A) BULKLEY VALLEY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council of Advisors

Council of Advisors Fraser Region – seven representatives ML (Mary-Lynn) Burke, Leslie Gaudette, Jerry Gosling, Delta; volunteer, Delta Langley; epidemiologist Abbotsford; transit Seniors Planning Team; and retired manager in operator, aiming to help helps seniors navigate B.C.’s Chronic Disease Division, seniors across the province health system for services Public Health Agency of improve their lifestyle and housing; spent 15 Canada; senior analyst, when it comes to housing, years with Vancouver Canadian Cancer Registry, public safety and healthy Coastal Health managing Statistics Canada; eating; and is working to volunteer programs for member Langley Seniors become better informed seniors; vice president on Community Action Table, of senior’s issues and the Delta Housing Be Mine and supporter of Bard in advocate for B.C. residents; Society, creating affordable the Valley and the Langley recipient of the Order of housing for people with Players Drama Club. Abbotsford in recognition varying abilities; columnist of volunteer service and with the Delta Optimist community involvement.. Janet Sie Ling Lee, and the North Delta Burnaby; immigrated to Reporter writing mostly on B.C. from China in 1963; seniors and housing issues. Mohammad Rafiq, hospital nurse for 30 Surrey; volunteer in years; volunteers with community development Vincent Kennedy, senior outreach for the and welfare organizations Langley; retired provincial Collingwood Community including Surrey government employee of Centre; established Seniors Planning Table; 33 years; Deaf and Hard of a Chinese school in seeks to reduce the Hearing Seniors Advocate Vancouver in the 1980s. intergenerational gap with the Western Institute and develop inter-cultural for the Deaf and Hard of communication between Hearing, assisted seniors John Barry Worsfold, between communities. -

Fast Acting Villagers Save Canyon City

~:ov. L~bra~'y. : ..... Department, LVIII, I No. 49 18 Pages Wednesday, June 29, 1966 • 10 Cents o Copy, $3.00 a Year -- Press Run 320~ Council SATURDAY FIRE Highlights - |UNICIPAI. COUNCILLOR L. F. Fast Acting Villagers Bud" French reported Tuesday dght that plans for Terrace's enior Citizens Home have been inalized and that a fund raising Save Canyon City ampalgn will get underway.,in eptember. He.said ~the facliity :~ Fast action by villagers-us!ng~gardenlhoses • was credited ¢ovides 16 daybed ~its and with'Saving the Indian carom'unity 0f.CanyOn City0n the entral block for laundry, 'dining Nass RiVer from burning t0the round early Saturday morning. nd recreational activities. RC~P said the residents were [most fortunate the fire was put fishing or :logging, at the time. out as the village lacks adequate The population of Canyon Ci,ty :OONCl I WAS inforI~ed that firef~ghting equipment. is about 200. [unicipal Administrators now A tugboat and several men from ave the water bylaw under Columbia Cellulose •company's mass tudy and will come up with a River camp raced to the village Dart Gun evised version in the not too which is situated between Kinco. istant future. The new bylaw lith and Greenville. For Doggies lay carry a clause covering A distress call from an uniden- Municipal-,Council .. gave formal ~ater meters so that a regular tiffed Canyon City~ rosident-on- ap~rbval Tuesday night to eading sohedule can be set up. radio-telephone-i'el~b-rted the fire the use of a ~anquilizer dart gun .:. -

Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George

AFFORDABLE HOUSING Choices for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George The Housing Listings is a resource directory of affordable housing in British Columbia and divides British Columbia into 12 zones. Zone 12 identifies affordable housing in the Northern Interior and Prince George. The attached listings are divided into two sections. Section #1: Apply to The Housing Registry Section 1 - Lists developments that The Housing Registry accepts applications for. These developments are either managed by BC Housing, Non-Profit societies, or Co- Operatives. To apply for these developments, please complete an application form which is available from any BC Housing office, or download the form from www.bchousing.org/housing- assistance/rental-housing/subsidized-housing. Section #2: Apply directly to Non-Profit Societies and Housing Co-ops Section 2 - Lists developments managed by non-profit societies or co-operatives which maintain and fill vacancies from their own applicant lists. To apply for these developments, please contact the society or co-op using the information provided under "To Apply". Please note, some non-profits and co-ops close their applicant list if they reach a maximum number of applicants. In order to increase your chances of obtaining housing it is recommended that you apply for several locations at once. Housing for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities, Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George August 2020 AFFORDABLE HOUSING SectionSection 1:1: ApplyApply toto TheThe HousingHousing RegistryRegistry forfor developmentsdevelopments inin thisthis section.section. Apply by calling 250-562-9251 or, from outside Prince George, 1-800-667-1235. -

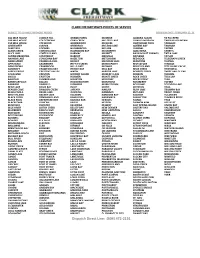

Points of Service

CLARK FREIGHTWAYS POINTS OF SERVICE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE REVISION DATE: FEBRUARY 12, 21 100 MILE HOUSE COBBLE HILL GRAND FORKS MCBRIDE QUADRA ISLAND TA TA CREEK 108 MILE HOUSE COLDSTREAM GRAY CREEK MCLEESE LAKE QUALICUM BEACH TABOUR MOUNTAIN 150 MILE HOUSE COLWOOD GREENWOOD MCGUIRE QUATHIASKI COVE TADANAC AINSWORTH COMOX GRINDROD MCLEOD LAKE QUEENS BAY TAGHUM ALERT BAY COOMBS HAGENSBORG MCLURE QUESNEL TAPPEN ALEXIS CREEK CORDOVA BAY HALFMOON BAY MCMURPHY QUILCHENA TARRY'S ALICE LAKE CORTES ISLAND HARMAC MERRITT RADIUM HOT SPRINGS TATLA LAKE ALPINE MEADOWS COURTENAY HARROP MERVILLE RAYLEIGH TAYLOR ANAHIM LAKE COWICHAN BAY HAZELTON METCHOSIN RED ROCK TELEGRAPH CREEK ANGELMONT CRAIGELLA CHIE HEDLEY MEZIADIN LAKE REDSTONE TELKWA APPLEDALE CRANBERRY HEFFLEY CREEK MIDDLEPOINT REVELSTOKE TERRACE ARMSTRONG CRANBROOK HELLS GATE MIDWAY RIDLEY ISLAND TETE JAUNE CACHE ASHCROFT CRAWFORD BAY HERIOT BAY MILL BAY RISKE CREEK THORNHILL ASPEN GROVE CRESCENT VALLEY HIXON MIRROR LAKE ROBERTS CREEK THREE VALLEY GAP ATHALMER CRESTON HORNBY ISLAND MOBERLY LAKE ROBSON THRUMS AVOLA CROFTON HOSMER MONTE CREEK ROCK CREEK TILLICUM BALFOUR CUMBERLAND HOUSTON MONTNEY ROCKY POINT TLELL BARNHARTVALE DALLAS HUDSONS HOPE MONTROSE ROSEBERRY TOFINO BARRIERE DARFIELD IVERMERE MORICETOWN ROSSLAND TOTOGGA LAKE BEAR LAKE DAVIS BAY ISKUT MOYIE ROYSTON TRAIL BEAVER COVE DAWSON CREEK JAFFARY NAKUSP RUBY LAKE TRIUMPH BAY BELLA COOLA DEASE LAKE JUSKATLA NANAIMO RUTLAND TROUT CREEK BIRCH ISLAND DECKER LAKE KALEDEN NANOOSE BAY SAANICH TULAMEEN BLACK CREEK DENMAN ISLAND -

Telkwa High Road Circle Tour

Telkwa High Road Circle Tour To Prince Rupert (314 km) A Bulkley Valley Museum WITSET D Driftwood Canyon Provincial Park G Spend some time learning about the (MORICETOWN) 10 kilometres north of Smithers human and ancient natural history Known locally as “the Fossil Beds”, Driftwood Canyon is of the Bulkley Valley. Entrance is by the site of the world’s earliest known salmonid fossil— donation. eosalmo driftwoodensis. Since the Bulkley River is one of the B world’s great steelhead rivers, it cannot be a coincidence that Aldermere Trails salmonids got their start in this valley. The fossils at Driftwood An easy trail walk to the site of the Canyon are up to 50 million years old and include plants, insects, Bulkley Valley’s earliest non-First fish, birds and rodents. The land that makes up the park was Nations settlement. donated by long-time Bulkley Valley resident Gordon Harvey. The fossil beds are under the management of BC Parks and C Tyhee Lake Provincial Park visitors are welcome to use this lovely day-use park. There Enjoy the sandy beach, wildlife are picnic tables beside Driftwood Creek. The trail to 17.2 km viewing platform and many amenities the fossil beds is wheelchair accessible. Enjoy the 25.7 km of the park, including playground, firepits, park and the interpretive material, but please do not covered picnic facilities and more. collect fossils. YELLOWHEAD E Babine Mountains Provincial Park Telkwa Access the alpine or stay in the valley — trails N abound in this incredible park. H Paved highway High F Paved road Mountainview Horseback Trail Riding Gravel road Circle route Book a scenic horseback trail ride for an hour or a BULKLEY day. -

Bioenergy in Nakusp and Around BC

Bioenergy in Nakusp and around BC November 22, 2013 David Dubois - Project Coordinator Wood Waste to Rural Heat Project Wood Waste to Rural Heat - Project Goals Work with communities, First Nations and Not-for-Profits assisting them to understand and adopt biomass heating solutions Previously known as the Green Heat Initiative Independent source of Information What does Wood Waste to Rural Heat (WW2RH) do? • Free technical assistance to help determine the best biomass heating solution for the specific application based on the proponents needs. • Developing business cases to help proponents make critical decisions. • Commercial, institutional, and municipal not residential Biomass Heating - Using Wood Chips or Pellets as Fuel Tatla Lake School Enderby District Heating System Baldy Hughes Treatment Centre Biomass District Heat After – Biomass Fired Before – Oil Fired Biomass Heating does not refer to… http://planning.montcopa.org/planning/cwp/fileserver,Path,PLANNING/Admin%20- http://www.thefullwiki.org/Beehive_burner %20Publications/Renewable_Energy_Series/Hydronic_heaters_web.pdf,assetguid,63 e45ed6-2426-4548-bc6dcfb59d457833.pdf How much do I need? Typical Biomass Consumption by Usage 500000 45000 450000 12,000 Truck Loads 40000 1,000 400000 Truck 35000 Loads 350000 30000 300000 25000 250000 20000 5,000 Truck Loads 200000 15000 150000 Tonnes of Biomass per Year Biomass of per Tonnes 10000 100000 20 5000 Truck 50000 Loads 0 0 5 MW Enderby Pellet Plant Power Plant 5MW Community EnderbyCommunity Electricity Electricity Nakusp – Current Energy Costs Unit Fuel Type Sale Retail Price $35.00 size Arena $30.00 kWh Electricity ¢7.4-10.1/kWh ESB $25.00 kWh ¢9.8-10.9/kWh Electricity Public Works $20.00 kWh Electricity ¢8.6-11.0/kWh $15.00 ESB Propane Litres ¢55.3-77.7/l Cost$/GJ Public Works $10.00 Litres Propane ¢57.0-77.9/l Bone $5.00 Hog Fuel/ Dry $5-100/Tonne Wood Chips $- Tonne Pellets Tonne $190-230/tonne (Retail) Nakusp • Current Work High 1) Building inventory review School i. -

Indian and Non-Native Use of the Bulkley River an Historical Perspective

Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians DFO - Library i MPO - Bibliothèque ^''entffique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I IIII III II IIIII II IIIIIIIIII II IIIIIIII 12020070 INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE USE OF THE BULKLEY RIVER AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE by Brendan O'Donnell Native Affairs Division Issue I Policy and Program Planning Ir, E98. F4 ^ ;.;^. 035 ^ no.1 ;^^; D ^^.. c.1 Fisher és Pêches and Oceans et Océans Cariad'â. I I Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians I Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I I INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE I USE OF THE BULKLEY RIVER I AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 1 by Brendan O'Donnell ^ Native Affairs Division Issue I 1 Policy and Program Planning 1 I I I I I E98.F4 035 no. I D c.1 I Fisheries Pêches 1 1*, and Oceans et Océans Canada` INTRODUCTION The following is one of a series of reports onthe historical uses of waterways in New Brunswick and British Columbia. These reports are narrative outlines of how Indian and non-native populations have used these -rivers, with emphasis on navigability, tidal influence, riparian interests, settlement patterns, commercial use and fishing rights. These historical reports were requested by the Interdepartmental Reserve Boundary Review Committee, a body comprising representatives from Indian Affairs and Northern Development [DIAND], Justice, Energy, Mines and Resources [EMR], and chaired by Fisheries and Oceans. The committee is tasked with establishing a government position on reserve boundaries that can assist in determining the area of application of Indian Band fishing by-laws. -

Telkwa Caribou Population Status and Background Information Summary

! ! ! Telkwa Caribou Population Status and Background Information Summary ! ! ! ! June%12,%2014% ! ! ! ! ! ! Prepared!by:! ! Deborah!Cichowski! Caribou!Ecological!Consulting! Box!3652! Smithers,!B.C.! !V0J!2N0! ! ! ! ! ! Prepared!for:! ! BC!Ministry!of!Forests,!Lands!and!Natural!Resource!Operations! Bag!5000! Smithers,!B.C.,!! V0J!2N0! ! ! ! ! ! Acknowledgements ! I!would!like!to!thank!Mark!Williams!and!George!Schultze,!formerly!of!the! BC!Ministry!of!Forests,!Lands!and!Natural!Resource!Operations!(BC! MFLNRO),!for!providing!information!and!for!sharing!their!knowledge!and! perspectives!about!the!Telkwa!caribou!population.!!I!would!also!like!to! thank!Conrad!Thiessen!(BC!MFLNRO)!for!graciously!addressing!all!my! requests!for!information,!and!Conrad!Thiessen!and!Len!Vanderstar!(BC! MFLNRO)!for!sharing!their!knowledge!of!the!Telkwa!caribou!and!recovery! area.!!Conrad!Thiessen!and!Mark!Williams!reviewed!earlier!versions!of! the!report.!!Funding!was!provided!by!BC!Ministry!of!Forests,!Lands!and! Natural!Resource!Operations.! ! ! ! ! ! Telkwa'Caribou'Population'Status'and'Background'Information'Summary' ii' Table of Contents ! Acknowledgements!....................................................................................!ii! Table!of!Contents!.......................................................................................!iii! List!of!Figures!..............................................................................................!v! List!of!Tables!..............................................................................................!vi! -

Iterra HOUSING Tape of Contents

VILLAGEOF TELKWA FeasibiltvStudy Affordable Housing Project for Seniors Village of Telkwa, British Columbia Prepared by: December 2015 iTerra HOUSING Tape of Contents Telkwa: Affordable Housing Feasibility Report Appendix A —- Society] Development Team/Project Support: Society o Telkwa/Society Backgrounder - Canadian Registered Charities page o Society Summary — BC Registry Services - Annual Report 2015 o 2014 Financials - Board List Development Team o Boni MaddisonArchitects - Terra Housing Project Support Letters . Mayor and Council,Village of Telkwa o Midway Service - Telkwa and District Seniors Society Appendix B - Need and Demand: o Affordable Housing Needs Assessment - Telkwa House Wait List Appendix C — Site: Maps o Existing Site Plan - AerialSite Map - Location Maps o Zoning Map Photos Title Documents o Title Searches o Housing Covenant - Lease Agreement - Consent Resolution Memo - Property Assessment Appendix D — Design - Preliminary Plans Appendix E — Financial Model Telkwa Seniors Housing Society Feasibility Report Telkwa Seniors Housing Society (the Society) is a not-for-profit charitable organization that provides housing and other programming to |ow—income seniors in Telkwa BC. The Society operate the Village's only senior housing facility, specifically developed as affordable rental housing for low-income seniors. Telkwa House has enjoyed a high level of success since opening its doors in 2012, with all of its original residents still occupying the 8 units that were built from the Olympic Village storage container housing modules.The Society is now embarking upon planning forthe development of a future facility that mirrors their existing facility in both design and intent. Society and development team documentation is attached as Appendix ”A”. The Need and Demand assessment attached as Appendix”B” identifies a growing need among Te|kwa’s low-income senior population for affordable housing. -

Community Paramedicine Contacts

Community Paramedicine Contacts ** NOTE: As of January 7th, 2019, all patient requests for community paramedicine service should be faxed to 1- 250-953-3119, while outreach requests can be faxed or e-mailed to [email protected]. A centralized coordinator team will work with you and the community to process the service request. For local inquiries, please contract the community paramedic(s) using the station e-mail address identified below.** CP Community CP Station Email Address Alert Bay (Cormorant Island) [email protected] Alexis Creek [email protected] Anahim Lake [email protected] Ashcroft [email protected] Atlin [email protected] Barriere [email protected] Bella Bella [email protected] Bella Coola [email protected] Blue River [email protected] Boston Bar [email protected] Bowen Island [email protected] Burns Lake [email protected] Campbell River* [email protected] Castlegar [email protected] Chase [email protected] Chemainus [email protected] Chetwynd [email protected] Clearwater [email protected] Clinton [email protected] Cortes Island [email protected] Cranbrook* [email protected] Creston [email protected] Dawson Creek [email protected] Dease Lake [email protected] Denman Island (incl. Hornby Island) [email protected] Edgewood [email protected] Elkford [email protected] Field [email protected] Fort Nelson [email protected] Fort St. James [email protected] Fort St. John [email protected] Fraser Lake [email protected] Fruitvale [email protected] Gabriola Island [email protected] Galiano Island [email protected] Ganges (Salt Spring Island)* [email protected] Gold Bridge [email protected] Community paramedics also provide services to neighbouring communities and First Nations in the station’s “catchment” area. -

Mapping in the Tatsi and Zymo Ridge Areas of West-Central British Columbia: Implications for the Origin and History of the Skeena Arch

Mapping in the Tatsi and Zymo ridge areas of west-central British Columbia: Implications for the origin and history of the Skeena arch Joel J. Angen1, a, JoAnne L. Nelson2, Mana Rahimi1, and Craig J.R. Hart1 1 Mineral Deposit Research Unit, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z4 2 British Columbia Geological Survey, Ministry of Energy and Mines, Victoria, BC, V8W 9N3 a corresponding author: [email protected] Recommended citation: Angen, J.J., Nelson, J.L., Rahimi, M., and Hart, C.J.R., 2017. Mapping in the Tatsi and Zymo ridge areas of west- central British Columbia: Implications for the origin and history of the Skeena arch. In: Geological Fieldwork 2016, British Columbia Ministry of Energy and Mines, British Columbia Geological Survey Paper 2017-1, pp. 35-48. Abstract Economically signifi cant porphyry and related mineralization is genetically associated with the Bulkley (Late Cretaceous) and Babine and Nanika intrusive suites (Eocene) in central British Columbia. These intrusions and mineral occurrences are largely restricted to the Skeena arch, a northeast-trending paleohigh that extends transverse to the general trend of Stikine terrane. Elongate intrusions and linear trends of intrusions that suggest emplacement was partially localized along the Skeena arch, and strata of the Skeena Group (Lower Cretaceous) are deformed into northeast trending folds. Stratigraphic relationships across the Skeena arch indicate that it became an arc-transverse paleotopographic high between the Middle Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. The northeast-trending folds, along with the northeasterly orientation of plutonic suites and the Skeena arch as a whole, are thought to be manifestations of a fundamental arc-transverse structural anisotropy. -

DMO= Destination Marketing Organisation)

BACKGROUNDER A Destination BC Co-op Marketing Partnerships Program 2017/18 Participating Communities (*DMO= Destination Marketing Organisation) Consortium Region Approved DBC Funding Gold Rush Circle Route (CRD Electoral Area C, CRD Electoral Area F, District of Wells, Cariboo Chilcotin $16,000 Likely & District Chamber of Commerce, Coast Barkerville Historic Town) Great Bear Project (Tourism Prince Rupert, Bella Coola Valley Tourism, West Chilcotin Cariboo Chilcotin $68,800 Tourism Association) Coast Cariboo Calling (City of Williams Lake, City of Quesnel, Cariboo Regional District, 100 Mile Cariboo Chilcotin $18,936 House, Williams Lake Indian Band, X’atsull Coast (Soda Creek) Indian Band) Gold Rush Trail (Barkerville, Wells, Quesnel, Xat’sull, Williams Lake, Cariboo Regional Cariboo Chilcotin $40,000 District (multiple electoral areas), 100 Mile Coast and Vancouver, House, Clinton, Lillooet, Bridge River Valley Coast and Mountains (SLRD Area A), Yale, Hope, Abbotsford, New Westminster) MyKootenays (Tourism Fernie, Cranbrook Tourism, Tourism Kimberley, Invermere Kootenay Rockies $20,000 Panorama DMO, Tourism Radium, Regional District of East Kootenay, Elk Valley Cultural Consortium (Arts Council, Museum, Heritage Sites, Fernie & Sparwood Chambers, District of Elkford) Columbia Valley (Invermere Panorama DMO, Fairmont Business Association, Tourism Kootenay Rockies $85,000 Radium Hot Springs Columbia Valley Golf Association, Copper Point Resort, Fairmont Creek Property Rentals, Bighorn Meadows Resort, The Residences at Fairmont Ridge)