The Role of Identity in India's Expanding Naval Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India in the Indian Ocean Donald L

Naval War College Review Volume 59 Article 6 Number 2 Spring 2006 India in the Indian Ocean Donald L. Berlin Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Berlin, Donald L. (2006) "India in the Indian Ocean," Naval War College Review: Vol. 59 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol59/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen Berlin: India in the Indian Ocean INDIA IN THE INDIAN OCEAN Donald L. Berlin ne of the key milestones in world history has been the rise to prominence Oof new and influential states in world affairs. The recent trajectories of China and India suggest strongly that these states will play a more powerful role in the world in the coming decades.1 One recent analysis, for example, judges that “the likely emergence of China and India ...asnewglobal players—similar to the advent of a united Germany in the 19th century and a powerful United States in the early 20th century—will transform the geopolitical landscape, with impacts potentially as dramatic as those in the two previous centuries.”2 India’s rise, of course, has been heralded before—perhaps prematurely. How- ever, its ascent now seems assured in light of changes in India’s economic and political mind-set, especially the advent of better economic policies and a diplo- macy emphasizing realism. -

How Nations Learn Praise for the Book

How Nations Learn Praise for the Book ‘The chapters examine how industrial latecomers have crafted strategic and pragmatic policy frameworks to unleash the universal passion for learning into business organ- izational practices that drive production capability development and foster innovation dynamics. The transformational experiences described in the book offer a multitude of ways in which learning is organized and applied to advance a nation’s productive structures and build competitive advantage in the global economy.’ Michael H Best, Professor Emeritus, Author of How Growth Really Happens: The Making of Economic Miracles through Production, Governance and Skills, Winner of the 2018 Schumpeter Prize ‘The analysis of development and catching-up has finally shifted away from sur- real problems of ‘optimal’ market-driven allocation of resources, toward the processes of learning and capability accumulation. This is an important contribution in this perspec- tive: And yet another nail into the coffinofthe“Washington Consensus”.’ Giovanni Dosi, Professor of Economics, Scuola Superiore Sant’ Anna, Pisa, Italy ‘Industrialisation has always been fundamental to sustained economic growth. It separates the world into high and low-income economies. To create inclusive pros- perity, we urgently need to understand How Nations Learn. State-supported innovation is not only cardinal for catch-up, but also to abate climate breakdown (through crowding in new businesses, nurturing experimentation, and ensuring public benefits). By studying the economic history of technological advancement in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, this book makes a powerful case for industrial policy.’ Dr Alice Evans, Lecturer in International Development, King’s College London ‘How Nations Learn is a book based on big ideas. -

From Colonial Segregation to Postcolonial ‘Integration’ – Constructing Ethnic Difference Through Singapore’S Little India and the Singapore ‘Indian’

FROM COLONIAL SEGREGATION TO POSTCOLONIAL ‘INTEGRATION’ – CONSTRUCTING ETHNIC DIFFERENCE THROUGH SINGAPORE’S LITTLE INDIA AND THE SINGAPORE ‘INDIAN’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY BY SUBRAMANIAM AIYER UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY 2006 ---------- Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Thesis Argument 3 Research Methodology and Fieldwork Experiences 6 Theoretical Perspectives 16 Social Production of Space and Social Construction of Space 16 Hegemony 18 Thesis Structure 30 PART I - SEGREGATION, ‘RACE’ AND THE COLONIAL CITY Chapter 1 COLONIAL ORIGINS TO NATION STATE – A PREVIEW 34 1.1 Singapore – The Colonial City 34 1.1.1 History and Politics 34 1.1.2 Society 38 1.1.3 Urban Political Economy 39 1.2 Singapore – The Nation State 44 1.3 Conclusion 47 2 INDIAN MIGRATION 49 2.1 Indian migration to the British colonies, including Southeast Asia 49 2.2 Indian Migration to Singapore 51 2.3 Gathering Grounds of Early Indian Migrants in Singapore 59 2.4 The Ethnic Signification of Little India 63 2.5 Conclusion 65 3 THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLONIAL NARRATIVE IN SINGAPORE – AN IDEOLOGY OF RACIAL ZONING AND SEGREGATION 67 3.1 The Construction of the Colonial Narrative in Singapore 67 3.2 Racial Zoning and Segregation 71 3.3 Street Naming 79 3.4 Urban built forms 84 3.5 Conclusion 85 PART II - ‘INTEGRATION’, ‘RACE’ AND ETHNICITY IN THE NATION STATE Chapter -

Annual Report 2010-2011

Annual Report 2010-2011 Ministry of External Affairs New Delhi Published by: Policy Planning and Research Division, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi This Annual Report can also be accessed at website: www.mea.gov.in Designed and printed by: Cyberart Informations Pvt. Ltd. 1517 Hemkunt Chambers, 89 Nehru Place, New Delhi 110 019 E mail: [email protected] Website: www.cyberart.co.in Telefax: 0120-4231676 Contents Introduction and Synopsis i-xviii 1 India’s Neighbours 1 2 South East Asia and the Pacific 18 3 East Asia 26 4 Eurasia 32 5 The Gulf, West Asia and North Africa 41 6 Africa (South of Sahara) 50 7 Europe and European Union 66 8 The Americas 88 9 United Nations and International Organizations 105 10 Disarmament and International Security Affairs 120 11 Multilateral Economic Relation 125 12 SAARC 128 13 Technical and Economic Cooperation and Development Partnership 131 14 Investment and Technology Promotion 134 15 Energy Security 136 16 Policy Planning and Research 137 17 Protocol 140 18 Consular, Passport and Visa Services 147 19 Administration and Establishment 150 20 Right to Information and Chief Public Information Office 153 21 e-Governance and Information Technology 154 22 Coordination 155 23 External Publicity 156 24 Public Diplomacy 158 25 Foreign Service Institute 165 26 Implementation of Official Language Policy and Propagation of Hindi Abroad 167 27 Third Heads of Missions’ (HoMS) Conference 170 28 Indian Council for Cultural Relations 171 29 Indian Council of World Affairs 176 30 Research and Information -

Building ASEAN Community: Political–Security and Socio-Cultural Reflections

ASEAN@50 Volume 4 Building ASEAN Community: Political–Security and Socio-cultural Reflections Edited by Aileen Baviera and Larry Maramis Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia © Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic or mechanical without prior written notice to and permission from ERIA. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, its Governing Board, Academic Advisory Council, or the institutions and governments they represent. The findings, interpretations, conclusions, and views expressed in their respective chapters are entirely those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, its Governing Board, Academic Advisory Council, or the institutions and governments they represent. Any error in content or citation in the respective chapters is the sole responsibility of the author/s. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Cover Art by Artmosphere Design. Book Design by Alvin Tubio. National Library of Indonesia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN: 978-602-8660-98-3 Department of Foreign Affairs Kagawaran ng Ugnayang Panlabas Foreword I congratulate the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), the Permanent Mission of the Philippines to ASEAN and the Philippine ASEAN National Secretariat for publishing this 5-volume publication on perspectives on the making, substance, significance and future of ASEAN. -

Non Mil Stn HQ SEMO CO/SDO

REVISED COMMAND AND CONTROL MATRIX OF 426 ECHS POLYCLINICS AS ON 01 APR 2018 Ser Polyclinics Type Mil/ Stn HQ SEMO CO/SDO Service/ Sub Area Area Distt State Remarks No Non Mil (STATION DENTAL Comd ADVISER) Regional Centre Ahmedabad (16) 1 Jaisalmer D Mil AF Stn Jaisalmer 15 AFH, Jaisalmer 19 AFDC, Jodhpur AF SWAC - Jaisalmer Rajasthan 2 Ajmer D Mil Ajmer MH Nasirabad MDC, Nasirabad SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Ajmer Rajasthan 3 Barmer (Jalipa) D Mil Jalipa 177 MH Barmer 12 CDU, Jodhpur SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Barmer Rajasthan 4 Jodhpur B Mil Jodhpur MH Jodhpur 12 CDU, Jodhpur SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Jodhpur Rajasthan 5 Pali D Non Mil Jodhpur MH Jodhpur 12 CDU, Jodhpur SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Pali Rajasthan 6 Udaipur D Mil Udaipur 185 MH, Udaipur 12 CDU, Jodhpur SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Udaipur Rajasthan 7 Ahmedabad C Mil Ahmedabad MH Ahmedabad MDC, Vadodara SC UM&G SA MG&G Area Ahmedabad Gujarat 8 Jamnagar D Mil Jamnagar MH Jamnagar MDC, Vadodara SC UM&G SA MG&G Area Jamnagar Gujarat 9 Vadodra D Mil Vadodara MH Vadodara MDC, Vadodara SC UM&G SA MG&G Area Vadodara Gujarat 10 Bhuj D Non Mil Stn HQ Bhuj MH Bhuj MDC, Vadodara SC UM&G SA MG&G Area Kutch Gujarat 11 Bhilwara D Non Mil Ajmer MH Nasirabad MDC, Nasirabad SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Bhilwara Rajasthan 12 Shergarh D Non Mil Jodhpur MH Jodhpur 12 CDU, Jodhpur SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Jodhpur Rajasthan 13 Dungarpur D Non Mil Udaipur 185 MH Udaipur 12 CDU, Jodhpur SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Dungarpur Rajasthan 14 Rajsamand D Non Mil Udaipur 185 MH Udaipur 12 CDU, Jodhpur SC Jodhpur SA MG&G Area Rajsamand -

Cadet's Hand Book (Navy)

1 CADET’S HAND BOOK (NAVY) SPECIALISED SUBJECT 2 Preface 1. National Cadet Corps (NCC), came into existence, on 15 July 1948 under an Act of Parliament. Over the years, NCC has spread its activities and values, across the length and breadth of the country; in schools and colleges, in almost all the districts of India. It has attracted millions of young boys and girls, to the very ethos espoused by its motto, “unity and discipline” and molded them into disciplined and responsible citizens of the country. NCC has attained an enviable brand value for itself, in the Young India’s mind space. 2. National Cadet Corps (NCC), aims at character building and leadership, in all walks of life and promotes the spirit of patriotism and National Integration amongst the youth of the country. Towards this end, it runs a multifaceted training; varied in content, style and processes, with added emphasis on practical training, outdoor training and training as a community. 3. With the dawn of Third Millennia, there have been rapid strides in technology, information, social and economic fields, bringing in a paradigm shift in learning field too; NCC being no exception. A need was felt to change with times. NCC has introduced its New Training Philosophy, catering to all the new changes and developments, taking place in the Indian Society. It has streamlined and completely overhauled its training philosophy, objectives, syllabus, methodology etc, thus making it in sync with times. Subjects like National Integration, Personality Development and Life Skills, Social Service and Community Development activities etc, have been given prominent thrust. -

Abhyaas News Board … for the Quintessential Test Prep Student

February 5, 2017 ANB20170202 Abhyaas News Board … For the quintessential test prep student 68th Indian Republic Day celebrated The chief guest at the Republic Parade this year The Editor’s Column was Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi. Dear Student, A contingent of UAE soldiers marched in the parade. The 149-member Presidential Guard, The new year augurs a lot of new changes. Donald which was led by a UAE band consisting of 35 Trump takes office as the 45th President of USA. The musicians, presented a ceremonial salute to the world watches as he makes sweeping changes in his President and the Chief Guest. A contingent of the first few days in office. National Security Guard (NSG), popularly known as the Black Cat Commandos, also participated in the Padma Awards announced as India celebrated the 68th parade which was commanded by Lt General Republic Day. A departure from the norm, the Budget Manoj Mukund Naravane, General Officer has been presented on Feb 1st. Miss France wins the Commanding, Delhi Area. Miss Universe crown whereas Rogerer Federer wins The army showcased its Tank T-90 and Infantry his 18th Grand Slam title and Serena Williams her 23rd Combat Vehicle and Brahmos Missile, its Weapon title. Locating Radar Swathi, Transportable Satellite Terminal and Akash Weapon System. The Indian Vinod Rai takes over the new BCCI chief and the Air Force tableau had the theme "Air Dominance Chairman of the Tata Group is N Chandra. Through Network Centric Operations". The tableau displayed the scaled down models of Su-30 MKI, Mirage-2000, AWACS, UAV, Apache and Happy Reading !! Communication Satellite. -

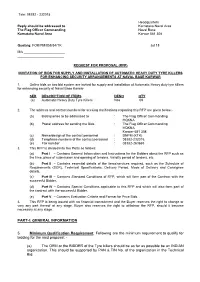

Following Are the Minimum Requirement to Qualify for Bidding for the Said Proposal:

Tele: 08382 - 232015 Headquarters Reply should be addressed to Karnataka Naval Area The Flag Officer Commanding Naval Base Karnataka Naval Area Karwar 581 308 Quoting: FOK/PM/858/54/TK Jul 18 M/s ______________________ _________________________ REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) INVITATION OF BIDS FOR SUPPLY AND INSTALLATION OF AUTOMATIC HEAVY DUTY TYRE KILLERS FOR ENHANCING SECURITY ARRANGEMENTS AT NAVAL BASE KARWAR 1. Online bids on two bid system are invited for supply and installation of Automatic Heavy duty tyre killers for enhancing security at Naval Base Karwar. SER DESCRIPTION OF ITEMS DENO QTY (a) Automatic Heavy Duty Tyre Killers Nos 09 2. The address and contact numbers for seeking clarifications regarding this RFP are given below:- (a) Bids/queries to be addressed to : The Flag Officer Commanding HQKNA (b) Postal address for sending the Bids : The Flag Officer Commanding HQKNA Karwar-581 308 (c) Name/design of the contact personnel : DNPM (KTK) (d) Telephone numbers of the contact personnel : 08382-232015, (e) Fax number : 08382-263665 3. This RFP is divided into five Parts as follows: (a) Part I – Contains General Information and Instructions for the Bidders about the RFP such as the time, place of submission and opening of tenders, Validity period of tenders, etc. (b) Part II – Contains essential details of the items/services required, such as the Schedule of Requirements (SOR), Technical Specifications, Delivery Period, Mode of Delivery and Consignee details. (c) Part III – Contains Standard Conditions of RFP, which will form part of the Contract with the successful Bidder. (d) Part IV – Contains Special Conditions applicable to this RFP and which will also form part of the contract with the successful Bidder. -

INS Vikramaditya

INS Vikramaditya History : Baku entered service in 1987, and was renamed Admiral Gorshkov in 1991, but was deactivated in 1996 because she was too expensive to operate on a post-Cold War budget. This attracted the attention of India, which was looking for a way to expand its carrier aviation capabilities.On 20 January 2004, after years of negotiations, Russia and India signed a deal for the sale of the ship. The ship would be free, while India would pay US$800 million for the upgrade and refit of the ship, as well as an additional US$1 billion for the aircraft and weapons systems. The navy looked at equipping the carrier with the E-2C Hawkeye, but decided not to. In 2009, Northrop Grumman offered the advanced E-2D Hawkeye to the Indian Navy. The deal also included the purchase of 12 single-seat Mikoyan MiG-29K 'Fulcrum-D' (Product 9.41) and four dual-seat MiG-29KUB aircraft (with an option for 14 more aircraft) at US$1 billion, six Kamov Ka-31 "Helix" reconnaissance and anti-submarine helicopters, torpedo tubes, missile systems and artillery units. Facilities and procedures for training pilots and technical staff, delivery of simulators, spare parts, and establishment maintenance on Indian Navy facilities were also part of the contract. The upgrade involved stripping all the weaponry and missile launcher tubes from the ship's foredeck to make way for a "short take-off but arrested recovery" (STOBAR) configuration, converting the Gorshkov from a hybrid carrier/cruiser to a pure carrier. Vikramaditya (left) alongside the Russian aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov in the port of Severomorsk in 2012 The announced delivery date for INS Vikramaditya was August 2008, which would allow the carrier to enter service just as the Indian Navy's only light carrier INS Viraat retired. -

DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS ARTICLE 08/07/2021 1. Project Seabird 2

DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS ARTICLE 08/07/2021 1. Project Seabird Q. Why is this in news? A. Defence Minister has recently visited the Karwar Naval Base in Karnataka to inspect infrastructure development under Phase II of “Project Seabird”. Q. What is Project Seabird? A. The largest naval infrastructure project for India, Project Seabird involves the creation of a naval base at Karwar on the west coast of India. INS Kadamba is an Indian Navy base located near Karwar in Karnataka. The first phase of construction of the base was code-named Project Seabird and was completed in 2005. INS Kadamba is currently the third-largest Indian naval base and is expected to become the largest naval base in the eastern hemisphere after the completion of expansion Phase IIB. Q. Why need such a base? A. During the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971, the Indian Navy faced security challenges for its Western Fleet in Mumbai Harbour due to congestion in the shipping lanes from commercial shipping traffic, fishing boats and tourists. At the end of the war, various options were considered on addressing these concerns Upon completion, it will provide the Indian Navy with its largest naval base on the west coast and also the largest naval base east of the Suez Canal. The Navy’s lone aircraft carrier INS Vikramaditya is based at Karwar. 2 Green Hydrogen Q. Why is this in news ? A. Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL) is investing Rs 75,000 crore in its new business focused on clean energy, which includes solar and green hydrogen. The company will build four giga factories focusing on solar, storage battery, green hydrogen and a fuel cell factory, which can convert hydrogen into mobile and stationary power. -

Daily Updated Current Affairs – 29.03.2017 to 31.03.2017

DAILY UPDATED CURRENT AFFAIRS – 29.03.2017 TO 31.03.2017 DAILY UPDATED CURRENT AFFAIRS NATIONAL b) The airlines selected under this round are SpiceJet, Air SC banned sale, registration of BS-III vehicles India subsidiary Alliance Air and regional airlines a) The Supreme Court has banned the sale and Turbo Megha Airways, Air Deccan and Air Odisha registration of Bharat Stage (BS)-III emission norm- Aviation compliant vehicles from April 1, 2017, with c) Some of the inactive airports selected are Shimla, environmentally friendly BS-IV emission norms will Bikaner, Agra, Gwalior, Rourkela, Kadapa, come into force across the country. Jharsuguda, Vidyanagar, Burnpur, Kullu, Diu, b) All the vehicle registering authorities under the Motor Mysore, Shillong, Jagdalpur, Salem, Utkela, and Vehicles Act, 1988 are prohibited from registering Hosur. such vehicles on and from April 1, 2017 that do not UDAN scheme meet BS-IV emission standards. UDAN is an innovative scheme to develop the c) Vehicles that have already been sold on or before regional aviation market. March 31, 2017 will be not included in this ban. It is a market-based mechanism in which airlines bid India became net exporter of Electricity for the first for seat subsidies. Under this scheme, half of the seats time on the plane will be capped at Rs. 2,500 per hour‟s According to CEA (Central Electricity Authority), India flight. has exported around 5,798 million units to Nepal, Government will subsidise the losses incurred by Bangladesh, and Myanmar during the current FY 2016-17. airlines flying to dormant airports by charging Rs.