Arxiv:1105.2397V1 [Cs.DS] 12 May 2011 [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vertex Ordering Problems in Directed Graph Streams∗

Vertex Ordering Problems in Directed Graph Streams∗ Amit Chakrabartiy Prantar Ghoshz Andrew McGregorx Sofya Vorotnikova{ Abstract constant-pass algorithms for directed reachability [12]. We consider directed graph algorithms in a streaming setting, This is rather unfortunate given that many of the mas- focusing on problems concerning orderings of the vertices. sive graphs often mentioned in the context of motivating This includes such fundamental problems as topological work on graph streaming are directed, e.g., hyperlinks, sorting and acyclicity testing. We also study the related citations, and Twitter \follows" all correspond to di- problems of finding a minimum feedback arc set (edges rected edges. whose removal yields an acyclic graph), and finding a sink In this paper we consider the complexity of a variety vertex. We are interested in both adversarially-ordered and of fundamental problems related to vertex ordering in randomly-ordered streams. For arbitrary input graphs with directed graphs. For example, one basic problem that 1 edges ordered adversarially, we show that most of these motivated much of this work is as follows: given a problems have high space complexity, precluding sublinear- stream consisting of edges of an acyclic graph in an space solutions. Some lower bounds also apply when the arbitrary order, how much memory is required to return stream is randomly ordered: e.g., in our most technical result a topological ordering of the graph? In the offline we show that testing acyclicity in the p-pass random-order setting, this can be computed in O(m + n) time using model requires roughly n1+1=p space. -

Algorithms (Decrease-And-Conquer)

Algorithms (Decrease-and-Conquer) Pramod Ganapathi Department of Computer Science State University of New York at Stony Brook August 22, 2021 1 Contents Concepts 1. Decrease by constant Topological sorting 2. Decrease by constant factor Lighter ball Josephus problem 3. Variable size decrease Selection problem ............................................................... Problems Stooge sort 2 Contributors Ayush Sharma 3 Decrease-and-conquer Problem(n) [Step 1. Decrease] Subproblem(n0) [Step 2. Conquer] Subsolution [Step 3. Combine] Solution 4 Types of decrease-and-conquer Decrease by constant. n0 = n − c for some constant c Decrease by constant factor. n0 = n/c for some constant c Variable size decrease. n0 = n − c for some variable c 5 Decrease by constant Size of instance is reduced by the same constant in each iteration of the algorithm Decrease by 1 is common Examples: Array sum Array search Find maximum/minimum element Integer product Exponentiation Topological sorting 6 Decrease by constant factor Size of instance is reduced by the same constant factor in each iteration of the algorithm Decrease by factor 2 is common Examples: Binary search Search/insert/delete in balanced search tree Fake coin problem Josephus problem 7 Variable size decrease Size of instance is reduced by a variable in each iteration of the algorithm Examples: Selection problem Quicksort Search/insert/delete in binary search tree Interpolation search 8 Decrease by Constant HOME 9 Topological sorting Problem Topological sorting of vertices of a directed acyclic graph is an ordering of the vertices v1, v2, . , vn in such a way that there is an edge directed towards vertex vj from vertex vi, then vi comes before vj. -

Topological Sort (An Application of DFS)

Topological Sort (an application of DFS) CSC263 Tutorial 9 Topological sort • We have a set of tasks and a set of dependencies (precedence constraints) of form “task A must be done before task B” • Topological sort : An ordering of the tasks that conforms with the given dependencies • Goal : Find a topological sort of the tasks or decide that there is no such ordering Examples • Scheduling : When scheduling task graphs in distributed systems, usually we first need to sort the tasks topologically ...and then assign them to resources (the most efficient scheduling is an NP-complete problem) • Or during compilation to order modules/libraries d c a g f b e Examples • Resolving dependencies : apt-get uses topological sorting to obtain the admissible sequence in which a set of Debian packages can be installed/removed Topological sort more formally • Suppose that in a directed graph G = (V, E) vertices V represent tasks, and each edge ( u, v)∊E means that task u must be done before task v • What is an ordering of vertices 1, ..., | V| such that for every edge ( u, v), u appears before v in the ordering? • Such an ordering is called a topological sort of G • Note: there can be multiple topological sorts of G Topological sort more formally • Is it possible to execute all the tasks in G in an order that respects all the precedence requirements given by the graph edges? • The answer is " yes " if and only if the directed graph G has no cycle ! (otherwise we have a deadlock ) • Such a G is called a Directed Acyclic Graph, or just a DAG Algorithm for -

6.006 Course Notes

6.006 Course Notes Wanlin Li Fall 2018 1 September 6 • Computation • Definition. Problem: matching inputs to correct outputs • Definition. Algorithm: procedure/function matching each input to single out- put, correct if matches problem • Want program to be able to handle infinite space of inputs, arbitrarily large size of input • Want finite and efficient program, need recursive code • Efficiency determined by asymptotic growth Θ() • O(f(n)) is all functions below order of growth of f(n) • Ω(f(n)) is all functions above order of growth of f(n) • Θ(f(n)) is tight bound • Definition. Log-linear: Θ(n log n) Θ(nc) • Definition. Exponential: b • Algorithm generally considered efficient if runs in polynomial time • Model of computation: computer has memory (RAM - random access memory) and CPU for performing computation; what operations are allowed in constant time • CPU has registers to access and process memory address, needs log n bits to handle size n input • Memory chunked into “words” of size at least log n 1 6.006 Wanlin Li 32 10 • E.g. 32 bit machine can handle 2 ∼ 4 GB, 64 bit machine can handle 10 GB • Model of computaiton in word-RAM • Ways to solve algorithms problem: design new algorithm or reduce to already known algorithm (particularly search in data structure, sort, shortest path) • Classification of algorithms based on graph on function calls • Class examples and design paradigms: brute force (completely disconnected), decrease and conquer (path), divide and conquer (tree with branches), dynamic programming (directed acyclic graph), greedy (choose which paths on directed acyclic graph to take) • Computation doesn’t have to be a tree, just has to be directed acyclic graph 2 September 11 • Example. -

Verified Textbook Algorithms

Verified Textbook Algorithms A Biased Survey Tobias Nipkow[0000−0003−0730−515X] and Manuel Eberl[0000−0002−4263−6571] and Maximilian P. L. Haslbeck[0000−0003−4306−869X] Technische Universität München Abstract. This article surveys the state of the art of verifying standard textbook algorithms. We focus largely on the classic text by Cormen et al. Both correctness and running time complexity are considered. 1 Introduction Correctness proofs of algorithms are one of the main motivations for computer- based theorem proving. This survey focuses on the verification (which for us always means machine-checked) of textbook algorithms. Their often tricky na- ture means that for the most part they are verified with interactive theorem provers (ITPs). We explicitly cover running time analyses of algorithms, but for reasons of space only those analyses employing ITPs. The rich area of automatic resource analysis (e.g. the work by Jan Hoffmann et al. [103,104]) is out of scope. The following theorem provers appear in our survey and are listed here in alphabetic order: ACL2 [111], Agda [31], Coq [25], HOL4 [181], Isabelle/HOL [151,150], KeY [7], KIV [63], Minlog [21], Mizar [17], Nqthm [34], PVS [157], Why3 [75] (which is primarily automatic). We always indicate which ITP was used in a particular verification, unless it was Isabelle/HOL (which we abbreviate to Isabelle from now on), which remains implicit. Some references to Isabelle formalizations lead into the Archive of Formal Proofs (AFP) [1], an online library of Isabelle proofs. There are a number of algorithm verification frameworks built on top of individual theorem provers. -

Visvesvaraya Technological University a Project Report

` VISVESVARAYA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY “Jnana Sangama”, Belagavi – 590 018 A PROJECT REPORT ON “PREDICTIVE SCHEDULING OF SORTING ALGORITHMS” Submitted in partial fulfillment for the award of the degree of BACHELOR OF ENGINEERING IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING BY RANJIT KUMAR SHA (1NH13CS092) SANDIP SHAH (1NH13CS101) SAURABH RAI (1NH13CS104) GAURAV KUMAR (1NH13CS718) Under the guidance of Ms. Sridevi (Senior Assistant Professor, Dept. of CSE, NHCE) DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING NEW HORIZON COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING (ISO-9001:2000 certified, Accredited by NAAC ‘A’, Permanently affiliated to VTU) Outer Ring Road, Panathur Post, Near Marathalli, Bangalore – 560103 ` NEW HORIZON COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING (ISO-9001:2000 certified, Accredited by NAAC ‘A’ Permanently affiliated to VTU) Outer Ring Road, Panathur Post, Near Marathalli, Bangalore-560 103 DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING CERTIFICATE Certified that the project work entitled “PREDICTIVE SCHEDULING OF SORTING ALGORITHMS” carried out by RANJIT KUMAR SHA (1NH13CS092), SANDIP SHAH (1NH13CS101), SAURABH RAI (1NH13CS104) and GAURAV KUMAR (1NH13CS718) bonafide students of NEW HORIZON COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING in partial fulfillment for the award of Bachelor of Engineering in Computer Science and Engineering of the Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belagavi during the year 2016-2017. It is certified that all corrections/suggestions indicated for Internal Assessment have been incorporated in the report deposited in the department library. The project report has been approved as it satisfies the academic requirements in respect of Project work prescribed for the Degree. Name & Signature of Guide Name Signature of HOD Signature of Principal (Ms. Sridevi) (Dr. Prashanth C.S.R.) (Dr. Manjunatha) External Viva Name of Examiner Signature with date 1. -

CS 61B Final Exam Guerrilla Section Spring 2018 May 5, 2018

CS 61B Final Exam Guerrilla Section Spring 2018 May 5, 2018 Instructions Form a small group. Start on the first problem. Check off with a helper or discuss your solution process with another group once everyone understands how to solve the first problem and then repeat for the second problem . You may not move to the next problem until you check off or discuss with another group and everyone understands why the solution is what it is. You may use any course resources at your disposal: the purpose of this review session is to have everyone learning together as a group. 1 The Tortoise or the Hare 1.1 Given an undirected graph G = (V; E) and an edge e = (s; t) in G, describe an O(jV j + jEj) time algorithm to determine whether G has a cycle containing e. Remove e from the graph. Then, run DFS or BFS starting at s to find t. If a path already exists from s to t, then adding e would create a cycle. 1.2 Given a connected, undirected, and weighted graph, describe an algorithm to con- struct a set with as few edges as possible such that if those edges were removed, there would be no cycles in the remaining graph. Additionally, choose edges such that the sum of the weights of the edges you remove is minimized. This algorithm must be as fast as possible. 1. Negate all edges. 2. Form an MST via Kruskal's or Prim's algorithm. 3. Return the set of all edges not in the MST (undo negation). -

A Low Complexity Topological Sorting Algorithm for Directed Acyclic Graph

International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing, Vol. 4, No. 2, April 2014 A Low Complexity Topological Sorting Algorithm for Directed Acyclic Graph Renkun Liu then return error (graph has at Abstract—In a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), vertex A and least one cycle) vertex B are connected by a directed edge AB which shows that else return L (a topologically A comes before B in the ordering. In this way, we can find a sorted order) sorting algorithm totally different from Kahn or DFS algorithms, the directed edge already tells us the order of the Because we need to check every vertex and every edge for nodes, so that it can simply be sorted by re-ordering the nodes the “start nodes”, then sorting will check everything over according to the edges from a Direction Matrix. No vertex is again, so the complexity is O(E+V). specifically chosen, which makes the complexity to be O*E. An alternative algorithm for topological sorting is based on Then we can get an algorithm that has much lower complexity than Kahn and DFS. At last, the implement of the algorithm by Depth-First Search (DFS) [2]. For this algorithm, edges point matlab script will be shown in the appendix part. in the opposite direction as the previous algorithm. The algorithm loops through each node of the graph, in an Index Terms—DAG, algorithm, complexity, matlab. arbitrary order, initiating a depth-first search that terminates when it hits any node that has already been visited since the beginning of the topological sort: I. -

Introduction to Graphs ・V = Nodes

Undirected graphs Notation. G = (V, E) Introduction to Graphs ・V = nodes. ・E = edges between pairs of nodes. ・Captures pairwise relationship between objects. Tyler Moore ・Graph size parameters: n = | V |, m = | E |. CS 2123, The University of Tulsa V = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 } Some slides created by or adapted from Dr. Kevin Wayne. For more information see E = { 1-2, 1-3, 2-3, 2-4, 2-5, 3-5, 3-7, 3-8, 4-5, 5-6, 7-8 } http://www.cs.princeton.edu/~wayne/kleinberg-tardos m = 11, n = 8 3 2 / 36 One week of Enron emails The evolution of FCC lobbying coalitions 4 “The Evolution of FCC Lobbying Coalitions” by Pierre de Vries in JoSS Visualization Symposium 2010 5 3 / 36 4 / 36 The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network Over 32 Years educational level; the ego’s obesity status at the ing both their weights. We estimated these mod- previous time point (t); and most pertinent, the els in varied ego–alter pair types. alter’s obesity status at times t and t + 1.25 We To evaluate the possibility that omitted vari- used generalized estimating equations to account ables or unobserved events might explain the as- for multiple observations of the same ego across sociations, we examined how the type or direc- examinations and across ego–alter pairs.26 We tion of the social relationship between the ego assumed an independent working correlation and the alter affected the association between the structure for the clusters.26,27 ego’s obesity and the alter’s obesity. -

CS 270 Algorithms

CS 270 Algorithms Oliver Week 11 Kullmann Introduction Algorithms and their Revision analysis Graphs Data 1 Introduction structures Conclusion 2 Algorithms and their analysis 3 Graphs 4 Data structures 5 Conclusion CS 270 General remarks Algorithms Oliver Kullmann You need to be able to perform the following: Introduction Algorithms and their Reproducing all definitions. analysis Performing all computations on (arbitrary) examples. Graphs Data Explaining all algorithms in (written) words (possibly using structures some mathematical formalism). Conclusion Stating the time complexity in term of Θ. Check all this by writing it all down! Actually understanding the definitions and algorithms helps a lot (but sometimes “understanding” can become a trap). CS 270 How to prepare Algorithms Oliver Kullmann All information is on the course homepage Introduction Algorithms and their analysis Graphs http://cs.swan.ac.uk/~csoliver/Algorithms201314/index.html Data structures Conclusion Go through all lectures (perhaps you download the slides again — certain additions have been made). Go through the courseworks and their solutions. Go through the lab sessions (run it!). Use the learning goals! CS 270 On the exam Algorithms Oliver Kullmann Introduction Algorithms and their analysis We use the “two-out-of-three” format. Graphs Data Give us a chance to give you marks — write down structures something! Conclusion Actually, better write down a lot — in the second or third round, after answering all questions. Examples are typically helpful. CS 270 The general structure of the module Algorithms Oliver Kullmann Introduction Algorithms and their analysis Graphs Data 1 Weeks 1-3: Algorithms and their analysis structures 2 Weeks 4-5: Graphs — BFS and DFS. -

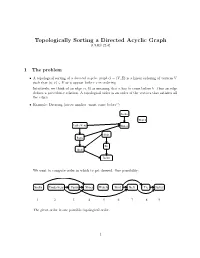

Topologically Sorting a Directed Acyclic Graph (CLRS 22.4)

Topologically Sorting a Directed Acyclic Graph (CLRS 22.4) 1 The problem • A topological sorting of a directed acyclic graph G = (V; E) is a linear ordering of vertices V such that (u; v) 2 E ) u appear before v in ordering. Intuitively, we think of an edge (a; b) as meaning that a has to come before b|thus an edge defines a precedence relation. A topological order is an order of the vertices that satisfies all the edges. • Example: Dressing (arrow implies \must come before") Socks Watch Underwear Shoes Shirt Pants Tie Belt Jacket We want to compute order in which to get dressed. One possibility: Socks Underwear Pants Shoes WatchShirt Belt Tie Jacket 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 The given order is one possible topological order. 1 2 Does a tpopological order always exist? • If the graph has a cycle, a topological order cannot exist. Imagine the simplest cycle, consist- ing of two edges: (a; b) and (b; a). A topological ordering , if it existed, would have to satisfy that a must come before b and b must come before a. This is not possible. • Now consider we have a graph without cycles; this is usually referred to as a DAG (directed acyclic graph). Does any DAG have a topological order? The answer is YES. We'll prove this below indirectly by showing that the toposort algorithm always gives a valid ordering when run on any DAG. 3 Topological sort via DFS It turns out that we can get topological order based on DFS. -

Graphs 1 What Is a Graph? in a Layman’S Terms: a Graph Is a Set of Vertices Or Nodes “ Which Are Connected by Edges

Graphs 1 What is a Graph? In a layman’s terms: A graph is a set of vertices or nodes “ which are connected by edges. Tree v Graph? “ Tree v Graph? “ “ In Short: Tree is a restricted form of a graph Kinds of Graphs ● Undirected or Directed ● Cyclic or Acyclic ● Weighted or Unweighted ● Simple ● And more! Some additional vocabulary: Adjacent/Neighbors, Degree, Loop. Graph Representation Adjacency Matrix Adjacency List V x V boolean (or numerical) Collection of lists (X) where X[i} matrix where an entry X[a][b] is contains the vertices which are true (or 1) if there exists an edge the neighbors of vertex i. from vertex a to b. SPACE O(V+E)) SPACE O(V^2) BFS / DFS BFS/DFS What is BFS? What is DFS? BFS - Boolean visited” array -> why? - Expand the root and visit all of its children before going to childrens children - So what data structures would be best for this? DFS - Boolean -> why? - Recursion - Go deep into a node - So which is better BFS or DFS? - Lets try implementing before we move on! Tries ● A type of tree - used for characters usually ● Allows for specific quick lookups ● Think of this anytime you have lookup problems (prefix based search, store dictionary, etc) ● Let’s see an example. Insert/Search/Delete ● How would you do each of these? 2 Let’s trie some problems! Q1: Implementation ● Implement either BFS or DFS Q2: Detect a Graph Cycle ● Undirected or Directed ● Cyclic or Acyclic ● Weighted or Unweighted ● Simple ● And more! Some additional vocabulary: Adjacent/Neighbors, Degree, Loop.