WHO IS RUTO? the Handshakes and the Fear It Is Spreading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

National Assembly

October 5, 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Wednesday, 5th October, 2016 The House met at 9.30 a.m. [The Deputy Speaker (Hon. (Dr.) Laboso) in the Chair] PRAYERS QUORUM Hon. Deputy Speaker: Can we have the Quorum Bell rung? (The Quorum Bell was rung) Hon. Deputy Speaker: Okay Members. Let us settle down. We are now ready to start. We have a Petition by Hon. Njuki. POINT OF ORDER PETITION ON ALLEGED MISAPPROPRIATION OF FUNDS BY THE KENYA SWIMMING FEDERATION Hon. Njuki: Thank you, Hon. Deputy Speaker for giving me the opportunity this morning to air my sentiment on the issue of petitions. According to Standing Order No.227 on the committal of petitions, a petition is supposed to take, at least, 60 days to be dealt with by a Committee. Hon. Deputy Speaker: Hon. Njuki, I am just wondering whether whatever you are raising was approved or not. Hon. Njuki: Hon. Deputy Speaker, I do not have a petition. I just have a concern about a petition I brought to this House on 12th November, 2015. It touches on a very serious issue. It is a petition on the alleged mismanagement and misappropriation of funds by the Kenya Swimming Federation. That was in November 2015. This Petition has not been looked into. Considering what happened during the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, there were complaints about the Federation taking people who were not qualified to be in the swimming team. To date nothing has happened. I know the Committee is very busy and I do not deny that, but taking a whole year to look at a petition when the Standing Orders say it should be looked into in 60 days is not right. -

Newspaper Visibility of Members of Parliament in Kenya*

Journalism and Mass Communication, ISSN 2160-6579 D July 2012, Vol. 2, No. 7, 717-734 DAVID PUBLISHING Newspaper Visibility of Members of Parliament in Kenya* Kioko Ireri Indiana University, Bloomington, USA This research investigates variables that predicted news coverage of 212 members of parliament (MPs) in Kenya by four national newspapers in 2009. The 10 variables examined are: ordinary MP, cabinet minister, powerful ministry, parliamentary committee chairmanship, seniority, big tribe identity, major party affiliation, presidential ambition, commenting on contentious issues, and criticizing government. Findings indicate that commenting on contentious issues, criticizing government, cabinet minister, ordinary MP, powerful ministry, and seniority significantly predicted visibility of the parliamentarians in newspaper news. However, a multiple regression analysis shows that the strongest predictors are commenting on contentious issues, cabinet minister, criticizing government, and big tribe identity. While commenting on controversial issues was the strongest predictor, major party identification and committee leadership were found not to predict MPs’ visibility. Keywords: Kenya, members of parliament (MPs), newspapers, newspaper visibility, politicians, visibility, visibility predictor Introduction Today, the mass media have become important platforms for the interaction of elected representatives and constituents. Through the mass media, citizens learn what their leaders are doing for them and the nation. Similarly, politicians use the media to make their agendas known to people. It is, thus, rare to come across elected leaders ignorant about the importance of registering their views, thoughts, or activities in the news media. In Kenya, members of parliament have not hesitated to exploit the power of the mass media to its fullest in their re-election bids and in other agendas beneficial to them. -

National Constitutional Conference Documents

NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCE DOCUMENTS THE REPORT OF THE RAPPORTEUR GENERAL TO THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCE ON ITS DELIBERATIONS BETWEEN AUGUST 18 – SEPTEMBER 26, 2003 AT THE BOMAS OF KENYA 17TH NOVEMBER, 2003 OUTLINE OF CONTENTS 1. Interruptions in Mortis Causae 2. The Scope of the Report 3. Issues Outstanding at the end of Bomas I 3.1 On devolution of powers 3.2 On Cultural Heritage 3.3 On affirmative action 4. Deliberations of Technical Working Committees 4.1 The Constitution of Technical Working Committees 4.2 The Operation of Technical Working Committees 5. The Roadmap to Bomas III Appendices A. National Constitutional Conference Process B. Membership of Technical Working Committees of the National Constitutional Conference C. Cross-cutting issues with transitional and consequential implications D. List of Individuals or Institutions providing input to Technical Working Committees during Bomas II E. Detailed process in Technical Working Committees F. Template for Interim and final Reports of Committees G. Template for Committee Reports to Steering Committee and Plenary of the Conference 1 THE REPORT OF THE RAPPORTEUR-GENERAL TO THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCE ON ITS DELIBERATIONS BETWEEN AUGUST 18 – SEPTEMBER 26, 2003 AT THE BOMAS OF KENYA 1. Interruptions in mortis causae 1. Twice during Bomas II, thel Conference was stunned by the sudden and untimely demise of two distinguished delegates, namely: - ° Delegate No.002, the late Hon. Kijana Michael Christopher Wamalwa, MP, Vice-President and Minister for Regional Development, and ° Delegate No. 412,the late Hon. Dr. Chrispine Odhiambo Mbai, Convenor of the Technical Working Committee G on Devolution. 2. Following the demise of the Vice-President in a London Hospital on August 25, 2003, H. -

Devolution Conference 23Rd - 27Th April 2018 Kakamega High School Kakamega County

THE FIFTH ANNUAL DEVOLUTION CONFERENCE 23RD - 27TH APRIL 2018 KAKAMEGA HIGH SCHOOL KAKAMEGA COUNTY “Sustainable, Productive, Effective and Efficient Governments for Results Delivery” Our Vision Prosperous and democratic Counties delivering services to every Kenyan. Our Mission To be a global benchmark of excellence in devolution that is non-partisan; providing a supporting pillar for County Government as a platform for consultation, information sharing, capacity building, performance management and dispute resolution. Our Values Our core values are: professionalism, independence, equality and equity, cooperation and being visionary. Our Motto 48 Governments, 1 Nation. THE FIFTH ANNUAL DEVOLUTION CONFERENCE 2018 | i A publication by: The Council of County Governors (COG) Delta Corner, 2nd Floor, Opp PWC Chiromo Road, Off Waiyaki Way P.O Box 40401 - 00100 Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] Phone: +254 (020) 2403313/4 Mobile: +254729777281 http://www.cog.go.ke ©November 2018 The production of this report was supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Agile and Harmonized Assistance for Devolved Institutions (AHADI) Program. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents Abbreviations v Foreword vii Statement By The Chairperson, Devolution Conference Steering Committee viii Acknowledgement ix Executive Summary xi 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Conference Objectives 1 1.3 Opening Ceremony 2 -

Changing Kenya's Literary Landscape

CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE Part 2: Past, Present & Future A research paper by Alex Nderitu (www.AlexanderNderitu.com) 09/07/2014 Nairobi, Kenya 1 CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE Contents: 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 2. Writers in Politics ........................................................................................................ 6 3. A Brief Look at Swahili Literature ....................................................................... 70 - A Taste of Culture - Origins of Kiswahili Lit - Modern Times - The Case for Kiswahili as Africa’s Lingua Franca - Africa the Beautiful 4. JEREMIAH’S WATERS: Why Are So Many Writers Drunkards? ................ 89 5. On Writing ................................................................................................................... 97 - The Greats - The Plot Thickens - Crime & Punishment - Kenyan Scribes 6. Scribbling Rivalry: Writing Families ............................................................... 122 7. Crazy Like a Fox: Humour Writing ................................................................... 128 8. HIGHER LEARNING: Do Universities Kill by Degrees? .............................. 154 - The River Between - Killing Creativity/Entreprenuership - The Importance of Education - Knife to a Gunfight - The Storytelling Gift - The Colour Purple - The Importance of Editors - The Kids are Alright - Kidneys for the King -

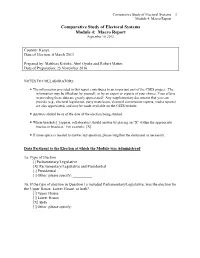

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Kenya Date of Election: 4 March 2013 Prepared by: Matthias Krönke, Abel Oyuke and Robert Mattes Date of Preparation: 23 November 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [] Parliamentary/Legislative [X] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [X] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Party of National Unity and Allies (National Rainbow Coalition) 2b. -

Parliament of Kenya the Senate

November 3, 2015 SENATEDEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Tuesday, 3rd November, 2015 The Senate met at the Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, at 2.30 p.m. [The Deputy Speaker (Sen. Kembi-Gitura) in the Chair] PAPERS LAID Sen. Billow: Mr. Deputy Speaker, Sir, I beg to lay the following Papers on the Table of the Senate today, Tuesday, 3rd November, 2015:- THE REPORT ON THE PETITION ON ALLEGED FLAWS IN THE BUSIA COUNTY BUDGET MAKING PROCESS The Report of the Standing Committee on Finance, Commerce and Budget on the examination of the Petition by Hon. Vincent Wanyama Opisa, MCA, on alleged flaws in the Busia County budget making process. REPORT ON CRA CIRCULAR ON FINANCING OF NON-CORE CAPITAL PROJECTS Report on the Standing Committee on Finance, Commerce and Budget on the Message from the County Assembly of Kilifi on Commission of Revenue Allocation Circular No.5/2015 dated 19th May, 2015 on financing of non-core capital projects. REPORT ON THE PETITION BY MAJOR (RTD.) JOEL KIPRONO ROP ON THE STATE OF KENYA’S ECONOMY Report of the Standing Committee on Finance, Commerce and Budget on the examination of the Petition by Major (Rtd.) Joel Kiprono Rop, a resident of Bomet County on the state of Kenya’s economy. (Sen. Billow laid the documents on the Table) Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Senate Hansard Report is for information purposes only. A certified version of this Report can be obtained from the Hansard Editor, Senate. November 3, 2015 SENATEDEBATES 2 STATEMENTS The Deputy Speaker (Sen. -

Transparency in Kenya's Upstream Oil and Gas Sector

Beating the Resource Curse: Transparency in Kenya’s Upstream Oil and Gas Sector by Sally Lesley Brunton Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Political Science in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Ian Taylor March 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University. All rights reserved. i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract In 2012 Tullow Oil plc discovered commercial quantities of crude oil onshore Kenya. Additional commercial discoveries have subsequently been made and estimates suggest that Kenya’s oil reserves are substantial. Steps towards the development and production of these reserves are progressing and Kenya is thus preparing to become another of sub-Saharan Africa’s oil-exporting states. Nevertheless, experience has shown that the majority of these resource-rich states have succumbed to symptoms of the ‘resource curse’: economic and human development and growth has been hindered rather than helped and many of these states find themselves struggling to escape from the clutches of rent-seeking, bribery and corruption. In an attempt to determine how best Kenya might avoid the negative impacts of the curse this study examines various strands of resource curse theory. -

Exiting University Administration

16 Exiting University Administration My tenure as a Vice-Chancellor was eventful, rich and fulfilling. The ascent from a deputy principal to the rank of a university leader had its consequences. My interaction with all types of individuals within and without the university precincts taught me various lessons and hardened my resolve and approach to issues. The sudden news of my appointment to JKUAT, which is discussed elsewhere, took the same mode on departure. I was taught one thing by my father when I was growing up. He always said that as one grows up, one expects the very best in life. The key word here is “expects”. He would then remark, “Young boy, life ahead is full of challenges and big responsibilities.” I literally witnessed and experienced the same. The 2002 Kenyan General Election Kenyan politics are unpredictable. I grew up hearing of the Founding Father of Kenya, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta. He was the first Chancellor of the University of Nairobi. His two Vice-Chancellors were Dr Josephat Karanja, who became the vice-president of Daniel Arap Moi and Prof. Joseph Maina Mungai, who served under both presidents. Graduation ceremonies at the university of Nairobi were pompous, colourful and unifying. It was the only university then and it was mandatory that the Chancellor personally presides over the ceremony. I worked under President Moi for virtually all the period I was a Vice- Chancellor. Vice-Chancellors in Kenya’s five public universities were appointees of the president. These positions were therefore political in nature. The individual university acts specified so. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.)

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXI—No. 17 NAIROBI, 8th February, 2019 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 1202 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 1204 THE COMPANIES ACT THE STATE CORPORATIONS ACT (Cap. 486) (Cap. 446) THE JOMO KENYATTA FOUNDATION THE KENYA NUCLEAR ELECTRICITY BOARD ORDER, 2012 APPOINTMENT APPOINTMENT IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by paragraph 26 of the IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 7 (1) (a) of the Memorandum and Articles of Association of the Jomo Kenyatta Kenya Nuclear Electricity Board Order, 2012, I, Uhuru Kenyatta, Foundation, I, Uhuru Kenyatta, President and Commander-in-Chief of President and Commander-in-Chief of the Kenya Defence Forces the Kenya Defence Forces, appoint— appoint— KHADIJA M. AWALE EZRA ODONDI ODHIAMBO to be the Chairperson of the Board of the Jomo Kenyatta Foundation, to be an Executive Chairman of the Kenya Nuclear Electricity Board, for a period of three (3) years, with effect from the 8th February, 2019. for a period of three (3) years, with effect from the 8th February, 2019. Dated the 8th February 2019. Dated 8th February, 2019. UHURU KENYATTA, UHURU KENYATTA, President. President. GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 1203 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 1205 THE KENYA MARITIME AUTHORITY ACT THE ENERGY ACT (No. 5 of 2006) (No. 12 of 2006) APPOINTMENT THE RURAL ELECTRIFICATION AUTHORITY IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 6 (a) of the RE-APPOINTMENT Kenya Maritime Authority Act, 2006, I, Uhuru Kenyatta, President of the Republic of Kenya and Commander-in-Chief of the Defence IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 68 (1) (a) of the Forces, appoint— Energy Act, I, Uhuru Kenyatta, President and Commander-in-Chief of the Kenya Defence Forces re-appoint— GEOFFREY NGOMBO MWANGO SIMON N. -

Newsletter | May 2016 | UNDP Intensifies Wildlife Conservation Efforts in Africa

Newsletter | May 2016 | UNDP Intensifies Wildlife Conservation Efforts in Africa UNON Director-General, Sahle-Work Zewde flagging off UN Team for Inter- agency Games hosted in Spain on 11-15 May 2016. UNDP and the GEF investing $60m into Africa is intended to help create incentives for conservation and ensure better management of wildlife protected areas. The Government of Kenya, led by President Uhuru Kenyatta burnt 105 tonnes of ivory and 1.3 tonnes of rhino horns to make a statement that the world must stop the trade in wildlife trophies in order to protect its threatened heritage. “Wildlife poaching and the illicit (Photo by UNDP) trade of wildlife and forest products are abhorrent,” said UNDP Administrator NDP has reiterated its wildlife through a new Global Wildlife Helen Clark at the Space for Giants forum, renewed support to frontline Programme being initiated with funding a high-level conservation event in Kenya. Uconservation efforts to from the Global Environmental Facility “This multi-billion dollar worldwide trade help African countries protect their (GEF). The programme, which will see is a security issue, an environmental issue, CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 Goal 17 - Page 9 What’s Inside: Upcoming Events: UNDP Intensifies Wildlife Conservation Efforts in Africa 4 June International Day of Innocent Children Victims of Aggression President Uhuru Kenyatta on Official Visit to UNESCO 5 June World Environment Day Impact Investment Showcase in Kenya highlights social 8 June World Oceans Day enterprise supporting SDGs 12 June World Day Against Child Labour Raising awareness on climate change step by step 16 June Day of the African Child UN-Habitat last month hosted and honored the first 17 June World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought cohort of Emerging Community Champions.