Edward Said and the Iranian Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Politics

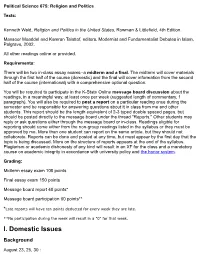

Political Science 675: Religion and Politics Texts: Kenneth Wald, Religion and Politics in the United States, Rowman & Littlefield, 4th Edition. Mansoor Moaddel and Kamran Talattof, editors, Modernist and Fundamentalist Debates in Islam, Palgrave, 2002. All other readings online or provided. Requirements: There will be two in-class essay exams--a midterm and a final. The midterm will cover materials through the first half of the course (domestic) and the final will cover information from the second half of the course (international) with a comprehensive optional question. You will be required to participate in the K-State Online message board discussion about the readings, in a meaningful way, at least once per week (suggested length of commentary, 1 paragraph). You will also be required to post a report on a particular reading once during the semester and be responsible for answering questions about it in class from me and other students. This report should be the length equivalent of 2-3 typed double spaced pages, but should be posted directly to the message board under the thread "Reports." Other students may reply or ask questions either through the message board or in-class. Readings eligible for reporting should come either from the non-group readings listed in the syllabus or they must be approved by me. More than one student can report on the same article, but they should not collaborate. Reports can be done and posted at any time, but must appear by the first day that the topic is being discussed. More on the structure of reports appears at the end of the syllabus. -

1 June 8, 2020 to Members of The

June 8, 2020 To Members of the United Nations Human Rights Council Re: Request for the Convening of a Special Session on the Escalating Situation of Police Violence and Repression of Protests in the United States Excellencies, The undersigned family members of victims of police killings and civil society organizations from around the world, call on member states of the UN Human Rights Council to urgently convene a Special Session on the situation of human rights in the United States in order to respond to the unfolding grave human rights crisis borne out of the repression of nationwide protests. The recent protests erupted on May 26 in response to the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, which was only one of a recent string of unlawful killings of unarmed Black people by police and armed white vigilantes. We are deeply concerned about the escalation in violent police responses to largely peaceful protests in the United States, which included the use of rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray and in some cases live ammunition, in violation of international standards on the use of force and management of assemblies including recent U.N. Guidance on Less Lethal Weapons. Additionally, we are greatly concerned that rather than using his position to serve as a force for calm and unity, President Trump has chosen to weaponize the tensions through his rhetoric, evidenced by his promise to seize authority from Governors who fail to take the most extreme tactics against protestors and to deploy federal armed forces against protestors (an action which would be of questionable legality). -

Rouhani: Delivering Human Rights After the Election

Rouhani: Delivering Human Rights June 2017 After the Election Iranian President’s Pathway to Fulfill His Promises Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) New York Headquarters: Tel: +1 347-689-7782 www.iranhumanrights.org Rouhani: Delivering Human Rights After the Election Copyright © Center for Human Rights in Iran Rouhani: Delivering Human Rights After the Election Rouhani’s pathway to fulfill his promises: Utilize his power, negotiate the system, hold rights violators responsible, engage and empower civil society June 2017 The re-election of President Hassan Rouhani on May 19, 2017 was due in large part to the perception by the Iranian citizenry that his government would do more to improve human rights in Iran than his rivals—an outcome clearly desired by a majority of voters. During Rouhani’s campaign rallies, not only did he make explicit references to issues of political and social freedom and promises to uphold such freedoms in his second term, his supporters also repeatedly made clear their demands for improvements in human rights. Despite Iran’s tradition of giving the incumbent a second term, Rouhani’s re-election was uncertain. Many Iranians struggling with high unemployment and other economic problems did not see any improvement in their daily lives from Rouhani’s signature achievement—the nuclear deal and easing of interna- tional sanctions. Yet even though the other candidates offered subsidies and populist proposals, and Rouhani’s economic proposals were modest, he won by a large margin—far greater than his win in 2013. In addition to his rejec- tion of populist economics, Rouhani was the only candidate that talked about human rights—and the more he focused on this issue, the more his support coalesced and strengthened. -

Turkomans Between Two Empires

TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) A Ph.D. Dissertation by RIZA YILDIRIM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara February 2008 To Sufis of Lāhijan TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by RIZA YILDIRIM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Halil Đnalcık Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

Islam and Revolution

Imam Khomeini Islam and Revolution www.islamic-sources.com ISLAM and REVOLUTION 1 2 ISLAM and REVOLUTION Writings and Declarations of Imam Khomeini Translated and Annotated by Hamid Algar Mizan Press, Berkeley Contemporary Islamic Thought, Persian Series 3 Copyright © 1981 by Mizan Press All Rights Reserved Designed by Heidi Bendorf LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Khumayni, Ruh Allah. Islam and revolution. 1. Islam and state-Iran-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Iran-Politics and government-1941-1979-Addresses, essays, lectures. 3. Shiites-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Algar, Hamid. II. Title. ISBN 0-933782-04-7 hard cover ISBN 0-933782-03-9 paperback Manufactured in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS FOREWORD 9 INTRODUCTION BY THE TRANSLATOR 13 Notes 22 I. Islamic Government 1. INTRODUCTION 27 2. THE NECESSITY FOR ISLAMIC GOVERNMENT 40 3. THE FORM OF ISLAMIC GOVERNMENT 55 4. PROGRAM FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AN ISLAMIC GOVT. 126 Notes 150 II. Speeches and Declarations A Warning to the Nation/1941 169 In Commemoration of the Martyrs at Qum/ April 3, 1963 174 The Afternoon of ‘Ashura/June 3, 1963 177 The Granting of Capitulatory Rights to the U.S./ October27, 1964 181 Open Letter to Prime Minister Hoveyda/April 16, 1967 189 Message to the Pilgrims/February 6, 1971 195 The Incompatibility of Monarchy With Islam/ October 13, 1971 200 5 Message to the Muslim Students in North America/ July 10, 1972 209 In Commemoration of the First Martyrs of the Revolution/February 19, 1978 212 Message to the People of Azerbayjan/ -

Iran 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Parliamentary elections held in 2016 and presidential elections held in 2017 were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

Not for Distribution

6 The decline of the legitimate monopoly of violence and the return of non-state warriors Cihan Tuğal Introduction For the last few decades, political sociology has focused on state-making. We are therefore quite ill equipped to understand the recent rise of non-state violence throughout the world. Even if states still seem to perform more violence than non- state actors, the latter’s actions have come to significantly transform relationships between citizens and states. Existing frameworks predispose scholars to treat non-state violence too as an instrument of state-building. However, we need to consider whether non-state violence serves other purposes as well. This chapter will first point out how the post-9/11 world problematises one of sociology’s major assumptions (the state’s monopolisation of legitimate violence). It will then trace the social prehistory of non-state political violence to highlight continui- ties with today’s intensifying religious violence. It will finally emphasise that the seemingly inevitable rise of non-state violence is inextricably tangled with the emergence of the subcontracting state. Neo-liberalisation aggravates the practico- ethical difficulties secular revolutionaries and religious radicals face (which I call ‘the Fanonite dilemma’ and ‘the Qutbi dilemma’). The monopolisation of violence: social implications War-making, military apparatuses and international military rivalry figure prominently in today’s political sociology. This came about as a reaction to the sociology and political science of the postwar era: for quite different rea- sons, both tended to ignore the influence of militaries and violence on domestic social structure. Political science unduly focused on the former and sociology on the latter, whereas (according to the new political sociology) international violence and domestic social structure are tightly linked (Mann 1986; Skocpol 1979; Tilly 1992). -

Women's Rights and Feminist Movements in Iran1

WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND FEMINIST MOVEMENTS IN IRAN1 Nayereh Tohidi • An overview of how the Iranian women’s movement • has emerged in the face of unique contexts ABSTRACT The status of women’s rights in Iran can appear contradictory at first glance – despite both high levels of education and low birth rates, for example, participation of women in the work force or in parliament is amongst the lowest in the world. In this summary of her chapter in the book Women’s Movements in the Global Era – The Power of Local Feminisms (Westview Press, 2016), Nayereh Tohidi offers a fascinating overview of women’s rights and the feminist movement in Iran. The author highlights how the demands, strategies, tactics, effectiveness and achievements of the movement have varied in accordance with socioeconomic developments, state policies, political trends, and cultural contexts at national and international levels. Tohidi suggests that this history can be roughly divided into eight periods from the era of Constitutional Revolution and constitutionalism (1905–1925) until the modern day under President Rouhani. Finally, despite various challenges, the author notes that the women’s movement in Iran continues to grow and reminds the reader of the key role that civil society plays in guaranteeing equal rights and gender justice in Iran and beyond. KEYWORDS Iran | Women’s rights | Feminism • SUR 24 - v.13 n.24 • 75 - 89 | 2016 75 WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND FEMINIST MOVEMENTS IN IRAN Women’s status and rights in contemporary Iran, and thereby the trajectory of Iranian women’s -

Revolution in Bad Times

asef bayat REVOLUTION IN BAD TIMES ack in 2011, the Arab uprisings were celebrated as world- changing events that would re-define the spirit of our political times. The astonishing spread of these mass uprisings, fol- lowed soon after by the Occupy protests, left observers in Blittle doubt that they were witnessing an unprecedented phenomenon— ‘something totally new’, ‘open-ended’, a ‘movement without a name’; revolutions that heralded a novel path to emancipation. According to Alain Badiou, Tahrir Square and all the activities which took place there—fighting, barricading, camping, debating, cooking and caring for the wounded—constituted the ‘communism of movement’; posited as an alternative to the conventional liberal-democratic or authoritar- ian state, this was a universal concept that heralded a new way of doing politics—a true revolution. For Slavoj Žižek, only these ‘totally new’ political happenings, without hegemonic organizations, charismatic leaderships or party apparatuses, could create what he called the ‘magic of Tahrir’. For Hardt and Negri, the Arab Spring, Europe’s indignado protests and Occupy Wall Street expressed the longing of the multitude for a ‘real democracy’, a different kind of polity that might supplant the hopeless liberal variety worn threadbare by corporate capitalism. These movements, in sum, represented the ‘new global revolutions’.1 ‘New’, certainly; but what does this ‘newness’ tell us about the nature of these political upheavals? What value does it attribute to them? In fact, just as these confident appraisals were being circulated in the us and Europe, the Arab protagonists themselves were anguishing about the fate of their ‘revolutions’, lamenting the dangers of conservative restora- tion or hijacking by free-riders. -

Khomeinism, the Islamic Revolution and Anti Americanism

Khomeinism, the Islamic Revolution and Anti Americanism Mohammad Rezaie Yazdi A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Political Science and International Studies University of Birmingham March 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The 1979 Islamic Revolution of Iran was based and formed upon the concept of Khomeinism, the religious, political, and social ideas of Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini. While the Iranian revolution was carried out with the slogans of independence, freedom, and Islamic Republic, Khomeini's framework gave it a specific impetus for the unity of people, religious culture, and leadership. Khomeinism was not just an effort, on a religious basis, to alter a national system. It included and was dependent upon the projection of a clash beyond a “national” struggle, including was a clash of ideology with that associated with the United States. Analysing the Iran-US relationship over the past century and Khomeini’s interpretation of it, this thesis attempts to show how the Ayatullah projected "America" versus Iranian national freedom and religious pride. -

Religious Studies Review

Religious Studies Review A Quarterly Review of Publications in the Field of Religion and Related Disciplines Volume 6, Number 2 Published by the Council on the Study of Religion April 1980 THE STUDY OF ISLAM: THE WORK OF HENRY CORBIN Hamid Algar Contents Department of Near Eastern Studies University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 REVIEW ESSAYS Orientalism—the purportedly scientific study of the reli The Study of Islam: The Work of Henry Corbin gion, history, civilization, and actuality of the Muslim peo Hamid Algar 85 ples—has recently come under increasing and often justi fied attack. A self-perpetuating tradition that has flourished incestuously, rarely open to participation by any but the "Master of the Stray Detail": Peter Brown and most assimilated and "occidentalized" Muslims, it has sig Historiography nally failed to construct a credible and comprehensive vision Patrick Henry 91 of Islam as religion or as civilization, despite vast and meritorious labor accomplished in the discovery and ac Peter Brown, The Making of Late Antiquity cumulation of factual information. Nowhere have matters Reviewer: Mary Douglas 96 stood worse than in the Orientalist study of the Islamic religion. It is scarcely an exaggeration to say that so radical is the disparity between the Islam of Orientalist description Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature and the Islam known to Muslims from belief, experience, Reviewer: William H. Austin 99 and practice that they appear to be two different phenom ena, opposed to each other or even unrelated. The reasons Douglas A. Knight (editor), Tradition and Theology in for this are numerous. The persistence of traditional the Old Testament Judeo-Christian theological animus toward Islam should Reviewer: Bernhard W. -

8 Sharia and National Law in Iran

Sharia and national law in 8 Iran1 Ziba Mir-Hosseini2 Abstract In the nineteenth century, the last of a series of tribal dynasties ruled Iran, and the Shia religious establishment had a monopoly of law, which was based on their interpretations of sharia. The twentieth century opened with the first of two successful revolu- tions. In the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911, democratic nationalists sought an end to absolute monarchy, a constitution, and the rule of law. They succeeded in laying the foundations of an independent judiciary and a parliament with legislative powers. The despotic, but modernising Pahlavi shahs (1925-1979) main- tained (though largely ignored) both the constitution and parlia- ment, curtailed the power of the Shia clergy, and put aside sharia in all areas of law apart from family law, in favour of a secular le- gal system inspired by European codes. The secularisation of society and legal reforms in the absence of democracy were major factors in the convergence of popular, na- tionalist, leftist, and Islamist opposition to Pahlavi rule, which led to the 1978-1979 Iranian Revolution under Ayatollah Khomeini. Islamist elements gained the upper hand in the new Islamic Republic. Determined to reestablish sharia as the source of law and the clergy as its official interpreters, they set about undoing the secularisation of the legal system. The new constitution at- tempted an unusual and contradictory combination of democracy and theocracy; for three decades Iran has experienced fluctua- tions, sometimes violent, between emerging democratic and plur- alistic popular movements and the dominance of theocratic des- potism.