Johnston, 2007 Michael Graves-Johnston 54, Stockwell Park Road, LONDON SW9 0DA Tel: 020 - 7274 – 2069 Fax: 020 - 7738 – 3747 Website: www.Graves-Johnston.com Email: [email protected] Eastern Africa: Catalogue 97. Published by Michael Graves-Johnston, London: 2007. VAT Reg.No. GB 238 2333 72 ISBN 978-0-9554227-1-3 Price: £ 5.00 All goods remain the property of the seller until paid for in full. All prices are net and forwarding is extra. All books are in very good condition, in the publishers’ original cloth binding, and are First Editions, unless specifically stated otherwise. Any book may be returned if unsatisfactory, provided we are advised in advance. Your attention is drawn to your rights as a consumer under the Consumer Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations 2000. The illustrations in the text are taken from item 49: Cott: Uganda in Black and White. The cover photograph is taken from item 299: Photographs. East Africa. Eastern Africa 1. A Guide to Zanzibar: A detailed account of Zanzibar Town and Island, including general information about the Protectorate, and a description of Itineraries for the use of visitors. Zanzibar: Printed by the Government Printer, 1952 Wrpps, Cr.8vo. xiv,146pp. + 18pp. advertisements, 4 maps, biblio., appendices, index. Slight wear to spine, a very nice copy in the publisher’s pink wrappers. £ 15.00 2. A Plan for the Mechanized Production of Groundnuts in East and Central Africa. Presented by the Minister of Food to Parliament by Command of His Majesty February, 1947. -

The Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: The Rio Tinto Foundation Colorscan (Pvt) Ltd. ^ jmz coBromATiOM or zimbabwx ldoted MEIKLES HOTEL CODE THE CANADIAN ORGANIZATION FOR DEVELOI'MKNI IHROUCH KDUCATION Contents June 1995 2 Artnotes Art about Zimbabwe by Pip Curlin 6 I have a gallery in Africa: the origins of Gallery Delta by Derek Huggins 10 A gift that was hiding: Job Kekana by Pip Curling 12 Living and working in the mission tradition: in memoham Job Kekana by Elizabeth Rankin » \ 13 Helen Lieros: an interview with Barbara Murray 19 Letters 20 Reviews of recent work and forthcoming exhibitions and events Cover: Helen Lieros, Cataclysm, 1994, 1 12 x 86cm, mixed media. Photo by Dani Deudney Left: Zephania Tshuma, No Way To Go, 1986, 75 x 10 x 10cm, painted wood © Gallery Publications Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Design & typesetting: Myrtle Mallis. Origination & printing by AW. Bardwell & Co. Colour by Colourscan (Pvt) Ltd. Paper; Express from Graphtec Ltd, Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta, the publisher or the editor. Subscriptions from Gallery Publications, 7^ Gallery Delta, 1 10 Livingstone Avenue, PO Box UA 373 Union Avenue, Harare. Tel: (14)792135. -i Artnotes In his last interview, Job Kekana said, "When you travel between people it makes your knowledge stronger," and, despite all the criticism levelled at the Johannesburg Biennale, it did offer opportunities to "travel Andries Botha, Dromedarls Donderl between people". -

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 Through October 31, 2007 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 through October 31, 2007 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS “Chapungu: Nature, Man, and Myth” presents 23 monumental, hand-carved stone sculptures of people, animals, and creatures of legend created by artists from the African nation of Zimbabwe, many from the Shona tribe. The exhibition illustrates a traditional African family’s attitude and close bond to nature, illustrating their interdependence in an increasingly complex world and fragile environment. How does this exhibition differ from the one the Missouri Botanical Garden hosted in 2001? All but one of the sculptures in this exhibition have never been displayed at the Missouri Botanical Garden. “Chapungu: Custom and Legend, A Culture in Stone” made its U.S. debut here in 2001. Two large sculptures from that exhibition were acquired by the Garden: “Protecting the Eggs” by Damian Manuhwa, and the touching “Sole Provider” by Joe Mutasa. Both are located in the Azalea-Rhodendron Garden, near the tram shelter. “Sole Provider” was donated by the people of Zimbabwe and Chapungu Sculpture Park in memory of those who died during the September 11, 2001 tragedy. An opal stone sculpture from the 2001 exhibition – Biggie Kapeta’s “Chief Consults With Chapungu”– returns as a preview piece, installed outside the Ridgway Center in January. Many artists from the 2001 exhibition are represented by other works this time. How do you say Chapungu? What does it mean? Say “Cha-POONG-goo.” Chapungu is a metaphor for the Bateleur Eagle (Terathopius ecaudatus), a powerful bird of prey that can fly up to 300 miles in a day at 30 to 50 miles per hour.