Thatcherism and Women: After Seven Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guardian and Observer Editorial

Monday 01.01.07 Monday The year that changed our lives Swinging with Tony and Cherie Are you a malingerer? Television and radio 12A Shortcuts G2 01.01.07 The world may be coming to an end, but it’s not all bad news . The question First Person Are you really special he news just before Army has opened prospects of a too sick to work? The events that made Christmas that the settlement of a war that has 2006 unforgettable for . end of the world is caused more than 2 million people nigh was not, on the in the north of the country to fl ee. Or — and try to be honest here 4 Carl Carter, who met a surface, an edify- — have you just got “party fl u”? ing way to conclude the year. • Exploitative forms of labour are According to the Institute of Pay- wonderful woman, just Admittedly, we’ve got 5bn years under attack: former camel jockeys roll Professionals, whose mem- before she flew to the before the sun fi rst explodes in the United Arab Emirates are to bers have to calculate employees’ Are the Gibbs watching? . other side of the world and then implodes, sucking the be compensated to the tune of sick pay, December 27 — the fi rst a new year’s kiss for Cherie earth into oblivion, but new year $9m, and Calcutta has banned day back at work after Christmas 7 Karina Kelly, 5,000,002,007 promises to be rickshaw pullers. That just leaves — and January 2 are the top days 16 and pregnant bleak. -

11 — 27 August 2018 See P91—137 — See Children’S Programme Gifford Baillie Thanks to All Our Sponsors and Supporters

FREEDOM. 11 — 27 August 2018 Baillie Gifford Programme Children’s — See p91—137 Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters Funders Benefactors James & Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff & Mary Ball The BEST Trust Binks Trust Lel & Robin Blair Sir Ewan & Lady Brown Lead Sponsor Major Supporter Richard & Catherine Burns Gavin & Kate Gemmell Murray & Carol Grigor Eimear Keenan Richard & Sara Kimberlin Archie McBroom Aitken Professor Alexander & Dr Elizabeth McCall Smith Anne McFarlane Investment managers Ian Rankin & Miranda Harvey Lady Susan Rice Lord Ross Fiona & Ian Russell Major Sponsors The Thomas Family Claire & Mark Urquhart William Zachs & Martin Adam And all those who wish to remain anonymous SINCE Scottish Mortgage Investment Folio Patrons 909 1 Trust PLC Jane & Bernard Nelson Brenda Rennie And all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The AEB Charitable Trust Barcapel Foundation Binks Trust The Booker Prize Foundation Sponsors The Castansa Trust John S Cohen Foundation The Crerar Hotels Trust Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The Ettrick Charitable Trust The Hugh Fraser Foundation The Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund Margaret Murdoch Charitable Trust New Park Educational Trust Russell Trust The Ryvoan Trust The Turtleton Charitable Trust With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by the kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. Media Sponsors We would like to thank the publishers who help to make the Festival possible, Essential Edinburgh for their help with our George Street venues, the Friends and Patrons of the Edinburgh International Book Festival and all the Supporters other individuals who have donated to the Book Festival this year. -

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript Date: Thursday, 24 May 2007 - 12:00AM PRIME MINISTERS IN THE POST-WAR WORLD: ALEC DOUGLAS-HOME D.R. Thorpe After Andrew Bonar Law's funeral in Westminster Abbey in November 1923, Herbert Asquith observed, 'It is fitting that we should have buried the Unknown Prime Minister by the side of the Unknown Soldier'. Asquith owed Bonar Law no posthumous favours, and intended no ironic compliment, but the remark was a serious under-estimate. In post-war politics Alec Douglas-Home is often seen as the Bonar Law of his times, bracketed with his fellow Scot as an interim figure in the history of Downing Street between longer serving Premiers; in Bonar Law's case, Lloyd George and Stanley Baldwin, in Home's, Harold Macmillan and Harold Wilson. Both Law and Home were certainly 'unexpected' Prime Ministers, but both were also 'under-estimated' and they made lasting beneficial changes to the political system, both on a national and a party level. The unexpectedness of their accessions to the top of the greasy pole, and the brevity of their Premierships (they were the two shortest of the 20th century, Bonar Law's one day short of seven months, Alec Douglas-Home's two days short of a year), are not an accurate indication of their respective significance, even if the precise details of their careers were not always accurately recalled, even by their admirers. The Westminster village is often another world to the general public. Stanley Baldwin was once accosted on a train from Chequers to London, at the height of his fame, by a former school friend. -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

Tory Modernisation 2.0 Tory Modernisation

Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg Guy and Shorthouse Ryan by Edited TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 MODERNISATION TORY edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 THE FUTURE OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 The future of the Conservative Party Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a re- trieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Bright Blue is an independent, not-for-profit organisation which cam- paigns for the Conservative Party to implement liberal and progressive policies that draw on Conservative traditions of community, entre- preneurialism, responsibility, liberty and fairness. First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Bright Blue Campaign www.brightblue.org.uk ISBN: 978-1-911128-00-7 Copyright © Bright Blue Campaign, 2013 Printed and bound by DG3 Designed by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Contents Acknowledgements 1 Foreword 2 Rt Hon Francis Maude MP Introduction 5 Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg 1 Last chance saloon 12 The history and future of Tory modernisation Matthew d’Ancona 2 Beyond bare-earth Conservatism 25 The future of the British economy Rt Hon David Willetts MP 3 What’s wrong with the Tory party? 36 And why hasn’t -

Trends in Political Television Fiction in the UK: Themes, Characters and Narratives, 1965-2009

This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Trends in political television fiction in the UK: Themes, characters and narratives, 1965-2009. 1 Introduction British television has a long tradition of broadcasting ‘political fiction’ if this is understood as telling stories about politicians in the form of drama, thrillers and comedies. Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton (1965) is generally considered the first of these productions for a mass audience presented in the then usual format of the single television play. Ever since there has been a regular stream of such TV series and TV-movies, varying in success and audience appeal, including massive hits and considerable failures. Television fiction has thus become one of the arenas of political imagination, together with literature, art and - to a lesser extent -music. Yet, while literature and the arts have regularly been discussed and analyzed as relevant to politics (e.g. Harvie, 1991; Horton and Baumeister, 1996), political television fiction in the UK has only recently become subject to academic scrutiny, leaving many questions as to its meanings and relevance still to be systematically addressed. In this article we present an historical and generic analysis in order to produce a benchmark for this emerging field, and for comparison with other national traditions in political TV-fiction. We first elaborate the question why the study of the subject is important, what is already known about its themes, characters and narratives, and its capacity to evoke particular kinds of political engagement or disengagement. -

Political Islam: a 40 Year Retrospective

religions Article Political Islam: A 40 Year Retrospective Nader Hashemi Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, Denver, CO 80208, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The year 2020 roughly corresponds with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam on the world stage. This topic has generated controversy about its impact on Muslims societies and international affairs more broadly, including how governments should respond to this socio- political phenomenon. This article has modest aims. It seeks to reflect on the broad theme of political Islam four decades after it first captured global headlines by critically examining two separate but interrelated controversies. The first theme is political Islam’s acquisition of state power. Specifically, how have the various experiments of Islamism in power effected the popularity, prestige, and future trajectory of political Islam? Secondly, the theme of political Islam and violence is examined. In this section, I interrogate the claim that mainstream political Islam acts as a “gateway drug” to radical extremism in the form of Al Qaeda or ISIS. This thesis gained popularity in recent years, yet its validity is open to question and should be subjected to further scrutiny and analysis. I examine these questions in this article. Citation: Hashemi, Nader. 2021. Political Islam: A 40 Year Keywords: political Islam; Islamism; Islamic fundamentalism; Middle East; Islamic world; Retrospective. Religions 12: 130. Muslim Brotherhood https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020130 Academic Editor: Jocelyne Cesari Received: 26 January 2021 1. Introduction Accepted: 9 February 2021 Published: 19 February 2021 The year 2020 roughly coincides with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam.1 While this trend in Muslim politics has deeper historical and intellectual roots, it Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral was approximately four decades ago that this subject emerged from seeming obscurity to with regard to jurisdictional claims in capture global attention. -

Intro to the Journalists Register

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 2 October 2018) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £770 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

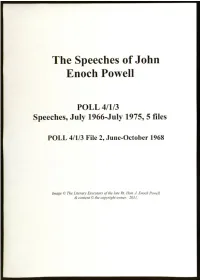

POLL 4/1/3 File 2, June-October 1968

The Speeches of John Enoch Powell POLL 4/1/3 Speeches, July 1966-July 1975, 5 files POLL 4/1/3 File 2, June-October 1968 Image 10 The Literary Executors of the late Rt. Hon. J. Enoch Powell & content c the copyright owner. 2011. 15/6/1968 Government and Nation The Tory Opposition Assoc. of Cons. Clubs AGM Westminster June-Oct 1968 Page 134 18/6/1968 The European Union. Defence Britain's Position In The World Esher Cons. Women’s Advisory June-Oct 1968 Page 125 and Foreign Policy. Committee 21/6/1968 The Economy/Industry Exchange Rate Public Meeting, High Wycombe June-Oct 1968 Page 122 Annual Conference of Conservative 22/6/1968 Education and Literature Education National Advisory Committee on June-Oct 1968 Page 107 Education 28/6/1968 Government and Nation. The Mr Jocelyn Hambro’s Salary West Riding Branch of Institute of June-Oct 1968 Page 102 Economy/Industry. Directors, Harrogate 28-30/06/1968 Government and Nation Conservatism And Social Salary Swinton Conservative College June-Oct 1968 Page 84 10/7/1968 Labour/Socialism/Trade Unions Socialism And Wales Astrid Mynach, Caerphilly June-Oct 1968 Page 82 GLYC Summer School on Defence, 21/7/1968 Defence and Foreign Policy Warsaw Pact June-Oct 1968 Page 76 Oxford 4/9/1968 The Economy/Industry The Fixed Exchange And Dirigisme The Mont Pelerin Society, Aviemore June-Oct 1968 Page 58 Conference 9/9/1968 Defence and Foreign Policy Russia & Nato Rowley Regis Round Table June-Oct 1968 Page 47 12/9/1968 The Economy/Industry Denationalisation Public Meeting, Watford June-Oct 1968 Page 33 18/9/1968 Defence and Foreign Policy Britain's Military Role In The 70S R.U.S.I. -

“They Might Feel Rather Swamped”: Understanding the Roots of Cultural Arguments in Anti-Immigration Rhetoric in 1950S–1980S Britain Author: Chiara Ricci

“They Might Feel Rather Swamped”: Understanding the Roots of Cultural Arguments in Anti-Immigration Rhetoric in 1950s–1980s Britain Author: Chiara Ricci Stable URL: http://www.globalhistories.com/index.php/GHSJ/article/view/53 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2016.53 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Oct. 2016), pp. 33–49 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2016 Chiara Ricci License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. “They Might Feel Rather Swamped”: The Changing in Anti-Immigration Rhetoric in 1950s–1980s Britain CHIARA RICCI Chiara Ricci grew up in Italy and graduated in Pisa with a B.A. with High Honors in Phi- losophy with a major in ethics and civic education. After studying Global Economic History in London School of Economics, she is presently completing her M.A. in Global History at the Free University in Berlin, Germany. She has previously received study grants from the Eras- mus Program to study in Germany and London. Her research interests include 20th century European and international history, international migration history, history of science, and the history of environment. -

Curriculum Vitae of Danny Dorling

January 2021 1993 to 1996: British Academy Fellow, Department of Geography, Newcastle University 1991 to 1993: Joseph Rowntree Foundation Curriculum Vitae Fellow, Many Departments, Newcastle University 1987 to 1991: Part-Time Researcher/Teacher, Danny Dorling Geography Department, Newcastle University Telephone: +44(0)1865 275986 Other Posts [email protected] skype: danny.dorling 2020-2023 Advisory Board Member: ‘The political economies of school exclusion and their consequences’ (ESRC project ES/S015744/1). Current appointment: Halford Mackinder 2020-Assited with the ‘Time to Care’ Oxfam report. Professor of Geography, School of 2020- Judge for data visualisation competition Geography and the Environment, The Nuffield Trust, the British Medical Journal, the University of Oxford, South Parks Road, British Medical Association and NHS Digital. Oxford, OX1 3QY 2019- Judge for the annual Royal Geographical th school 6 form essay competition. 2019 – UNDP (United Nations Development Other Appointments Programme) Human Development Report reviewer. 2019 – Advisory Broad member: Sheffield Visiting Professor, Department of Sociology, University Nuffield project on an Atlas of Inequality. Goldsmiths, University of London, 2013-2016. 2019 – Advisory board member - Glasgow Centre for Population Health project on US mortality. Visiting Professor, School of Social and 2019- Editorial Board Member – Bristol University Community Medicine, University of Bristol, UK Press, Studies in Social Harm Book Series. 2018 – Member of the Bolton Station Community Adjunct Professor in the Department of Development Partnership. Geography, University of Canterbury, NZ 2018-2022 Director of the Graduate School, School of Geography and the Environment, Oxford. 2018 – Member of the USS review working group of the Council of the University of Oxford. -

Clarke, Amy.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details National Lives, Local Voices Boundaries, hierarchies and possibilities of belonging Amy Clarke Department of Geography, University of Sussex Thesis submitted to the University of Sussex for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 2 Work not Submitted Elsewhere for Examination I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature…………………………………………. 3 Contents Contents 3 Acknowledgements 6 Abstract 7 List of figures 8 Map of the research area 9 1. Introduction 10 1.1 Research aims 11 1.2 Outline of the thesis 13 2. Britain and ‘Britishness’: belonging, nation and identity 17 2.1 From multiculturalism to British values 18 2.2 National belonging, boundaries and hierarchies 21 2.3 The (white) middle-classes in England 25 2.4 Whiteness and (post)colonial continuities 30 2.5 National identification in England 35 2.6 British attitudes to immigration 39 2.7 Asking questions 44 2.8 Conclusion 46 3.