Shabbat and Rosh Hashanah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Choosing an Influence, Or Bach the Inexhaustible: the Heterophony of the Voices of Twentieth- Century Composers”

Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online, Vol. 13, 2015-16 Yulia Kreinin -“Choosing an Influence, or Bach the Inexhaustible: The Heterophony of the Voices of Twentieth- Century Composers” “Choosing an Influence, or Bach the Inexhaustible: The Heterophony of the Voices of Twentieth-Century Composers” YULIA KREININ Bach’s influence on posterity has been evident for over 250 years. In fact, since 1829, the year of Mendelssohn’s historic performance of the St. Matthew Passion, Bach has been one of the most respected figures in European musical culture. By the start of the twentieth century, Bach’s cultural presence was a given. Nevertheless, the twentieth century witnessed a new stage in the appreciation and understanding of Bach. In the first half of the century, “Back to Bach” was a significant motto for two waves of neoclassicism. From the 1960s on, Bach’s passion genre tradition was revived and reinterpreted, while other forms of homage to him blossomed (preludes and fugues, concerti grossi, works for solo strings). Composers’ spiritual dialogue with Bach took on a new importance. In this context, it is appropriate to investigate the reason(s) for the unique persistence of Bach’s influence into the twentieth century, an influence that surpasses that of other major composers of the past, including Mozart and Beethoven. Many scholars have addressed this conundrum; musicological research on Bach’s influence can be found in the four volumes of Bach und die Nachwelt (English, “Bach and Posterity”), published in Germany,1 and the seven volumes of Bach Perspectives, published in the United States.2 Nevertheless, “Why Bach?” has found only a partial answer and merits further examination. -

Sportscene | Fall 2014

THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF MACCABI USA VOLUME 11 | NUMBER 2 | FALL 2014 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE professional Basketball for Israel’s Super 2 David Blatt’s League. He continued to play professionally SEEKING JEWISH ATHLETES Maccabiah until 1993, when he transitioned to what 3 ROBERT E. SPIVAK Experience continues to be a stellar coaching career. LEADERSHIP AWARD “Playing for your country in the Maccabiah Games is a totally different VOLUNTEER PROFILE Influenced His Life Decisions experience than playing in college or 4 DONOR PROFILE professionally,” David said. “It’s about David first got involved with the sport of RECENT EVENTS more than just the competition; it is about Basketball as a small child. He watched immersing yourself in Jewish culture 5 UPCOMING EVENTS his older sisters practice the game using and gives you a sense of community and the basket their dad had installed over the MULTI-GENERATION togetherness. It’s an experience that stays 6 MACCABI USA FAMILIES garage and joined in. He fell in love with the with you always and is one of the main game and it’s been a lifelong affair. reasons I made Aliyah and have lived in LEGENDS OF THE MACCABIAH While playing point guard at Princeton, Israel the last 33 years.” 8 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE David was recruited by a coach from an In 1991, David married Kineret and Israeli kibbutz team, and he played in Israel EUROPEAN BASKETBALL together they are raising four children, INSIDE THIS ISSUE 9 that summer at Kibbutz Gan Shmuel. The Tamir, Shani, Ela and Adi. His son Tamir NEWS following year, a Maccabi USA volunteer competed for Israel at the 2013 Maccabiah 10 approached him about trying out for the Games as a member of the Juniors Boys’ USA Maccabiah team. -

Yom Kippur Morning Sinai Temple Springfield, Massachusetts October 12, 2016

Yom Kippur Morning Sinai Temple Springfield, Massachusetts October 12, 2016 Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die...?1 Who shall live and who shall die...? It was but a few weeks from the pulpit of Plum Street Temple in Cincinnati and my ordination to the dirt of Fort Dix, New Jersey, and the “night infiltration course” of basic training. As I crawled under the barbed wire in that summer night darkness illumined only by machine-gun tracer-fire whizzing overhead, I heard as weeks before the voice of Nelson Glueck, alav hashalom, whispering now in the sound of the war-fury ever around me: carry this Torah to amkha, carry it to your people. Who shall live and who shall die...? I prayed two prayers that night: Let me live, God, safe mikol tzarah v’tzukah, safe from all calamity and injury; don’t let that 50-calibre machine gun spraying the air above me with live ammunition break loose from its concrete housing. And I prayed once again. Let me never experience this frightening horror in combat where someone will be firing at me with extreme prejudice. Who shall live and who shall die...? I survived. The “terror [that stalks] by night” and “the arrow that flies by day” did not reach me.”2 The One who bestows lovingkindnesses on the undeserving carried me safely through. But one of my colleagues was not so lucky. He was a Roman Catholic priest. They said he died from a heart attack on the course that night. I think he died from fright. -

Framing Croatia's Politics of Memory and Identity

Workshop: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER WORKSHOP: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER Author: Taylor A. McConnell, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh Title: “KRVatska”, “Branitelji”, “Žrtve”: (Re-)framing Croatia’s politics of memory and identity Date: 3 April 2018 Workshop: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER “KRVatska”, “Branitelji”, “Žrtve”: (Re-)framing Croatia’s politics of memory and identity Taylor McConnell, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh Web: taylormcconnell.com | Twitter: @TMcConnell_SSPS | E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper explores the development of Croatian memory politics and the construction of a new Croatian identity in the aftermath of the 1990s war for independence. Using the public “face” of memory – monuments, museums and commemorations – I contend that Croatia’s narrative of self and self- sacrifice (hence “KRVatska” – a portmanteau of “blood/krv” and “Croatia/Hrvatska”) is divided between praising “defenders”/“branitelji”, selectively remembering its victims/“žrtve”, and silencing the Serb minority. While this divide is partially dependent on geography and the various ways the Croatian War for Independence came to an end in Dalmatia and Slavonia, the “defender” narrative remains preeminent. As well, I discuss the division of Croatian civil society, particularly between veterans’ associations and regional minority bodies, which continues to disrupt amicable relations among the Yugoslav successor states and places Croatia in a generally undesired but unshakable space between “Europe” and the Balkans. 1 Workshop: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Lyre of the Levites: Klezmer Music for Biblical Lyre

LYRE OF THE LEVITES: KLEZMER MUSIC FOR BIBLICAL LYRE "Lyre of the Levites: Klezmer Music for Biblical Lyre" is the sequel album to "King David's Lyre; Echoes of Ancient Israel". Both of these albums are dedicated to recreating again, for the first time in almost 2000 years, the mystical, ancient sounds of the "Kinnor"; the Hebrew Temple Lyre, once played by my very own, very ancient Levite ancestors in the Courtyard of the Temple of Jerusalem, to accompany the singing of the Levitical Choir (II Chronicles 5:12)... THE CHOICE OF REPERTOIRE FOR THE ALBUM "Lyre of the Levites" uniquely features arrangements of primarily traditional melodies from the Jewish Klezmer repertoire arranged for solo Levitical Lyre - the concept of the musical performances on this album, are meant to be evocations, not reconstructions, of the sounds & playing techniques that were possible on the ten-stringed Kinnor of the Bible; there are sadly too few unambiguously notated melodies from antiquity to make an album of "note for note" reconstructions of ancient instrumental solo lyre music a feasible reality. However, the traditional Jewish scales/modes in which these pieces are actually written may well have roots which stretch deeply back to these distant, mystically remote Biblical times, according to the fascinating research of the late Suzanne Haik Vantoura, in attempting to reconstruct the original 3000 year old music of the Hebrew Bible. THE TWELVE TRACKS There are 12 tracks to the album - corresponding to the 12 Gems which once adorned the Breastplate of the Levitical Priests of the Temple of Jerusalem. These 12 Gems represented the 12 Tribes of Israel. -

Silent Auction 2015 Catalogue V4-18

A Time(eit lintoa)to Plant Growing the Fruits of Community ANNUAL SILENT IVE & LMay 16,AUCTION 2015 Torah Education Social Justice Worship Music NORTHERN VIRGINIA HEBREW CONGREGATION www.nvhcreston.org Since 1990, we have worked hard to deliver the best possible designs and construction experience in Northern Virginia for the best value. -Bruce and Wilma Bowers Renovations | New Homes| 703.506.0845 | BowersDesiignBuild.com NORTHERN VIRGINIA HEBREW CONGREGATION WELCOME TO NVHC’S 9TH ANNUAL SILENT AND LIVE AUCTION Dear Friends, This year’s auction theme, “A Time to Plant, Growing the Fruits of Community,” beautifully captures who we are at NVHC, a community of givers. We give of our time. We give of our friendship. We give of our hearts. We give of our prayers. We give of our hard earned money. We give of our belief in our Jewish community and a better world today and in the future. What we receive in return for all this giving is a deep sense of purpose and lives more meaningfully lived. The auction is a community celebration, a party, and an important fundraiser for NVHC operations. Please be generous and absolutely have a wonderful time! I want to thank the auction committee for its hard work and dedication. I also thank everyone who has donated, purchased advertising, underwritten the expenses of the auction, or purchased a raffle ticket. All of these are integral to the success of the auction and the well-being of our community. Sincerely, David Selden President, NVHC Board of Trustees 1 NORTHERN VIRGINIA HEBREW CONGREGATION SILENT AND LIVE AUCTION RULES 1 All sales are final. -

Counterpoint | Music | Britannica.Com

SCHOOL AND LIBRARY SUBSCRIBERS JOIN • LOGIN • ACTIVATE YOUR FREE TRIAL! Counterpoint & READ VIEW ALL MEDIA (6) VIEW HISTORY EDIT FEEDBACK Music Written by: Roland John Jackson $ ! " # Counterpoint, art of combining different melodic lines in a musical composition. It is among the characteristic elements of Western musical practice. The word counterpoint is frequently used interchangeably with polyphony. This is not properly correct, since polyphony refers generally to music consisting of two or more distinct melodic lines while counterpoint refers to the compositional technique involved in the handling of these melodic lines. Good counterpoint requires two qualities: (1) a meaningful or harmonious relationship between the lines (a “vertical” consideration—i.e., dealing with harmony) and (2) some degree of independence or individuality within the lines themselves (a “horizontal” consideration, dealing with melody). Musical theorists have tended to emphasize the vertical aspects of counterpoint, defining the combinations of notes that are consonances and dissonances, and prescribing where consonances and dissonances should occur in the strong and weak beats of musical metre. In contrast, composers, especially the great ones, have shown more interest in the horizontal aspects: the movement of the individual melodic lines and long-range relationships of musical design and texture, the balance between vertical and horizontal forces, existing between these lines. The freedoms taken by composers have in turn influenced theorists to revise their laws. The word counterpoint is occasionally used by ethnomusicologists to describe aspects of heterophony —duplication of a basic melodic line, with certain differences of detail or of decoration, by the various performers. This usage is not entirely appropriate, for such instances as the singing of a single melody at parallel intervals (e.g., one performer beginning on C, the other on G) lack the truly distinct or separate voice parts found in true polyphony and in counterpoint. -

JABOTINSKY on CANADA and the Unlted STATES*

A CASE OFLIMITED VISION: JABOTINSKY ON CANADA AND THE UNlTED STATES* From its inception in 1897, and even earlier in its period of gestation, Zionism has been extremely popular in Canada. Adherence to the movement seemed all but universal among Canada's Jews by the World War I era. Even in the interwar period, as the flush of first achievement wore off and as the Canadian Jewish community became more acclimated, the movement in Canada functioned at a near-fever pitch. During the twenties and thirties funds were raised, acculturatedJews adhered toZionism with some settling in Palestine, and prominent gentile politicians publicly supported the movement. The contrast with the United States was striking. There, Zionism got a very slow start. At the outbreak of World War I only one American Jew in three hundred belonged to the Zionist movement; and, unlike Canada, a very strong undercurrent of anti-Zionism emerged in the Jewish community and among gentiles. The conversion to Zionism of Louis D. Brandeis-prominent lawyer and the first Jew to sit on the United States Supreme Court-the proclamation of the Balfour Declaration, and the conquest of Palestine by the British gave Zionism in the United States a significant boost during the war. Afterwards, however, American Zionism, like the country itself, returned to "normalcy." Membership in the movement plummeted; fundraising languished; potential settlers for Palestine were not to be found. One of the chief impediments to Zionism in America had to do with the nature of the relationship of American Jews to their country. Zionism was predicated on the proposition that Jews were doomed to .( 2 Michuel Brown be aliens in every country but their own. -

Nationalism in a Transnational Context: Croatian Diaspora, Intimacy and Nationalist Imagination

Nationalism in a Transnational Context: Croatian Diaspora, Intimacy and Nationalist Imagination ZLATKO SKRBIŠ UDK: 325.1/.2(94 = 163.42) School of Social Science 159.922.4:325.2(94 = 163.42) University of Queensland Izvorni znanstveni rad Australia Primljeno: 15. 10. 2001. E-mail: [email protected] This paper contributes to existing debates on the significance of modem diasporas in the context of global politics. In particular, it examines how nationalism has adapted to the newly emerging transnational environment. The new type of nationalism, long-distance nationalism, utilises modern forms of communication and travel to sustain its potency and relevance. Long-distance nationalism is not a simple consequence of global and transnational commu nication, but involves complex cultural, political and symbolic processes and practices.The first part of this paper examines some theoretical issues pertaining to the intersection between nationalism and transnational environments. It shows how nationalism is not antithetical to globalising and transnationalising tendencies, but instead, that it is becoming adapted to these new social conditions. In order to move beyond a rather simple assertion that trans nationalism and nationalism are safely co-existing, the paper argues that such cases of symbi osis are always concrete and ethnographically documentable. This paper grew out of the need to both assert the co-existing nature of nationalism and transnationalism and to provide a concrete example of nationalist sentiments in a modem transnational setting. This latter aim represents the core of the second part of the paper, which is based on research among second generation Croatians in Australia. It specifically explores the under-examined question of how nationalist sentiments inform and define people’s intimacy and marriage choices. -

(Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014

7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Rabbi Marcelo Kormis 30 Sessions Notes to Parents: This curriculum contains the knowledge, skills and attitude Jewish students are expected to learn. It provides the learning objectives that students are expected to meet; the units and lessons that teachers teach; the books, materials, technology and readings used in a course; and the assessments methods used to evaluate student learning. Some units have a large amount of material that on a given year may be modified in consideration of the Jewish calendar, lost school days due to weather (snow days), and give greater flexibility to the teacher to accommodate students’ pre-existing level of knowledge and skills. Page 1 of 16 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 Part 1 Musaguim – A Vocabulary of Jewish Life 22 Sessions The 7th grade curriculum will focus on basic musaguim of Jewish life. These musaguim cover the different aspects and levels of Jewish life. They can be divided into 4 concentric circles: inner circle – the day of a Jew, middle circle – the week of a Jew, middle outer circle – the year of a Jew, outer circle – the life of a Jew. The purpose of this course is to teach students about the different components of a Jewish day, the centrality of the Shabbat, the holidays and the stages of the life cycle. Focus will be placed on the Jewish traditions, rituals, ceremonies, and celebrations of each concept. Lifecycle events Jewish year Week - Shabbat Day Page 2 of 16 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 Unit 1: The day of a Jew: 6 sessions, 45 minute each. -

Tadir and Mekudash

` בס"ד Volume 17 Issue 5 Tadir and Mekudash The tenth perek discusses the order of precedence regarding since the Torah equated the korbanot that are brought for the the offering of korbanot or parts of korbanot. The first mussaf of Rosh Chodesh. Consequently, no proof can be Mishnah establishes that that which is performed more brought the order of mussaf offerings. frequently (tadir) comes first. For example, the daily offering is always offered before the mussaf offering. Indeed, the Gemara (90b) asks our question and leaves the Similarly, the mussaf offering that is brought on Shabbat is matter unresolved. The Rambam consequently rules that offered prior to the mussaf for Rosh Chodesh (when Rosh either may be selected. Nevertheless, the question continues Chodesh falls on Shabbat). to be discussed in other areas of halacha. The second Mishnah provides another rule, that if one is One example is the questions of which should be donned faced with two different korbanot, the more mekudash is first, a tallit or tefillin; the tallit is warn more frequently, offered. The Mishnayot continue by fleshing out this while the tefillin is more mekudash. concept, detailing the order of kedusha as it applies to The Nemukei Yosef maintains that tzitzit should be worn first. korbanot. One example relevant for our discussion is that the Firstly, it is considered equivalent to all mitzvot. blood from a chatat precedes the blood from an olah, since Furthermore, it warn more frequently. The Shagaat Aryeh the blood from a chatat achieves an atonement for the owner. (28) however finds this difficult. -

22-10-2018.Pdf

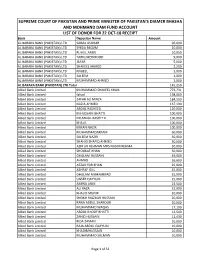

SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN AND PRIME MINISTER OF PAKISTAN'S DIAMER BHASHA AND MOHMAND DAM FUND ACCOUNT LIST OF DONOR FOR 22 OCT-18 RECEIPT Bank Depositor Name Amount AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SAIMA ASGHAR 96,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SYEDA BEGUM 20,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD RUHUL AMIN 10,050 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD TARIQ MEHMOOD 9,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD JAFAR 5,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SHAKEEL AHMED 2,200 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD NABEEL 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SALEEM 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD MUHAMMAD AHMED 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD Total 145,250 Allied Bank Limited MUHAMMAD SHAKEEL KHAN 773,731 Allied Bank Limited fahad 198,000 Allied Bank Limited ZAFAR ALI MIRZA 184,500 Allied Bank Limited NAZIA AHMED 137,190 Allied Bank Limited ABDUL RASHEED 120,000 Allied Bank Limited M HUSSAIN BHATTI 100,000 Allied Bank Limited DR.ABDUL RASHEED 100,000 Allied Bank Limited KHALIL 100,000 Allied Bank Limited IMRAN NAZIR 100,000 Allied Bank Limited MUHAMMADAKRAM 60,000 Allied Bank Limited SALEEM NAZIR 50,000 Allied Bank Limited SHAHID SHAFIQ AHMED 50,000 Allied Bank Limited AZIR UR REHMAN MRS NASIM REHMA 50,000 Allied Bank Limited SHOUKAT KHAN 50,000 Allied Bank Limited GHULAM HUSSAIN 49,000 Allied Bank Limited AHMAD 26,600 Allied Bank Limited AEZAD YAR KHAN 25,000 Allied Bank Limited ASHRAF GILL 25,000 Allied Bank Limited GHULAM MUHAMMAD 25,000 Allied Bank Limited UNSER QAYYUM 25,000 Allied Bank Limited AMINA ASIM 23,500 Allied Bank Limited ALI RAZA 23,000 Allied Bank