The Application of Voxel Size Correction in X-Ray Computed Tomography for Dimensional Metrology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Voxel Cone Tracing with Interleaved Sample Patterns by Sanghyeok Hong

c 2015, SangHyeok Hong. All Rights Reserved. The material presented within this document does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Committee, the Graduate Study Program, or DigiPen Institute of Technology. TEMPORAL VOXEL CONE TRACING WITH INTERLEAVED SAMPLE PATTERNS BY SangHyeok Hong THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science awarded by DigiPen Institute of Technology Redmond, Washington United States of America March 2015 Thesis Advisor: Gary Herron DIGIPEN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAM DEFENSE OF THESIS THE UNDERSIGNED VERIFY THAT THE FINAL ORAL DEFENSE OF THE MASTER OF SCIENCE THESIS TITLED Temporal Voxel Cone Tracing with Interleaved Sample Patterns BY SangHyeok Hong HAS BEEN SUCCESSFULLY COMPLETED ON March 12th, 2015. MAJOR FIELD OF STUDY: COMPUTER SCIENCE. APPROVED: Dmitri Volper date Xin Li date Graduate Program Director Dean of Faculty Dmitri Volper date Claude Comair date Department Chair, Computer Science President DIGIPEN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAM THESIS APPROVAL DATE: March 12th, 2015 BASED ON THE CANDIDATE'S SUCCESSFUL ORAL DEFENSE, IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE THESIS PREPARED BY SangHyeok Hong ENTITLED Temporal Voxel Cone Tracing with Interleaved Sample Patterns BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AT DIGIPEN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY. Gary Herron date Xin Li date Thesis Committee Chair Thesis Committee Member Pushpak Karnick date Matt -

Human Body Model Acquisition and Tracking Using Voxel Data

Submitted to the International Journal of Computer Vision Human Body Model Acquisition and Tracking using Voxel Data Ivana Mikić2, Mohan Trivedi1, Edward Hunter2, Pamela Cosman1 1Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of California, San Diego 2Q3DM, Inc. Abstract We present an integrated system for automatic acquisition of the human body model and motion tracking using input from multiple synchronized video streams. The video frames are segmented and the 3D voxel reconstructions of the human body shape in each frame are computed from the foreground silhouettes. These reconstructions are then used as input to the model acquisition and tracking algorithms. The human body model consists of ellipsoids and cylinders and is described using the twists framework resulting in a non-redundant set of model parameters. Model acquisition starts with a simple body part localization procedure based on template fitting and growing, which uses prior knowledge of average body part shapes and dimensions. The initial model is then refined using a Bayesian network that imposes human body proportions onto the body part size estimates. The tracker is an extended Kalman filter that estimates model parameters based on the measurements made on the labeled voxel data. A voxel labeling procedure that handles large frame-to-frame displacements was designed resulting in the very robust tracking performance. Extensive evaluation shows that the system performs very reliably on sequences that include different types of motion such as walking, sitting, dancing, running and jumping and people of very different body sizes, from a nine year old girl to a tall adult male. 1. Introduction Tracking of the human body, also called motion capture or posture estimation, is a problem of estimating the parameters of the human body model (such as joint angles) from the video data as the position and configuration of the tracked body change over time. -

Photorealistic Scene Reconstruction by Voxel Coloring

In Proc. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conf., pp. 1067-1073, 1997. Photorealistic Scene Reconstruction by Voxel Coloring Steven M. Seitz Charles R. Dyer Department of Computer Sciences University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706 g E-mail: fseitz,dyer @cs.wisc.edu WWW: http://www.cs.wisc.edu/computer-vision Broad Viewpoint Coverage: Reprojections should be Abstract accurate over a large range of target viewpoints. This A novel scene reconstruction technique is presented, requires that the input images are widely distributed different from previous approaches in its ability to cope about the environment with large changes in visibility and its modeling of in- trinsic scene color and texture information. The method The photorealistic scene reconstruction problem, as avoids image correspondence problems by working in a presently formulated, raises a number of unique challenges discretized scene space whose voxels are traversed in a that push the limits of existing reconstruction techniques. fixed visibility ordering. This strategy takes full account Photo integrity requires that the reconstruction be dense of occlusions and allows the input cameras to be far apart and sufficiently accurate to reproduce the original images. and widely distributed about the environment. The algo- This criterion poses a problem for existing feature- and rithm identifies a special set of invariant voxels which to- contour-based techniques that do not provide dense shape gether form a spatial and photometric reconstruction of the estimates. While these techniques can produce texture- scene, fully consistent with the input images. The approach mapped models [1, 3, 4], accuracy is ensured only in places is evaluated with images from both inward- and outward- where features have been detected. -

Online Detector Response Calculations for High-Resolution PET Image Reconstruction

Home Search Collections Journals About Contact us My IOPscience Online detector response calculations for high-resolution PET image reconstruction This article has been downloaded from IOPscience. Please scroll down to see the full text article. 2011 Phys. Med. Biol. 56 4023 (http://iopscience.iop.org/0031-9155/56/13/018) View the table of contents for this issue, or go to the journal homepage for more Download details: IP Address: 171.65.80.217 The article was downloaded on 15/06/2011 at 20:11 Please note that terms and conditions apply. IOP PUBLISHING PHYSICS IN MEDICINE AND BIOLOGY Phys. Med. Biol. 56 (2011) 4023–4040 doi:10.1088/0031-9155/56/13/018 Online detector response calculations for high-resolution PET image reconstruction Guillem Pratx1 and Craig Levin2 1 Department of Radiation Oncology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 2 Departments of Radiology, Physics and Electrical Engineering, and Molecular Imaging Program at Stanford, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA E-mail: [email protected] Received 3 January 2011, in final form 19 May 2011 Published 15 June 2011 Online at stacks.iop.org/PMB/56/4023 Abstract Positron emission tomography systems are best described by a linear shift- varying model. However, image reconstruction often assumes simplified shift- invariant models to the detriment of image quality and quantitative accuracy. We investigated a shift-varying model of the geometrical system response based on an analytical formulation. The model was incorporated within a list- mode, fully 3D iterative reconstruction process in which the system response coefficients are calculated online on a graphics processing unit (GPU). -

Voxel Game Engine Using Blender Game Engine

TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Faculty of Information Technology Department of Computer Science ITV40LT Fred-Eric Kirsi 135216 IAPB VOXEL GAME ENGINE USING BLENDER GAME ENGINE Bachelor's thesis Supervisor: Jaagup Irve Master of Sciences Software Engineer Tallinn 2016 TALLINNA TEHNIKAÜLIKOOL Infotehnoloogia teaduskond Arvutiteaduse instituut ITV40LT Fred-Eric Kirsi 135216 IAPB VOXEL-MÄNGUMOOTOR BLENDER GAME ENGINE ABIL Bakalaureusetöö Juhendaja: Jaagup Irve Magister Tarkvarainsener Tallinn 2016 Author’s declaration of originality I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this thesis. All the used materials, references to the literature and the work of others have been referred to. This thesis has not been presented for examination anywhere else. Author: Fred-Eric Kirsi 23.05.2016 3 Abstract The objective of this thesis is to study various aspects of developing a voxel style game and in the process create a prototype engine to evaluate the possibilities and performance of the algorithms. The algorithms evaluated are Greedy Meshing, A* search, Goal Oriented Action Planning (GOAP), Finite state machine (FSM), and Perlin noise. The used 3d engine is the Bender game engine. The scripting is done in the Python coding language. The result of this work is a working voxel game prototype, where the agents are able to navigate, manipulate, and make decisions in real time. The aim of the prototype is to quantize the performance and feature experience on for the user. The work is divided into four main stages. Firstly evaluation of the work environment and its limitations. Secondly the development and optimization of the voxel implementation. Thirdly the creation and comparison of different pathing implementations. -

Voxel Map for Visual SLAM

This paper has been accepted for publication at the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, 2020. c IEEE Voxel Map for Visual SLAM Manasi Muglikar, Zichao Zhang and Davide Scaramuzza Abstract— In modern visual SLAM systems, it is a stan- Geometry-awareness dard practice to retrieve potential candidate map points from [Newcombe11] overlapping keyframes for further feature matching or direct [Whelan15] Optimal tracking. In this work, we argue that keyframes are not the [Engel14] optimal choice for this task, due to several inherent limitations, Dense representation such as weak geometric reasoning and poor scalability. We propose a voxel-map representation to efficiently retrieve map [Kaess15] This paper points for visual SLAM. In particular, we organize the map [Nardi19] [Rosinol19] points in a regular voxel grid. Visible points from a camera pose Geometric primitives are queried by sampling the camera frustum in a raycasting [Forster17] manner, which can be done in constant time using an efficient [Klein07] [Mur-Artal15] voxel hashing method. Compared with keyframes, the retrieved Sparse keyframes points using our method are geometrically guaranteed to Efficiency fall in the camera field-of-view, and occluded points can be identified and removed to a certain extend. This method also Fig. 1: The optimal SLAM systems should be efficient and have geometrical naturally scales up to large scenes and complicated multi- understanding of the map (denoted by the golden star). Direct methods (red camera configurations. Experimental results show that our dots) associate each keyframe with a semi-dense depth map. They have voxel map representation is as efficient as a keyframe map more scene information but are not efficient. -

Future Graphics in Games

Future graphics in games Anton Kaplanyan Lead researcher Cevat Yerli Crytek CEO Agenda • The history: Crytek GmbH • Current graphics technologies • Stereoscopic rendering • Current graphics challenges • Graphics of the future • Graphics technologies of the future • Server-side rendering • Hardware challenges • Perception-driven graphics The Past - Part 1 • March 2001 till March 2004 • Development of Far Cry • Development of CryEngine 1 • Approach: A naïve, but successful push for contrasts, by insisting on opposites to industry. size, quality, detail, brightness • First right investment into tools - WYSIWYPlay Past - Part 1: CryEngine 1 • Polybump (2001) • NormalMap extraction from High-Res Geometry • First „Per Pixel Shading“ & HDR Engine • For Lights, Shadows & Materials • High Dynamic Range • Long view distances & detailed vistas • Terrain featured unique base-texturing • High quality close ranges • High fidelity physics & AI • It took 3 years, avg 20 R&D Engineers CryENGINE 2 The Past – Part 2 – CryENGINE 2 • April 2004 till November 2007 • Development of Crysis • Development of CryEngine 2 • Approach: Photorealism meets interactivity! • Typically mutual exclusive directions • Realtime productivity with WYSIWYPlay • Extremely challenging, but successful CryEngine 2 - Way to Photorealism The image cannot be displayed. Your computer may not have enough memory to open the image, or the image may have been corrupted. Restart your computer, and then open the file again. If the red x still appears, you may have to delete the image and then insert it again. The Past - Part 2: CryEngine 2 • CGI Quality Lighting & Shading • Life-like characters • Scaleable architecture in • Both content and pipeline • Technologies and assets allow various configurations to be maxed out! • Crysis shipped Nov 2007, works on PCs of 2004 till today and for future.. -

GPU Volume Voxelization Exploration of the Performance Characteristics of Different GPU-Based Implementations

EXAMENSARBETE INOM TEKNIK, GRUNDNIVÅ, 15 HP STOCKHOLM, SVERIGE 2019 GPU Volume Voxelization Exploration of the performance characteristics of different GPU-based implementations GRIGORY GLUKHOV ALEKSANDRA SOLTAN KTH SKOLAN FÖR ELEKTROTEKNIK OCH DATAVETENSKAP GPU Volume Voxelization Exploration of the performance characteris- tics of different GPU-based implementations Aleksandra Soltan Grigory Glukhov Examiner Johan Montelius Supervisor Thomas Sjöland A thesis presented for the degree of Bachelor of Information and Communication Technology KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science SE-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden June 2019 page intentionally left blank 1 Abstract In recent years, voxel-based modelling has seen a reintroduction to computer game development through massive graphics hardware improvements. Never- theless, polygons continue to be the default building block of 3D objects, intro- ducing a need for the transformation of polygon meshes into voxel-based models; this process is known as voxelization. Efficient voxelization algorithms take ad- vantage of the flexibility and control offered by modern, programmable GPU pipelines. However, the variability in possible approaches poses the question of how different GPU-based implementations affect voxelization performance. This thesis explores the impact of GPU-based improvements by comparing four different implementations of a solid voxelization algorithm. The implemen- tations include a naive transition from the CPU to the GPU, a non-branching execution path approach, data pre-processing, and a combination of the two previous approaches. Benchmarking experiments run on four, standard polygo- nal models and three graphics cards (NVIDIA and AMD) provide runtime and memory usage data for each implementation. A comparative analysis is per- formed on the basis of this data to determine the performance impact of the GPU-based adjustments to the voxelization algorithm implementation. -

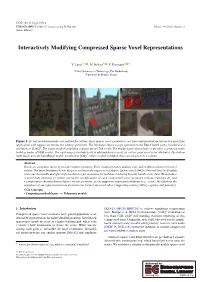

Modifying Compressed Voxel Representations

DOI: 10.1111/cgf.13916 EUROGRAPHICS 2020 / U. Assarsson and D. Panozzo Volume 39 (2020), Number 2 (Guest Editors) Interactively Modifying Compressed Sparse Voxel Representations V. Careil1;2 , M. Billeter1 , E. Eisemann1 y 1Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands 2Université de Rennes, France Figure 1: To test and demonstrate our method for editing large sparse voxel geometries, we have implemented an interactive prototype application with support for interactive editing operations. The left image shows a copy operation in the Epic Citadel scene, voxelized at a resolution of (128k)3. The statue inside this building contains about 170k voxels. The middle image shows larger scale edits, copying an entire building (order of 80M voxels). The right images illustrate tools to add and delete voxels, as well as paint voxel color attributes. The bottom right image uses the San Miguel model, voxelized at (64k)3, where we first solidified, then carved a hole in a column. Abstract Voxels are a popular choice to encode complex geometry. Their regularity makes updates easy and enables random retrieval of values. The main limitation lies in the poor scaling with respect to resolution. Sparse voxel DAGs (Directed Acyclic Graphs) overcome this hurdle and offer high-resolution representations for real-time rendering but only handle static data. We introduce a novel data structure to enable interactive modifications of such compressed voxel geometry without requiring de- and recompression. Besides binary data to encode geometry, it also supports compressed attributes (e.g., color). We illustrate the usefulness of our representation via an interactive large-scale voxel editor (supporting carving, filling, copying, and painting). -

Voxel Size Calibration for High-Resolution CT

10th Conference on Industrial Computed Tomography, Wels, Austria (iCT 2020), www.ict-conference.com/2020 Voxel Size Calibration for High-resolution CT 2 1 Marek Zemek1, Pavel Blažek1, Jan Šrámek , Jakub Šalplachta , Tomáš Zikmund1, Petr Klapetek1,2, Yoshihiro Takeda3, Kazuhiko Omote3, Jozef Kaiser1 1Central European Institute of Technology, Brno University of Technology, Brno, Czech Republic, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2Czech Metrology Institute, Department of Primary Nanometrology and Technical Length, Brno, Czech Republic, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3Rigaku Corporation, 3-9-12, Matsubara-cho, Akishima-shi, Tokyo, 196-8666, Japan, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] http://www.ndt.net/?id=25109 Abstract In cone-beam X-ray computed tomography (CT), distances between the source, object, and detector influence the visual fidelity and voxel size of a reconstructed volume. Calibration using reference objects is an appropriate tool for preventing errors in the estimates of these distances. There is, however, a lack of such objects for high-resolution systems with a small field of view (FoV). In this work, we propose a method to measure the distances mentioned above, improving the determination of voxel size. We use a custom reference object suitable for a FoV of around one millimeter. Many approaches have been developed for this calibration task and discussed in the literature, but none apply to CT scanners with a small FoV and a cone-beam magnification More info about this article: close to one. -

Evaluation of Super-Voxel Methods for Early Video Processing

Evaluation of Super-Voxel Methods for Early Video Processing Chenliang Xu and Jason J. Corso Computer Science and Engineering, SUNY at Buffalo fchenlian,[email protected] Abstract Suite of 3D Supervoxel Segmentations SWA GB GBH Mean Shift Nyström Supervoxel segmentation has strong potential to be in- corporated into early video analysis as superpixel segmen- tation has in image analysis. However, there are many plausible supervoxel methods and little understanding as to when and where each is most appropriate. Indeed, we are not aware of a single comparative study on supervoxel seg- mentation. To that end, we study five supervoxel algorithms in the context of what we consider to be a good supervoxel: namely, spatiotemporal uniformity, object/region boundary detection, region compression and parsimony. For the eval- Benchmark Videos 3D Supervoxel Metrics uation we propose a comprehensive suite of 3D volumetric Figure 1. We comparatively evaluate five supervoxel methods on quality metrics to measure these desirable supervoxel char- 3D volumetric metrics that measure various desirable characteris- acteristics. We use three benchmark video data sets with tics of the supervoxels, e.g., boundary detection. a variety of content-types and varying amounts of human annotations. Our findings have led us to conclusive evi- dence that the hierarchical graph-based and segmentation perpixels have for image analysis. To that end, we perform by weighted aggregation methods perform best and almost a thorough comparative evaluation of five supervoxel meth- equally-well on nearly all the metrics and are the methods ods; note that none of these methods had been proposed of choice given our proposed assumptions. -

Designing a Virtual Reality Game for the Pediatric Patient-Player Experience

Navigating the Pixelated Waters of Voxel Bay: Designing a Virtual Reality Game for the Pediatric Patient-Player Experience Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alice Grishchenko Graduate Program in Design Ohio State University 2017 Thesis Committee: Alan Price Maria Palazzi Jeremy Patterson Copyright by Alice Grishchenko ©2017 All Rights Reserved Abstract Voxel Bay is a virtual reality game created in collaboration with Nationwide Children’s Hospital to distract pediatric hemophilia patients from the anxiety related to the prophylaxis infusion procedure they must undergo regularly. This paper documents answers to the question when designing a game to serve as a pain management distraction technique for pediatric patients, what factors should be considered for the overall experience of the patient-player, clinicians and caregivers, and what may be unique or different from conventional approaches to game development? The answers to the research question are presented in context to the development of Voxel Bay. They are a list of factors to be considered and a documentation of my contribution to the project. The game design concepts discussed include spatial level design for virtual reality and ways to world build without cut scenes. This paper also mentions the hardware configuration used to create an entertaining hands-free system without sacrificing the integrity of the player’s medical experience. After an exploration of these concepts, the paper describes the novel processes used to realize them. The design choices and process documentation are supported by a review of research precedents regarding virtual reality as a distraction tool for medical settings as well as games designed to be used with breathing peripherals, games that use a networked system with different user roles and games that directly inspired the design of Voxel Bay.