THE GOD PROJECT Books by Stan Lee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Download the Far Horizon

The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell, Danny Wool, Lorna Hanrahan, Mary Musser, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team THE FAR HORIZON BY LUCAS MALET (MRS. MARY ST. LEGER HARRISON) BY THE SAME AUTHOR _The Wages of Sin_ _A Counsel of Perfection_ page 1 / 464 _Colonel Enderby's Wife_ _Little Peter_ _The Carissima_ _The Gateless Barrier_ _The History of Sir Richard Calmady_ "Ask for the Old Paths, where is the Good Way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest."--JEREMIAS. "The good man is the bad man's teacher; the bad man is the material upon which the good man works. If the one does not value his teacher, if the other does not love his material, then despite their sagacity they must go far astray. This is a mystery of great import."--FROM THE SAYINGS OF LAO-TZU. ..."Cherchons a voir les choses comme elles sont, et ne voulons pas avoir plus d'esprit que le bon Dieu! Autrefois on croyait que la canne a sucre seule donnait le sucre, on en tire a peu pres de tout maintenant. Il est de meme de la poesie. Extrayons-la de n'importe quoi, car elle git en page 2 / 464 tout et partout. Pas un atome de matiere qui ne contienne pas la poesie. Et habituons-nous a considerer le monde comme un oeuvre d'art, dont il faut reproduire les procedees dans nos oeuvres."--GUSTAVE FLAUBERT. CHAPTER I Dominic Iglesias stood watching while the lingering June twilight darkened into night. -

WET EXIT Part Two.Pages

! ! Travelogues: WET EXIT Part Two: The Place of Enchantment ! Mars Radcon ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a marlow[films], inc. travelogue #3 This story is dedicated to Doug Whittaker, who forgave me, I hope. ! Copyright © Peregrinator Press and Binding 2019 WET EXIT is a work of un-fiction -- as the author likes to call it -- and hopefully a work of art. Because the story is based upon events which actually occurred and people who actually exist, or did exist, there may be some resemblance between the story's characters and people still living or deceased. The names of all the central characters have been changed and, for the most part, only first names are used. By no means, even if the person upon whom a character is based can be deduced, should it be assumed that the character's fictionalized background or anything they are depicted as saying or doing within the story is any reflection of behavior or speech that ever pertained to the actual person. The illustrations accompanying the text are pencil drawings executed by eye and based upon photographs either captured by the author, discovered in magazines, or downloaded from photo aggregating web sites. In each case, the pencil drawing, al- ready an approximation and typically only a portion of the original image, was scanned and modified using a variety of photo editing software. Ultimately, the illus- trations used in this book are assumed to bear scant, if any, resemblance to the orig- inal photographs. If the owner of any photo, upon perusal, discovers an image too obviously based upon their work and objects to it being used in this way, they only have to contact the author by email and it will be switched out with a different image in all future editions. -

Madame Bandar's Theatre of Love Ghassan Abou-Zeineddine University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2016 Madame Bandar's Theatre of Love Ghassan Abou-Zeineddine University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Abou-Zeineddine, Ghassan, "Madame Bandar's Theatre of Love" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1105. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1105 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MADAME BANDAR’S THEATRE OF LOVE by Ghassan Abou-Zeineddine A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2016 ABSTRACT MADAME BANDAR’S THEATRE OF LOVE by Ghassan Abou-Zeineddine The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Valerie Laken Madame Bandar’s Theatre of Love, a comedic bildungsroman, follows the life of Omar Aladdine in the 1960s and ‘70s as he navigates the historic red-light district in downtown Beirut. At eighteen, Omar works at his father’s grocery store on Mutanabi Street, which is lined with brothels. He becomes enamored with the prostitutes at Madame Bandar’s Theatre of Love, where plays and musical performances are staged, and begins to write romantic plays for the brothel. But when civil war breaks out in the spring of 1975, Mutanabi Street is caught in the crossfire. -

Download the Transcript

1 DEFENSE-2016/12/05 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM INVESTING IN THE FUTURE OF U.S. DEFENSE DURING A TIME OF TRANSITION AT HOME AND ABROAD Washington, D.C. Monday, December 5, 2016 PARTICIPANTS: Moderator: MICHAEL O’HANLON Senior Fellow and Co-Director, Center on 21st Century Security and Intelligence The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: ROBERT O. WORK Deputy Secretary of Defense U.S. Department of Defense Panel: ALAN EASTERLING Corporate Director, Strategic Development Northrop Grumman WILLIAM LYNN Chief Executive Officer Leonardo North America and DRS Technologies, Inc. KELLY MARCHESE Principal Deloitte Consulting LLP * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 DEFENSE-2016/12/05 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. O’HANLON: Well, good afternoon, everyone. Welcome to Brookings. I'm Michael O'Hanlon with the Foreign Policy Program, and I have the real distinct honor of hosting Deputy Secretary of Defense, Robert Work, today. Very glad to have all of you here as well. We will have a discussion up here, the two of us, for a while, then involve you in some questions, and after that part one has ended and Secretary has departed, then we'll bring up the panel to discuss more about the topic of today, which is, as all of you know, innovation in DOD, but specifically, the issue of the third offset, and many other concepts and issues and programs that surround it. And we'll get into anything else, and we'll go in different directions, as well, but that's where I want to begin anyway. -

Filozofické Aspekty Technologií V Komediálním Sci-Fi Seriálu Červený Trpaslík

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Teorie interaktivních médií Dominik Zaplatílek Bakalářská diplomová práce Filozofické aspekty technologií v komediálním sci-fi seriálu Červený trpaslík Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Martin Flašar, Ph.D. 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracoval samostatně a použil jsem literárních a dalších pramenů a informací, které cituji a uvádím v seznamu použité literatury a zdrojů informací. V Brně dne ....................................... Dominik Zaplatílek Poděkování Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat panu PhDr. Martinu Flašarovi, Ph.D za odborné vedení této bakalářské práce a podnětné a cenné připomínky, které pomohly usměrnit tuto práci. Obsah Úvod ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Seriál Červený trpaslík ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Vyobrazené technologie ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Android Kryton ....................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1. Teologická námitka ........................................................................................................ 15 2.1.2. Argument z vědomí ....................................................................................................... 18 2.1.3. Argument z -

Organizing Crime in the Margins | 254

RGANIZING RIME IN THE ARGINS O C M THE ENTERPRISES AND PEOPLE OF THE AMERICAN DRUG TRADE A Thesis Presented for Doctor of Philosophy in Criminology, 2017 Rajeev Gundur Cardiff University To my dad, who planned on living a lot longer than he did. Table of Contents Table of Figures ____________________________________________ vi Table of Photos ____________________________________________ vi Administrative Requirements_________________________________ vii Declaration ________________________________________________________ vii Statement 1: Degree Requirement _____________________________________ vii Statement 2: Claim of Independent Work _______________________________ vii Statement 3: Open Access Consent ____________________________________ vii Summary _________________________________________________________ viii Acknowledgements ________________________________________ ix Author’s Note _____________________________________________ xi I: Getting Organized _________________________________________ 1 One: A Security State of Mind ____________________________________ 2 America the Mistrustful _______________________________________________ 2 Panic About the Drug Trade ___________________________________________ 3 Organized Crime and the Drug Trade: Organizations, Networks, or Beyond? ____ 6 The Settings, Events, and Sequences of the Drug Trade __________________ 10 Understanding Markets: A Strategy for Analysing the Drug Trade __________ 10 Focusing on the Drug Trade Through a Different Lens ______________________ 12 A Look Ahead: Deconstructing -

Red Dwarf” - by Lee Russell

Falling in love with “Red Dwarf” - by Lee Russell It was around 2003 or 2004 when I fell in love with the British sci-fi comedy show “Red Dwarf”. I had been somewhat aware of the series when it launched in 1988 but the external model shots looked so unrealistic that I didn’t bother to try it… what a mistake! My epiphany came late one night after a long session of distance-studying for a degree with the Open University. Feeling very tired and just looking for something to relax with before going to bed, I was suddenly confronted with one of the funniest comedy scenes I had ever seen. That scene was in the Season VIII episode ‘Back in the Red, part 2’. I tuned in just at the moment that Rimmer was using a hammer to test the anaesthetic that he’d applied to his nether regions. I didn’t know the character or the back story that had brought him to that moment, but Chris Barrie’s wonderful acting sucked me in – I was laughing out loud and had suddenly become ‘a Dwarfer’. With one exception, I have loved every series of Red Dwarf, and in this blog I’ll be reflecting on what has made me come to love it so much over the 12 series that have been broadcast to date. For anyone was hasn’t seen Red Dwarf (and if you haven’t, get out there and find a copy now – seriously), the story begins with three of the series’ main characters who have either survived, or are descended from, a radiation accident that occurred three million years ago and killed all of the rest of the crew of the Jupiter Mining Corp ship ‘Red Dwarf’. -

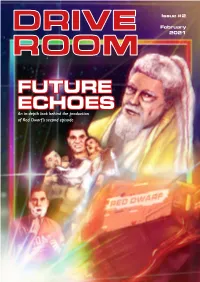

Drive Room Issue 2

Issue #2 February 2021 FUTURE ECHOES An in-depth look behind the production of Red Dwarf’s second episode Contents LEVEL 159 2 Editorial NIVELO 3 Synopsis Well, there was quite a lot to look at for the first ever episode 5 Crew & Other Info of a show, who knew? So this issue will be a little more brief 6 Guest Stars I suspect, a bit leaner, a bit more ‘Green Beret’... but hopefully still a good informative read. 7 Behind The Scenes 11 Adaptations/Other Media My first experience of ‘Future Echoes’ was via the comic-book 14 Character Spotlight version printed in the Red Dwarf Smegazines, and the version 23 Robot Claws used in the Red Dwarf novel. The TV version has therefore 29 always held a bit of a wierd place in my love of the show - as Actor Spotlight much as I can recite it line for line, I’m forever comparing it to 31 Next Issue the other versions! Still, it’s easily one of the best episodes Click/tap on an item to jump to that article. from the first series, if not THE best, and it’s importance in Click/tap the red square at the end of each article to return here. guiding the style of the show cannot be understated. And that’s simple enough that Lister can understand it. “So what is it?” “Thankski Verski Influenced by friends and professionals Muchski Budski!” within the Transformers fandom, I’ve opted to take a leaf out of their book and try and Many thanks to Jordan Hall and James Telfor for create a Red Dwarf fanzine in the vein of providing thier own photographs, memories and other a partwork - where each issue will take a information about the studio filming of Future Echoes deep in-depth dive into a specific episode for this issue. -

12-22-20 Sp Mtg Public Comment POSTING

San Dieguito Union High School District Public Comment December 22, 2020 Special Board Meeting 1 of 51 NAME Comment Item #2 - CLOSED SESSION Anonymous "WHEREAS, the District as yet does not offer in-person instruction for all of its general education population..." Quoted from Mr. Allman's "reopening plan". Can't look at Mrs. Mossey's version, because you have not put it in writing to the public, even though you 'passed' it one week ago. You legally can't open in the purple tier. Game over. Mrs. Young and Mrs. Gibson, we appreciate your service and dedication to our community and all stakeholders. Anonymous I am a parent of 2 students in this district as well as I am a teacher in an elementary school. I feel opening up the school at this time is very negligent. To endanger the health of our teachers and staff by opening the schools at this time - ESPECIALLY as the vaccine is so near does not make any sense. The education standards have always been very high in our district and now with the pandemic they have been lowered. So here you are lowering them even further. Good teachers are leaving. The academic will suffer. Do you know how difficult it is to understand a person wearing a mask through Goggle Meets? And the students in class will not fair any better. I understand that many students need more socialization for their mental health. But this is not the way to go about helping them. How many other options have you tried? Please trust educators to make decisions about education. -

Isaac Asimov Presents the Golden Years of Science Fiction Sixth Series Edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H

Isaac Asimov Presents The Golden Years of Science Fiction Sixth Series Edited By Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg CONTENTS Foreword Introduction THE RED QUEEN’S RACE Isaac Asimov FLAW John D. MacDonald PRIVATE EYE Lewis Padgett MANNA Peter Phillips THE PRISONER IN THE SKULL Lewis Padgett ALIEN EARTH Edmond Hamilton HISTORY LESSON Arthur C. Clarke ETERNITY LOST Clifford D. Simak THE ONLY THING WE LEARN C.M. Kornbluth PRIVATE—KEEP OUT Philip MacDonald THE HURKLE IS A HAPPY BEAST Theodore Sturgeon KALEIDOSCOPE Ray Bradbury DEFENSE MECHANISM Katherine MacLean COLD WAR Harry Kuttner THE WITCHES OF KARRES James H. Schmitz NOT WITH A BANG Damon Knight SPECTATOR SPORT John D. MacDonald THERE WILL COME SOFT RAINS Ray Bradbury DEAR DEVIL Eric Frank Russell SCANNERS LIVE IN VAIN Cordwainer Smith BORN OF MAN AND WOMAN Richard Matheson THE LITTLE BLACK BAG C.M. Kornbluth ENCHANTED VILLAGE A.E. van Vogt ODDY AND ID Alfred Bester THE SACK William Morrison THE SILLY SEASON C.M. Kornbluth MISBEGOTTEN MISSIONARY Isaac Asimov TO SERVE MAN Damon Knight COMING ATTRACTION Fritz Leiber A SUBWAY NAMED MOBIUS A.J. Deutsch PROCESS A.E. van Vogt THE MINDWORM C.M. Kornbluth THE NEW REALITY Charles L. Harness Foreword The years 1949 and 1950 saw into print some of the best science fiction ever written. The technology and the fears brought about by the atomic age pressed new horizons and the concept of absolute mortality upon the world, and it was through this most disturbing vision that the science fiction giants finally found their wings. In this, the sixth volume in the highly acclaimed series of anthologies edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. -

Translating Transphobia: Portrayals of Transgender Australians in the Press 2016 - 2017

Translating Transphobia: Portrayals of Transgender Australians in the Press 2016 - 2017 ** Warning: Report contains transphobic slurs, vilifying language, prejudicial language, and expressions of violence towards transgender people ** © 2018 1 In Memory of Tyra Hunter and Mayang Prasetyo “Denigrated in Death as Well as in Life” 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 2.0 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 3.0 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 4.0 Background Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 11 4.1 Gender Diversity ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 4.2 Gender Dysphoria ........................................................................................................................................................................................................