TST UTQAP Self-Study Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master of Divinity

Back to Table of Contents Master’s Degree Programs Master of Divinity Vocational Calling To serve in a wide variety of ministerial callings, including pastoral ministry, youth ministry, campus ministry, chaplaincy, and missions. Basic Ministerial Competency Component Electives Component (75 hours) (9 hours) Biblical Exposition Competency (23 hours) Free Electives (9 hours) Encountering the Biblical World 2 hours Exploring the Old Testament 3 hours Total Required: 84 hours Exploring the New Testament 3 hours Introduction to Biblical Hermeneutics 3 hours Introductory Hebrew Grammar 3 hours *All graduate students must take this course during orientation in their Intermediate Hebrew Grammar for OT Exegesis 3 hours first semester: however, students will not receive a credit hour or be Introductory Greek Grammar 3 hours charged for the course. Intermediate Greek Grammar for NT Exegesis 3 hours **Students who do not have a pastoral ministry calling (e.g., pastor, Christian Theological Heritage Competency (16 hours) ministry staff, chaplain, or church planter) may choose to take Christian Ministry instead of Pastoral Ministry. Systematic Theology 1 3 hours Systematic Theology 2 3 hours ***Students not called into a preaching ministry may choose to take History of Christianity: Early-Medieval 2 hours Teaching the Bible instead of Proclaiming the Bible, and Teaching Practicum History of Christianity: Reformation-Modern 3 hours instead of Preaching Practicum. Students who take Teaching the Bible must Baptist Heritage 2 hours take the Teaching Practicum course. Philosophy of Religion OR Christian Apologetics 3 hours NOBTS, SBC, and Cooperative Program * Disciple Making Competency (9 hours) Supervised Ministry 1: Personal Evangelism Practicum 2 hours Church Evangelism 2 hours For further information, please contact: Christian Missions 3 hours • Dr. -

University of Toronto Quality Assurance Process REVIEW SUMMARY Toronto School of Theology Published October 2012 Commissioning O

University of Toronto Quality Assurance Process REVIEW SUMMARY Toronto School of Theology Published October 2012 Commissioning Officer: Provost, University of Toronto Programs offered conjointly by the Toronto School of Theology and the University of Toronto:* Emmanuel College • Master of Divinity • Master of Pastoral Studies • Master of Religious Education • Master of Sacred Music • Master of Theological Studies • Doctor of Ministry** • Master of Theology** • Doctor of Theology** Knox College • Master of Divinity • Master of Religious Education • Master of Theological Studies • Doctor of Ministry** • Master of Theology** • Doctor of Theology** Regis College • Master of Arts in Ministry and Spirituality • Master of Divinity • Master of Theological Studies • Doctor of Ministry** • Master of Theology** • Doctor of Theology** St. Augustine’s Seminary • Master of Divinity • Master of Religious Education • Master of Theological Studies University of St. Michael's College Faculty of Theology • Master of Divinity • Master of Religious Education • Master of Theological Studies • Doctor of Ministry** • Master of Theology** 2 • Doctor of Theology** University of Trinity College, Faculty of Divinity • Master of Divinity • Master of Theological Studies • Doctor of Ministry** • Master of Theology** • Doctor of Theology** Wycliffe College • Master of Divinity • Master of Religion*** • Master of Theological Studies • Doctor of Ministry** • Master of Theology** • Doctor of Theology** * Conjoint programs are at the “Second entry undergraduate/Basic” level unless otherwise noted. ** “Graduate/Advanced level program” *** Closure approved March 14, 2012 Reviewers 1. Professor Ellen Reviewers Aitken, McGill University 2. Professor David F. Ford, University of Cambridge 3. Professor Richard Rosengarten, University of Chicago Date of Review Visit January 10-11, 2012 Previous reviews This review of these conjoint programs is the first full review under the UTQAP. -

Download Degree Plan

Doctor of MINISTRY LEARNING FOR LEADERSHIP PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS A Nashotah House Doctor of Ministry (DMin) Classes meet in one-week residential intensive is a professional degree designed for those sessions in summer and winter, during which engaged in full-time, fruitful ministry who seek a time students are immersed in the beauty and deeper engagement with biblical, historical, and community of Nashotah House: twice-daily theological reflection with an eye toward direct worship, shared meals, challenging academics, and practical application in the lives of those and warm collegiality. The remainder of the under their spiritual care. coursework is completed online and/or in the student’s ministry context. Guided and supervised by resident and affiliate faculty, the DMin project is introduced via a Access to all Frances Donaldson Library week-long residential doctoral seminar. Students resources: 110,000 print volumes, 50,000 are taught research methodology and guided e-books, and millions of digital journal articles. in designing a study which creatively engages Editing assistance available prior to presentation contemporary culture with spiritual principles, of the project and publication of written toward the goal of spiritual growth and dissertation, if desired. enhanced ministry leadership for all engaged in the project. The DMin program normally requires four to six years to complete. DOCTOR OF MINISTRY (30 CREDITS) CORE COURSE - 800 LEVEL ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS 3 cr. Doctoral Seminar (Methodology) Applicants for the Doctor of Ministry degree program will normally hold an MDiv or equivalent theological DOCTORAL ELECTIVES - 800 LEVEL degree (with a minimum GPA of 3.0 on a four-point 18 cr. -

Proposal for a New Conjoint Master of Arts in Theological Studies, Toronto School of Theology

FOR RECOMMENDATION PUBLIC OPEN SESSION TO: Committee on Academic Policy and Programs SPONSOR: Sioban Nelson, Vice-Provost, Academic Programs CONTACT INFO: (416) 978-2122, [email protected] PRESENTER: See Sponsor CONTACT INFO: DATE: March 11, 2016 to March 30, 2016 AGENDA ITEM: 1 ITEM IDENTIFICATION: Proposal for a new conjoint Master of Arts in Theological Studies, Toronto School of Theology JURISDICTIONAL INFORMATION: The Committee on Academic Policy and Programs has the authority to recommend to the Academic Board for approval new graduate programs and degrees. (AP&P Terms of Reference, Section 4.4.a.ii) GOVERNANCE PATH: 1. Committee on Academic Policy and Programs [for recommendation] (March 30, 2016) 2. Academic Board [for approval] (April 21, 2016) 3. Executive Committee [for confirmation] (May 9, 2016) PREVIOUS ACTION TAKEN: The proposal for the conjoint Master of Arts in Theological Studies received approval from the Toronto School of Theology Academic Council on March 4, 2016. HIGHLIGHTS: This is a proposal for a new research master’s program in Theological Studies. The proposed M.A. will be offered conjointly by the University of Toronto (U of T) and the Toronto School of Theology (TST). Page 1 of 3 Committee on Academic Policy and Programs – Proposal for conjoint M.A. in Theological Studies Background TST and the seven theological colleges associated with it are institutionally independent of U of T and have their own systems of governance. The relationship between U of T and TST arose as follows: Whereas European universities from their founding included the offering of degrees in theology as one of their roles, historically, U of T’s charter did not include the power to grant degrees in theology. -

THE SCHOOL of THEOLOGY Catalog 2014–2015 SCHOOL of THEOLOGY CATALOG 2014–2015

THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY Catalog 2014–2015 SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY CATALOG 2014–2015 The School of Theology is a division of the University of the South. It comprises an accredited seminary of the Episcopal Church and a programs center, that offers on-site and distance learning theological education. It is accredited by the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to offer the degrees of Master of Divinity, Master of Arts, Master of Sacred Theology, and Doctor of Ministry. The School of Theology is located atop the Cumberland Plateau, 95 miles southeast of Nashville and 45 miles northwest of Chattanooga. For additional information write or phone: The School of Theology The University of the South 335 Tennessee Avenue Sewanee, TN 37383-0001 800.722.1974 Email: [email protected] Website: theology.sewanee.edu The University of the South’s policy against discrimination, harassment, sexual misconduct, and retaliation is consistent with Titles VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 34 CFR Part 106, the Ameri- cans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and 34 CFR 104.7, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, and the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act of 2008. In addition to contacting the Associate Provost for Planning and Administration, who is the compliance coordinator, persons with inquiries regarding the application of Title IX and 34 CFR Part 106 may contact the Regional Civil Rights Director, U.S. -

Master of Divinity Program

Master of Divinity Program About Our Program The Master of Divinity (M.Div) is a professional degree designed for students who already hold a bachelor’s degree and serve or desire to serve in such roles as pastor, missionary, teacher, theologian, professor, Christian counselor, chaplain, military or civilian. Students in this degree program develop competencies in Biblical Studies, Biblical Theology, Pastoral Care, Christian Counseling, Church History, Hermeneutics, and Homiletics. The curriculum is designed to be completed in three years, although many students may take longer due to family, church, and job related responsibilities. It is common for a pastor to work on his M.Div while actively pastoring a flock. Program Objectives Graduates of the Master of Divinity Program will be able to demonstrate: • Knowledge of the nature and content of the whole Bible, a working methodology for biblical study and interpretation, and a clear formulation and personal integration of the student’s own understanding of the overarching message of the Bible. • Knowledge of the central doctrines of Christianity and of the historical models that have been used to articulate and apply them. Students will be able to formulate theological and ethical concepts in light of the heritage of the whole church and to apply these concepts in contemporary life situations. • An understanding of Christian ministry founded on biblical mandates, informed by the church’s heritage and relevant to its present circumstances. • A commitment to a lifelong, intentional process -

Master of Divinity

MASTER OF DIVINITY MASTER OF DIVINITY OBJECTIVES The three-year Master of Divinity (M.Div.) degree provides a strong theological and practical foundation to those preparing for the ordained priesthood or for full-time lay ecclesial ministry in the Catholic Church. It accomplishes this goal through an integrated core curriculum designed to ensure appropriate academic, ministerial, and spiritual formation. Since leadership in ministry today requires collaboration between women and men, religious and secular, ordained and lay, M.Div. program the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry (STM) promotes collaborative learning as an appropriate means of preparing for ministry in all its forms. Building upon the previous theological and pastoral experience of the student, the program fosters the desire for lifelong learning and development in and through ministry. At the completion of this program, the student will be able to a. demonstrate a nuanced and integrated understanding of the Catholic theological tradition; b. apply the insights of the Catholic theological tradition to engage with contemporary social and religious issues; c. integrate theological thinking with ministerial practice in response to pastoral needs; d. demonstrate the competencies constitutive of effective and co-responsible ministry; and e. embody a level of human and spiritual formation that accords with the requirements for ecclesial ministry in the Catholic Church. ACADEMIC FORMATION Shaped by Boston College’s commitment to excellence, the M.Div. program supports the student's academic formation through disciplined theological study. Priests and lay ministers must be able to interpret the meaning and relevance of Christian revelation and the Church’s tradition for today’s world. -

Degree Program Requirements - Mdiv

MASTER OF DIVINITY The Master of Divinity degree is the basic graduate degree in theological education. The eighty-one hour program of study leading to this degree is designed to prepare students for various forms of ministry in the church. In recognition of the great diversity of students’ undergraduate preparation and vocational goals, the M.Div. curriculum is flexible and allows much freedom in the selection of courses. Certificates in Biblical Studies, Black Church Studies, History, Theology, and Ethics, Military Chaplaincy, Pastoral Care, and Sexual and Gender Justice are available within the structure of the program. Curriculum I. Basic Theological Studies - 57 hours Requirements for Basic Theological Studies are normally satisfied by courses in the 60003-69999 series. However, a student with a special background in a subject matter may, with approval, substitute an advanced course for a 60003-69999 series course. A. Bible - 9 hours, of which 3 must be in Hebrew Bible (HEBI 60003 Interpreting the Hebrew Bible and Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books) and 3 in New Testament (NETE 60003 Interpreting the New Testament). Once the appropriate introductory course is completed, the 3 hours of an exegesis course (650xx) may be chosen from the wide range of upper level courses in either HEBI or NETE. B. History - 6 hours: 1. CHHI 60013 History of Christianity I, Early and Medieval 2. CHHI 60023 History of Christianity II, Reformation and Modern C. Theology and Ethics - 12 hours, distributed in the following ways: 1. CHTH 60003 Introduction to Christian Theology I 2. CHTH XXXX Three additional hours chosen from specified course options. -

D. Min. Overview-CUA

DOCTOR OF MINISTRY The Catholic University of America INTRODUCTION: The Doctor of Ministry is a professional doctorate offering students advanced theological and pastoral formation for competent and effective pastoral ministry. Candidates choose from one of four concentrations: Evangelization, Liturgical Catechesis, Seminary Formation, or Spirituality. The D.Min. degree program runs once a year for fifteen weeks, between April 1 and July 15, for three consecutive years. It uses a blended learning model, thirteen weeks online and two weeks in residence on campus. The residency usually take place around the first two weeks of June and is a mandatory element of the program. Students normally take three courses each year during each fifteen-week cycle. Discussion between the inquirer and the director of the concentration area of interest is highly recommended before submitting an application to discuss the inquirer’s goals and objectives for being in a doctoral program and interests regarding the concentration area. Deadline for applications is December 1 for courses that begin the following April. It is highly recommended that the application process begin no later than September of the year preceding the first year of anticipated studies. PRE-REQUISITES: 1. Possession of a Master of Divinity degree or its educational equivalent (i.e., approximately 72 graduate level credits in theology and its related fields) with a minimum cumulative G.P.A. of 3.0. 2. A minimum of three years of full-time service in pastoral ministry or its equivalent (e.g., 6 years of half-time ministry, etc.). 3. Women and men religious, priests, deacons and seminarians must submit a letter of endorsement from their bishop or ecclesiastical superior. -

Master of Divinity (Mdiv) Degree Planner

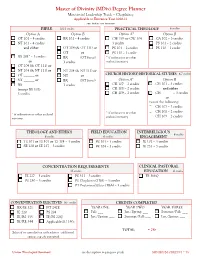

Master of Divinity (MDiv) Degree Planner Ministerial Leadership Track – Chaplaincy Applicable to Entrance Year 2020-21 see notes on reverse BIBLE 10-11 credits PRACTICAL THEOLOGY 6 credits Option A Option B Option A* Option B OT 101 – 4 credits BX 101 – 4 credits CW 103 or CW 104 CA 102 – 3 credits NT 101 – 4 credits 3 credits PS 101 – 2 credits and either OT 204 (& OT 111) or PS 101 – 2 credits PS 110 – 1 credit OT ______ or PS 110 – 1 credit BX 201* – 3 credits BX ______ (OT focus) * if ordination or other or 3 credits ecclesial ministry OT 204 (& OT 111) or NT 204 (& NT 111) or NT 204 (& NT 111) or CHURCH HISTORY/HISTORICAL STUDIES 6-7 credits OT ______ or NT ______ or NT ______ or BX ______ (NT focus) Option A* Option B BX ______ 3 credits CH 107 – 2 credits CH 101 – 3 credits (except BX 101) CH 108 – 2 credits and either 3 credits CH 109 – 2 credits CH ______ – 3 credits or two of the following: CH 107 – 2 credits CH 108 – 2 credits * if ordination or other ecclesial * if ordination or other CH 109 – 2 credits ministry ecclesial ministry THEOLOGY AND ETHICS FIELD EDUCATION INTERRELIGIOUS 6 credits 6 credits 6 credits ENGAGEMENT TS 101 or TS 103 or TS 104 – 3 credits FE 103 – 3 credits IE 102 – 3 credits SE 208 or SE 217 – 3 credits FE 104 – 3 credits IE 231 – 3 credits CONCENTRATION REQUIREMENTS CLINICAL PASTORAL 15 credits EDUCATION 6 credits IE 227 – 3 credits PS 311 – 3 credits PS 366Q PS 250 – 3 credits PS Chaplaincy (TBA) – 3 credits PT Professional Ethics (TBA) – 3 credits CONCENTRATION -

Programs of Study for Laity, Deacons and Religious

Programs of Study for Laity, Deacons and Religious NOTRE DAME SEMINARY Graduate School of Theology Our Lady’s Seminary in the 21st Century – For Priests, for the Faithful, for the World… 1 GREETINGS IN THE LORD! In decades past, some have perceived Catholic seminaries as exclusive, spiritually gated communities – only for men and only those men studying for the priesthood. Even today, many imagine the seminary as half university, half monastery, and wholly off-limits to all but a few good men. Yet this perception misses the mark. At Notre Dame Seminary our goal, guided by our Chancellor, Archbishop Gregory Aymond, is to be an apostolic community where all of God’s people—seminarians, deacons, religious and laity—are formed as closely as possible. As of this writing, 60 such students from across the region are pursuing programs of study and formation together with 125 seminarians. They pray together at daily Mass in Our Lady’s Chapel and study together in our classrooms. They share meals in our dining room and serve together in our many outreaches. Our lay students, deacons and religious are at the very heart of our seminary life, and promise a bright future of evangelization when they leave these halls to serve the Church and the world. Notre Dame Seminary is helping them become, as St. Paul called the lay people of the church of Rome, “co-workers in Christ Jesus… chosen in the Lord.” Guiding them in their prayer, study and community is one of the most talented and accomplished faculties in seminary education today. -

SAINT MARY SEMINARY and GRADUATE SCHOOL of THEOLOGY at the Center for Pastoral Leadership

SAINT MARY SEMINARY AND GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY At The Center for Pastoral Leadership Roman Catholic Diocese of Cleveland 2020-2023 Catalog I like comparing the vocation to the ordained ministry to the “treasure hidden in a field” (13:44). It is truly a treasure that God places from the beginning in the hearts of some men; those whom He has chosen and called to follow him in this special state of life. This treasure, which needs to be discovered and brought to light, is not meant to “enrich” just someone. The one called to the ministry is not the “master” of his vocation, but the administrator of a gift that God has entrusted to him for the good of all people, rather, of all men and women, including those who have distanced themselves from religious practice or do not profess faith in Christ. At the same time, the whole of the Christian community is the guardian of the treasure of these vocations, destined for His service, and it must be ever more conscious of the duty to promote them, welcome them and accompany them with affection. God never ceases to call some to follow and serve Him in the ordained ministry. We too, however, must do our part, through formation, which is the response of man, of the Church to God’s gift, that gift that God gives through vocations. It means guarding and fostering vocations, that they may bear ripe fruit. They are “diamonds in the rough” ready to be carefully polished with respect for the conscience of the candidates and with patience, so that they may shine among the People of God.