The Enigma Machine: Unravelling the Domestic Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dada Surrealism and Expressionism

• Dada was an art movement formed during the First World War in Zurich in 1916 in negative reaction to the horrors and folly of the war. The art, poetry and performance produced by Dada artists is often satirical and nonsensical in nature. Dada artists felt war called into question every aspect of society and their aim was to destroy all traditional values and assumptions. Dada was also anti-bourgeois and aligned with the radical left. The founder of Dada was a writer, Hugo Ball and in 1916 he started a satirical night-club in Zurich, the Cabaret Voltaire. Dada became an international movement and was the basis of Surrealism in Paris after the war. Leading artists associated with it include Jean Arp (1886-1966), Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), Francis Picabia (1879-1953) and Kurt Schwitters (1887- 1948). Duchamp’s questioning of the fundamentals of Western art had a profound subsequent influence. • Surrealism was founded by French poet André Breton in Paris in 1924 and it became an international movement including British Surrealism which formed in 1936. Surrealists were strongly influenced by Sigmund Freud (the founder of psychoanalysis) and his theories about the unconscious and the aim of the movement was to reveal the unconscious and reconcile it with rational life. Key artists involved in the movement were Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, René Magritte and Joan Miró. Two broad types of surrealism can be seen: one based on dreamlike imagery and the other on automatism (a process of making which unleashed the unconscious by drawing or writing without conscious thought). Some (such as Max Ernst) used new techniques such as frottage and collage to create unusual imagery. -

Rise of Modernism

AP History of Art Unit Ten: RISE OF MODERNISM Prepared by: D. Darracott Plano West Senior High School 1 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES IMPRESSIONISM Edouard Manet. Luncheon on the Grass, 1863, oil on canvas Edouard Manet shocking display of Realism rejection of academic principles development of the avant garde at the Salon des Refuses inclusion of a still life a “vulgar” nude for the bourgeois public Edouard Manet. Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas Victorine Meurent Manet’s ties to tradition attributes of a prostitute Emile Zola a servant with flowers strong, emphatic outlines Manet’s use of black Edouard Manet. Bar at the Folies Bergere, 1882, oil on canvas a barmaid named Suzon Gaston Latouche Folies Bergere love of illusion and reflections champagne and beer Gustave Caillebotte. A Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas Gustave Caillebotte great avenues of a modern Paris 2 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES informal and asymmetrical composition with cropped figures Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas Edgar Degas admiration for Ingres cold, austere atmosphere beheaded dog vertical line as a physical and psychological division Edgar Degas. Rehearsal in the Foyer of the Opera, 1872, oil on canvas Degas’ fascination with the ballet use of empty (negative) space informal poses along diagonal lines influence of Japanese woodblock prints strong verticals of the architecture and the dancing master chair in the foreground Edgar Degas. The Morning Bath, c. 1883, pastel on paper advantages of pastels voyeurism Mary Cassatt. The Bath, c. 1892, oil on canvas Mary Cassatt mother and child in flattened space genre scene lacking sentimentality 3 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES Claude Monet. -

The Interwar Years,1930S

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • My sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN • The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1880 • Late Victorians, 1880-1900 • The Edwardians, 1890-1910 • The Great War and After, 1910-1930 • The Interwar Years, 1930s • World War II and After, 1940-1960 • Pop Art & Beyond, 1960-1980 • Postmodern Art, 1980-2000 • The Turner Prize • Summary West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

OOT 2020 Packet 5.Pdf

OOT 2020: [The Search for a Middle Clue] Written and edited by George Charlson, Nick Clanchy, Oli Clarke, Laura Cooper, Daniel Dalland, Alexander Gunasekera, Alexander Hardwick, Claire Jones, Elisabeth Le Maistre, Matthew Lloyd, Lalit Maharjan, Alexander Peplow, Barney Pite, Jacob Robertson, Siân Round, Jeremy Sontchi, and Leonie Woodland. THE ANSWER TO THE LAST TOSS-UP SHOULD HAVE BEEN: Song dynasty Packet 5 Toss-ups: 1. This book argues that ‘changes of diet are more important than changes of dynasty or even of religion’ and wondered why statues commemorate politicians rather than bacon-curers and cooks. This book’s publisher, Victor Gollancz [guh-LANTS], added a foreword objecting that its author ‘does not once define what he means by’ a certain political movement, referring to the second of this book’s two parts. This book opens with a portrayal of the relatively wealthy Booker family, while subsequent chapters discuss the poor housing and working conditions of coal miners. Taking its title from a jokingly-named ‘tumble-down’ structure on a ‘muddy little canal’ in the North, for 10 points, name this sociological and political essay by George Orwell. ANSWER: The Road to Wigan Pier <AH> 2. Whittaker et al devised a namesake immaturity speciation pulse model to describe evolution in these ecosystems. Losos and colleagues found that Anolis ecomorphs, including the crown-giant and trunk-ground, have evolved convergently in these ecosystems. A study on hydraulic failure in Argyranthemum suggests that the tendency for plants to evolve woodiness in these ecosystems is an adaptation to drought resistance. Species area curves were devised by MacArthur and Wilson as part of their theory of the biogeography of these places. -

Artknows Transforming Yourself and the World You Live in Through Art

CTA/Durland Alternatives Library Non-Profit Organization 127 Anabel Taylor Hall U.S. Postage Paid Ithaca, NY 14853 Permit 448 www.prisonerexpress.org Ithaca, NY 14850 Change Service Requested ArtKnows Transforming yourself and the world you live in through art. A Prisoner Express publication exploring the world of art. Diary of Discoveries by Vladimir Kush, famous Surrealist artist www.prisonerexpress.com Dear Art Program Participants, I hope you enjoy this newest edition of Treacy’s ArtKnows column. Her exploration of figurative sculpture is a great introduction into the mind of an artist. I encourage you to read it more than once as, I found many of the ideas she shares deep and require much thought and attention for me to grasp. There is a second section to this art packet put together by Danielle, a new PE volunteer. She explores the world of Surrealism, and offers a number of drawing instruction in this genre. Please note Danielle is asking for your art submissions using some of the drawing techniques she shares. We will be having a public art show in Spring 17 and your art submissions will be considered for exhibition for the PE Art Show on the Cornell Campus. Please send us feedback on the packets— both Treacy and Danielle are interested in hearing your reactions to their contribution to this mailing. We at PE wish you a happy holiday. Even though you may be isolated, you are not alone and we wish you the very best. Figurative Sculpture Whenever an artist starts something new – either a new particular work of art or an entirely new medium, it’s not uncommon to want to talk about it. -

Introduction to Surrealism 2/8/16 Terms

Introduction to Surrealism 2/8/16 Terms “equivocation”, a term coined by Dennis Hollier in the 1930s to describe a technique that takes the form of mimesis; it appropriates the enemy’s slogans and tactics by identifying with the aggressor. (p. 54) “epistemologically ambiguous” Heterology: exposing difference as the rupture of unity. post-structuralism / deconstruction: concerns the construction (or deconstruction) of the ways that texts make meaning. Predicated on reading culture as a system of signs. Bourdieu’s Food Space (updated) Manet’s “The Balcony” (1868) Art, and certainly documentary, is always an expression of its technological conditions. It’s both the call and the response. ● modern newspaper ~1850’s ● photography ~1840’s ● cinema 1890’s / 1920’s ● commercial radio 1920’s ● In the 1880’s Psychology invents the words “solipsism” and “telepathy”. ● In the 1920’s term Mass media is used for the first time, ○ Only after invention of term “mass media” does “communication” come to refer to face-to-face engagement as well, with little distinction between face-to-face and at a distance. early “attention” economy T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” (1922) Failure of communication rendered as sexual failure. —Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden, Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither Living nor dead, and I knew nothing, Looking into the heart of light, the silence. (lines 37-41) I have heard the key Turn in the door once and turn once only We think of the key, each in his prison Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison. -

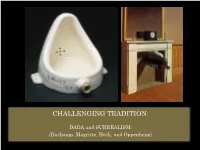

DADA and SURREALISM: (Duchamp, Magritte, Höch, and Oppenheim) ARTISTS ASSOCIATED with the DADA MOVEMENT

CHALLENGING TRADITION: DADA and SURREALISM: (Duchamp, Magritte, Höch, and Oppenheim) ARTISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE DADA MOVEMENT Online Links: Marcel Duchamp - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Readymades of Marcel Duchamp - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Nihilism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Armory Show - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Duchamp and Readymades – Smarthistory Duchamp's Fountain – Smarthistory Duchamp's In Advance of a Broken Arm – Smarthistory Jean Arp's Untitled – Smarthistory Hoch's Kitchen Knife - Smarthistory ARTISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE DADA MOVEMENT Online Links: Hannah Höch - Wikipedia Hannah Hoch - Whitechapel Gallery exhibition (with video) Hannah Hoch Art Punk Whitechapel - The Guardian Hannah Hoch and Photomontage - Video made by MOMA Schwitter's Merz Picture – Smarthistory Kurt Schwitters Ursonate - Dada Video on YouTube 1928 Dadaist Film by Director Hans Richter - YouTube MAX ERNST Online Links: Max Ernst - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Surrealism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia André Breton - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Ernst's Two Children Threatened by a Nightingale – MOMA Modern Art: Max Ernst - YouTube RENE MAGRITTE Online Links: René Magritte - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Review/Art - Magritte And His Defiance Of Life - Review - NYTimes.com ART - ART - Surreal Hero for a Nation of Contradictions - Biography - NYTimes.com Magritte Treacher of Images – Smarthistory Rene Magritte Documentary - YouTube In February of 1913, the Armory of the Sixty- ninth Regiment, National Guard, on Lexington Avenue at 25th Street in New York was the site of an international exhibition of modern art. A total of 1,200 exhibits, including works by Post-Impressionists, Fauves, and Cubists, as well as by American artists, filled eighteen rooms. -

Transmutational Harmony

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2011 Transmutational Harmony Jonathan Mayers University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Mayers, Jonathan, "Transmutational Harmony" (2011). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1328. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1328 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transmutational Harmony A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Fine Arts by Jonathan Joseph Mayers B.F.A. Louisiana State University, 2007 May, 2011 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my loving parents, Hans and Sharron Mayers, my sister, Jennifer Mayers, my paternal grandparents, Jerome and Gladys Spinato, and my maternal grandparents, Clyde and Gertrude Brown. My family has always encouraged me to pursue my art and I remain very grateful for their support. -

1 Avant-Garde and Avant-Gardes

1 Avant-garde and avant-gardes 2 ART INQUIRY3 RECHERCHES SUR LES ARTS Volume XIX (XXVIII) A v a n t - g a r d e a n d a v a n t - g a r d e s Ł ó d ź 2 0 1 7 4 ART INQUIRY Recherches sur les arts Volume XIX (XXVIII) Avant-garde and avant-gardes Łódzkie Towarzystwo Naukowe / Societas Scientiarum Lodziensis 90-505 Łódź, ul. M. Skłodowskiej-Curie 11, tel. (+48 42) 665 54 59 fax (+48 42) 665 54 64 Sales office (+48 42) 665 54 48, http://sklep.ltn.lodz.pl, www.ltn.lodz.pl, e-mail: [email protected] Editorial board of ŁTN: Krystyna Czyżewska, Edward Karasiński, Wanda M. Krajewska (Editor-in-Chief), Henryk C. Piekarski, Jan Szymczak Editorial board: Roy Ascott, Sean Cubitt, Bohdan Dziemidok, Erkki Huhtamo, Ryszard Hunger, Krystyna Juszyńska, Małgorzata Leyko, Robert C. Morgan, Wanda Nowakowska (chair), Ewelina Nurczyńska-Fidelska, Krystyna Wilkoszewska, Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska Editor-in-Chief: Grzegorz Sztabiński Editors: Andrzej Bartczak, Ryszard W. Kluszczyński, Krzysztof Stefański Editors of the volume: Grzegorz Sztabiński, Paulina Sztabińska Language Editors: Alina Kwiatkowska, Andrew Tomlinson Editorial Associate: Paulina Sztabińska Reviewer: Roman Kubicki Cover: Grzegorz Laszuk Graphic design: Tomasz Budziarek Edited with the financial support of the Strzemiński Academy of Arts in Łódź, and the Faculty of Philosophy and History, University of Łódź Indexed by SCOPUS, CEEOL, EBSCOhost, CEJSH, ERIH Plus, Index Copernicus, Ministry of Science and Higher Education, ProQuest, POL-index. Full- text articles are available online at www.ceeol.com, www.cejsh.icm.edu.pl, Index Copernicus, SCOPUS, EBSCOhost, ProQuest and www.ibuk.pl. -

Inter/Cultural Encounters of Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington

PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH DJILLALI LIABES UNIVERSITY OF SIDI BEL ABBES FACULTY OF LETTERS LANGUAGES AND ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Myths and Metamorphoses in Dorothea Tanning and Leonora jh Carrington’s Art Thesis Submitted to the Department of English in Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctorat in Comparative Literature Presented by: Supervised by: Miss Nadia HAMIMED Prof. Fewzia BEDJAOUI BOARD OF EXAMINERS: President: Dr. Belkacem BENSEDDIK DLU, Sidi Bel Abbes Supervisor: Prof. Fewzia BEDJAOUI DLU, Sidi Bel Abbes Examiner: Prof. Faiza SENOUCI University of Tlemcen Examiner: Prof. Bakhta ABDELHAY University of Mostaghanem Examiner: Dr. Djamel BENADLA University of Saida Examiner: Dr. Mohamed GRAZIB University of Saida Academic year: 2019 - 2020 DEDICATIONS Most importantly, none of this would have been possible without the love and patience of my parents. My family to whom this thesis is dedicated, has been a constant source of love, concern, support and strength all these years. I would like to express my heart-felt gratitude to my mother Khadidja, a very special thank you for providing love and attention through the months of writing. And also for the myriad of ways in which, throughout my life, you have actively supported me in my determination to find and realise my potential, and to make this contribution to our world. I am grateful to my dear father Farouk who taught me that the best kind of knowledge to have is that which is learned for its own sake. He has been nicely my supporter until my research was fully finished. -

Fine Arts Session- 2021-22

FACULTY OF PERFORMING ARTS AND VISUAL ARTS SYLLABUS Of Bachelor of Arts Semester: I-VI (Under Continuous Evaluation System) Session: 2021-22 The Heritage Institution KANYA MAHA VIDYALAYA JALANDHAR FACULTY OF ARTS (Autonomous) Programme Specific Outcome The student can get the following benefits after the studying Fine Arts (Drawing & Painting) as one of the subjects in B.A : P.S.O (1) The course will polish the talent of Students at initial level. P.S.O (2) The knowledge of theory of Art, which includes Pre- Historic to Modern age, enables them to be aware of what has happened in the field of Art. P.S.O (3) There will be a development in Practical aspect of Drawing& Painting at basic level. P.S.O (4) Introduction to the commercial aspects of the programme. P.S.O (5) Knowledge of entrepreneurship in the field of Art at initial level. Scheme of Studies and Examination for three years degree programme Bachelor of Arts SEMESTER-I Session (2021-22) Bachelor of Arts SEMESTER-I Examination Marks time Course Programme Course type (in Hours) name Code Course Title Ext. Total CA L P Fine arts: BARM- (Drawing and 40 - 3 Painting) 1245 (Theory) Bachelor BARM- Fine arts: - 20 5 of Arts 1245 (P) Still Life E 100 20 (I) (Drawing ) (Practical) BARM- Fine arts: - 20 5 1245(P) Letter Writing (II) (Practical) E- Elective Scheme of Studies and Examination for three years degree programme Bachelor of Arts SEMESTER-II Session (2021-22) Bachelor of Arts SEMESTER-II Examination Marks time Course Programme Course type (in Hours) name Code Course Title Ext. -

Important Art Movements to Remember

Important Art Movements To Remember What is an Art Movement ? Art Movements are the collective titles that are given to artworks which share the same artistic ideals, style, technical approach or timeframe. There is no fixed rule that determines what constitutes an art movement. The artists associated with one movement may adhere to strict guiding principles, whereas those who belong to another may have little in common. Art Movements are simply a historical convenience for grouping together artists of a certain period or style so that they may be understood within a specific context. Art Movements are usually named retrospectively by art critics or historians and their titles are often witty or sarcastic nicknames pulled from a bad review. Grouping artists of similar interests or styles into Art Movements is mainly a characteristic of Western Art. Art Movements are essentially a 20th century development when there was a greater variety of styles than at any other period in the history of art. 20th century 1900–1921 Wassily Kandinsky, 1903, Der Blaue Reiter 21.1 cm × 54.6 cm (8.3 in × 21.5 in) Bauhaus Institute of Creative Sciences, Chittaranjan Park, New Delhi, 9818541252 Page 1 Important Art Movements To Remember Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, 1905, Picasso's Rose Period Henri Matisse 1905, Fauvism Pablo Picasso 1907, Proto-Cubism Georges Braque 1910, Analytic Cubism Institute of Creative Sciences, Chittaranjan Park, New Delhi, 9818541252 Page 2 Important Art Movements To Remember Kazimir Malevich, (Supremus No. 58), Museum