Thesis Hum 2013 Horler Vivien.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eric L. Clements, Ph.D. Department of History, MS2960 Southeast Missouri State University Cape Girardeau, MO 63701 (573) 651-2809 [email protected]

Eric L. Clements, Ph.D. Department of History, MS2960 Southeast Missouri State University Cape Girardeau, MO 63701 (573) 651-2809 [email protected] Education Ph.D., history, Arizona State University. Fields in modern United States, American West, and modern Europe. Dissertation: “Bust: The Social and Political Consequences of Economic Disaster in Two Arizona Mining Communities.” Dissertation director: Peter Iverson. M.A., history, with museum studies certificate, University of Delaware. B.A., history, Colorado State University. Professional Experience Professor of History, Southeast Missouri State University, Cape Girardeau Missouri, July 2009 to the present. Associate Professor of History, Southeast Missouri State University, January 2008 through June 2009. Associate Professor of History and Assistant Director of the Southeast Missouri Regional Museum, Southeast Missouri State University, July 2005 to December 2007. Assistant Professor of History and Assistant Director of the university museum, Southeast Missouri State University, August 1999 to June 2005. Education Director, Western Museum of Mining and Industry, Colorado Springs, Colorado, February 1995 through June 1999. College Courses Taught to Date Graduate: American West, Material Culture, Introduction to Public History, Progressive Era Writing Seminar, and Heritage Education. Undergraduate: American West, American Foreign Relations, Colonial-Revolutionary America, Museum Studies Survey, Museum Studies Practicum, and early and modern American history surveys. Continuing Education: “Foundations of Colorado,” a one-credit-hour course for the Teacher Enhancement Program, Colorado School of Mines, 11 and 18 July 1998. Publications Book: After the Boom in Tombstone and Jerome, Arizona: Decline in Western Resource Towns. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2003. (Reissued in paperback, 2014.) Articles and Chapters: “Forgotten Ghosts of the Southern Colorado Coal Fields: A Photo Essay” Mining History Journal 21 (2014): 84-95. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

DR. BORLASE's ACCOUNT of LUDGVAN by P

DR. BORLASE'S ACCOUNT OF LUDGVAN By P. A. S. POOL, M.A. (Gwas Galva) R. WILLIAM BORLASE at one time intended to write a D parochial history of Cornwall, and for that purpose collected a large MS. volume of Parochial Memoranda, which is now pre• served at the British Museum (Egerton MSS. 2657). Although of great interest and importance, this consists merely of disjointed notes and is in no sense a finished product. But among Borlase's MSS. at the Penzance Library is a systematic and detailed account, compiled in 1770, of the parish of Ludgvan, of which he was Rector from 1722 until his death in 1772. This has never been published, and the present article gives a summary of its contents, with extracts. The account starts with a discussion of the derivation of the parish name, Borlase doubting the common supposition " that a native saint by his holiness and miracles distinguished it from other districts by his own celebrated name," and concluding that " the existence of such a person as St. Ludgvan . may well be accounted groundless." His own view was that the parish was called after the Manor of Ludgvan, which in turn derived its name from the Lyd or Lid, the name given in Harrison's Description of Britain (1577) to the stream running through the parish. It is noteworthy that the older Ludgvan people still, at the present day, pronounce the name " Lidjan." Borlase next gives the descent of the manor, the Domesday LUDUAM, through the families of Ferrers, Champernowne, Brook, Blount and Paulet. -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

Apprenticeship Vacancies in Cornwall

Information Classification: CONTROLLED Website: www.cornwallapprenticeships.com Email: [email protected] Apprenticeship Vacancies w/c 17th August 2020 (vacancies available to all age applicants, from age 16) *** This Week’s Featured Apprenticeship *** Boatbuilding and Marine Engineering Apprenticeships Cockwells Modern & Classic Boatbuilding Ltd Location: Falmouth Salary: n/k Are you looking to start a career in boatbuilding? Cockwells Modern & Classic Boatbuilding Ltd. Are looking for enthusiastic individuals to join our highly skilled team of craftsmen and women. Cockwells enjoy an enviable reputation as a company in the forefront of designing and building the highest quality boats, motor launches and tenders. The Company cleverly integrates traditional boatbuilding skills with innovative engineering and modern techniques to build custom and semi-production vessels of the highest quality using both wood and composite materials. Following a major investment and redevelopment of their established base at Mylor Creek near Falmouth, Cockwells is looking forward to exciting times ahead, creating new opportunities and investing in the future of the Company and its workforce. We are offering a fantastic opportunity to become an apprentice in either: Boatbuilding or Marine Engineering. Closing date: n/k Possible start date: n/k To apply visit https://cockwells.co.uk/discover/careers/ Teaching Assistance Apprentice (x3 positions available) Berrycoombe School Location: Bodmin Salary: £124.50 We are looking for three apprentice Teaching Assistants to work in our primary school located in Bodmin. We have 223 pupils and are a welcoming, friendly school situated alongside the lovely Camel Trail, which links in nicely with our Forestry lessons. We are offering a broad and balanced experience across the school and 1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED developing both KS1 and KS2 practice. -

Weeklies with Local Cartoons Are 'Truly Blessed'

Weeklies with local cartoons are ‘truly blessed’ By Marcia Martinek . Pages 1-3 Funding of journalism remains the Holy Grail By Anthony Longden . Pages 4-6 Fighting spirit: Competing hyperlocal sites outmatch regional newspaper’s community coverage By Barbara Selvin . Page 7-11 Extension journalism: Teaching students the real world and bringing a new type of journalism to a small town By Al Cross . Pages 12-18 Shared views: Social capital, community ties and Instagram By Leslie-Jean Thornton . Page 19-26 The EMT of multimedia: How to revive your newspaper’s future By Teri Finneman . Pages 27-32 volume 54, no. 3-4 • fall/winter 2013 grassroots editor • fall-winter 2013 Weeklies with local Editor: Dr. Chad Stebbins Graphic Designer: Liz Ford Grassroots Editor cartoons are ‘truly blessed’ (USPS 227-040, ISSN 0017-3541) is published quarterly for $25 per year by By Marcia Martinek the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors, Institute of International Studies, Missouri Southern When an 8-year-old girl saw an illustration in the Altamont (New York) Enterprise depict- State University, 3950 East Newman Road, ing her church, which was being closed by the Albany Diocese, she became upset. Forest Byrd, Joplin, MO 64801-1595. Periodicals post- then the illustrator for the newspaper, had drawn the church with a tilting steeple, being age paid at Joplin, Mo., and at strangled with vines as a symbol of what was happening in the diocese. additional mailing offices. The girl wrote to the newspaper, and Editor Melissa Hale-Spencer responded to her, explaining the role of cartoons in a newspaper along with affirming the girl’s action in writing POSTMASTER: Send address changes the letter. -

14-November-2014

November 14 2014 / 21 Cheshvan 5775 Volume 18 – Number 39 Jack south african Ginsberg, art philanthropist, celebrated (page 5). Jewish Report www.sajr.co.za Photo: Flash90 Photo: Vehicles used as a terrorist weapon The scene where a car crashed into Jerusalem’s Ammunition Hill in a Palestinian terrorist attack on October 22 when Abdel Rachman al-Shaludi rammed his car into a crowd at a Jerusalem light rail station, killing two people, one a three-month-old baby and the other SA-born Dalya Lemkus. In a new pattern of using vehicles as “terrorist weapons”, on November 5 another terrorist, Ibrahim al-Akari used his van as a weapon against pedestrians, killing two more people. The seemingly randomness of the attacks is particularly terrifying. The two terrorists have both been lauded as “heroes” by Palestinian Media Watch. Stronger action by American lawmakers has been urged to curb this trend. See page 7 BDS support: 2 Progressive Cosas students get their Sevitz leaves UOS after Sackstein: SA Jews have Through memorial, rabbis cause huge furore wings firmly clipped restructuring become ‘slacktavists’ Mauritian Jewish presence instead of ‘activists’ will live on Although our Progressive rabbis Cosas is “extremely angry The first inclination of changes bend over backwards to reiterate at Woolworths’ pigheaded at the UOS, came last week on How is it that we have a No longer can or will a wall, or a their support for gay congregants, management”, and stressed that the Kashrut-SA Facebook page, community that has gone from the man, have the power to deny you I am increasingly uncomfortable their “logic behind the pig head on which Sevitz has built a huge most politically activist in the past, your freedom, your privacy, your with their trend politicising their initiative was not against particular following, when he posted a to the most passive of bystanders right to life, your right to live with pulpit. -

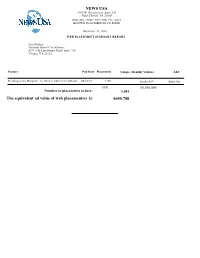

NEWS USA the Equivalent Ad Value of Web Placement(S)

NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 WEB PLACEMENT SUMMARY REPORT Lisa Fullam National Blood Clot Alliance 8321 Old Courthouse Road, Suite 255 Vienna, VA 22182 Feature Pub Date Placements Unique Monthly Visitors AEV Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood 08/10/16 1,001 50,058,999 $600,708 1001 50,058,999 Number of placements to date: 1,001 The equivalent ad value of web placement(s) is: $600,708 NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 National Blood Clot Alliance--Fullam WEB PLACEMENTS REPORT Feature: Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood Clot. Publication Date: 8/10/16 Unique Monthly Web Site City, State Date Vistors AEV 760 KFMB San Diego, CA 08/11/16 4,360 $52.32 96.5 Wazy ::: Today's Best Music, Lafayette Indiana Lafayette, IN 08/12/16 280 $3.36 Aberdeen American News Aberdeen, SD 08/11/16 14,800 $177.60 Abilene-rc.com Abilene, KS 08/11/16 0 $0.00 About Pokemon Go Cirebon, ID 09/08/16 0 $0.00 Advocate Tribune Online Granite Falls, MN 08/11/16 37,855 $454.26 aimmediatexas.com/ McAllen, TX 08/11/16 920 $11.04 Alerus Retirement Solutions Arden Hills, MN 08/12/16 28,400 $340.80 Alestle Live Edwardsville, IL 08/11/16 1,640 $19.68 Algona Upper Des Moines Algona, IA 08/11/16 680 $8.16 Amery Free Press. -

2018-09-Agenda

LUDGVAN PARISH COUNCIL This is to notify you that the Monthly Meeting of Ludgvan Parish Council will be held on Wednesday 12th September, 2018 in the Oasis Childcare Centre, Lower Quarter, Ludgvan commencing at 7pm. M J Beveridge Parish Clerk 07/09/2018 AGENDA: Page No. Public Participation Period (if required) 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting on Wednesday, 8th August, 3-6 2018 3. Declarations of interest in Items on the Agenda 4. Dispensations 5. Councillor Reports (a) Cornwall Councillor Simon Elliott (b) Chairman's report (c) Other Councillors REPORTS FOR DECISION 6. Cornwall Council – Planning Applications To access the applications go to: http://planning.cornwall.gov.uk/online- applications and enter the PA number into the search. (a) PA18/07223 – Polpeor Villa, Wheal Kitty Road, Lelant Downs TR27 6NS – Erection of ancillary accommodation – Ms L Bree (b) PA18/07053 – Land Rear To Louraine House, Crowlas, Cornwall TR20 8DS – Construction of 6 Dwelling Houses, Access Road, Landscaping, Community Gardens & Associated Works (Three Affordable) – Mrs L Trudgeon (c) PA18/07785 – 6 Trethorns Court, Ludgvan TR20 8HE – Replace first floor balcony with first floor extension and Juliet balcony – Dr and Mrs Nigel and Jane Haward 7. Clerk’s Report (a) AGAR – External Auditor’s Report, see attached. 7 (b) Allotments: (i) Working Party recommendations, see attached. 8-9 (ii) Long Rock allotments wall – go ahead from St Aubyn’s 10 Estates. See background report, attached. (c) CC, Planning Conference for Local Councils, St Johns Hall - £12 cost – Thurs, 4 October, 2018 (d) Local Landscape Character Assessment – Delay in roll out to November (e) Defibrillator training (f) Silver footpath 43, sections 1 and 3 between Canonstown’s Heather Lane and Lelant Downs. -

Hoover Dam) on the Colorado River Nearby in the 1930S Brought the Electric Power and Water on Which the Modern Metropolis Depends

The Rockies • The Rocky Mountains , commonly known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range in western North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch more than 3,000 miles (4,830 km) from the northernmost part of British Columbia, in western Canada, to New Mexico, in the southwestern United States. The Rockies are somewhat distinct from theCascade Range and Sierra Nevada which all lie farther to the west. • Currently, much of the mountain range is protected by public parks and forest lands, and is a popular tourist destination, especially for hiking, camping, mountaineering, fishing, hunting, mountain biking, skiing, and snowboarding. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocky_Mountains The Rockies • Apart from the Ancestral Puebloan cliff-dwellers, who lived in southern Colorado until around 1300 AD, most Native Americans in this region were nomadic hunters. They inhabited the western extremities of the Great Plains, the richest buffalo-grazing land in the continent. • Only after the territory was sold to the US in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase was it thoroughly charted, starting with the Lewis and Clark expedition that traversed Montana and Idaho in 1805. As a result of the team’s reports of abundant game, the fabled “ mountain men ” had soon trapped the beavers here to the point of virtual extinction. They left as soon as the pelt boom was over, however, and permanent white settlement did not begin until gold was discovered near Denver in 1858. • Within a decade, speculators were plundering every accessible gorge and creek in the four states in the search for valuable ores. The construction of transcontinental rail lines and the establishment of vast cattle ranches to feed the mining camps led to the slaughter of millions of buffalo, and conflict with the Native Americans became inevitable. -

2016-Annual-Report.Pdf

2016ANNUAL REPORT PORTFOLIO OVE RVIEW NEW MEDIA REACH OF OUR DAILY OPERATE IN O VER 535 MARKETS N EWSPAPERS HAVE ACR OSS 36 STATES BEEN PUBLISHED FOR 100% MORE THAN 50 YEARS 630+ TOTAL COMMUNITY PUBLICATIONS REACH OVER 20 MILLION PEOPLE ON A WEEKLY BASIS 130 D AILY N EWSPAPERS 535+ 1,400+ RELATED IN-MARKET SERVE OVER WEBSITES SALES 220K REPRESENTATIVES SMALL & MEDIUM BUSINESSES SAAS, DIGITAL MARKETING SERVICES, & IT SERVICES CUMULATIVE COMMON DIVIDENDS SINCE SPIN-OFF* $3.52 $3.17 $2.82 $2.49 $2.16 $1.83 $1.50 $1.17 $0.84 $0.54 $0.27 Q2 2014 Q3 2014 Q4 2014 Q1 2015 Q2 2015 Q3 2015 Q4 2015 Q1 2016 Q2 2016 Q3 2016 Q4 2016 *As of December 25, 2016 DEAR FELLOW SHAREHOLDERS: New Media Investment Group Inc. (“New Media”, “we”, or the “Company”) continued to execute on its business plan in 2016. As a reminder, our strategy includes growing organic revenue and cash flow, driving inorganic growth through strategic and accretive acquisitions, and returning a substantial portion of cash to shareholders in the form of a dividend. Over the past three years since becoming a public company, we have consistently delivered on this strategy, and we have created a total return to shareholders of over 50% as of year-end 2016. Our Company remains the largest owner of daily newspapers in the United States with 125 daily newspapers, the majority of which have been published for more than 100 years. Our local media brands remain the cornerstones of their communities providing hyper-local news that our consumers and businesses cannot get anywhere else. -

National List

NATIONAL LIST 1 Otta Helen Maree 2 Mmoba Solomon Seshoka 3 Lindiwe Desire Mazibuko 4 Suhla James Masango 5 Joseph Job Mcgluwa 6 Andrew Grant Whitfield 7 Semakaleng Patricia Kopane 8 Gregory Allen Grootboom 9 Dion Travers George 10 David John Maynier 11 Desiree van der Walt 12 Gregory Rudy Krumbock 13 Tarnia Elena Baker 14 Leonard Jones Basson 15 Zisiwe Beauty Nosimo Balindlela 16 Annelie Lotriet 17 Dirk Jan Stubbe 18 Anchen Margaretha Dreyer 19 Phumzile Thelma Van Damme 20 Stevens Mokgalapa 21 Michael John Cardo 22 Stanford Makashule Gana 23 Mohammed Haniff Hoosen 24 Gavin Richard Davis 25 Kevin John Mileham 26 Natasha Wendy Anita Michael 27 Denise Robinson 28 Werner Horn 29 Ian Michael Ollis 30 Johanna Fredrika Terblanche 31 Hildegard Sonja Boshoff 32 Lance William Greyling 33 Glynnis Breytenbach 34 Robert Alfred Lees 35 Derrick America 36 James Robert Bourne Lorimer 37 Terri Stander 38 Evelyn Rayne Wilson 39 James Vos 40 Thomas Charles Ravenscroft Walters 41 Veronica van Dyk 42 Cameron MacKenzie 43 Tandeka Gqada 44 Dianne Kohler 45 Darren Bergman 46 Zelda Jongbloed 47 Annette Steyn 48 Sejamotopo Charles Motau 49 David Christie Ross 50 Archibold Mzuvukile Figlan 51 Michael Waters 52 John Henry Steenhuisen 53 Choloane David Matsepe 54 Santosh Vinita Kalyan 55 Hendrik Christiaan Crafford Kruger 56 Johanna Steenkamp 57 Annette Theresa Lovemore 58 Nomsa Innocencia Tarabella Marchesi 59 Karen De Kock 60 Heinrich Cyril Volmink 61 Michael Bagraim 62 Gordon Mackay 63 Erik Johannes Marais 64 Marius Helenis Redelinghuys 65 Lungiswa Veronica James