Introduction to Rifle Platoon Operations B3j3638

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

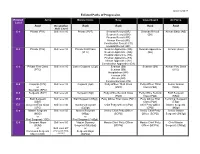

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

Lee D. Bonar Jr. / Hope for the Warriors / Director of Military Relations

Lee D. Bonar Jr. / Hope For The Warriors / Director Of Military Relations Sergeant Major Lee D. Bonar Jr. was born 13 July 1960. He enlisted in the Marine Corps on 15 January 1985 at Wheeling, West Virginia and completed recruit training at MCRD Parris Island, South Carolina, 18 April 1985. Sergeant Major Bonar has served in a variety of units and billets throughout his career. Upon graduation from boot camp he was meritoriously promoted to Lance Corporal and reported to Infantry Training School, Camp Geiger, North Carolina, where he attained the MOS 0341 /Mortar man. In July of 1985 he reported to Sea School, MCRD San Diego, California where upon graduating was assigned to the Aircraft Carrier USS Carl Vinson, CVN-70, docked in Alameda, California. His tour on Sea Duty ended on 2 August 1987 and he had been promoted to Corporal and graduated from NCO school. In September 1987 Corporal Bonar reported to 3rd Light Armored Vehicle Battalion, 29 Palms, California. Corporal Bonar became a Forward Observer and was promoted to Sergeant. On 1 December 1988, Sergeant Bonar reported to Rifle Security Company, Windward Barracks, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Sergeant Bonar held the billet of Platoon Sergeant for the guard force and weapons platoon. Upon completing his tour on Barracks Duty Sergeant Bonar reported to the Naval Drug and Alcohol Counseling School, Naval Station, San Diego, California, on 12 January 1989. On 12 April 1989 Sergeant Bonar was assigned to the Naval Drug and Alcohol Rehabilitation Center, NAS Miramar, California. Sergeant Bonar conducted inpatient counseling and was assigned as an Instructor at the Naval Drug and Alcohol Counseling School in April 1992. -

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure This publication is an extract mostly from FM 3-21.8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad, but it also includes references from other FMs. It provides the tactical standing operating procedures for infantry platoons and squads and is tailored for ROTC cadet use. The procedures apply unless a leader makes a decision to deviate from them based on the factors of METT-TC. In such a case, the exception applies only to the particular situation for which the leader made the decision. CHAPTER 1 - DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................... 2 CHAPTER 2 - COMMAND AND CONTROL.............................................................. 7 SECTION I – TROOP LEADING PROCEDURES ................................................. 7 SECTION II – RISK MANAGEMENT ................................................................... 10 SECTION III - ORDERS ........................................................................................... 12 CHAPTER 3 – OPERATIONS...................................................................................... 15 SECTION I – FIRE CONTROL AND DISTRIBUTION ....................................... 15 SECTION II – RANGE CARDS AND SECTOR SKETCHES.............................. 17 SECTION III - MOVEMENT ................................................................................... 24 SECTION IV - COMMUNICATION ....................................................................... 26 SECTION V - REPORTS ......................................................................................... -

US Military Ranks and Units

US Military Ranks and Units Modern US Military Ranks The table shows current ranks in the US military service branches, but they can serve as a fair guide throughout the twentieth century. Ranks in foreign military services may vary significantly, even when the same names are used. Many European countries use the rank Field Marshal, for example, which is not used in the United States. Pay Army Air Force Marines Navy and Coast Guard Scale Commissioned Officers General of the ** General of the Air Force Fleet Admiral Army Chief of Naval Operations Army Chief of Commandant of the Air Force Chief of Staff Staff Marine Corps O-10 Commandant of the Coast General Guard General General Admiral O-9 Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Rear Admiral O-8 Major General Major General Major General (Upper Half) Rear Admiral O-7 Brigadier General Brigadier General Brigadier General (Commodore) O-6 Colonel Colonel Colonel Captain O-5 Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Commander O-4 Major Major Major Lieutenant Commander O-3 Captain Captain Captain Lieutenant O-2 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant Lieutenant, Junior Grade O-1 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant Ensign Warrant Officers Master Warrant W-5 Chief Warrant Officer 5 Master Warrant Officer Officer 5 W-4 Warrant Officer 4 Chief Warrant Officer 4 Warrant Officer 4 W-3 Warrant Officer 3 Chief Warrant Officer 3 Warrant Officer 3 W-2 Warrant Officer 2 Chief Warrant Officer 2 Warrant Officer 2 W-1 Warrant Officer 1 Warrant Officer Warrant Officer 1 Blank indicates there is no rank at that pay grade. -

Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad

FM 7-8 Table of Contents RDL Document Download Homepage Information Instructions *FM 7-8 FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS NO. 7-8 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 22 April 1992 FM 7-8 INFANTRY RIFLE PLATOON AND SQUAD IMPORTANT U.S. Army Infantry School Statement on U.S. NATIONAL POLICY CONCERNING ANTIPERSONNEL LAND MINES Table of Contents CHANGE 1 Preface http://www.adtdl.army.mil/cgi-bin/atdl.dll/fm/7-8/toc.htm (1 of 10) [1/9/2002 9:34:30 AM] FM 7-8 Table of Contents Chapter 1 - DOCTRINE Section I - Fundamentals 1-1. Mission 1-2. Combat Power 1-3. Leader Skills 1-4. Soldier Skills 1-5. Training Section II - Platoon Operations 1-6. Movement 1-7. Offense 1-8. Defense 1-9. Security Chapter 2 - OPERATIONS Section I - Command and Control 2-1. Mission Tactics 2-2. Troop-Leading Procedure 2-3. Operation Order Format Section II - Security 2-4. Security During Movement http://www.adtdl.army.mil/cgi-bin/atdl.dll/fm/7-8/toc.htm (2 of 10) [1/9/2002 9:34:30 AM] FM 7-8 Table of Contents 2-5. Security in the Offense 2-6. Security in the Defense Section III - Movement 2-7. Fire Team Formations 2-8. Squad Formations 2-9. Platoon Formations 2-10. Movement Techniques 2-11. Actions at Danger Areas Section IV - Offense 2-12. Movement to Contact 2-13. Deliberate Attack 2-14. Attacks During Limited Visibility Section V - Defense 2-15. Conduct of the Defense 2-16. Security 2-17. -

Military Units Style Contents

Military Units Style - Colors Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Blue Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 1 Military Units Style - Fill Symbols Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 2 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols à Infantry Soldier  Helicopter - AH Apache Å Missile Launcher Æ Frigate Ê Generic Tank Ç Destroyer Ë Enemy Tank È Submarine SSBN Ì B-2 Stealth É Submarine Attack Ó F-14 Tomcat À Torpedo Ô Fighter ß Explosion Õ FA-18 ! Unit Ö F-5 " Headquarters Unit Ù Fighter # Logistics/Admin Installation Ú Fighter $ Theater Ü Generic Fighter % Corps Ò E-3 AWACS & Supply unit Ï Helicopter - CH-46 Chinook ' Squad Ð Helicopter - AH Cobra ( Section/Platoon Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 3 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols ) Platoon/Squadron 8 Infantry Battalion * Company/Battery/Troop 9 Infantry Regiment + Battalion/Squadron : Infantry Brigade , Regiment ; Infantry Division - Brigade < Infantry Corps . Division = Infantry Army / Corps > Infantry Mechanized Squad 0 Army ? Infantry Mechanized Section 1 Infantry @ Infantry Mechanized Platoon 2 Infantry Mechanized A Infantry Mechanized Company 3 Armor B Infantry Mechanized Battalion Company 4 Infantry Squad C Infantry Mechanized Regiment 5 Infantry Section D Infantry Mechanized Brigade 6 Infantry Platoon E Infantry Mechanized Division 7 Infantry Company F Infantry Mechanized Corps Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. -

Veteran's Day Parade

D6 The Dispatch and The Rock Island Argus Wednesday, November 11, 2015 Jose S. Maldonado Kenneth L. Carlson Merwin P. Baker Jeremy E. King Kevin M. Gladkin Naval Aircrewman First Class/ Richard L. Geisler Specialst Fourth Class Gunnery Sergeant Sergeant Aviation Warfare U.S. Army U.S. Army Third Class U.S. Marine Corps U.S. Marine Corps U.S. Navy Served in Germany 1962-1964 Radio Operator Posted at Navy Station Great Lakes Stationed in Germany U.S. Navy Tameka Brand George Weckel Anthony Villarreal Congresswoman Tammy Scott R. Johnson Corporal Duckworth Laura Nichols Technical Sergeant Specialist Sergeant Major U.S. Air Force U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Major U.S. Army Bronze Star of Valor U.S. Army Stationed in Florida Vietnam, 1966-1968 National Guard U.S. Air Force Very proud of you! God Bless! Afghanistan Served in Iraq Retired Anthony Pompa Tony Pompa Eric Lohmeier Brett Lohmeier Fred Rodts Jeffry Rodts Sergeant Sergeant Specialist Specialist Lance Corporal U.S. Army Air Corps U. S. Army U.S. Army Former Army Ranger U.S. Army U.S. Marine Corps Killed in action Served in Korea 3rd Infantry Division U.S. Army Vietnam, 1969-1971 Desert Storm, Somalia European Theater 1944 Iraq & Afghanistan 2002 - 2008 2002-2005 Purple Heart 1990-1994 Ronald R. Nelson Andrew Lawrence Greer Polly Haskins Jacob William Scott Sanford (Sandy) Bray, Jr Master Sergeant Marvin E. Wichman Corporal Commander Private First Class U.S. Marine Corps “Hoorah” Private First Class U.S. Marine Corps U.S. Marine Corps U.S. Navy Korea & Vietnam, 1949-1970 U.S. -

Unit-Manning in the Us Army

FORGING THE SWORD: UNIT- MANNING IN THE US ARMY Pat Towell FORGING THE SWORD: UNIT-MANNING IN THE US ARMY by Pat Towell Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments September 2004 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) is an independent, nonprofit, public policy research institute established to make clear the inextricable link between near-term and long- range military planning and defense investment strategies. The Center is directed by Dr. Andrew F. Krepinevich and funded by foundations, corporations, government, and individual grants and contributions. This report is one in a series of CSBA analyses on future US military strategy, force structure, operations, and budgets. The author would like to thank the staff of the CSBA for their comments and assistance on this report: Steven Kosiak, Andrew Krepinevich, Christopher Sullivan, Luciana Turner, Michael Vickers, and Barry Watts. He also greatly appreciates comments by John Chapla, Lt. Gen. Robert W. Elton (US Army ret.), Robert Goldich, W. Michael Hix, Maj. Brendan B. McBreen (USMC), Robert S. Rush, Johnathan Shay, Guy L. Siebold, and Col. Paul D. Thornton (US Army), each of whom generously took time to review earlier drafts of the report. The analysis and findings presented here are solely the responsibility of CSBA and the author. 1730 Rhode Island Ave., NW Suite 912 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 331-7990 CONTENTS OVERVIEW................................................................ I CHAPTER 1. THE QUEST FOR STABILIZATION ..................1 The Current System...........................................4 The Road to COHORT.........................................7 Beyond the Cold War.........................................9 How Certain a Future?.....................................12 One More Time................................................15 CHAPTER 2. -

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure This publication is an extract mostly from FM 3-21.8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad , but it also includes references from other FMs. It provides the tactical standing operating procedures for infantry platoons and squads and is tailored for ROTC cadet use. The procedures apply unless a leader makes a decision to deviate from them based on the factors of METT-TC. In such a case, the exception applies only to the particular situation for which the leader made the decision. CHAPTER 1 - DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................... 2 CHAPTER 2 - COMMAND AND CONTROL.............................................................. 6 SECTION I – TROOP LEADING PROCEDURES .................................................. 6 SECTION II – RISK MANAGEMENT ..................................................................... 9 SECTION III - ORDERS ........................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 3 – OPERATIONS ..................................................................................... 14 SECTION I – FIRE CONTROL AND DISTRIBUTION ....................................... 14 SECTION II – RANGE CARDS AND SECTOR SKETCHES ............................. 16 SECTION III - MOVEMENT ................................................................................... 25 SECTION IV - COMMUNICATION ....................................................................... 27 SECTION V - REPORTS ......................................................................................... -

Headquarters and Headquarters Company Infantry Division Battle Group

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS AND HEADQUARTERS COMPANY INFANTRY DIVISION BATTLE GROUP HEADQUART'ERS, DEPARTMENT OF -THE ARMY FEBRUARY 1960 4115B *FM 7-21 FIELD MANUAL) HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY No. 7-21 WASHINGTON 25, D. C., 26 February 1960 HEADQUARTERS AND HEADQUARTERS COMPANY INFANTRY DIVISION BATTLE GROUP Paragraph Page CH aPTER1. GENERAL Section I. Mission and organization ------------------------- 1-3 2 II. Company headquarters -------------------------- 4, 5 2 III. Battle group headquarters section --------------- 6-11 4 CHAPTER 2. COMMUNICATION PLATOON Section I. General ------------------------------ - 12-33 6 II. Command posts --------------------------------- 34-41 26 III. Tactical employment --------------------------- 42-50 31 CHAPTER 3. SUPPLY AND MAINTENANCE PLATOON Section I. Mission, organization, duties and installations ------ 51-56 40 II. Combat supply operations -----------------------_ 57-65 45 ILI. Maintenance ---------------------------------- 66-71 55 IV. Repair, salvage, and miscellaneous activities -------- 72-78 57 CHPTER 4. ENGINEER PLATOON Section I. General -------------------------------- 79-83 60 II. Employment ----------------------------------- 84-87 62 CHAPTER 5. MEDICAL PLATOON ------------------------- 88-92 64 6. PERSONNEL SECTION ----------------------- 93, 94 68 APPENDix REFERENCES----------------- ---------------- 69 INDEX -------------.--.------------------- ---------- ----- 71 * This manual supersedes FM 7-21, 8 August 1957; FM 7-25, 21 August 1950, including C 1, 22 October 1951; C 2, 25 September 1952; C 3, 15 December 1952; and C 4, 27 August 1953; and FM 7-30, 21 April 1954. TAGO 4118B-February 1 CHAPTER 1 GENERAL Section I. MISSION AND ORGANIZATION 1. Purpose and Scope a. This text is a guide to the training and tactical employment of the headquarters and headquarters company of the battle group. It covers the organization and operations of the company and its elements. -

Sergeant Major Kent Bids MCRD Farewell by Lance Cpl

MARINE CORPS RECRUIT DEPOT SAN DIEGO New DIs graduate Rumble in Hawaii’s jungle p. 6 p. 3 AND THE WESTERN RECRUITING REGION Vol. 71 – Issue 12 “Where Marines Are Made” FRIDAY, MAY 6, 2011 Sergeant Major Kent bids MCRD farewell by Lance Cpl. Eric instructors in attendance. Quintanilla “(They) have truly earned the Chevron staff title. It is amazing what you have done to make these Marines,” he Sergeant Major Carlton W. added. Kent spoke with Marines and During his speech, the sergeant recruits April 27 at Shepherd’s major addressed topics such as Field aboard Marine Corps the value of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego for the in today’s world and discussed last time as the sergeant major of opportunities available to the Marine Corps. Marines around the globe. Kent stopped at MCRD San “We have Marines serving at Diego as part of his farewell tour every U.S. Embassy in the world,” of Marine Corps installations to said Kent. pass on his legacy before retiring He wanted to assure Marines after 35 years. During his service, regardless of the upcoming he spent seven years as a drill drawdown of troops there is instructor and knows firsthand always a place in the Corps for what it takes to make Marines. good Marines. “It’s always great to get back He explained that Marines to MCRD San Diego,” said are still made the same way as Kent. “You need to know that when he was in recruit training Lance Cpl. Eric Quintanilla the Marines you’re putting out at Parris Island and when he was Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Carlton W. -

Military Ranks Chart

Branch and Rank Description Army Navy / Coast Guard Air Force Marines Rank Code E01 Private (PV1) Seaman Recruit (SR) Airman Basic (AB) Private (PVT) E02 Private (PV2) Seaman Apprentice (SA) Airman (Amn) Private First Class (PFC) E03 Private First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (A1C) Lance Corporal (LCpl) Corporal (CPL) E04 Petty Officer Third Class (PO3) Senior Airman (SrA) Corporal (Cpl) Specialist (SPC) E05 Sergeant (SGT) Petty Officer Second Class (PO2) Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Sergeant (Sgt) E06 Staff Sergeant (SSG) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Technical Sergeant (TSgt) Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Master Sergeant (MSgt) Enlisted E07 Sergeant First Class (SFC) Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Gunnery Sergeant (GySgt) First Sergeant (MSgt) Master Sergeant (MSG) Senior Master Sergeant (SMSgt) Master Sergeant (MSgt) E08 Senior Chief Petty Officer (SCPO) First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (SMSgt) First Sergeant (1stSgt) Sergeant Major (SGM) Chief Master Sergeant (CMSgt) Master Gunnery Sergeant (MGySgt) E09 Master Chief Petty Officer (MCPO) First Sergeant (CMSgt) Command Sergeant Major (CSM) Sergeant Major (SgtMaj) Command Chief Master Sergeant (CCMSgt) O01 Second Lieutenant (2LT) Ensign (ENS) Second Lieutenant (2d Lt) Second Lieutenant (2dLt) O02 First Lieutenant (1LT) Lieutenant Junior Grade (LTJG) First Lieutenant (1st Lt) First Lieutenant (1Lt) O03 Captain (CPT) Lieutenant (LT) Captain (Capt) Captain (Capt) O04 Major (MAJ) Lieutenant Commander (LCDR) Major (Maj) Major (Maj) O05 Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Commander (CDR) Lieutenant Colonel