Construction USE by ALL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01 Bagerhat Zila Total 1476090 1.7 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.7 0.2 0.1 01 1

Table C-09: Percentage Distribution of Population by Type of disability, Residence and Community Administrative Unit Type of disability (%) UN / MZ / Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence WA MH Population Community All Speech Vision Hearing Physical Mental Autism 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 01 Bagerhat Zila Total 1476090 1.7 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.7 0.2 0.1 01 1 Bagerhat Zila 1280759 1.8 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.8 0.2 0.1 01 2 Bagerhat Zila 110651 1.4 0.1 0.3 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 01 3 Bagerhat Zila 84680 1.7 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.7 0.2 0.1 01 08 Bagerhat Sadar Upazila Total 266389 1.4 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1 01 08 1 Bagerhat Sadar Upazila 217316 1.5 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.7 0.2 0.1 01 08 2 Bagerhat Sadar Upazila 49073 0.9 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.1 01 08 Bagerhat Paurashava 49073 0.9 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.1 01 08 01 Ward No-01 Total 5339 1.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.0 01 08 02 Ward No-02 Total 5406 0.8 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.2 0.2 0.1 01 08 03 Ward No-03 Total 7688 1.2 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.6 0.1 0.1 01 08 04 Ward No-04 Total 4530 1.3 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.3 0.2 01 08 05 Ward No-05 Total 4297 0.6 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.3 0.1 0.0 01 08 06 Ward No-06 Total 3869 0.7 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.1 0.3 01 08 07 Ward No-07 Total 5210 0.9 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 0.1 01 08 08 Ward No-08 Total 7394 0.5 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.2 01 08 09 Ward No-09 Total 5340 1.2 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.3 0.1 01 08 17 Barai Para Union Total 25610 1.9 0.2 0.2 0.2 1.0 0.2 0.1 01 08 25 Bemarta Union Total 24595 1.5 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.6 0.3 0.1 01 08 34 Bishnupur Union Total 21593 1.2 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.6 0.2 0.0 01 08 35 Dema Union Total 15777 1.5 0.2 0.3 0.1 0.7 0.2 0.1 01 08 51 Gota Para -

Cyclone Contigency Plan for Karachi City 2008

Cyclone Contingency Plan for Karachi City 2008 National Disaster Management Authority Government of Pakistan July 2008 ii Contents Acronyms………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..iii Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………....iv General…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Aim………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Scope…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Tropical Cyclone………………………………………………………………………………………..……………….2 Case Studies Major Cyclones………………………..……………………………………… ……………………….3 Historical Perspective – Cyclone Occurrences in Pakistan…...……………………………………….................6 General Information - Karachi ….………………………………………………………………………………….…7 Existing Disaster Response Structure – Karachi………………………. ……………………….…………….……8 Scenarios for Tropical Cyclone Impact in Karachi City ……………………………………………………….…..11 Scenario 1 ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..11 Scenario 2. ……………………………………………………………………………………………….….13 Response Scenario -1…………………… ……………………………………………………………………….…..14 Planning Assumptions……………………………………………………………………………………....14 Outline Plan……………………………………………………………………………………………….….15 Pre-response Phase…………………………………………………………………………………….… 16 Mid Term Measures……………………………………………………………………..………..16 Long Term Measures…………………...…………………….…………………………..……...20 Response Phase………… ………………………..………………………………………………..………21 Provision of Early Warning……………………. ......……………………………………..……21 Execution……………………….………………………………..………………..……………....22 Health Response……………….. ……………………………………………..………………..24 Coordination Aspects…………………………………………….………………………...………………25 -

Working Paper 298

WORKING PAPER 298 IDS_Master Logo Taking Community-Led Total Sanitation to Scale: Movement, Spread and Adaptation Andrew Deak February 2008 IDS_Master Logo_Minimum Size X X Minimum Size Minimum Size X : 15mm X : 15mm About IDS The Institute of Development Studies is one of the world's leading organisations for research, teaching and communications on international development. Founded in 1966, the Institute enjoys an international reputation based on the quality of its work and the rigour with which it applies academic skills to real world challenges. Its purpose is to understand and explain the world, and to try to change it – to influence as well as to inform. IDS hosts five dynamic research programmes, five popular postgraduate courses, and a family of world- class web-based knowledge services. These three spheres are integrated in a unique combination – as a development knowledge hub, IDS is connected into and is a convenor of networks throughout the world. The Institute is home to approximately 80 researchers, 50 knowledge services staff, 50 support staff and about 150 students at any one time. But the IDS community extends far beyond, encompassing an extensive network of partners, former staff and students across the development community worldwide. IDS_Master Logo Black IDS_Master Logo_Minimum Size X X Minimum Size Minimum Size X : 15mm X : 15mm For further information on IDS publications and for a free catalogue, contact: IDS Communications Unit Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex Brighton BN1 9RE, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1273 678269 Fax: +44 (0) 1273 621202 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ids.ac.uk/ids/bookshop IDS is a charitable company, limited by guarantee and registered in England (No. -

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Esdo Profile

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) 1. Background Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

Medicinal Plants Used by the Village Pania Under Baghmara District

ANALYSISANALYSIS ARTICLE 54(266), February 1, 2018 ISSN 2278–5469 EISSN 2278–5450 Discovery Medicinal plants used by the local people at the village Pania under Baghmara Upazila of Rajshahi District, Bangladesh Mst. Mafroja Khatun, Mahbubur Rahman AHM☼ Plant Taxonomy Laboratory, Department of Botany, Faculty of Life and Earth Sciences, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi-6205, Bangladesh ☼Corresponding Author: Professor, Department of Botany, Faculty of Life and Earth Sciences, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi-6205, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Phone: 880 721 751485, Mobile: 88 01714657224 Article History Received: 29 November 2017 Accepted: 2 January 2018 Published: 1 February 2018 Citation Mst. Mafroja Khatun, Mahbubur Rahman AHM. Medicinal plants used by the local people at the village Pania under Baghmara Upazila of Rajshahi District, Bangladesh. Discovery, 2018, 54(266), 60-71 Publication License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. General Note Article is recommended to print as color digital version in recycled paper. Save trees, save nature ABSTRACT 6060 60 Medicinal plants used by the local people at the village Pania under Baghmara upazila of Rajshahi district, Bangladesh was carried out from December 2016 to November 2017. A total of 56 species belonging to 52 genera under 39 families were recorded. PagePage Page © 2018 Discovery Publication. All Rights Reserved. www.discoveryjournals.org OPEN ACCESS ANALYSIS ARTICLE Magnoliopsida is represented by 33 family, 46 genera and 49 species and Liliopsida is represented by 6 family 6 genera and 7 species. For each species botanical name, local name, habit, parts used, ailments, treatment process and family were provided. -

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

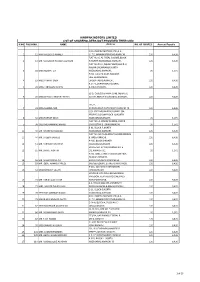

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

Material Culture from the Wilson Farm Tenancy: Artifact Analysis

AT THE ROAD’S EDGE: FINAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE WILSON FARM TENANCY SITE 7 Material Culture from the Wilson Farm Tenancy: Artifact Analysis LABORATORY AND ANALYTICAL METHODS The URS laboratory in Burlington, New Jersey, processed the artifacts recovered from Site 7NC- F-94. All artifacts were initially cleaned, labeled, and bagged (throughout, technicians maintained the excavation provenience integrity of each artifact). Stable artifacts were washed in water with Orvis soap using a soft bristle brush, then air-dried; in some cases, on an individual basis, artifacts deemed too delicate to wash were dry brushed—this is often the case with badly deteriorated iron and bone objects considered noteworthy. Technicians then labeled items such as prehistoric lithics, historic ceramics, bone, glass, and some metal artifacts. Labeling was conducted using an acid free, conservation grade, .25mm Staedtler marking pen applied over a base coat of Acyloid B72 resin; once the ink dried, the label was sealed with a second layer of Acyloid B72. The information marked on the artifacts consisted of the provenience catalog number. Once the artifacts were processed, they were then inventoried in a Microsoft Access database. The artifacts were sorted according to functional groups and material composition in this inventory. Separate analyses were conducted on the artifacts and inventory data to answer site spatial and temporal questions. Outside consultants analyzed the floral and faunal materials. URS conducted soil flotation. In order to examine the spatial distributions of artifacts in the plowzone, we entered the data for certain artifact types into the Surfer 8.06.39 contouring and surface-mapping program. -

Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport

Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport A Case Report: Faisalabad, Pakistan Atta Ullah Khan assisted by Wajid Hassan Edited by M. Sohail Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University 2003 Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University Leicestershire LE11 3TU UK © WEDC, Loughborough University, 2003 Any part of this publication, including the illustrations (except items taken from other publications where the authors do not hold copyright) may be copied, reproduced or adapted to meet local needs, without permission from the author/s or publisher, provided the parts reproduced are distributed free, or at cost and not for commercial ends, and the source is fully acknowledged as given below. Please send copies of any materials in which text or illustrations have been used to WEDC Publications at the address given above. Atta Ullah Khan assisted by Wajid Hassan (2003) Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport - A Case Report: Faisalabad, Pakistan Series Editor: M. Sohail A reference copy of this publication is also available online at: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/wedc/publications/piaqpt-pakistan ISBN Paperback 1 84380 038 1 This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of low-income countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Designed and produced at WEDC by Glenda McMahon, Sue Plummer and Rod Shaw List of maps and figures Map 1.1. Faislabad: Land use map ....................................................................4 Map 1.2. Location of Katchi Abadies ..................................................................6 Map 2.1. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :URBAN STATE : JAMMU & KASHMIR DISTRICT : Anantnag Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL HUSBANDRY NAZ BASTI ANTNTNAG OPPOSITE TO SADDAR POLICE STATION ANANTNAG PIN CODE: 2000 10 - 50 192102, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 2 ASSTSTANT SERICULTURE OFFICER NAGDANDY , PIN CODE: 192201, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 1985 10 - 50 3 INTENSIVE POULTRY PROJECT MATTAN DTSTT. ANANTNAG , PIN CODE: 192125, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: 1988 10 - 50 NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0140-Agricultural and animal husbandry service activities, except veterinary activities. 4 DEPTT, OF HORTICULTURE KULGAM TEH KULGAM DISTT. ANANTNAG KASHMIR , PIN CODE: 192231, STD CODE: NA , 1969 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 5 DEPTT, OF AGRICULTURE KULGAM ANANTNAG NEAR AND BUS STAND KULGAM , PIN CODE: 192231, STD CODE: NA , 1970 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0200-Forestry, logging and related service activities 6 SADU NAGDANDI PIJNAN , PIN CODE: 192201, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : 1960 10 - 50 N.A. 7 CONSERVATOR LIDDER FOREST CONSERVATOR LIDDER FOREST DIVISION GORIWAN BIJEHARA PIN CODE: 192124, STD CODE: 1970 10 - 50 DIVISION NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A.