3 Nutrition in Cardiac Rehabilitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Diet As Tolerated/Diet of Choice This Is for Communication Only

SVMC INTERPRETATION OF DIET ORDERS SVMC menu plans are developed using best evidenced based practice guidelines. The Clinical Diet Manual is the basis for our menu planning and patient education materials. Listed below is a brief summary of the menu plans provided by SVMC and any specifics that may differ from the Clinical Diet Manual. Our regular non select menu serves as the basis for all our menu plans and follows the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI’s/RDA’s) for our population of male 51-70 years old. Menus are designed to meet nutritional requirements specified by the 2011 update of the DRI’s from the Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academies of Science’s guidelines. This menu is then further modified to meet the specific needs of each patient based on diet order, nutritional status, food allergies, age, cultural preferences and food likes and dislikes. Current Dietary Reference Intakes recommend that Sodium intake remain less than 2300 mg per day. In order to meet their preferences and maintain intake, most diets that do not indicate a Sodium restriction will exceed this value. A sodium restriction should be ordered if needed. Due to limitations within our nutrient database (CBORD) we do not have values available to us for all nutrients. Currently our database is incomplete for: biotin, choline, chromium, molybdenum, fluoride, iodine, chloride, linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid and sometimes other micronutrients. Thin liquids are a default for all diets. Nectar, honey, pudding fluid consistency or fluid restriction needs to be ordered under “DIET CATEGORY”. If oral nutrition supplements (ONS) are ordered BID with meals, i.e. -

CARDIAC DIET: How to Place an Order Your Physician Has Ordered a Cardiac Diet for You

Breakfast Entrees (please Choice 7) BREAKFAST Eggs: Scrambled - Egg Whites - Hard–Boiled eggs (2) Beverages Omelet: Egg - Egg White Coffee:Regular - Decaffeinated Choice of 4 Toppings: Red Onions - Broccoli - Spinach Tea: Regular - Decaffeinated - Chamomile Fresh Brewed Ice Tea Peppers - Mushroom - Turkey - Swiss Cheese Hot Chocolate: Sugar-Free Pancakes: Buttermilk - Blueberry - Banana Milk: Skim - Lactaid - Vanilla Soy French Toast: Plain - Blueberry - Banana Low Fat Chocolate Soda: Ginger-Ale - Diet Ginger - Ale - Seltzer Healthy Sandwich Option: Juice: Orange - Apple - Cranberry - Prune - V8 Egg Whites Condiments Fresh Turkey & Lacy Swiss on Whole Wheat Kaiser Roll Smart Balance - Grape Jelly –Strawberry Jelly - Diet Jelly - Lite Cream Cheese - Lemon Juice - Coffee Creamer - Syrup - pepper Breakfast Bakery-(please choose 1 item only) Herb Seasoning - Peanut Butter - Ketchup - Honey Muffins:Blueberry - Corn - Bran Honey Mustard - BBQ Sauce - Lite Mayo - Salsa Bagels: Plain - Sesame - Everything - Whole Wheat - Kaiser Roll Fruit Whole Fruit: Banana - Orange - Apple - Grapes Chilled Fruit: Peaches - Pears - Applesauce Mandarin Oranges - Fruit Salad - Seasonal Melon Yogurt Lite: Strawberry - Peach - Vanilla - Plain Cereal Hot: Oatmeal - Cinnamon Oatmeal - Cream of Wheat Cold: Corn Flakes - Cheerios - Rice Krispies Raisin Bran - Rice Chex *Breakfast Ends Daily at 10:00AM* Limited Items are available all day long. Scrambled Eggs, Omelets, Cereal and Bagels 1 LUNCH & DINNER ‘Shake It Up’ Salad Station Choice of (1)Lettuce: Romaine - Baby -

Mechanical Soft Cardiac Diet: Lunch: 11 AM - 1 PM This Diet Is Beneficial for the Treatment and Dinner: 4 - 5 PM Prevention of Heart Disease

Ordering About Your Diet Breakfast: 7 - 9 AM Mechanical Soft Cardiac Diet: Lunch: 11 AM - 1 PM This diet is beneficial for the treatment and Dinner: 4 - 5 PM prevention of heart disease. The diet is low fat, low cholesterol, low sodium and limits caffeine. When ordering, please dial extension 6255. After Fried, fatty and salty foods such as ham, bacon, placing your order, you can expect your meal to sausage, cream sauces, whole milk, whole milk arrive within 45 minutes. Please remember, the cheeses, salt and caffeinated beverages are nursing staff is available to assist you with menu limited. All ground meat will have either gravy or selections during your stay. sauce to keep it moist to ease the chewing and swallowing. Guest Meals Your 100% satisfaction is our number one goal. Lucas County Health Center offers guest meals for If, for any reason, our meal service does not meet Mechanical delivery to the patient rooms. Guests may order your expectations, please items from the patient menu at the following cost: call the Dietary Manager at Soft Cardiac extension 3206 and let us Breakfast: $3 Lunch: $5 Dinner: $5 know how we can better Diet serve you, our guest. Room Service Menu Each meal includes one entree selection (excluding breakfast) and the side dishes and/or dessert you would like to enjoy with your meal. When deciding what to have for your meal, The envelope with the price of the meal will be please make one placed on your guest tray for payment. entree selection from the Lunch & When ordering, please dial extension 3244. -

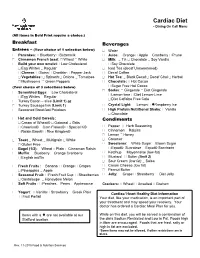

Cardiac Diet Menu

Cardiac Diet - Dining On Call Menu (All items in Bold Print require a choice.) Breakfast Beverages Entrées – (Your choice of 1 selection below) Water Pancakes: Blueberry Buttermilk Juice: Orange Apple Cranberry Prune Cinnamon French toast: Wheat White Milk: 1% Chocolate Soy Vanilla Build your own omelet Low Cholesterol Soy Chocolate Egg Whites Regular Iced Tea (decaf Unsweetened) Cheese: Swiss Cheddar Pepper Jack Decaf Coffee Vegetables: Spinach Onions Tomatoes Hot Tea: Black Decaf Decaf Chai Herbal Mushrooms Green Peppers Chocolate: Hot Cocoa (Your choice of 3 selections below) Sugar Free Hot Cocoa Sodas: Gingerale Diet Gingerale Scrambled Eggs: Low Cholesterol Lemon-lime Diet Lemon-Lime Egg Whites Regular Diet Caffeine Free Cola Turkey Bacon – slice (Limit 1) or Turkey Sausage link (Limit 1) Crystal Light: Lemon ♦Raspberry Ice Seasoned Breakfast Potatoes High Protein Nutritional Shake: Vanilla Chocolate Hot and Cold Cereals: Condiments Cream of Wheat® Oatmeal Grits Cheerios® Corn Flakes® Special K® Pepper Herb Seasoning Raisin Bran® Rice Krispies® Cinnamon Raisins Lemon Honey Toast Wheat Multigrain White Creamer Gluten Free Sweetener: White Sugar Brown Sugar Bagel (1/2): Wheat Plain Cinnamon Raisin Equal® Sucralose Equal® Saccharin Muffin: Blueberry Orange Cranberry Ketchup Mayonnaise (low-fat) English muffin Mustard Butter (limit 2) Sour Cream (low fat) Salsa Fresh Fruits : Banana Orange Grapes Cream Cheese (low fat) Pineapples Apple Peanut Butter Seasonal Fruit: Fresh Fruit Cup Strawberries Jelly: Grape Strawberry Diet Jelly Cantaloupe Honeydew Melon Soft Fruits : Peaches Pears Applesauce Crackers: Wheat Unsalted Graham Yogurt: Vanilla Strawberry Greek Plain Cardiac/ Heart Healthy Diet Information Fruit Parfait Your diet, like your medication, is an important part of your treatment and may speed your recovery. -

+2000 Niche Topics

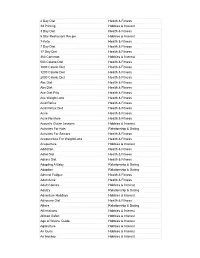

2 Day Diet Health & Fitness 3d Printing Hobbies & Interest 3 Day Diet Health & Fitness 5 Star Restaurant Recipe Hobbies & Interest 7-Keto Health & Fitness 7 Day Diet Health & Fitness 17 Day Diet Health & Fitness 360 Cameras Hobbies & Interest 500 Calorie Diet Health & Fitness 1000 Calorie Diet Health & Fitness 1200 Calorie Diet Health & Fitness 2000 Calorie Diet Health & Fitness Abc Diet Health & Fitness Abs Diet Health & Fitness Ace Diet Pills Health & Fitness Ace Weight Loss Health & Fitness Acid Reflux Health & Fitness Acid Reflux Diet Health & Fitness Acne Health & Fitness Acne No More Health & Fitness Acoustic Guitar Lessons Hobbies & Interest Activities For Kids Relationship & Dating Activities For Seniors Health & Fitness Acupuncture For Weight Loss Health & Fitness Acupunture Hobbies & Interest Addiction Health & Fitness Adhd Diet Health & Fitness Adkins Diet Health & Fitness Adopting A Baby Relationship & Dating Adoption Relationship & Dating Adrenal Fatigue Health & Fitness Adult Acne Health & Fitness Adult Comics Hobbies & Interest Adultry Relationship & Dating Adventure Holidays Hobbies & Interest Advocare Diet Health & Fitness Affairs Relationship & Dating Affirmations Hobbies & Interest African Safari Hobbies & Interest Age of Wushu Guide Hobbies & Interest Agriculture Hobbies & Interest Air Guns Hobbies & Interest Air Hockey Hobbies & Interest Airbrush Hobbies & Interest Akido Hobbies & Interest Alcohol Addiction Health & Fitness Alkaline Diet Health & Fitness Allergies Health & Fitness Allergy Health & Fitness Altered Books -

Saunders 2014-2015 Strategies for Test Success

Quick Reference Guide to Strategies Alternate Item Formats, p. 30 Avoiding “Reading into the Question”, p. 42 Ingredients of the Question, p. 42 Strategic Words or Phrases, p. 46 The Subject of the Question, p. 47 Nursing Knowledge and the Process of Elimination, p. 48 Positive and Negative Event Queries, p. 52 Prioritization, p. 61 Strategic Words or Phrases, p. 64 The ABCs–Airway, Breathing, Circulation, p. 66 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory, p. 67 The Steps of the Nursing Process (Clinical Problem-Solving Process), p. 70 Delegating and Assignment Making, p. 77 Time Management, p. 85 Communication, p. 87 Cultural Considerations, p. 90 Pharmacology, p. 100 Medications and Intravenous Calculations, p. 111 Closed-ended Words, p. 113 Medical vs. Nursing Interventions, p. 115 Comparable or Alike Options, p. 116 Parts of an Option, p. 117 Umbrella Option, p. 117 Laboratory Values, p. 118 Visualizing the Information, p. 121 Client Positioning, p. 122 Therapeutic Diets, p. 124 Disasters, p. 129 SAUNDERS 2014–2015 for PASSING NURSING SCHOOL and the NCLEX® EXAM Even More Questions on ! http://evolve.elsevier.com/Silvestri/strategies/ Evolve Access Code: How to Use the Online Practice Questions Customize your study session for your time and your own unique needs Study Mode Receive immediate feedback after each question Select questions by Strategy, Client Needs, Integrated Process, Alternate Item Format Type, or specific Content Area. The answer, rationale, test-taking strategy, question codes, and reference source(s) for further remediation appear immedi- ately after you answer each question. Exam Mode Take a practice exam, and receive your results and feedback at the end Select questions by Strategy, Client Needs, Integrated Process, Alternate Item Format Type, or specific Content Area. -

Supplementary Information

1073 Supplementary Information Glossary – 1074 Index – 1077 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 D. Noland et al. (eds.), Integrative and Functional Medical Nutrition Therapy, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30730-1 1074 Glossary Glossary AMI Any mental illness – a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder EPA Eicosapentaenoic acid – 22 C; N-3 fatty acid; plays a role in mem- (excluding developmental and substance use disorders) brane function; Can be synthesized from alpha linolenic acid (ALA), although not efficiently (<5%) Behavioral health nutrition An umbrella term incorporating condi- tions with altered, mental, and intellectual states that may be influ- Epigenetics Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene enced by nutrients or nutritional status. expression (active versus inactive genes) that does not involve changes to the underlying DNA sequence – a change in phenotype without a BDNF gene The BDNF gene provides instructions for making a protein change in genotype – which, in turn, affects how cells read the genes. found in the brain and spinal cord called brain-derived neurotrophic Epigenetics affects how genes are read by cells and subsequently how factor. This protein promotes the survival of nerve cells (neurons) by they produce proteins [5]. Epigenetics is the reason why a skin cell playing a role in the growth, maturation (differentiation), and main- looks different from a brain cell or a muscle cell. All three cells contain tenance of these cells. In the brain, the BDNF protein is active at the the same DNA, but their genes are expressed differently (turned “on” or connections between nerve cells (synapses), where cell-to-cell com- “off”), which creates the different cell types [4]. -

Deborah J. Clegg

Deborah J. Clegg Curriculum Vitae Education: 1986 BS, Nutrition, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 1993 MBA, Boston University, Boston, MA 2000 PhD, Nutrition, University of Georgia, Athens, GA (Advisor: Roy Martin) 2000-2002 Post-Doctoral Fellow, Obesity Research Center, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (Advisor: Steve Woods) Licensure: 1987-Present Registered Dietitian, American Dietetic Association 1993-2000 Georgia State Licensed Dietitian 2000-2009 Ohio State Licensed Dietitian Board Certification: 1990-1995 Board Certified, Diabetes Education (CDE) Professional Experience: 1994-1997 Instructor, Department of Nutrition, Emory University 2002-2008 Assistant Professor (Tenure Track), Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati 2008-2011 Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center with a joint appointment in the Department of Clinical Nutrition 2011-2014 Associate Professor with Tenure, Dept of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center with a joint appointment in the Department of Clinical Nutrition 2013-2014 Chair, Department of Clinical Nutrition 2014-2018 Professor, Departments of Internal Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Research Scientist III, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center 2018-2019 Visiting Professor, Departments of Internal Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Research Scientist III, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center 2014-2018 Professor, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) 2018-2019 Visiting Professor-in-Residence, University -

Advanced Diet As Tolerated/Diet of Choice This Is for Communication Only

SVMC INTERPRETATION OF DIET ORDERS SVMC menu plans are developed using best evidenced based practice guidelines. The Clinical Diet Manual is the basis for our menu planning and patient education materials. Listed below is a brief summary of the menu plans provided by SVMC and any specifics that may differ from the Clinical Diet Manual. Our regular menu serves as the basis for all our menu plans and follows the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI’s/RDA’s) for our population of male 51-70 years old. Menus are designed to meet nutritional requirements specified by the 2011 update of the DRI’s from the Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academies of Science’s guidelines. This menu is then further modified to meet the specific needs of each patient based on diet order, nutritional status, food allergies, age, cultural preferences and food likes and dislikes. Current Dietary Reference Intakes recommend that Sodium intake remain less than 2300 mg per day. In order to meet their preferences and maintain intake, most diets that do not indicate a Sodium restriction will exceed this value. A sodium restriction should be ordered if needed. Due to limitations within our nutrient database (CBORD) we do not have values available to us for all nutrients. Currently our database is incomplete for: biotin, choline, chromium, molybdenum, fluoride, iodine, chloride, linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid and sometimes other micronutrients. Thin liquids are a default for all diets. Nectar, honey, pudding fluid consistency or fluid restriction needs to be ordered. When oral supplements are ordered BID with meals, i.e. -

Improving the Health of the Public by 2040

Improving the health of the public by 2040 Optimising the research environment for a healthier, fairer future September 2016 The Academy of Medical Sciences is most grateful to Professor Dame Anne Johnson DBE FMedSci and other members of the working group for their contributions and commitment to this project. We thank the Academy’s Council members, the external review group, the Academy’s staff, workshop attendees, public dialogue participants and all other individuals who contributed to the report. This report is published by the Academy and has been endorsed by its Officers and Council. Contributions by the working group were made purely in an advisory capacity. Working group members participated as individuals and not as representatives of their affiliated universities, organisations or associations. All web references were accessed in July 2016. This work is © The Academy of Medical Sciences and is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Improving the health of the public by 2040 Contents Executive summary ..................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 7 1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................11 2. A healthier, fairer future ........................................................................................ 25 3. Optimising research to improve the -

The Cardiac Diet Explained Diet the Cardiac by Julie Nyhus, FNP-BC UDRA11 / SHUTTERSTOCK / UDRA11

heart matters 11/22/2019 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3d0gbN0a5/T9JmmD8ac1jAYPDFWV8bEl4jjo2RC/9XaU= by https://journals.lww.com/nursingmadeincrediblyeasy from Downloaded The cardiac diet explained By Julie Nyhus, FNP-BC Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/nursingmadeincrediblyeasy Managing cardiovascular disease (CVD) fish, whole grains and cereals, and moder- often involves a combination of pharma- ate amounts of red wine and dairy. The cologic therapy and a solid dietary ap- gaps that exist within the Mediterranean proach known as the “cardiac diet.” It’s diet regarding positive outcomes on heart critical that the foods we recommend for health are limited to the recommendations our patients be as carefully planned as of wine and dairy in moderation and the by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3d0gbN0a5/T9JmmD8ac1jAYPDFWV8bEl4jjo2RC/9XaU= the pharmacologic care they receive be- inclusion of whole grains and cereals. cause diet is an important part of cardiac The Lyon Diet Heart Study showed a health. Although there are often nutrition remarkable 72% decrease over a nearly controversies in scientific journals and 5-year period in major cardiovascular events among the lay press, there are evidence- for those who consumed a Mediterranean- based and broadly recognized recom- type diet compared with control groups. mendations that you can consider when This randomized controlled trial validated caring for patients with CVD, whether that diet plays a significant role in the sec- inpatient or outpatient. This article re- ondary prevention of CVD, and numerous views the top evidence-based cardiac diet prospective studies have also confirmed recommendations and discusses interven- these findings. The Lifestyle Heart Trial, a tions for nurses who assess, educate, and randomized controlled study that included care for patients with CVD. -

Transcripts Of: ALAN WATT

Transcripts of: ALAN WATT "CUTTING THROUGH THE MATRIX" LIVE ON RBN #76 - 100 February 15, 2008 - April 11, 2008 Dialogue Copyrighted Alan Watt - 2008 (Exempting Music, Literary Quotes and Callers' Comments) Alan Watt's Official Websites: WWW.CUTTINGTHROUGHTHEMATRIX.COM www.alanwattsentientsentinel.eu "Parting with Privacy and "Look Out This Year, They're Going High Gear the New Social Paradigm" - Feb. 15, 2008 - Prices will Rise, Bringing Disorder, Then Troops will Cross the Border" - March 17, 2008 "Governance by Conology and Coercive Perception Validation" - Feb. 18, 2008 "Bring on the Clown as We All Go Down" - March 19, 2008 "Helmets for Hell-Mutts - No Pain Game for Interfacing Your Brain" - Feb. 20, 2008 "One King's Utopia is a Peasantry's Hell - It's All a Matter of Perception" - "Tattooed Telephone for Compulsive Tattlers - March 21, 2008 Touch-Skin Programming for Programmable People" - Feb. 22, 2008 "Major Moves on Minors - Government Wants Predictability for Totalitarian Society" - "Weather Warfare or Climate Change - March 24, 2008 Watt's the Answer?" - Feb. 25, 2008 "Zimbardo Experimented to Drive Men "Pupils Properly Parroting Predictive Demented - Stanford University Psychological Programming - Well, What Else?" - Department's Involvement in Role Playing Feb. 27, 2008 Predictability for Master-Slave Situations" - March 26, 2008 "Planning for Planetary Interrogation - Cradle to Grave for Perfect Slave" - "The Application of Apathy and Learned Feb. 29, 2008 Helplessness for Guiding Society through a Post-Consumerist, Trans-