Adam Smith Real Newtonian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newton.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag

omslag Newton.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag. 1 e Dutch Republic proved ‘A new light on several to be extremely receptive to major gures involved in the groundbreaking ideas of Newton Isaac Newton (–). the reception of Newton’s Dutch scholars such as Willem work.’ and the Netherlands Jacob ’s Gravesande and Petrus Prof. Bert Theunissen, Newton the Netherlands and van Musschenbroek played a Utrecht University crucial role in the adaption and How Isaac Newton was Fashioned dissemination of Newton’s work, ‘is book provides an in the Dutch Republic not only in the Netherlands important contribution to but also in the rest of Europe. EDITED BY ERIC JORINK In the course of the eighteenth the study of the European AND AD MAAS century, Newton’s ideas (in Enlightenment with new dierent guises and interpre- insights in the circulation tations) became a veritable hype in Dutch society. In Newton of knowledge.’ and the Netherlands Newton’s Prof. Frans van Lunteren, sudden success is analyzed in Leiden University great depth and put into a new perspective. Ad Maas is curator at the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands. Eric Jorink is researcher at the Huygens Institute for Netherlands History (Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences). / www.lup.nl LUP Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 1 Newton and the Netherlands Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 2 Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. -

The Newton-Leibniz Controversy Over the Invention of the Calculus

The Newton-Leibniz controversy over the invention of the calculus S.Subramanya Sastry 1 Introduction Perhaps one the most infamous controversies in the history of science is the one between Newton and Leibniz over the invention of the infinitesimal calculus. During the 17th century, debates between philosophers over priority issues were dime-a-dozen. Inspite of the fact that priority disputes between scientists were ¡ common, many contemporaries of Newton and Leibniz found the quarrel between these two shocking. Probably, what set this particular case apart from the rest was the stature of the men involved, the significance of the work that was in contention, the length of time through which the controversy extended, and the sheer intensity of the dispute. Newton and Leibniz were at war in the later parts of their lives over a number of issues. Though the dispute was sparked off by the issue of priority over the invention of the calculus, the matter was made worse by the fact that they did not see eye to eye on the matter of the natural philosophy of the world. Newton’s action-at-a-distance theory of gravitation was viewed as a reversion to the times of occultism by Leibniz and many other mechanical philosophers of this era. This intermingling of philosophical issues with the priority issues over the invention of the calculus worsened the nature of the dispute. One of the reasons why the dispute assumed such alarming proportions and why both Newton and Leibniz were anxious to be considered the inventors of the calculus was because of the prevailing 17th century conventions about priority and attitude towards plagiarism. -

KAREN THOMSON CATALOGUE 103 UNIQUE OR RARE with A

KAREN THOMSON CATALOGUE 103 UNIQUE OR RARE with a Newtonian section & a Jane Austen discovery KAREN THOMSON RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE 103 UNIQUE OR RARE With a Newtonian section (1-8), and a Jane Austen discovery (16) [email protected] NEWTONIANA William Jones’ copy [1] Thomas Rudd Practicall Geometry, in two parts: the first, shewing how to perform the foure species of Arithmeticke (viz: addition, substraction, multiplication, and division) together with reduction, and the rule of proportion in figures. The second, containing a hundred geometricall questions, with their solutions & demonstrations, some of them being performed arithmetically, and others geometrically, yet all without the help of algebra. Imprinted at London by J.G. for Robert Boydell, and are to be sold at his Shop in the Bulwarke neer the Tower, 1650 £1500 Small 4to. pp. [vii]+56+[iv]+139. Removed from a volume of tracts bound in the eighteenth century for the Macclesfield Library with characteristically cropped inscription, running titles, catchwords and page numbers, and shaving three words of the text on H4r. Ink smudge to second title page verso, manuscript algebraic solution on 2Q3 illustrated below, Macclesfield armorial blindstamp, clean and crisp. First edition, one of two issues published in the same year (the other spelling “Practical” in the title). William Jones (1675-1749) was employed by the second Earl of Macclesfield at Shirburn Castle as his mathematics instructor, and at his death left his pupil and patron the most valuable mathematical library in England, which included Newton manuscript material. Jones was an important promoter of Isaac Newton’s work, as well as being a friend: William Stukeley (see item 6), in the first biography of Newton, describes visiting him “sometime with Dr. -

Cotton Mather's Relationship to Science

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 4-16-2008 Cotton Mather's Relationship to Science James Daniel Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, James Daniel, "Cotton Mather's Relationship to Science." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COTTON MATHER’S RELATIONSHIP TO SCIENCE by JAMES DANIEL HUDSON Under the Direction of Dr. Reiner Smolinski ABSTRACT The subject of this project is Cotton Mather’s relationship to science. As a minister, Mather’s desire to harmonize science with religion is an excellent medium for understanding the effects of the early Enlightenment upon traditional views of Scripture. Through “Biblia Americana” and The Christian Philosopher, I evaluate Mather’s effort to relate Newtonian science to the six creative days as recorded in Genesis 1. Chapter One evaluates Mather’s support for the scientific theories of Isaac Newton and his reception to natural philosophers who advocate Newton’s theories. Chapter Two highlights Mather’s treatment of the dominant cosmogonies preceding Isaac Newton. The Conclusion returns the reader to Mather’s principal occupation as a minister and the limits of science as informed by his theological mind. Through an exploration of Cotton Mather’s views on science, a more comprehensive understanding of this significant early American and the ideological assumptions shaping his place in American history is realized. -

Calculation and Controversy

calculation and controversy The young Newton owed his greatest intellectual debt to the French mathematician and natural philosopher, René Descartes. He was influ- enced by both English and Continental commentators on Descartes’ work. Problems derived from the writings of the Oxford mathematician, John Wallis, also featured strongly in Newton’s development as a mathe- matician capable of handling infinite series and the complexities of calcula- tions involving curved lines. The ‘Waste Book’ that Newton used for much of his mathematical working in the 1660s demonstrates how quickly his talents surpassed those of most of his contemporaries. Nevertheless, the evolution of Newton’s thought was only possible through consideration of what his immediate predecessors had already achieved. Once Newton had become a public figure, however, he became increasingly concerned to ensure proper recognition for his own ideas. In the quarrels that resulted with mathematicians like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) or Johann Bernoulli (1667–1748), Newton supervised his disciples in the reconstruction of the historical record of his discoveries. One of those followers was William Jones, tutor to the future Earl of Macclesfield, who acquired or copied many letters and papers relating to Newton’s early career. These formed the heart of the Macclesfield Collection, which has recently been purchased by Cambridge University Library. 31 rené descartes, Geometria ed. and trans. frans van schooten 2 parts (Amsterdam, 1659–61) 4o: -2 4, a-3t4, g-3g4; π2, -2 4, a-f4 Trinity* * College, Cambridge,* shelfmark* nq 16/203 Newton acquired this book ‘a little before Christmas’ 1664, having read an earlier edition of Descartes’ Geometry by van Schooten earlier in the year. -

The Birth of Calculus: Towards a More Leibnizian View

The Birth of Calculus: Towards a More Leibnizian View Nicholas Kollerstrom [email protected] We re-evaluate the great Leibniz-Newton calculus debate, exactly three hundred years after it culminated, in 1712. We reflect upon the concept of invention, and to what extent there were indeed two independent inventors of this new mathematical method. We are to a considerable extent agreeing with the mathematics historians Tom Whiteside in the 20th century and Augustus de Morgan in the 19th. By way of introduction we recall two apposite quotations: “After two and a half centuries the Newton-Leibniz disputes continue to inflame the passions. Only the very learned (or the very foolish) dare to enter this great killing- ground of the history of ideas” from Stephen Shapin1 and “When de l’Hôpital, in 1696, published at Paris a treatise so systematic, and so much resembling one of modern times, that it might be used even now, he could find nothing English to quote, except a slight treatise of Craig on quadratures, published in 1693” from Augustus de Morgan 2. Introduction The birth of calculus was experienced as a gradual transition from geometrical to algebraic modes of reasoning, sealing the victory of algebra over geometry around the dawn of the 18 th century. ‘Quadrature’ or the integral calculus had developed first: Kepler had computed how much wine was laid down in his wine-cellar by determining the volume of a wine-barrel, in 1615, 1 which marks a kind of beginning for that calculus. The newly-developing realm of infinitesimal problems was pursued simultaneously in France, Italy and England. -

A Catalogue of the Portsmouth Collection of Books

i^l^ BEQUEATHED BY LEONARD L. MACKALL 1879-1937 A.B., CLASS OF 1900 TO THE LIBRARY OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY 'Ci^! .y-" A CATALOGUE OF THE POETSMOUTH COLLECTION OF BOOKS AND PAPERS WRITTEN BY OB BELONGING TO SIK ISAAC NEWTON 0. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBEIDGE UNIVBESITY PEESS WAEEHOUSE, Ave Makia Lane. aiambtajse: DBIGHTON, BELL, AND CO. %npm- P- A. BEOCKHAUS. A CATALOGUE OP THE POETSMOUTH COLLECTION OF BOOKS AND PAPEES WEITTEN BX OE BELONGING TO SIE ISAAC NEWTON THE 8GIENTIPIC POETION OP WHICH HAS BEEN PEESBNTED BY THE EABL OP POETSMOUTH TO THE UNIVEESITY OP CAMBEIDGE DBAWN UP BY THE SYNDICATE APPOINTED THE 6th NOVEMBEE 1872 CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVEESITY PRESS 1888 Qdl so W\'~Z-/c . CAMBEIDGE: PKINTED BI ?. y, Bta-E, M.A. AND SONS, AT THE UNIVEESITY PRESS. MQUEATHEt, 3y LEdNARS L.. MACKA«, CONTENTS. Pbkfaoe ... ix Appendix to Pbefaoe . xxi CATALOGUE. SECTION I. PAGE Mathematics. I. Early papers by Newton . ... .1 n. Elementary Mathematics .... 2 m. Plnxions . ib. IV. Enumeration of Lines of the Third Order ib. V. On the Quadrature of Curves ... 3 VI. Papers relating 4o Geome4ry . , . ib. Vii. Miaeellaneous Mathematical subjects . .4 Vlil. Papers connected with the'Principia.' A. General . ib. LK. ,, „ ,^ ,, B. Lunar Theory . 5 X. „ „ „ „ 0. Ma4hematioal Problems 6 XI. Papers relating to the dispute respecting the invention of Fluxions ... ib. XTT. Astronomy ... .9 Xni. Hydrostatiea, Optics, Sound, and Heat . ib. XIV. MiacellaneouB copies of Lettera and Papere . 10 XV. Papera on finding the Longitude at Sea . ib. SECTION II. Ceemistby. *I. Parcela containing Transcripts from Alchemical authors 11 *II. -

'S Gravesande's and Van Musschenbroek's Appropriation Of

chapter 8 ’s Gravesande’s and Van Musschenbroek’s Appropriation of Newton’s Methodological Ideas Steffen Ducheyne 1 Introduction Willem Jacob ’s Gravesande (1688–1742) and Petrus van Musschenbroek (1692–1761) are rightfully considered as important trailblazers in the diffu- sion of Newtonianism on the Continent.1 They helped to establish teach- ing of Newton’s natural philosophy within the university curriculum and the textbooks which they wrote were of vital importance in its spread and popularization.2 On the face of it, there are good reasons for portraying ’s Gravesande and van Musschenbroek as “Newtonians”. Both ’s Gravesande and van Musschenbroek spent time in England where they became acquainted † Parts of this chapter was presented at the international conference “The Reception of Newton” (Edward Worth Library, Dublin, 12–13 July 2012). The author is indebted to its au- dience for useful suggestions. In this chapter I draw extensively on material from Steffen Ducheyne, “W.J. ’s Gravesande’s Appropriation of Newt on’s Natural Philosophy, Part i: Episte- mological and Theological issues”, Centaurus, 56(1) (2014), 31–55; id., “W.J. ’s Gravesande’s Ap- propriation of Newton’s Natural Philosophy, Part ii: Methodological Issues”, Centaurus, 56 (2) (2014), 97–120; id., “Petrus van Musschenbroek and Newton’s ‘vera stabilisque Philosophandi methodus’”, Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 38 (4) (2015), 279–304; and id., “Petrus van Musschenbroek on the scope of physica and its place in philosophy”, Asclepio, Revista de his- toria de la medicina y de la ciencia, 68, no. 1 (2016) article no 123. 1 John Gascoigne, “Ideas of Nature”, in Roy Porter (ed.), The Cambridge History of Science, Vol- ume 4: Eighteenth-Century Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 285–304; 297–299; Edward G. -

James Stirling: Mathematician and Mine Manager

The Mathematical Tourist Dirk Huylebrouck, Editor James Stirling: lthough James Stirling enjoyed a substantial reputa- tion as a mathematician among his contemporaries in AA Britain and in some other European countries, he Mathematician published remarkably little after his book Methodus Differ- entialis: sive Tractatus de Summatione et Interpolatione and Mine Manager Serierum Infinitarum in 1730. An article with valuable information on the achievements of James Stirling during his time as mine manager in Scotland appeared in the Glasgow ARITZ P. M Herald of August 3, 1886, see [8]. The Herald article was reprinted in Mitchell’s The Old Glasgow Essays of 1905 [7]. Detailed accounts of Stirling’s mathematical achievements and correspondences with his contemporaries can be found Does your hometown have any mathematical tourist in [12, 13], and [14]. attractions such as statues, plaques, graves, the cafe´ The Stirlings and Their Estates where the famous conjecture was made, the desk where James Stirling was the third son of Archibald Stirling (March 21, 1651 - August 19, 1715) of the estate Garden (about the famous initials are scratched, birthplaces, houses, or 20 km west of Stirling) in the parish of Kippen, Stirling- shire, Scotland. memorials? Have you encountered a mathematical sight In 1180, during the reign of King William I of Scotland, a Stirling acquired the estate of Cawder in Lanarkshire, and it on your travels? If so, we invite you to submit an essay to has been in the possession of the family ever since. Sir this column. Be sure to include a picture, a description Archibald Stirling (1618 - 1668) was a conspicuous Royalist in the Civil War, and was heavily fined by Cromwell; but his of its mathematical significance, and either a map or loyalty was rewarded at the Second Restoration (1661), and he ascended the Scottish bench with the title of Lord Gar- directions so that others may follow in your tracks. -

Isaac Newton's Temple of Solomon and His Reconstruction of Sacred Architecture

Isaac Newton's Temple of Solomon and his Reconstruction of Sacred Architecture Bearbeitet von Tessa Morrison 1. Auflage 2010. Buch. xix, 186 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 0348 0045 7 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 517 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Kunst, Architektur, Design > Architektur: Allgemeines > Geschichte der Architektur, Baugeschichte Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Chapter 2 Chronology, Prisca Sapientia and the Temple Apart from Reports as Master of the Mint, which were published between 1701 and 1725, Newton published only scientific manuscripts in his lifetime. Principia pub- lished in 1687, which consisted of three volumes, defined the three laws of motion and gravitation which lay down the foundation of classical mechanics, and in the formation of this theory he developed the mathematical field of calculus. Newton added material and revised the Principia in 1713 and 1726. His second contribution to science was Opticks, which considered the properties and the refraction of light, and was published in 1704. These two books had established Newton as the most significant scientist of his time. However, science was not his only interest and in fact Newton’s library consisted of only 52 volumes, or 3% of the whole library, on mathematics, physics and optics.67 At the time of Newton’s death, his library consisted of approximately 2100 volumes of which 1763 had been accounted for in a study made by John Harrison published 1978.68 Newton did not make inventories of his library as was the fashion of the day by professional book collectors69; his books were working books – tools. -

The Scottish Enlightenment and Descartes's Philosophical Novel

The Scottish Enlightenment and Descartes’s philosophical novel* Sergio Cremaschi 1. Scottish Newtonianism During the first half of the eighteenth century, Newton's work became the emblem of the "new philosophy" all over Europe. It provided a model to be followed in every field, and the divide between the friends and the enemies of Reason. Reasons for such a sanctification of Newton are to be found primarily in the end, due to the competitor’s disappearance, of the polemics against Aristotelianism, which with its sequel of occult qualities and substantial forms had provided seventeenth century philosophers an excellent straw-man. Secondly, they are to be found in the birth of a controversy between Cartesians and Newtonians. This controversy will grow with a snow-ball effect, starting with a purely scientific issue, namely the theory of vortices, coming to include two overall views of scientific method and two distinct theories of knowledge. Thus, at the very interest in attacking Aristotle vanished, as Aristotelianism ceased being perceived as a real danger, the villain became Descartes, the author of an "illusive philosophy" or of "one of the most entertaining romances that have ever been wrote". The Scottish Enlighteners were those who made the most of Newton's legacy, since (i) they most firmly believed in the need to apply the Newtonian method to every field, not only to natural philosophy, but also to a restructuring of practical philosophy which should yield the (never launched) new science of natural jurisprudence, and (ii) they had the strongest reasons to contrast Newton with Descartes, since the Scots' Newtonianism was not the Platonic Newtonianism of Cambridge physico-theologians, but an experimental and even (ironic as this may be) anti- mathematical Newtonian tradition (partly imported from the Netherlands) Let me add a few words on the first point, i.e., the idea of a Moral Newtonianism. -

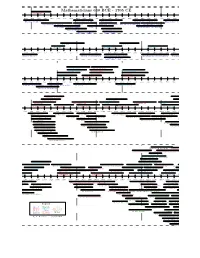

Mathematicians Timeline

Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold Sergey Bernstein Gotthold Eisenstein Edmund Landau Issai Schur Leoplod Kronecker Paul Halmos Hermann Minkowski Hermann von Helmholtz Paul Erd}os Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Vladimir Steklov Karl Weierstrass Kurt G¨odel Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Andrei Markov Ernst Eduard Kummer Alexander Grothendieck Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Sofia Kovalevskya Andrey Kolmogorov Moritz Stern Friedrich Hirzebruch Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Georg Cantor Carl Goldschmidt Ferdinand von Lindemann Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Pafnuti Chebyshev Oscar Zariski Carl Gustav Jacobi F Georg Frobenius Peter Lax Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Solomon Lefschetz Julius Pl¨ucker Hermann Weyl Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Karl von Staudt Eugene Wigner Martin Ohm Emil Artin Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold August Ferdinand