Leverage: Strengthening Neighborhoods Through Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media and Tactical Considerations for Law Enforcement

Social Media and Tactical Considerations For Law Enforcement This project was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 2011-CK-WX-K016 awarded by the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. References to specific agencies, companies, products, or services should not be considered an endorsement by the author(s) or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the references are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues. The Internet references cited in this publication were valid as of the date of this publication. Given that URLs and websites are in constant flux, neither the author(s) nor the COPS Office can vouch for their current validity. ISBN: 978-1-932582-72-7 e011331543 July 2013 A joint project of: U.S. Department of Justice Police Executive Research Forum Office of Community Oriented Policing Services 1120 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. 145 N Street, N.E. Suite 930 Washington, DC 20530 Washington, DC 20036 To obtain details on COPS Office programs, call the COPS Office Response Center at 800-421-6770. Visit COPS Online at www.cops.usdoj.gov. Contents Foreword ................................................................. iii Acknowledgments ........................................................... iv Introduction ............................................................... .1 Project Background......................................................... -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with the Honorable Michael Nutter

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with The Honorable Michael Nutter PERSON Nutter, Michael A., 1957- Alternative Names: The Honorable Michael Nutter; Life Dates: June 29, 1957- Place of Birth: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Work: Philadelphia, PA Occupations: Mayor Biographical Note Mayor Michael Nutter was born on June 29, 1957, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Mr. and Mrs. Basil Nutter. Nutter and his sister grew up in a row house on Larchwood Avenue in West Philadelphia, where he attended a mostly white Jesuit high school, St. Joseph’s Preparatory School. Nutter received an academic scholarship to St. Joseph’s Preparatory High School where he graduated from in 1975. Nutter then attended where he graduated from in 1975. Nutter then attended the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned his B.A. degree in business administration in 1979. After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania, Nutter worked at the minority-owned investment firm of Pryor, Counts & Co., Inc. He began his political career in 1983 working for Philadelphia Councilman John Anderson until Anderson passed away in 1984. Nutter then joined Angel Ortiz’s campaign for Philadelphia City Council. He was then elected to serve as the Democratic committee nominee for Philadelphia’s 52nd ward in 1986 and in 1991, Nutter was elected Fourth District Councilman, unseating longtime Councilwoman Ann Land. During his fifteen year tenure as fourth district councilman, Nutter created an independent ethics board, restored library funding, and passed the Clean Indoor Air Worker Protection Law. Nutter has served as Chairman of the Pennsylvania Convention Center Authority Board since 2003. -

Michael A. Nutter

Michael A. Nutter Professional History: 98th Mayor City of Philadelphia January, 2008 - January, 2016 Philadelphia City Council District 4 January, 1992 - June, 2006 Selected Honors and Other Service: Saint Joseph's University, Philadelphia, PA Honorary Doctorate in Public Service, honoris causa, 2015 Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA Honorary Doctorate in Public Service, honoris causa, 2008 President, United States Conference of Mayors June, 2012 - June, 2013 Chairman, Pennsylvania Convention Center Authority Board February, 2003 - April, 2007 Education: The Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA B.S. in Economics, 1979 After serving almost 15 years in the Philadelphia City Council, Michael A. Nutter was elected the 98th Mayor of his hometown in November 2007 and took office in January 2008. At his inaugural address, Mayor Nutter pledged to lower crime, improve educational attainment rates, make Philadelphia the greenest city in America and attract new businesses and residents to the city. He also promised to lead an ethical and transparent government focused on providing high quality, efficient and effective customer service. With the support of an experienced, professional staff, Mayor Nutter made significant progress on every pledge: homicides were at an almost 50 year low at the end of his tenure; high school graduation and college degree attainment rates increased significantly; Philadelphia added hundreds of miles in bike lanes and trails and launched the first low-income friendly bike share system in America, called Indego; and Philadelphia 's population grew every year since 2008, including the largest percentage of millennial population growth in the nation. He actively recruited businesses to set up shop in Philadelphia, both domestically and internationally with tax reforms, better business services and international trade missions. -

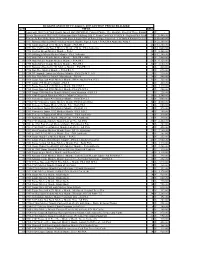

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Architectural Firms

26 PHILADELPHIA BUSINESS JOURNAL THE LIST philadelphiabusinessjournal.com | APRIL 20-26, 2012 Local: 2011 local construction billings* value for Architectural Name for projects/ 2011 2012 Address architect architects/ Local executive/ Prior Rank Phone | Web services employees Specialty services Local projects email firms New Jacobs Engineering Group Inc.** $71.6 $1,194 Architecture, engineer- Pennsylvania State Uni- Michael R. Lorenz Ranked by 2011 local billings* for 2301 Chestnut St., Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 65 ing, interiors, planning, versity, Moore Building 1 215-569-2900 | www.jacobs.com 1,166 landscape architecture addition and renovation architectural services 2 EwingCole $58 $250 Master planning, University of Pennsylva- Mark Hebden 100 N. 6th St., Philadelphia, Pa. 19106 85 programming, architec- nia Health System - Wal- mhebden@ 2 215-923-2020| www.ewingcole.com 280 tural, interior design nut Street fit out ewingcole.com 3 Ballinger $48.3 $373.5 Architecture, engineer- Wistar Institute new Terry D. Steelman 833 Chestnut St., Suite 1400, Philadelphia, Pa. 19107 55 ing, planning, interior research Tower, Barnes tsteelman@ 3 215-446-0900 | www.ballinger-ae.com 236 design Museum Art Edu. Ctr. ballinger-ae.com 13 Stantec Architecture Inc. $35 $250 Architecture, engineer- The LEED certified Dela- Anton Germishuizen 4 1500 Spring Garden, Suite 1100, Philadelphia, Pa. 19130 23 ing, interior design, ware County Community anton.germishuizen@ Below $3.2M 215-665-7000 | www.stantec.com 101 landscape College STEM Complex stantec.com Companies that ranked with 5 Francis Cauffman $23.6 $1,600 Architecture, planning, GlaxoSmithKline Head- Anthony Colciaghi less than $3.2 million in local 5 2000 Market Street, Suite 600, Philadelphia, Pa. -

Mayoral Leadership and Involvement in Education an ACTION GUIDE for SUCCESS

Mayoral Leadership and Involvement in Education AN ACTION GUIDE FOR SUCCESS THE UNITED STATES CONF ERENCE OF MAYO RS Table of Contents: 3 LETTER THE UNITED STATES 4 INTRODUCTION CONFERENCE OF MAYORS 6 THE POLITICAL CONTEXT FOR TODAY’S MAYORAL ROLE IN EDUCATION Manuel A. Diaz Mayor of Miami 8 ISSUES AND CHALLENGES MAYORS FACE IN EDUCATION President Greg Nickels 11 DETERMINING THE MAYOR’S ROLE IN EDUCATION Mayor of Seattle Vice President 14 TYPES OF MAYORAL INVOLVEMENT AND STRATEGIES FOR IMPLEMENTATION Elizabeth A. Kautz Mayor of Burnsville 16 CREATING CONSTRUCTIVE CONDITIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE CHANGE Second Vice President Tom Cochran ISSUES IN FOCUS: CEO and Executive Director 18 School Budgets and Finance -- A Must-Know Issue for Mayors 21 Creating a Portfolio of Schools -- How Mayors Can Help 23 Mayors and the School District Central Office -- The Action Guide has been made possible by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. A Delicate Balance in the Politics of Change 27 MAYOR TO MAYOR: DO’S, DON’TS AND WORDS OF WISDOM 29 CONCLUSION 30 ADDITIONAL READING 33 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Printed on Recycled Paper. DO YOUR PART! PLEASE RECYCLE! May 18, 2009 Dear Mayor: I am pleased to present you with a copy of Mayoral Leadership and Involvement in Education: An Action Guide for Success. This publication provides information, strategies, ideas and examples to assist you in becoming more involved with education in your city. As a mayor, you know how critically important good schools are in promoting the economic development, vitality and image of your city. Many mayors like you have expressed a desire to become more involved in local education issues, policies and programs because you understand the consequences for your city if student performance stagnates and your schools are found “in need of improvement.” Education is a key issue mayors have used to improve public perceptions of their cities. -

AIA 2030 Commitment Measuring Industry Progress Toward 2030 Second Annual Report, May 2012

AIA 2030 Commitment Measuring Industry Progress Toward 2030 Second Annual Report, May 2012 ANNUAL REPORT 1 MAY 2012 Contents 3 Foreword 4 About the AIA 2030 Commitment 6 Firm Operation Actions Data 8 Design Portfolio Data 15 Conclusion 17 Resources 18 AIA 2030 Commitment Program Elements 21 Participating Firms Published 2012 by The American Institute of Architects 1735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20006 Report prepared by Kelly Pickard, Director, Building Science + Technology, The American Institute of Architects With contributions from Greg Mella, AIA, Rand Ekman, AIA, and Marya Graff, Assoc. AIA. Special thanks to Members of the AIA Chicago 2030 Commitment Working Group and the AIA Large Firm Round Table (LFRT) Sustainable Design Leaders for all their contributions to the ongoing development of the program. Special thanks to Marya Graff, Assoc. AIA, for her tremendous contribution to the development and continuing refinement of the AIA 2030 Commitment reporting tool. Design and Production Tony Fletcher Design, tonyfletcher.com ANNUAL REPORT 2 MAY 2012 Foreword By Robert Ivy, FAIA EVP/Chief Executive Officer The American Institute of Architects Architecture and design affect how we work, how we live, how we learn, and how we affect the environment. As a profession, we have to begin thinking differently about what sustainable design means. The pace of climate change mandates an approach that goes beyond meeting energy targets for the occasional sustainable project. We need to have a deeper understanding of the concept of sustainable design and its place in our practice. To truly meet this challenge, sustainability must be embedded into the way we practice. -

Xxxx Xx, 2010

September 20, 2010 The Honorable Harry Reid The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Majority Leader Speaker of the House United States Senate U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable John A. Boehner Minority Leader Minority Leader United States Senate U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Senator Reid, Senator McConnell, Madam Speaker and Mr. Boehner, As members of Building America’s Future, we write to urge action by the House and Senate on legislation that will create a National Infrastructure Bank to help our cities and states find additional methods of financing for projects of regional and national significance. President Obama reiterated his support for this idea on September 6, 2010 and we applaud that announcement. As you may know, the U.S. Conference of Mayors recently endorsed this concept for its potential to correct the dire state of disrepair in which we find our nation’s infrastructure – our roads, bridges, transit systems, drinking and waste water systems and our broadband network. The House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Select Revenue Measures recently held a hearing during which Governor Ed Rendell (D-PA) and Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa (D-Los Angeles) testified about the need for a new entity to focus our nation’s investment power around key projects of regional and national significance. Congress has failed to pass a six-year transportation bill and, as a result, there is no national vision as to how we will plan for the next decade and more. The economic challenges we still face are all the more reason for us to look to the future and find new ways to create jobs, rebuild our decaying infrastructure, improve our quality of life, increase safety and keep our nation economically competitive. -

The Penn Resoluton

Ch"#$i#$ c%i&"'e ("''e)#s "#* *i&i#ishi#$ s+((%ies of i#ex(e#sive oi% )e,+i)e +s 'o *esi$# o+) ci'ies i# )"*ic"%%y *iffe)e#' w"ys. Re*+ci#$ e#e)$y +s"$e "#* c")-o# e&issio#s THE is #ecess")y 'o %i&i' $%o-"% w")&i#$, "**)ess T HE seve)e we"'he) eve#'s "#* )isi#$ se" %eve%s, P "#* f"ce 'he 'h)e"'s of )e*+c'io# of foo* E N N PENN ()o*+c'io#, %oss of -io*ive)si'y, "#* *e(e#- RESOLUT *e#ce o# +#)e%i"-%e e#e)$y s+((%ie)s. RESOLUT!ON These ()o-%e&s ")e +)$e#', $%o-"%, "#* ! ON c%ose%y %i#ke*. Thei) co#ve)$e#ce fo)ces +s Educating Urban Designers "s ()ofessio#"%s co#ce)#e* wi'h -+i%*i#$ f0r Post-Carbon Cities ci'ies 'o )e'hi#k o+) -"sic ()e&ises, &issio#, "#* visio#. !SBN: 978-0-615-45706-2 THE PENN RESOLUT !ON THE PENN RESOLUTION Educating Urban Designers for Post-Carbon Cities The University of Pennsylvania School of Design (PennDesign) is dedicated to promoting excellence in design across a rich diversity of programs – Architecture, City Planning, Landscape Architecture, Fine Arts, Historic Preservation, Digital Media Design, and Visual Studies. Penn Institute for Urban Research (Penn IUR) is a nonpro!t, University of Pennsylvania-based institution dedicated to fostering increased understanding of WE ARE NOT GOING TO BE ABLE TO OPERATE cities and developing new knowledge bases that will be vital in charting the course OUR SPACESHIP EARTH SUCCESSFULLY NOR FOR of local, national, and international urbanization. -

Case Studies on Space Zoning and Passive Façade Strategies for Green Laboratories

ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH, Vol. 22, No. 2(June 2020). pp.41-52 pISSN 1229-6163 eISSN 2383-5575 Case Studies on Space Zoning and Passive Façade Strategies for Green Laboratories Jinho Kim Associate Professor, Division of Architecture and Urban Design, Incheon National University, Incheon, South Korea https://doi.org/10.5659/AIKAR.2020.22.2.41 Abstract Laboratory buildings with specialized equipment and ventilation systems pose challenges in terms of efficient energy use and initial construction costs. Additionally, lab spaces should have flexible and efficient layouts and provide a comfortable indoor research environment. Therefore, this study aims to identify the correlation between the facade of a building and its interior layout from case studies of energy-efficient research labs and to propose passive energy design strategies for the establishment of an optimal research environment. The case studies in this paper were selected from the American Institute of Architects Committee on the Environment Top Ten Projects and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certified research lab projects. In this paper, the passive design strategies of space zoning, façade design devices to control heating and cooling loads were analyzed. Additionally, the relationships between these strategies and the interior lab layouts, lab support spaces, offices, and circulation areas were examined. The following four conclusions were drawn from the analysis of various cases: 1) space zoning for grouping areas with similar energy requirements is performed to concentrate similar heating and cooling demands to simplify the HVAC loads. 2) Public areas such as corridor, atrium, or courtyard can serve as buffer zones that employ passive solar design to minimize the mechanical energy load. -

International Students & Scholars

Spring 2021 International Students & Scholars J1 Exchange Visitors Students & Scholars Pre-Arrival Guide New York City Campus 1 Congratulations on your acceptance to Pace University! This pre-arrival orientation is designed to help you prepare for your journey and your future as a student of Pace University. It will answer questions about what to do before you leave your home country for the U.S., and what you can expect when you arrive. We hope that you and your families stay safe and healthy during these challenging times. We will be in touch with orientation information soon. PACE UNIVERSITY PRE-ARRIVAL GUIDE FOR J-1 INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Page Contents 2 Planning Your Arrival & NYC Campus Map 3 Entry into the United States 3 Student Visa 4 Pre-Departure Checklist 4 Upon Arrival 5 Getting to Your Destination 5 J-1 Student Exchange Orientation 6 Mandatory Check-in 7 International Buddy Program 7 Connect with us on Social Media 7 About Pace 8 Money Matters 9 Support Services 10 New York, NY 11 Weather 2 PLANNING YOUR ARRIVAL We look forward to welcoming you to New York and Pace University. If you have any questions or require further information, please contact: International Students & Scholars Office International Students & Scholars Office New York City Campus Westchester Campuses 163 William Street 861 Bedford Road 16th Floor Kessel Student Center, Room 212 New York, NY 10038 Pleasantville, NY 10570 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Telephone: 1-212-346-1368 Telephone: 1-212-346-1368 3 ENTRY INTO THE UNITED STATES Preparing for Travel Prior to departure to the United States, international students should be sure that they obtain the proper nonimmigrant visa at a United States Embassy or Consulate. -

Architecture 2030 Fact Sheet 1 Architecture 2030 Fact Sheet

Fact Sheet July 19, 2010 Because the Building Sector is key to addressing energy independence and climate change, the success of an energy or climate bill hinges on setting realistic targets for achieving dramatic energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions in the Building Sector. Set correctly, these targets can provide a reasonable and beneficial pace for change that will achieve the reductions necessary within the timeline called for by the scientific community. The following facts make clear what these targets need to be and show conclusively that they are achievable: 1. In 2008, the Building Sector was responsible for: • 50.1% of total annual U.S. energy consumption [1], • 49.1% of total annual U.S. GHG emissions [1], • 74.5% of total annual U.S. electricity consumption [2], and • most of the projected 7.34 QBtu increase in U.S. electricity consumption by 2030 [3]. 2. To constrain global warming within 2 °C, the IPCC projects that developed countries must cut their emissions 25% to 40% below 1990 levels by 2020 and 80% to 95% below 1990 levels by 2050, according to the best available scientific analyses. 3. In order to meet the reductions established by the scientific community, President Obama has called for an 83% reduction of U.S. GHG emissions below 2005 levels by 2050, which equates to approximately 80% below 1990 levels. 4. California, with one of the most aggressive and effective building energy codes in the country, Title 24, uses less than half the electricity and, on average, 44% less building energy consumption per capita when compared to states without a statewide building energy code (see Appendix D).