Becoming-Minor Through Shinsengumi: a Sociology of Popular Culture As a People's Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

The Boshin War

The Boshin War Version 0.1 © 2014 Dadi&Piombo I N Compiled by Alberto Jube THE This set includes lists and additional rules that Gatling allow you to play with Smooth&Rifled the Each Gatling requires 3-4 crew and the cost Boshin War with Smooth&Rifled skirmish is 30 pts per model. rules. You can purchase Smooth&Rifled at Cost of the crew: Regular AV 1/2/3; 10 pts http://www.dadiepiombo.com/smooth.html each; Irregulars AV 2/3/4; 5 pts each. Follow the updates on Smooth&Rifled A Machine Gun fires in a similar way tothe at http://smooth-and-rifled.blogspot.com Group fire. Count 7 dice and add as many dice as the crew. The player can also decide to reduce the dice (rate of fire) to avoid Special rules jamming. A Gatling fires at 30/0. If you roll at least Armour three “1” or three “2” the machine gun is A figure with Armour add 1 to the difficulty to jammed (or is temporary out of ammuni- get an hit in melee (example, a miniature with tions etc). To fix the weapon 3 actions (not C=4 get an hit at 5+) 3 Action Points) are required. These actions are taken by the crew. Mind that one of the Katana and bayonets crew, the gunner, already spends actions A katana works the same as a normal melee when firing. The gunner can also spend ac- weapon (like a sword). Every figure can be tions for aiming. A Gatling can be moved by provided with a katana at +2pts per figure. -

Ocean's Eleven

OCEAN'S 11 screenplay by Ted Griffin based on a screenplay by Harry Brown and Charles Lederer and a story by George Clayton Johnson & Jack Golden Russell LATE PRODUCTION DRAFT Rev. 05/31/01 (Buff) OCEAN'S 11 - Rev. 1/8/01 FADE IN: 1 EMPTY ROOM WITH SINGLE CHAIR 1 We hear a DOOR OPEN and CLOSE, followed by APPROACHING FOOTSTEPS. DANNY OCEAN, dressed in prison fatigues, ENTERS FRAME and sits. VOICE (O.S.) Good morning. DANNY Good morning. VOICE (O.S.) Please state your name for the record. DANNY Daniel Ocean. VOICE (O.S.) Thank you. Mr. Ocean, the purpose of this meeting is to determine whether, if released, you are likely to break the law again. While this was your first conviction, you have been implicated, though never charged, in over a dozen other confidence schemes and frauds. What can you tell us about this? DANNY As you say, ma'am, I was never charged. 2 INT. PAROLE BOARD HEARING ROOM - WIDER VIEW - MORNING 2 Three PAROLE BOARD MEMBERS sit opposite Danny, behind a table. BOARD MEMBER #2 Mr. Ocean, what we're trying to find out is: was there a reason you chose to commit this crime, or was there a reason why you simply got caught this time? DANNY My wife left me. I was upset. I got into a self-destructive pattern. (CONTINUED) OCEAN'S 11 - Rev. 1/8/01 2. 2 CONTINUED: 2 BOARD MEMBER #3 If released, is it likely you would fall back into a similar pattern? DANNY She already left me once. -

By Emily Shelly Won Second Prize in the University of Pittsburgh’S 2008-09 Composition Program Writing Contest

Page | 1 The Journalist September 21, 1874 – 6th Year of Meiji Some time ago, I undertook to write a comprehensive article on the life of Hijikata Toshizo for my newspaper, the Hotaru Shinbun.1 In December, the paper will be printing an expose on the life of Katsu Kaishu,2 a hero of the Meiji Restoration that put the emperor back into power.3 My editor suggested that I write a piece on Hijikata, another supporter of the shogun, to offset it. Hijikata I consider to be the worst of traitors, but the Katsu story had been given to someone else, and as usual, I was stuck with the less glamorous assignment. Nevertheless, if it’s good enough maybe I’ll have a shot at the government correspondent position that just opened up. In this journal I will record the results of my interviews with Katsura Kogoro, Nagakura Shinpachi and one other anonymous source. Luckily, the first person I asked to interview, Katsura Kogoro,4 one of the “Three Great Nobles of the Restoration,”5 agreed to sit down with me and chat over tea about the chaotic years in Kyoto before the Restoration. I counted myself highly privileged. I had to use every connection in my arsenal to finally get permission to interview him. 1 The newspaper that published Nagakura Shinpachi’s oral memoirs of the Shinsengumi. The reporter is fictional, though. 2 Commissioner of the Tokugawa navy. He was a pacifist and considered an expert on Western things. He negotiated the surrender of Edo castle to the Imperial forces in 1867, saving Edo from being swallowed up by war. -

1 YUKISHIROTOMOE E a REPRESENTAÇÃO DA ESPOSA JAPONESA EM SAMURAI X. Magno Rocha Oliveira Fortaleza, Brasil. RESUMO

YUKISHIROTOMOE E A REPRESENTAÇÃO DA ESPOSA JAPONESA EM SAMURAI X. Magno Rocha Oliveira Fortaleza, Brasil. RESUMO Falar de quadrinhos históricos em geral, nos remete a narrativa de um fato histórico. Entretanto ao usarmos a nona arte como meio, e adentrarmos no campo dos mangás, temos uma divergência muito grande com a afirmação anterior. Barbosa (2005, p. 107) comenta que “os japoneses souberam trabalhar os elementos ficcionais com documentos históricos, criando junto ao público leitor um forte elo entre o real e o imaginário popular”, e várias são as obras que exemplificam isso. Podemos destacar Vagabond de Inoue Takehito, que conta a história de Musashi Miyamoto e Peace Maker Kurogane de Nanae Chrono, que conta, de uma maneira bem fantasiosa, as aventuras de Tetsunosuke Ichimura enquanto membro do Shinsengumi. Como citado, não somente temos a exposição de fatos históricos, mas uma mistura de fantasia e realidade, e mesmo assim, podemos afirmar que esses mangás atuam como disseminadores da cultura japonesa tradicional. O autor Nobuhiro Watsuki em Samurai X faz uma representação tanto de fatos históricos, usando-os como plano de fundo para sua obra, como de usos e costumes da sociedade japonesa no conturbado período que foram os últimos anos do Bakufu Tokugawa. Usando como base os estudos feitos pela antropóloga americana Liza Dalby, podemos notar como Tomoe representa com riqueza de detalhes e sutilezas, a mulher e a esposa de camponês japonês daquele período, e isso é visto em seus diálogos e nas suas interações sociais, sejam elas com Kenshin, ou com outros personagens. Assim sendo um mangá age naturalmente como um difusor da História e dos usos e costumes da Sociedade Japonesa Feudal. -

Hino City,Tokyo

English HINO CITY, TOKYO Welcome to the hometown of Japan’s last samurai corps: TheThe ShinsengumiShinsengumi The annual Hino Shinsengumi Festival Hino Shinsengumi Festival is an annual special event which takes place on the second Saturday and Sunday in May. Dress up in Shinsengumi costume and visit Hino’s local Commander Competition Shinsengumi sites. Historically, units one to ten of the Shinsengumi consisted of a total of Day 1 Takahatafudoson 400 people. Every year, Shinsengumi fans from across Japan come together for a competition, through which they are elected to take on the role of a Shinsengumi Shinsengumi Parade commander, such as Kondo Isami or Hijikata Toshizo. Day 2 Takahatafudoson Station Area and Hino Station Area You will be able to participate in the parade if you book in advance, so please come and try it out! Hino’s popular Products Hino City Tourist Information Center Top 5 best-selling souvenirs 1) “Makoto” hand fan(1200 yen) ©IDEA FACTORY/DESIGN FACTORY A folding fan displaying the kanji“makoto” (sincerity), handwritten by Sukekatsu Kawasumi, the chief abbot 1) Hijikata Toshizo Udon (250 yen) of Takahatafudoson Kongo-ji Temple. Three seals have 日野市 been individually impressed onto this product. This is 2) Hijikata Toshizo File Folder (350 yen) Hino_City_Free_Wi-Fi a unique product, which is only available in Hino! Free Wi-Fi is available at 2) "Shinsengumi" Happi (3100yen) 3) Soldier Charm (700 yen) Hino Station, Hino City A "happi" is a type of traditional Japanese coat. 4) “Makoto” Hand Towel (550 yen) This 'Shinsengumi happi' is printed with Dandara Tourist Information Center (mountain stripes) patterns. -

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People”

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015 “Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People” A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015, organized jointly by the Japan Studies Association of Canada (JSAC), the Japanese Association for Canadian Studies (JACS) and the Japan-Canada Interdisciplinary Research Network on Gender, Diversity and Tohoku Reconstruction (JCIRN). Edited by David W. Edgington (University of British Columbia), Norio Ota (York University), Nobuyuki Sato (Chuo University), and Jackie F. Steele (University of Tokyo) © 2016 Japan Studies Association of Canada 1 Table of Contents List of Tables................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 List of Contributors ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................................................. 7 SECTION A: ECONOMICS AND POLITICS IN JAPAN .......................................................................... -

Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: the Significance of “Women’S Art” in Early Modern Japan

Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gregory P. A. Levine, Chair Professor Patricia Berger Professor H. Mack Horton Fall 2010 Copyright by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto 2010. All rights reserved. Abstract Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Gregory Levine, Chair This dissertation focuses on the visual and material culture of Hōkyōji Imperial Buddhist Convent (Hōkyōji ama monzeki jiin) during the Edo period (1600-1868). Situated in Kyoto and in operation since the mid-fourteenth century, Hōkyōji has been the home for women from the highest echelons of society—the nobility and military aristocracy—since its foundation. The objects associated with women in the rarefied position of princess-nun offer an invaluable look into the role of visual and material culture in the lives of elite women in early modern Japan. Art associated with nuns reflects aristocratic upbringing, religious devotion, and individual expression. As such, it defies easy classification: court, convent, sacred, secular, elite, and female are shown to be inadequate labels to identify art associated with women. This study examines visual and material culture through the intersecting factors that inspired, affected, and defined the lives of princess-nuns, broadening the understanding of the significance of art associated with women in Japanese art history. -

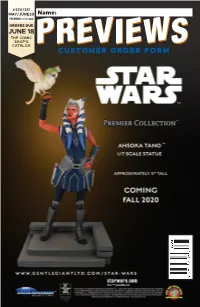

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

Read Book \\ Kaze Hikaru, Volume 16 // SBUIWFKWE0I2

NOHAYJVTMFXX / Doc ^ Kaze Hikaru, Volume 16 Kaze Hikaru, V olume 16 Filesize: 6.82 MB Reviews It is simple in study easier to comprehend. It is one of the most awesome ebook i have read through. You wont truly feel monotony at at any moment of your respective time (that's what catalogs are for concerning in the event you question me). (Clint Sporer) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GP3FFU75KMFQ // eBook # Kaze Hikaru, Volume 16 KAZE HIKARU, VOLUME 16 To download Kaze Hikaru, Volume 16 eBook, you should access the link under and download the ebook or have access to additional information which might be highly relevant to KAZE HIKARU, VOLUME 16 book. Viz Media. Paperback / soback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Kaze Hikaru, Volume 16, Taeko Watanabe, Taeko Watanabe, R to L (Japanese Style). A historial romance set in the time of Rurouni Kenshin! In the year 1863, a time fraught with violent social upheaval, samurai of all walks of life flock to Kyoto in the hope of joining the Mibu-Roshi--a band of warriors united around their undying loyalty to the Shogunate system. In time, this group would become one of the greatest (and most famous) movements in Japanese history.the Shinsengumi! When Sei gets wounded, Soji takes her to Doctor Matsumoto, an old family friend who knows her secret. While in his care, Sei tells him of the resentment she feels toward her father, who neglected his family to pursue his medical practice. Matsumoto reveals the truth about her father and the sacrifice that aected his family's destiny. -

Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives / Editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, Manga Artist

VISION CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PERSPECTIVES WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL MANGA VISION MANGA VISION Cultural and Communicative Perspectives EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell. Copyright of manga artwork is held by Queenie Chan, unless another artist is explicitly stated as its creator in which case it is held by that artist. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective author(s). All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/mv-9781925377064.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Queenie Chan National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Manga vision: cultural and communicative perspectives / editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, manga artist. ISBN: 9781925377064 (paperback) 9781925377071 (epdf) 9781925377361 (epub) Subjects: Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects--Japan. Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects. Comic books, strips, etc., in art. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. -

Diss Master Draft-Pdf

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Visual and Material Culture at Hokyoji Imperial Convent: The Significance of "Women's Art" in Early Modern Japan Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8fq6n1qb Author Yamamoto, Sharon Mitsuko Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gregory P. A. Levine, Chair Professor Patricia Berger Professor H. Mack Horton Fall 2010 Copyright by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto 2010. All rights reserved. Abstract Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Gregory Levine, Chair This dissertation focuses on the visual and material culture of Hōkyōji Imperial Buddhist Convent (Hōkyōji ama monzeki jiin) during the Edo period (1600-1868). Situated in Kyoto and in operation since the mid-fourteenth century, Hōkyōji has been the home for women from the highest echelons of society—the nobility and military aristocracy—since its foundation. The objects associated with women in the rarefied position of princess-nun offer an invaluable look into the role of visual and material culture in the lives of elite women in early modern Japan.