Appeal Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Babergh District Council (Polstead Footpath No 35) Public Path Diversion Order 2021

NOTICE OF PUBLIC PATH ORDER HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL (POLSTEAD FOOTPATH NO 35) PUBLIC PATH DIVERSION ORDER 2021 The above order, made on 4 February 2021 under section 119 of the Highways Act 1980 will divert the entire width of that part of Polstead Public Footpath No 35 in the vicinity of a storage barn which is currently being converted to a residential dwelling south west of a property known as Spring Hill commencing at Ordnance Survey grid reference (OSGR) TM00053779 then proceeding in an easterly direction for approximately 28 metres to OSGR TM00083779 then in a south easterly direction for approximately 71 metres to OSGR TM00133774 then in an east south easterly direction for approximately 127 metres to join the U4319 road (Shelley Road) at OSGR TM00253769 to a new line running from OSGR TM00053779 and proceeding in a north easterly direction for approximately 15 metres to OSGR TM00073780 then in an easterly direction for approximately 28 metres to OSGR TM00093780 then in a south easterly direction for approximately 36 metres to OSGR TM00123778 then in a south south easterly direction for approximately 68 metres to OSGR TM00163772 then in a south easterly direction on the south west of a fence with the edge of the footpath commencing 0.5 metres from the fence for approximately 84 metres to join the U4319 road (Shelley Road) at OSGR TM00233767 as shown on the order map. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic a copy of the order and the order map and an explanatory statement may be obtained by post or email free of charge by contacting Sharon Berry via email at [email protected] or telephone 01449 724634 or 07801 587853. -

752 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

752 bus time schedule & line map 752 Bures - Sudbury - Long Melford - Bury St Edmunds View In Website Mode The 752 bus line Bures - Sudbury - Long Melford - Bury St Edmunds has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bury St Edmunds: 7:28 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 752 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 752 bus arriving. Direction: Bury St Edmunds 752 bus Time Schedule 46 stops Bury St Edmunds Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:28 AM Church, Bures Tuesday 7:28 AM Spout Lane, Little Cornard Wednesday 7:28 AM Wyatts Lane, Little Cornard Thursday 7:28 AM Chapel Lane, Little Cornard Friday 7:28 AM Grantham Avenue, Great Cornard Saturday Not Operational Rugby Road, Great Cornard Perryƒeld, Sudbury Broom Street, Great Cornard 752 bus Info Direction: Bury St Edmunds Queensway, Great Cornard Stops: 46 Trip Duration: 80 min Beech Road, Great Cornard Line Summary: Church, Bures, Spout Lane, Little Cornard, Wyatts Lane, Little Cornard, Chapel Lane, Highbury Way, Sudbury Little Cornard, Grantham Avenue, Great Cornard, Pot Kiln Lane, Great Cornard Rugby Road, Great Cornard, Broom Street, Great Cornard, Queensway, Great Cornard, Beech Road, Pot Kiln Road, Sudbury Great Cornard, Pot Kiln Lane, Great Cornard, Lindsey Avenue, Great Cornard, Maldon Court, Great Lindsey Avenue, Great Cornard Cornard, Chilton Industrial Estate, Sudbury, Butt Road, Sudbury Homebase, Sudbury, Second Avenue, Sudbury, Acton Lane, Sudbury, Barleycombe, Long Melford, Ropers Maldon Court, Great -

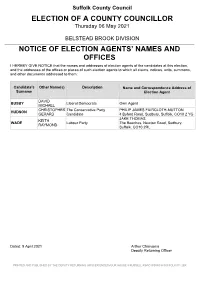

Notice of Election Agents Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent DAVID BUSBY Liberal Democrats Own Agent MICHAEL CHRISTOPHER The Conservative Party PHILIP JAMES FAIRCLOTH-MUTTON HUDSON GERARD Candidate 4 Byford Road, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 2 YG JAKE THOMAS KEITH WADE Labour Party The Beeches, Newton Road, Sudbury, RAYMOND Suffolk, CO10 2RL Dated: 9 April 2021 Arthur Charvonia Deputy Returning Officer PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE DEPUTY RETURNING OFFICER ENDEAVOUR HOUSE 8 RUSSELL ROAD IPSWICH SUFFOLK IP1 2BX Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 COSFORD DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent GORDON MEHRTENS ROBERT LINDSAY Green Party Bildeston House, High Street, Bildeston, JAMES Suffolk, IP7 7EX JAKE THOMAS CHRISTOPHER -

Babergh District Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Babergh District Council Consultation response from Babergh District Council Babergh District Council (BDC) considered the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft proposals for the warding arrangements in the Babergh District at its meeting on 21 November 2017, and made the following comments and observations: South Eastern Parishes Brantham & Holbrook – It was suggested that Stutton & Holbrook should be joined to form a single member ward and that Brantham & Tattingstone form a second single member ward. This would result in electorates of 2104 and 2661 respectively. It is acknowledged the Brantham & Tattingstone pairing is slightly over the 10% variation threshold from the average electorate however this proposal represents better community linkages. Capel St Mary and East Bergholt – There was general support for single member wards for these areas. Chelmondiston – The Council was keen to ensure that the Boundary Commission uses the correct spelling of Chelmondiston (not Chelmondistan) in its future publications. There were comments from some Councillors that Bentley did not share common links with the other areas included in the proposed Chelmondiston Ward, however there did not appear to be an obvious alternative grouping for Bentley without significant alteration to the scheme for the whole of the South Eastern parishes. Copdock & Washbrook - It would be more appropriate for Great and Little Wenham to either be in a ward with Capel St Mary with which the villages share a vicar and the people go to for shops and doctors etc. Or alternatively with Raydon, Holton St Mary and the other villages in that ward as they border Raydon airfield and share issues concerning Notley Enterprise Park. -

School Organisation Review

6108 Sudbury singlePages School Org Review 10/9/09 8:35 am Page 1 School Organisation Review Public Consultation in Sudbury and Great Cornard 28 September 2009 - 18 December 2009 www.suffolk.gov.uk/sor/group3 www.suffolk.gov.uk/sor/group3 www.suffolk.gov.uk/sor/group3 School Organisation Review | 28 September - 18 December 2009 2 2 6108 Sudbury singlePages School Org Review 10/9/09 8:35 am Page 2 6108 Sudbury singlePages School Org Review 10/9/09 8:35 am Page 3 Contents S c 1 Introduction 5 h 2 Process for Change 6 o o 3 Why Change? 10 l 4 Policy Framework and Vision for Learning 15 O 5 Map of Sudbury and Great Cornard Area 16 r g 6 Summary of Preferred Options for Schools in the a Sudbury and Great Cornard Area 17 n 7 Preferred Options for Schools in the Sudbury and Great Cornard Area 20 i s Acton CEVC Primary School 21 a Boxford CEVC Primary School 21 t i Bures CEVC Primary School 22 o n Cavendish Community Primary School 22 Glemsford Community Primary School 22 R e Great Waldingfield CEVC Primary School 23 v Hartest CEVC Primary School 23 i e Lavenham Community Primary School 23 w Long Melford CEVC Primary School 24 | Monks Eleigh CEVC Primary School 24 2 Nayland Primary School 25 8 Pot Kiln Primary School 25 S e St Gregory CEVC Primary School 26 p t St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Primary School 27 e m Stoke-by-Nayland CEVC Primary School 27 b Tudor CEVC Primary School 28 e r Wells Hall Community Primary School 28 - Woodhall Community Primary School 29 1 8 All Saints CEVC Middle School 30 D Great Cornard Middle School 30 e c Stoke-by-Nayland -

Babergh Development Framework to 2031

Summary Document Babergh Development Framework to 2031 Core Strategy Growth Consultation Summer 2010 Babergh Development Framework to 2031 Core Strategy Consultation – Future Growth of Babergh District to 2031 i. Babergh is continuing its work to plan ahead for the district’s long-term future and the first step in this will be the ‘Core Strategy’ part of the Babergh Development Framework (BDF). It is considered that as a starting point for a new Plan, the parameters of future change, development and growth need to be established. ii. It is important to plan for growth and further development to meet future needs of the district, particularly as the Core Strategy will be a long term planning framework. Key questions considered here are growth requirements, the level of housing growth and economic growth to plan for and an outline strategy for how to deliver these. iii. Until recently, future growth targets, particularly those for housing growth, were prescribed in regional level Plans. As these Plans have now been scrapped, there are no given growth targets to use and it is necessary to decide these locally. In planning for the district’s future, a useful sub-division of Babergh can be identified. This is to be used in the BDF and it includes the following 3 main areas: Sudbury / Great Cornard - Western Babergh Hadleigh / Mid Babergh Ipswich Fringe - East Babergh including Shotley peninsula 1. Employment growth in Babergh – determining the scale of growth in employment; plus town centres and tourism 1.1 Babergh is an economically diverse area, with industrial areas at the Ipswich fringe, Sudbury, Hadleigh and Brantham (and other rural areas); traditional retail sectors in the two towns; a high proportion of small businesses; and tourism / leisure based around historic towns / villages and high quality countryside and river estuaries. -

Otley Campus Bus Timetable

OTLEY CAMPUS BUS TIMETABLE 116 / 118: Ipswich to Otley Campus: OC5: Bures to Otley Campus Ipswich, Railway Station (Stand B) 0820 - Bures, Eight Bell Public House R R Ipswich, Old Cattle Market Bus Station (L) 0825 1703 Little Cornard, Spout Lane Bus Shelter R R Ipswich Tower Ramparts, Suffolk Bus Stop - 1658 Great Cornard, Bus stop in Highbury Way 0720 R Westerfield, opp Railway Road 0833 1651 Great Cornard, Bus stop by Shopping Centre 0722 R Witnesham, adj Weyland Road 0839 1645 Sudbury, Bus Station 0727 1753 Swilland, adj Church Lane 0842 1642 Sudbury Industrial Estate, Roundabout A134/ B1115 Bus Layby 0732 1748 Otley Campus 0845 1639 Polstead, Brewers Arms 0742 1738 Hadleigh, Bus Station Magdalen Road 0750 1730 118: Stradbroke to Otley Campus: Sproughton, Wild Man 0805 1715 Stradbroke, Queens Street, Church 0715 1825 Otley Campus 0845 1640 Laxfield, B1117, opp Village Hall 0721 R Badingham, Mill Road, Pound Lodge (S/B) 0730 R OC6: Clacton to Otley Campus Dennington, A1120 B1116, Queens Head 0734 R Clacton, Railway Station 0655 1830 Framlingham, Bridge Street (White Horse, return) 0751 1759 Weeley Heath, Memorial 0705 1820 Kettleborough, The Street, opp Church Road 0802 1752 Weeley, Fiat Garage 0710 1815 Brandeston, Mutton Lane, opp Queens Head 0805 1749 Wivenhoe, The Flag PH (Bus Shelter) 0730 1755 Cretingham, The Street, New Bell 0808 1746 Colchester, Ipswich Road, Premier Inn 0745 1740 Otley, Chapel Road, opp Shop 0816 1738 Capel St Mary, White Horse Pub (AM), A12 Slip road (PM) 0805 1720 Otley Campus 0819 1735 Otley Campus 0845 -

88 Bures Road, Great Cornard, Sudbury, Suffolk

88 BURES ROAD, GREAT CORNARD, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK. CO10 0JE 88 Bures Road, Long Melford 01787 883144 Leavenheath 01206 263007 Clare 01787 277811 Castle Hedingham 01787 463404 Woolpit 01359 245245 Newmarket 01638 669035 Great Cornard, Sudbury,Bury StSuffolk Edmunds 01284 .725525 London 020 78390888 Linton & Villages 01440 784346 88 BURES ROAD, GREAT CORNARD, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK. CO10 0JE Great Cornard is a well-served village with extensive facilities including junior and senior schools, doctors’ surgery, dentist, range of shops (baker/hairdresser/sub-post office), St. Andrews Church, 4 public houses and a regular bus service. The market town of Sudbury is approximately 1 mile distant with many further amenities and a branch line station with connections to London Liverpool Street. The nearby market towns of Colchester (15 miles) and Bury St Edmunds (18 miles) offer extensive amenities, the former providing a mainline station to London Liverpool Street, serving the commuter. This three-bedroom town house has spacious accommodation stretching across three levels. The master bedroom comes with a large en-suite and Juliet balcony and a stunning 21'6 kitchen/dining/living room with a veranda and views over the south westerly facing garden. A beautifully presented town house, close to the Stour Meadows. ENTRANCE HALL: An inviting space with stairs to the first floor and UTILITY ROOM: Fitted with matching units to the kitchen, an integrated doors leading to:- sink and drainer and space for washing machine and tumble dryer. SITTING ROOM: 21’7” x 15’10”. (6.57m x 4.82m). A wonderfully light CLOAKROOM: Fitted WC and wash hand basin. -

Fares Valid 1St April 2021 Fares Guide

Fares valid 1st April 2021 Fares Guide Adult fares table Routes From To Ticket Fare Ticket Fare Ticket Fare 84,84A Sudbury Colchester Adult single: £4.70 Adult return: £8.30 AW Adult weekly: £35 AW 84,784 Gt Horkesley Colchester Adult single: £2.30 Adult return: £4 Adult weekly: £18 84 Stoke by Nayland Colchester Adult single: £4.30 Adult return: £7.50 Adult weekly: £33 84,784 Leavenheath Colchester Adult single: £5.00 Adult return: £8 AW Adult weekly: £35 AW 236 Clare Sudbury Adult single: £4.10 Adult return: £7.20 Adult weekly: £32 236 Glemsford Sudbury Adult single: £3.60 Adult return: £6.20 Adult weekly: £27 236 Cavendish Sudbury Adult single: £3.60 Adult return: £6.20 Adult weekly: £27 236 Long Melford Sudbury Adult single: £1.70 Adult return: £2.90 Adult weekly: £13 236 Long Melford Clare Adult single: £3.60 Adult return: £6.20 Adult weekly: £27 89X Braintree Sudbury Adult single: £2.90 Adult return: £5.20 Adult weekly: £24 89X Halstead Sudbury Adult single: £2.50 Adult return: £4.40 Adult weekly: £16 374 Clare Bury St Edmunds Adult single: £4.50 Adult return: £8.00 Adult weekly: £35 AW 374 Glemsford Bury St Edmunds Adult single: £4.30 Adult return: £7.50 Adult weekly: £33.00 750,753 Bury St Edmunds Sudbury Adult single: £4.70 Adult return: £8.30 Adult weekly: £35 AW 750,753 Long Melford Sudbury Adult single: £1.70 Adult return: £2.90 Adult weekly: £12.00 750,753 Long Melford Bury St Edmunds Adult single: £4.60 Adult return: £8.30 AW Adult weekly: £35 AW 750 Stanningfield Bury St Edmunds Adult single: £3.00 Adult return: £5.30 Adult weekly: £23 750 etc. -

BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL BAMBRIDGE HALL, FURTHER STREET ASSINGTON Grid Reference TL 929 397 List Grade II Conservation Area No D

BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL BAMBRIDGE HALL, FURTHER STREET ASSINGTON Grid Reference TL 929 397 List Grade II Conservation Area No Description An important example of a rural workhouse of c.1780, later converted to 4 cottages. Timber framed and plastered with plaintiled roof. 4 external chimney stacks, 3 set against the rear wall and one on the east gable end. C18-C19 windows and doors. The original building contract survives. Suggested Use Residential Risk Priority C Condition Poor Reason for Risk Numerous maintenance failings including areas of missing plaster, missing tiles at rear and defective rainwater goods. First on Register 2006 Owner/Agent Lord and Lady Bambridge Kiddy, Sparrows, Cox Hill, Boxford, Sudbury CO10 5JG Current Availability Not for sale Notes Listed as ‘Farend’. Some render repairs completed and one rear chimney stack rebuilt but work now stalled. Contact Babergh / Mid Suffolk Heritage Team 01473 825852 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL BARN 100M NE OF BENTLEY HALL, BENTLEY HALL ROAD BENTLEY Grid Reference TM 119 385 List Grade II* Conservation Area No Description A large and fine barn of c.1580. Timber-framed, with brick- nogged side walls and brick parapet end gables. The timber frame has 16 bays, 5 of which originally functioned as stables with a loft above (now removed). Suggested Use Contact local authority Risk Priority A Condition Poor Reason for Risk Redundant. Minor slippage of tiles; structural support to one gable end; walls in poor condition and partly overgrown following demolition of abutting buildings. First on Register 2003 Owner/Agent Mr N Ingleton, Ingleton Group, The Old Rectory, School Lane, Stratford St Mary, Colchester CO7 6LZ (01206 321987) Current Availability For sale Notes This is a nationally important site for bats: 7 types use the building. -

Babergh District Councillor Derek Davis – Ganges Ward (Shotley

Babergh District Councillor Derek Davis – Ganges ward (Shotley & Erwarton) We are into the school summer holidays and as the dad of a teenager I know how difficult it can be for parents keeping their young ones active during these six weeks. It was with that in mind that my first act as Cabinet member for Communities, was to instigate the free swim initiative for all those Babergh residents who are 16 and under. At the moment this is for use at both our Hadleigh and Kingfisher pool in Sudbury. Ideally moving forward, we will be able to liaise with other pools in Suffolk, especially Ipswich for us on the peninsula, but one stroke at a time. This has come about due to our great partnership with Abbeycroft Leisure, that also runs the sports centre at Holbrook, and we are working with them to run outdoor explorer activity days, with at least one coming to Shotley. Details were being finalised at the time of writing this so please keep an eye out on my Facebook page for confirmed dates etc, or go to: https://www.acleisure.com/blog/ Another initiative we have been involved in is the Active Suffolk programme encouraging primary schools to encourage their pupils to take part in a wide range of activities, whether that is the daily mile walk, archery, dance, Tchouckball, or the traditional football and netball. The project, run in partnership with NHS West Suffolk and NHS Ipswich and East Suffolk clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) will run for three years with the support of Active Suffolk, the Active Partnership for Suffolk dedicated to increasing the number of people taking part in sport and physical activity. -

Notice of Poll Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for the Election of a COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named County Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The names, in alphabetical order and other particulars of the candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of the persons signing the nomination papers are as follows:- SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS 16 Two Acres Capel St. Mary Frances Blanchette, Lee BUSBY DAVID MICHAEL Liberal Democrats Ipswich IP9 2XP Gifkins CHRISTOPHER Address in the East Suffolk The Conservative Zachary John Norman, Nathan HUDSON GERARD District Party Candidate Callum Wilson 1-2 Bourne Cottages Bourne Hill WADE KEITH RAYMOND Labour Party Tom Loader, Fiona Loader Wherstead Ipswich IP2 8NH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows:- POLLING POLLING STATION DESCRIPTIONS OF PERSONS DISTRICT ENTITLED TO VOTE THEREAT BBEL Belstead Village Hall Grove Hill Belstead IP8 3LU 1.000-184.000 BBST Burstall Village Hall The Street Burstall IP8 3DY 1.000-187.000 BCHA Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-152.000 BCOP Copdock & Washbrook Village Hall London Road Copdock & Washbrook Ipswich IP8 3JN 1.000-915.500 BHIN Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-531.000 BPNN Holiday Inn Ipswich London Road Ipswich IP2 0UA 1.000-2351.000 BPNS Pinewood - Belstead Brook Muthu Hotel Belstead Road Ipswich IP2 9HB 1.000-923.000 BSPR Sproughton - Tithe Barn Lower Street Sproughton IP8 3AA 1.000-1160.000 BWHE Wherstead Village Hall Off The Street Wherstead IP9 2AH 1.000-244.000 5.