The Backdrop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Resource, Valuable Archive on Social and Economic History in Western India

H-Asia Resource, Valuable archive on social and economic history in Western India Discussion published by Sumit Guha on Friday, September 2, 2016 Note on a valuable new resource: Haribhakti Collection Department of History, Faculty of Arts The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara, Gujarat-INDIA Foundation: 1949 Eighteenth Century Baroda in Gujarat has not only evidenced the emergence of political potentates in Gaekwads but also the pecuniary mainstays amongst citizens. The foremost were the Haribhaktis’[i]; who are remembered for business success in areas such as money-lending/indigenous banking, coin- changing, traders in private capacity and banking; formation of Gaekwad’s State financial policy- which stimulated rural resources and commercial economy that benefitted in the making of urban Gujarat during the 18th and 19th centuries; and as philanthropists in individual capability. The business acumen and continuous support to Gaekwad fetched honours and titles like Nagar‘ Seth’ and ‘Raj Ratan' ‘Raj Mitra’ ‘Chiranjiva’&c to them by rulers and citizens. Their firm building in Vadodara dates back to last quarter of 19th century; and its location is near Mandvi darwaza in Ghadiali pol popularly known as Haribhakti ni Haveli “…made up of red and yellow wood and …stands as grandeur of 200 years past”. This family as state bankers were Kamvisadars, traders and Nagarseths of Gaekwad`s of Baroda. Their multifunctional role is apparent as we have more than 1000bahis/ account books and around 10,000 loose sheets of correspondence and statements;kundlis, astrological charts, receipts of transactions related to religious donations, grants for educational and health infrastructure, greetings, invitations, admiration and condolence letters etc. -

Chapter II: Study Area

Chapter II: Study Area CHAPTER II: STUDY AREA 2.0 Description of the Study area: Vadodara district is one of the most important districts of Gujarat. It is a leading agriculture district and one of the main contributors to the agricultural production in the state. 2.1 Geographical Location: Vadodara District is a district in the eastern part of the state of Gujarat in western India. It lies between latitudes 21° 45’ and 22° 45’ North and longitudes 72° 48’ and 74° 15’ East having a geographical area of 7,550 km². The district is bounded by Panchmahal and Dahod districts to the North, Anand and Kheda to the West, Bharuch and Narmada districts to the South, and the state of Madhya Pradesh to the East. Administratively, the district is subdivided into twelve talukas, viz. Vadodara, 28 Chapter II: Study Area Karjan, Padra, Savli, Dabhoi, Sankheda, Waghodia, Jetpur Pavi, Chhota Udepur, Naswadi, Tilakwada and Sinor. In the present work, part of Vadodara district is selected as a site of the study area which includes portions from Vadodara, Padra, Dabhoi and Waghodia talukas. Site of study area is shown in map given below (Figure 4). Fig 4. Map showing site of study area The Mahi River passes through the district. Orsang, Dhadhar, Dev, Goma, Jambuva, Vishwamitri, Bhukhi Heran, Mesari, Karad, Men, Ani, Aswini and Sukhi are the small rivers. Minor irrigation dams are constructed across Sukhi and Rami rivers. Geographically, the district comprises of Khambhat Silt in the south-west, Mahi plain in the north-west, Vadodara plain in the middle, Orsang-Heran plain in the mid-east, Vindhyan hills in the east and Narmada gorge in the south-east which merges westwards 29 Chapter II: Study Area with the lower Narmada Valley. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 6/23/09 • PAGE 2 of 8

EADLINE H Battle for Ky NEWS Slots For information about TDN, See page 2 call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2009 RACHEL WORKS HALF FOR MOTHER GOOSE GOLDEN IN THE DAPHNIS Stonestreet Stables and Harold McCormick=s Rachel Golden Century (El Prado {Ire}) made the most of soft Alexandra (Medaglia d=Oro) worked a half in :49 4/5 at early fractions and proved best late to hold off Allybar Churchill Downs yesterday in advance of Saturday=s GI (Ire) (King=s Best) by a length in yesterday=s G3 Prix Mother Goose Daphnis at Longchamp. AHe is a nice horse and won S. at Belmont well,@ said winning jockey Maxime Guyon. AI don=t Park. The filly know what [trainer, Andre] Mr. Fabre is going to do ships to New with him, but he won=t stay much further than that.@ York this Golden Century followed a debut win over this trip at morning. Un- Fontainebleau Apr. 10 with a third when upped to a der exercise mile and a half in a conditions event at Saint-Cloud rider Dominic May 1. Back to a mile at this track last time May 30, Terry, Rachel the homebred returned to winning ways and extended was caught his sequence under an enterprising ride. Allowed to through frac- saunter along behind reluctant rivals shortly after the tions of :13, start, the bay ran freely until settled into his soft lead, :25 and and after kicking at the top of the stretch, was mainly hand ridden to comfortably beat the Wertheimer=s Reed Palmer photo :37.40; she galloped out homebred Allybar. -

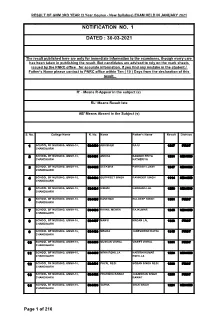

Notification No. 1 Dated : 30-03-2021

RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 30-03-2021 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject (s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent in the Subject (s) S. No. College Name R. No. Name Father's Name Result Division 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534480 ABHISHEK RAJU 1287 FIRST CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534481 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 1231 SECOND CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534482 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 1247 SECOND CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534483 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 1114 SECOND CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534484 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 1250 SECOND CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534485 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 1381 FIRST CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534486 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 1245 SECOND CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534487 MANSI MADAN LAL 1338 FIRST CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534488 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 1315 FIRST CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534489 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 1301 FIRST CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534490 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 1223 SECOND CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534491 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 1296 FIRST CHANDIGARH 13 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534492 PRATIBHA RAWAT JAGMOHAN SINGH 1266 FIRST CHANDIGARH RAWAT 14 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534493 SAPNA SHER SINGH 1221 SECOND CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 216 RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 S. -

Result of Gnm 1St Year Exam Held in December - 2018

RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 31-05-2019 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject,(s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent S. College Name Roll No Name Father Name Result No. 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483001 ABHISHEK RAJU 354 CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483002 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 315 CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483003 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 334 CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483004 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 312 CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483005 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 332 CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483006 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 366 CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483007 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 328 CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483008 MANSI MADAN LAL 356 CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483009 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 347 CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483010 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 355 CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483011 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 324 CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483012 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 346 CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 304 RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 S. -

Gadre 1943.Pdf

- Sri Pratapasimha Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantha-maia MEMOIR No. II. IMPORTANT INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE BARODA STATE. * Vol. I. Price Rs. 5-7-0 A. S. GADRE INTRODUCTION I have ranch pleasure in writing a short introduction to Memoir No, II in 'Sri Pratapsinh Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantharnala Series', Mr, Gadre has edited 12 of the most important epigraphs relating to this part of India some of which are now placed before the public for the first time. of its These throw much light on the history Western India and social and economic institutions, It is hoped that a volume containing the Persian inscriptions will be published shortly. ' ' Dilaram V. T, KRISHNAMACHARI, | Baroda, 5th July 1943. j Dewan. ii FOREWORD The importance of the parts of Gujarat and Kathiawad under the rule of His Highness the Gaekwad of Baroda has been recognised by antiquarians for a the of long time past. The antiquities of Dabhoi and architecture Northern the Archaeo- Gujarat have formed subjects of special monographs published by of India. The Government of Baroda did not however realise the logical Survey of until a necessity of establishing an Archaeological Department the State nearly decade ago. It is hoped that this Department, which has been conducting very useful work in all branches of archaeology, will continue to flourish under the the of enlightened rule of His Highness Maharaja Gaekwad Baroda. , There is limitless scope for the activities of the Archaeological Department in Baroda. The work of the first Gujarat Prehistoric Research Expedition in of the cold weather of 1941-42 has brought to light numerous remains stone age and man in the Vijapuf and Karhi tracts in the North and in Sankheda basin. -

Roshni JULY to SEPTEMBER 2020

Members of Purva Vidarbha Mahila Parishad, Nagpur, Celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi Roshni JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2020 ALL INDIA Women’s ConferenCE Printed at : I G Printers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi-110020 Maharashtra Celebrates Ganesh Chaturthi Ganesh Puja at the home of President -AIWC, Ganesh Puja at the home of President -Mumbai Branch, Smt. Sheela Kakde Smt. Harsha Ladhani Independence Day Celebrations at Head Office Ganesh Puja at Pune Mahila Mandal ROSHNI Contents Journal of the All India Women's Conference Editorial ...................................................................... 2 July - September 2020 President`s Keynote Address at Half Yearly Virtual Meeting .................................... 3 EDITORIAL BOARD -by Smt. Sheela Kakde Editor : Smt. Chitra Sarkar Assistant Editor : Smt. Meenakshi Kumar Experience at Hathras ............................................... 6 Advisors : Smt. Rekha A. Sali -by Smt. Kuljit. Kaur : Smt. Sheela Satyanarayan Editorial Assistants : Smt. Ranjana Gupta An Incident in Hyderabad… How we reacted .... 10 : Smt. Sujata Shivya -by Smt. Geeta Chowdhary President : Smt. Sheela Kakde Maharani Chimnabai II Gaikwad Secretary General : Smt. Kuljit Kaur Treasurer : Smt. Rehana Begum The Illustrious First President of AIWC. .............. 11 -by Smt. Shevata Rai Talwar, Patrons : Smt. Kunti Paul : Dr. Manorama Bawa Are Prodigies Made or Born- A Tribute : Smt. Gomathi Nair to Sarojini Naidu ...................................................... 15 : Smt. Bina Jain -by Smt. Veena Kohli, Patron, AIWC : Smt. Veena Kohli : Smt. Rakesh Dhawan Mangal Murti- Our Hope in the Pandemic ......... 19 -by Smt. Rekha A. Sali AIWC has Consultative Status with UN Observer's Status with UNFCCC Report of Four Zonal Webinars:All India Permanent Representatives : Smt. Sudha Acharya and Women’s Conference `CAUSE PARTNER’ Smt. Seema Upleker (ECOSOC) (UNICEF) of National Foundation for Communal AIWC has affiliation with International Harmony. -

Shivaji the Great

SHIVAJI THE GREAT BY BAL KRISHNA, M. A., PH. D., Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. the Royal Economic Society. London, etc. Professor of Economics and Principal, Rajaram College, Kolhapur, India Part IV Shivaji, The Man and His .Work THE ARYA BOOK DEPOT, Kolhapur COPYRIGHT 1940 the Author Published by The Anther A Note on the Author Dr. Balkrisbna came of a Ksbatriya family of Multan, in the Punjab* Born in 1882, be spent bis boyhood in struggles against mediocrity. For after completing bis primary education he was first apprenticed to a jewel-threader and then to a tailor. It appeared as if he would settle down as a tailor when by a fortunate turn of events he found himself in a Middle Vernacular School. He gave the first sign of talents by standing first in the Vernacular Final ^Examination. Then he joined the Multan High School and passed en to the D. A. V. College, Lahore, from where he took his B. A* degree. Then be joined the Government College, Lahore, and passed bis M. A. with high distinction. During the last part of bis College career, be came under the influence of some great Indian political leaders, especially of Lala Lajpatrai, Sardar Ajitsingh and the Honourable Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and in 1908-9 took an active part in politics. But soon after he was drawn more powerfully to the Arya Samaj. His high place in the M. A. examination would have helped him to a promising career under the Government, but he chose differently. He joined Lala Munshiram ( later Swami Shraddha- Btnd ) *s a worker in the Guruk.ul, Kangri. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Baroda Archives - Southern Circle , Vadodara Unpublished (Huzur Political Office) 1

BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Baroda Archives - Southern Circle , Vadodara Unpublished (Huzur Political Office) 1. Section No - 1, General Dafter No. 1, File Nos. 1 to 8 2. Section No - 11, General Dafter No - 16, File Nos. 1 to 13 3. Section No - 12, General Dafter No - 19, File No - 1 4. Section No - 13, General Dafter No - 20, File Nos - 1 to 6 - A 5. Section No - 14, General Dafter No - 2, File No - 1 6. Section No - 16, General Dafter No - 10, File Nos - 1 to 19 7. Section No - 38, General Dafter No - 8, File Nos - 1 to 8 - B 8. Section No - 65, General Dafter No - 112, File No - 11 9. Section No - 67, General Dafter No - 117, File Nos - 30 to 35 10. Section No.73, General Dafter No. 456, File Nos - 1 to 6 - A 11. Section No - 75, General Dafter No - 457, File No - 1 12. Section No - 77, General Dafter No - 461, File Nos - 11 & 12 13. Section No - 78, General Daft er No - 463, File No - 1 14. Section No - 80, General Dafter No - 466, File Nos - 1 & 2 15. Section No - 88, General Dafter No - 440, File Nos - 1 to 4 16. Section No - 88, General Dafter No - 441, File No - 25 17. Section No - 103, General Dafter No - 143, File Nos - 37 & 38 18. Section No - 177, General Dafter No - 549, File Nos - 1 to 7 19. Section No177, General Dafter No - 550, File Nos - 4 to 16 20. Section No - 199, General Dafter No - 478, File Nos - 1 to 17 21. -

Chapter-Viii Conclusion

CHAPTER - VIII CONCLUSION CHAPTER - VIII CONCLUSION The major characteristic of a pre - modern state, as discussed earlier, was making the power was giving preference to theatrical display over the welfare of the people. These characteristics were visible in the early years of the Baroda State. Khanderao Gae kwad’s period witnessed some sporadic burst of vigor for reformation, could not adhere to it for long enough to be evidence for meaningful results. The period from 1860 to 1881 was a period of transition from pre - modern to early modernity: to some extent compromise between the medieval and the pre - modern. Khanderao did not completely fail to spot the need of introducing visible reforms. The most important reforms brought in by him were streamlining of judicial system and codification of laws; abolition of izara system; organization of revenue system and land settlement; and starting of railways and its expansion. Although these reform s were not of permanent nature, but they did indeed make a base for early modernity . This was because these carried the subst antial components of modernity with need of modification and adjustment or even restructuring. The period of Malharrao could have been the period of real transition and of early modernity if he had put genuine efforts; but he missed the opportunity by indu lging into less important issues. He however introduced few institutions for public instruction - schools and public health - hospitals and dispensaries which can be called a naissance attempt in these fields. If the changes -

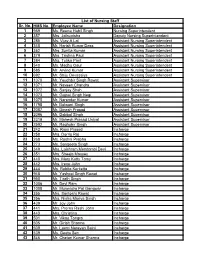

Sr. No. HMS No. Employee Name Designation 1 959 Ms. Reena Habil Singh Nursing Superintendent 2 357 Mrs

List of Nursing Staff Sr. No. HMS No. Employee Name Designation 1 959 Ms. Reena Habil Singh Nursing Superintendent 2 357 Mrs. Jaibunisha Deputy Nursing Superintendent 3 285 Ms. Vijay A Lal Assistant Nursing Superintendent 4 348 Mr. Harish Kumar Dass Assistant Nursing Superintendent 5 362 Mrs. Sunita Kumar Assistant Nursing Superintendent 6 379 Mrs. Trishna Paul Assistant Nursing Superintendent 7 384 Mrs. Tulika Pant Assistant Nursing Superintendent 8 540 Ms. Madhu Gaur Assistant Nursing Superintendent 9 585 Mr. Arvind Kumar Assistant Nursing Superintendent 10 692 Mr. Shiju Devassiya Assistant Nursing Superintendent 11 1070 Mr. Youdhbir Singh Rawat Assistant Supervisor 12 1071 Mr. Naveen Chandra Assistant Supervisor 13 1072 Mr. Sanjay Shah Assistant Supervisor 14 1073 Mr. Gajpal Singh Negi Assistant Supervisor 15 1075 Mr. Narender Kumar Assistant Supervisor 16 1798 Mr. Balwant Singh Assistant Supervisor 17 2087 Mr. Dinesh Prasad Assistant Supervisor 18 2096 Mr. Dabbal Singh Assistant Supervisor 19 2319 Mr. Mahesh Prasad Uniyal Assistant Supervisor 20 2592 Mr. Raghubir Singh Assistant Supervisor 21 242 Ms. Rajni Prasad Incharge 22 258 Mrs. Dorris Raj Incharge 23 268 Ms. Roshni Prabha Incharge 24 273 Ms. Sangeeta Singh Incharge 25 349 Mrs. Laishram Memtombi Devi Incharge 26 351 Mrs. Sheeja Massey Incharge 27 440 Mrs. Mary Kutty Tomy Incharge 28 442 Mrs. Irene John Incharge 29 444 Ms. Rubita Kerketta Incharge 30 948 Mr. Yashpal Singh Rawat Incharge 31 950 Mr. Tirath Singh Incharge 32 1006 Mr. Devi Ram Incharge 33 1008 Mr. Munendra Pal Gangwar Incharge 34 355 Mrs. Santoshi Rawat Incharge 35 356 Mrs. Nisha Mariya Singh Incharge 36 439 Mr.