Working Paper 298

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Material Culture from the Wilson Farm Tenancy: Artifact Analysis

AT THE ROAD’S EDGE: FINAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE WILSON FARM TENANCY SITE 7 Material Culture from the Wilson Farm Tenancy: Artifact Analysis LABORATORY AND ANALYTICAL METHODS The URS laboratory in Burlington, New Jersey, processed the artifacts recovered from Site 7NC- F-94. All artifacts were initially cleaned, labeled, and bagged (throughout, technicians maintained the excavation provenience integrity of each artifact). Stable artifacts were washed in water with Orvis soap using a soft bristle brush, then air-dried; in some cases, on an individual basis, artifacts deemed too delicate to wash were dry brushed—this is often the case with badly deteriorated iron and bone objects considered noteworthy. Technicians then labeled items such as prehistoric lithics, historic ceramics, bone, glass, and some metal artifacts. Labeling was conducted using an acid free, conservation grade, .25mm Staedtler marking pen applied over a base coat of Acyloid B72 resin; once the ink dried, the label was sealed with a second layer of Acyloid B72. The information marked on the artifacts consisted of the provenience catalog number. Once the artifacts were processed, they were then inventoried in a Microsoft Access database. The artifacts were sorted according to functional groups and material composition in this inventory. Separate analyses were conducted on the artifacts and inventory data to answer site spatial and temporal questions. Outside consultants analyzed the floral and faunal materials. URS conducted soil flotation. In order to examine the spatial distributions of artifacts in the plowzone, we entered the data for certain artifact types into the Surfer 8.06.39 contouring and surface-mapping program. -

Fowler College of Business Career Fair 2018 / Employers

2018 FOWLER COLLEGE OF BUSINESS CAREER FAIR THE FOWLER COLLEGE OF BUSINESS MARCH 15, 2018 CAREER FAIR IS YOUR OPPORTUNITY TO NETWORK WITH RECRUITERS LOOKING TO FILL FULL-TIME, PART-TIME, AND 10:00AM - 2:30PM INTERNSHIP POSITIONS. FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION SAN DIEGO STATE UNIVERSITY DOWNLOAD THE APP SYMPLICITY JOBS AND CAREERS. CONRAD PREBYS AZTEC STUDENT UNION MONTEZUMA HALL DRESS TO IMPRESS!!! TAKE A Register here: https://goo.gl/fSsZNJ COMPLIMENTARY HEADSHOT FOR YOUR LINKEDIN PROFILE! Questions? Contact Michelle Svay [email protected] 619.594.0435 Fowler College of Business Career Fair 2018 / Employers E M P L O Y E R P A G E E M P L O Y E R P A G E 10Fold Communications 2 Northwestern Mutual 15 3Q Digital 2 OneMain Financial 15 Aerotek 2 PayLease 16 Aflac 2 PepsiCo 16 ALDI Inc. 3 Prudential Advisors 16 ArcBest 3 Rehab United Sports Medicine & Physical Therapy 16 AXA Advisors,LLC 4 San Diego Gas and Electric 17 Bankers Life 4 Seamgen 17 California Department of Tax and Fee Administration 4 ServiceNow 17 Chamberlain Group 4 Sharp HealthCare 17 CHARTER COMMUNICATIONS 5 Sherwin-Williams 18 Cobham 5 South Coast Copy Systems 18 Collabera 5 Stanley Black & Decker 18 Consolidated Electrical Distributors, Inc. 5 Tang Capital Management, LLC 18 Corelation Inc 6 The Hershey Company 19 Cox Enterprises 6 The Princeton Review 19 Crystal Equation 6 The Select Group 19 Defense Contract Audit Agnecy 6 Thrivent Financial 19 DHL Express 7 Title Resource Group 20 E&J Gallo Winery 7 TOYOTA 20 EcoShield Pest Control 7 Treloar & Heisel, Inc. -

GARAGE SALES Kets, Pottery, Antique Prints & Frame Prints, Furniture, Aladin & Mid Century Modern Lamps, Glass Baskets, Lead Milford Crystal and Many Misc Items

THE Milford LakesTHE News Shopper 710 Okoboji Ave, Mil- ford. Fri & Sat, Sept 3 & 4, 10am - 5pm. Large multi party garage sale. Lots of vintage and antique items, LAKES NEWS SHOPPERglassware, books, vintage picnic bas- GARAGE SALES kets, pottery, antique prints & frame prints, furniture, Aladin & mid century modern lamps, glass baskets, lead Milford crystal and many misc items. 1201 10th St, Milford. Fri, 9am-7pm. Sat, 8am-1pm. Large multi family garage sale. Name-brand baby Raising Funds for thru plus-size clothes, outerwear, boots/ shoes, some home items, lots of $1 items. Accepting cash, debit & credit cards. 1211 10th St, Milford. Fri, Sept 3, 9am-5pm, and Sat, Sept 4, 8am -12pm. Tools, fishing, Transforming Lives, lighting, household hardware, wooden Strengthening Families cabinets, glassware, misc items, nails. Formerly Thee Garage Sale 1109 6th St, Milford. Sept 4 and 5, All day. Camping, fishing, and New Look, Same Great rope. Yard and garage tools. House People & Services! goods and much more. Huge sale! Part Time 2072 220th St, Milford. 1-46c SHOP OFTEN … New Sat Sept 4th, 9-5 and Sun, Sept 5th, Inventory Arrives Daily! 9-5. 1.4 miles west of Catholic Church. Help Wanted We have a lot more of nice women’s We Carry Furniture, Collectibles, clothing and shoes, kids clothing and Apply in person Gifts, Sporting, Household, Baby shoes more decor, and antiques, nice Items & So Much More! prints, old books, bicycle with a gas power engine and a lot of misc clean- For more information, Talk to Store Manager Warren Jager ing out the barns!! Never know what visit www.cherishcenter.org about becoming a volunteer. -

Auction Catalog

AUCTION CATALOG Los Angeles County Treasurer & Tax Collector & Public Administrator Estate Auction Saturday, January 11th at 9am 16610 Chestnut St., City of Industry, CA 91748 Register Early Online at cwsmarketing.com Preview Day of Sale Beginning at 7:30am Simulcast Bidding on Vehicles & Select Lots FEATURING Autos, 1,000+ Gold & Silver Coins Gold & Costume Jewelry, Watches 1000’s of Collectibles & Smalls, Art 100’s Antique, Vintage & Newer Furniture Pcs. Books, Records, Tools, Electronics, Household Items Please visit our website for detailed listing and photos. www.cwsmarketing.com 888-343-1313 x 256 Sale conducted by CWS Asset Management & Sales, Sean Fraley Auctioneer ORDER OF SALE Thank you for attending today’s auction. All property for sale is being offered by the Los Angeles County Public Administrator and comes from various estates within Los Angeles County. Below is the general order of sale. Two or auction rings are conducted simultaneously, with each beginning at 9:00am and continuing numerically throughout the day. Register Prior to Sale Day at www.cwsmarketing.com Sale Start Times: Preview 7:30am (Preview continues until each section is being sold) Auction Start 9:00am Three Simultaneous Auctions Auction Ring #1 (All Times Approximate) 9:00am: Automobiles Simulcast Bidding Available 9:00am: Household Furniture, Accessories, Boxes of Art & Misc. Household 10:00am: Antique, Vintage & Modern Furniture and Accessories 11:00am: Bric-A-Brac (Bulk household box lots & Clothing) 12:00am: Appliances, Electronics, Computers, Tools, Recreation & Misc. Auction Ring #’s 2 & 3 (All Times Approximate) 9:00am: Books, Records, CD’s, DVD’s, Videos and Misc. 10:00am: Collectibles, Art, Smalls Box-Lots & Specialty Auction Ring # 3 (All Times Approximate) 11:00am: Jewelry, Coins, Currency & Specialty Items Simulcast Bidding Available Buyer’s Premium: A 15% Buyer’s Premium is added to the bid price of each lot. -

Noiseless, Automatic Service: the History of Domestic Servant Call Bell Systems in Charleston, South Carolina, 1740-1900

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2013 Noiseless, Automatic Service: The iH story of Domestic Servant Call Bell Systems in Charleston, South Carolina, 1740-1900 Wendy Danielle Madill Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Madill, Wendy Danielle, "Noiseless, Automatic Service: The iH story of Domestic Servant Call Bell Systems in Charleston, South Carolina, 1740-1900" (2013). All Theses. 1660. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1660 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOISELESS, AUTOMATIC SERVICE: THE HISTORY OF DOMESTIC SERVANT BELL SYSTEMS IN CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, 1740-1900 A Thesis Presented to The Graduate School of Clemson University and College of Charleston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Wendy Danielle Madill May 2013 Accepted by: Dr. Carter L. Hudgins, Committee Chair Elizabeth Garrett Ryan Richard Marks, III ABSTRACT Shortly before Europe’s industrial revolution, tradesmen discovered an ingenious way to rig bells in houses to mechanize communication between homeowners and their servants. Mechanical bell systems, now known as house bells or servant call bells, were prevalent in Britain and America from the late 1700s to the early twentieth century. These technological ancestors of today’s telephone were operated by the simple pull of a knob or a tug of a tassel mounted on an interior wall. -

Resurging Asian Giants: Lessons from the People’S Republic of China and India

Resurging Asian Giants: Lessons from the People’s Republic of China and India The economies of the People’s Republic of China and India have seen dramatic growth in recent years. As their respective successes continue to Asian Giants: Resurging reshape the world’s economic landscape, noted Chinese and Indian scholars have studied the two countries’ development paths, in particular their rich and diverse experiences in such areas as education, information technology, local entrepreneurship, capital markets, macroeconomic management, foreign direct investment, and state-owned enterprise reforms. Drawing on these studies, the Asian Development Bank has produced a timely collection of lessons learned that serves as a valuable refresher on the challenges and opportunities ahead for developing economies, especially those in Asia and the Pacific. About the Asian Development Bank Lessons from the People’s Republic of China and India Republic Lessons from the People’s ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries substantially reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, Resurging Asian Giants environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the Lessons from the People’s Republic of China and India region. -

Philips Lamps and Lighting Solutions Retail List

Philips lamps and lighting solutions Retail list Philips LED lamps are available for purchase in most major supermarket chains and selected DIY stores in Singapore. Philips home lighting range is available for purchase at Light Lab by Philips Lighting, Philips Lighting partner stores and selected DIY stores in Singapore. Light Lab by Philips Lighting 622 Lorong 1 Toa Payoh, Philips APAC Center Level 1, Singapore 319763 Email: [email protected] Visit Light Lab by Philips Lighting to experience and learn more about Hue or speak with our smart lighting assistant via FB messenger. Operating hours: Mondays to Fridays 9am–6pm, Saturdays 9am–1pm. Closed on Sundays & Public Holidays Philips Lighting partner stores Bukit Merah 161 Bukit Merah Central #01-3707, Singapore 160161. Tel: 6271 2498 Geylang 722 Geylang Road, Singapore 389633. Tel: 6848 4613 Jalan Berseh 1 Jalan Berseh, New World Center, #01-16/17, Singapore 209037. Tel: 6299 5358 Jurong Boon Lay Way, Trade Hub 21, #01-51/52, Singapore 609965. Tel: 6793 0392 Ubi 33 Ubi Ave 3, Vertex #01-73. Singapore 408868. Tel: 6256 0080 Yishun Blk 102 Yishun Ave 5 #01-129, Singapore 760102. Tel: 6257 2428 List of other stores that retails Philips lamps and lighting solutions. Check out our partner stores nearest to you. Kindly note that stores listed below may not carry the full range of Philips Lighting products Stores selling LED lamps (bulbs, spots and candles), battens, tubes, downlights and ceiling lights Central 123 Budget Shop Blk 462 Commonwealth Dr #01-378, Singapore 140462 5 Star -

Rubber Band Engineer Build Slingshot Powered Rockets Rubber Band Rifles Unconventional Catapults and More Guerrilla Gadgets from Household Hardware by Lance Akiyama

Rubber Band Engineer Build Slingshot Powered Rockets Rubber Band Rifles Unconventional Catapults and More Guerrilla Gadgets from Household Hardware by Lance Akiyama You're readind a preview Rubber Band Engineer Build Slingshot Powered Rockets Rubber Band Rifles Unconventional Catapults and More Guerrilla Gadgets from Household Hardware book. To get able to download Rubber Band Engineer Build Slingshot Powered Rockets Rubber Band Rifles Unconventional Catapults and More Guerrilla Gadgets from Household Hardware you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited ebooks*. Accessible on all your screens. *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every file is in the library. But if You are still not sure with the service, you can choose FREE Trial service. Ebook Details: Review: Am planning to purchase approx. 20 more as Christmas Gifts, plus his other books for myself, (hope this doesnt ruin anyones Christmas surprise). Have mine on the coffee table and thus far three people have read it from cover to cover prior to my getting a chance. Amazing concepts and even better, they really work ! Can not wait to read more books... Original title: Rubber Band Engineer: Build Slingshot Powered Rockets, Rubber Band Rifles, Unconventional Catapults, and More Guerrilla Gadgets from Household Hardware Series: Engineer 144 pages Publisher: Rockport Publishers (May 15, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 9781631591044 ISBN-13: 978-1631591044 ASIN: 1631591045 Product Dimensions:8.6 x 0.6 x 10 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 17256 kB Ebook Tags: year old pdf, rubber bands pdf, book full pdf, projects pdf, project pdf, build pdf, materials pdf, photos pdf, science pdf, building Description: You dont have to be a genius to create these ingenious contraptions, you just need rubber bands, glue, paperclips, and Rubber Band Engineer, of course.Shooting far, flying high, and delivering way more exciting results than expected are the goals of the gadgets in Rubber Band Engineer. -

Karis Gladly Accepts New and Gently Used Clean Items That Are Not Chipped, Dented, Or Broken

Karis gladly accepts new and gently used clean items that are not chipped, dented, or broken. No soiled, worn, or faded furniture will be accepted. Individual items must have a resale value of $5 or more. Items under that value can be donated to Karis. Consignment items NOT accepted: All Linens Individual Mugs, Cups, Saucers Appliances Lamp Shades Artificial Floral Arrangements Luggage ¾ Beds Mantels Baby Items, Furniture, Cradles Magazine Racks Books Milk Glass Items Candles Mirrors Children’s Toys, Dolls, Games, Furniture Monogram Items China Sets over $95 Office furniture/ equipment Clothing/Footwear Plug-in items except lamps Collector Plates Quilt Racks Computer Desks/Large Desks Picture Frames/Prints without Frames DVDs/Cassette Tapes/Albums Pocketbooks Electronics Punch Bowl Sets Entertainment Centers Rugs larger than 5x7 Exercise/Sports Equipment School Desks Fabric Wall Hangings Sleep Sofas Florist Vases Snack Sets Flush Mounted Lights Toiletries Hanging Shelves, Sconces Travel Mugs Headboards w/o frames Wrist Watches Household Hardware/Window Hardware Additional Consignment Guidelines: • Bar Stools/Wooden Straight Chairs – • Dinnerware and Glasses – sets of sets of two or more four or more • Baskets – only handmade such as • Pictures – must hang Longaberger • Seasonal items – only accepted • Clocks – working with batteries during applicable season –refer to • Lamps – working w/clean shade website for details • Rugs – consignor must unroll rug to be inspected and then reroll rug with the topside out Karis reserves the right to reject any item and to make changes to this list without notice. 2465 Lee Highway, Mt. Sidney, VA [email protected] (540) 248-4511 Updated: January 2020 . -

Virtual Power Station 2.0

2014/RND032 VIRTUAL POWER STATION 2.0 Project results and lessons learnt Lead organisation: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). Project commencement date: October 2014 Completion date: January 2018 Date published: January 2018 Contact name: Chris Knight Title: Senior Research Engineer Email: [email protected] Phone: +61 2 4960 6049 Website: https://www.csiro.au/en/Research/EF/Areas/Electricity-grids-and-systems/Intelligent- systems/Virtual-power-station 1 Summary The increasing uptake of both solar PV and battery systems poses a serious risk of exceeding the hosting capacity of many Australian distribution network segments. Large amount of uncoordinated solar PV and battery systems can result in so called ‘power quality’ problems, with unacceptably high and fluctuating voltages, an inability to export to grid at times, and restrictions placed on the proportion of energy sourced from PV. Many existing energy-optimization solutions provide benefits to only one party: typically either the customer or the distribution network service provider (DNSP). The purpose behind the Virtual Power Station 2.0 (VPS2) project, by contrast, was to develop a moderately-priced solution that delivers balanced technical and economic benefits for all parties (customers, DNSPs and society). The solution leverages controllable PV, batteries, and loads (air-conditioners) to first optimise on-site electricity supply and demand and then aggregates customer-devices to deliver optimal solutions for the network as a whole. Building upon CSIRO’s seminal Virtual Power Station (VPS) research, this project examined: 1. On-Site Supply & Demand Co-Ordination: Development of an integrated control system for coordinating major appliance loads, energy storage, solar export and reactive power within residential and small commercial sites. -

Public Auctions Public Auctions

18 Greater Reading Area Merchandiser W - March 9, 2016 Audited PUBLIC AUCTIONS Coverage THE KEY TO THRIFTY BUYING 03-26-16: Farm Equipment, Tools, 04-16-16: Real Estate, 2 tracts of prime Tractors. Sale for local farmers, located farm land. Sale for Irene Trexler Estate, You Can Keep Up With the latest Public PUBLIC AUCTION at 1126 Moselem Spring R oad, , located at 57 Jalappa Road, Hamburg. Hamburg. Kenneth Leiby and Brian Gels- Wagner Auction Service, Auctioneers. Sales online at themerchandiser.com LISTINGS inger, Auctioneers. 03-28-16: Real Estate. Sale for Laverne 03-12-16: 8:30am, 11:30am & 1pm. An- M & Rhoda B. Hurst, located at 78 Cross Auction Terms tiques, Collectibles, Farm Equipment, Key Road, Bernville, Pa. 19506, Martin & Household, Lawn & Garden, Real Estate, Rutt Auctioneers. Trustee’s Sale 2 ESTATE SALES & Sandstone Home & barn or 13.235 acres. A sale at auction by a trustee. 1 ONLINE AUCTION Sale for Roy A. Kurtz & Judith Ressler, 04-07-16: 6 PM. Real Estate. Sale for PDA, 720 Fairmont Avenue, Mohnton Dorothy M. Beavens, 372 Preston Rd. (Clinton Township, Becks County) Art Wernersville. Art Pennypacker/ Brad Tie Bids Pannebecker, Auctioneer. Wolf, Auctioneer. When two or more bidders bid 03-12-16: Antiques, Collectibles. Locat- exactly the same amount at the ed at 1251 Chestnut Street, Reading. 04-08-16: 6 PM. Real Estate. Sale for Sat. Mar. 12th & Sun. Mar. 13th: Estate Sale & Online Auction Preview Renaissance Auction Group, Auctioneers. David C. & Christine L. Walters. 80 same time and must be resolved 1251 Chestnut St., Reading: Sat. -

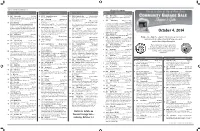

October 4, 2014 Find Something You Can Enjoy

listings Continued from previous pAge Shopper Locations Address street Cross street Address street Cross street Address street Cross street Address street Cross street 50 348 Johnson Ave Cross Way 68 15905 Orange Blossom Ln Oleander 87 17238 Verdes Robles Winchester Blvd 1 420 Alberto Way Los Gatos Blvd Moving sale featuring furniture, home decor, bathroom Misc. Garage Sale items. Play kitchen, toddler outdoor table, toys, educational Art, bibelot and knickknacks, household items and fixtures, lighting, baby items, children’s books, toys, 69 201 Palmer Dr Wimbledon Dr books, and sporting equipment. some furniture. puzzles, games and more. PlayStation 2, Very Large TV, Clothes, Lamps, Small 88 15244 Via Lomita Monte Sereno 2 420 Alberto Way Hwy 9 – Los Gatos 51 15611 Kavin Ln Daves Ave Bookshelves, TiVo. Quito Rd and Bicknell Rd Saratoga Rd This ain’t no junk...more like lovingly dished up 70 16940 Placer Oaks Rd Los Gatos Boulevard Single home garage sale with costumes, books, scrap- Our 53-unit condominium community is participating junque with style! ...A pine armoire from North Household goods, some kids toys, books, clothing, rugs booking supplies, luggage, clothes and more! There is in the Community Garage Sale. Our vendor’s tables are located on the front lawn. We will have lots of treasures Carolina...Gorgeous high-end baby bedding...A huge 71 16100 Ridgecrest Ave Bancroft Ave something for everyone! Thomas the Tank Wooden Train collection and train 89 including baby and children’s toys and clothing, men Corvette Parts: Wheels and Wheels w/tires, Smoked 168 Villa Ave Main St and Villa Ave and women’s clothing and accessories, kitchenware table...Good stuff...No, we aren’t giving away gold for Glass Top, Engine Programmer, Stock Air Cleaner Assy.