I. a Humanist John Merbecke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

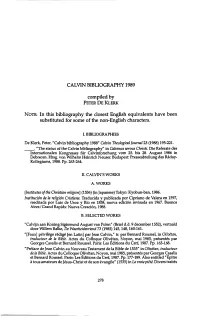

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1989 Compiled By

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1989 compiled by PETER DE KLERK NOTE: In this bibliography the closest English equivalents have been substituted for some of the non-English characters. I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1988" Calvin Theological Journal 23 (1988) 195-221. "The status of the Calvin bibliography" in Calvinus servus Christi. Die Referate des Internationalen Kongresses für Calvinforschung vom 25. bis 28. August 1986 in Debrecen. Hrsg. von Wilhelm Heinrich Neuser. Budapest: Presseabteilung des Ráday- Kollegiums, 1988. Pp. 263-264. II. CALVIN'S WORKS Α. WORKS [Institutes of the Christian religion] (1536) (in Japanese) Tokyo: Kyobun-ban, 1986. Institución de la religión Cristiana. Traducida y publicada por Cipriano de Valera en 1597, reeditada por Luis de Usoz y Río en 1858, nueva edición revisada en 1967. Buenos Aires/Grand Rapids: Nueva Creación, 1988. B. SELECTED WORKS "Calvijn aan Koning Sigismund August van Polen" (Brief d.d. 9 december 1552), vertaald door Willem Balke, De Waarheidsvriend 73 (1985) 145,148,160-161. "[Faux] privilège rédigé [en Latin] par Jean Calvin," tr. par Bernard Roussel, in Olivétan, traducteur de la Bible. Actes du Colloque Olivétan, Noyon, mai 1985, présentés par Georges Casalis et Bernard Roussel. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1987. Pp. 163-168. "Préface de Jean Calvin au Nouveau Testament de la Bible de 1535" in Olivétan, traducteur de la Bible. Actes du Colloque Olivétan, Noyon, mai 1985, présentés par Georges Casalis et Bernard Roussel. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1987. Pp. 177-189. Also entitled "Épître à tous amateurs de Jésus-Christ et de son évangile" (1535) in ha vraie piété. -

Famous Men of the Renaissance & Reformation Free

FREE FAMOUS MEN OF THE RENAISSANCE & REFORMATION PDF Robert G Shearer,Rob Shearer | 196 pages | 01 Sep 2000 | Greenleaf Press | 9781882514106 | English | United States Protestant Reformers - Wikipedia We offer thousands of quality curricula, workbooks, and references to meet your homeschooling Famous Men of the Renaissance & Reformation. To assist you in your choices, we have included the following symbol next to those materials that specifically reflect a Christian worldview. If you have any questions about specific products, our knowledgeable Homeschool Specialists will be glad to help you. What would you like to know about this Famous Men of the Renaissance & Reformation Please enter your name, your email and your question regarding the product in the fields below, and we'll answer you in the next hours. You can unsubscribe at any time. Enter email address. Welcome to Christianbook. Sign in or create an account. Search by title, catalog stockauthor, isbn, etc. Bible Sale of the Season. By: Rob ShearerCyndy Shearer. Wishlist Wishlist. More in Greenleaf Guides Series. Write a Review. Advanced Search Links. Product Close-up This product is not available for expedited shipping. Add To Cart. Famous Men of the Middle Ages. Exploring Creation with Zoology 3 Notebooking Journal. Science in the Ancient World. Softcover Text, Vol. The Magna Charta. Revised Edition. The Door in the Wall. Sword Song. Famous Men of Greece--Student's Book. Maps and additional content are included where appropriate. Perfect for oral or written work! May be used with students from 2nd grade through high school. Related Products. Robert G. Rob ShearerCyndy Shearer. Cynthia Shearer. -

The Sacred Congregation for Seminaries and Universities

English translation by Nancy E. Llewellyn of Latin original document ORDINATIONES AD CONSTITUTIONEM APOSTOLICAM “VETERUM SAPIENTIA” RITE EXSEQUENDAM (1962) by the Sacred Congregation for Seminaries and Universities. This English translation is coPyright; however, the translator hereby grants permission to download, print, share, post, distribute, quote and excerpt it, provided that no changes, alterations, or edits of any kind are made to any Part of the written text. ©2021 Nancy E. Llewellyn. All other rights reserved. THE SACRED CONGREGATION FOR SEMINARIES AND UNIVERSITIES NORMS FOR THE CORRECT IMPLEMENTATION OF THE APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION “VETERUM SAPIENTIA” The sacred Deposit of the Latin Language is a thing which even from the first centuries of the Church’s existence, the Throne of Peter has always guarded as something holy. It considers Latin an overt and beautiful sign of unity, a mighty instrument for safeguarding and spreading Christian Truth in its fullness, and for performing sacred rites. Our most Holy Father and Lord Pope John XXIII has lifted it up from neglect and contempt and firmly asserted its official, confirmed status within the Church. In a solemn ceremony on February 22, he signed with his own hand the Apostolic Constitution “Veterum Sapientia” in the Basilica of St. Peter, laying the foundations and establishing the principles by which this language, which is proper to the Church and forever bound into Her life, shall be restored to its ancient place of glory and honor. No one, least of all this Sacred Congregation, can be unaware what great and arduous effort this most noble and necessary task will require, on account of the unfortunate state of learning and of use of the Latin language today, and because of conditions existing in various places, times, and nations. -

The Musical Life and Aims of the Ordinariate of Our Lady Of

The Musical Life and Aims of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham a paper given by the Reverend Monsignor Andrew Burnham, Assistant to the Ordinary, at the Blessed John Henry Newman Institute of Liturgical Music, Birmingham. When the Holy Father visited Westminster Abbey just two years ago, his pleasure was evident as he encountered not only the splendour of the building but also its orderly musical tradition. It was an occasion in preparation for which considerable ingenuity had been expended – in that rather over-attentive way that Anglicans go about things – and, whereas you and I know that what the Pope would undoubtedly have preferred would have been the opportunity to sit in choir – on however splendid a cushion – and absorb the glory of a weekday choral evensong, what he got was something rather more bespoke. Pontiffs and prelates are never allowed to experience things as they actually are. Nonetheless, I am sure it was not lost on him that, greeted by a Latin motet written by an Irish Protestant composer, Charles Villiers Stanford, and an English anthem written by an English recusant composer, William Byrd, he was encountering a very sophisticated musical tradition. It is a tradition that has inspired not only Irish Protestants to set Latin texts, but also sceptics, devout and not so devout, to set canticles and anthems, and, in the case of Vaughan Williams, to put his innate atheism to one side and compile what remains the best of the English hymnbooks. There is a certain amount of evidence that, when the Holy See began to talk about inviting groups of Anglicans into the full communion of the Catholic Church, some in Rome expected to receive diocesan bishops, with their cathedrals, their cathedral choirs, their parish clergy, their parish churches, and the laity of the parishes. -

Some Problems in Prosody

1903·] Some Problems in Prosody. 33 ARTICLE III. SOME PROBLEMS IN PROSODY. BY PI10PlCSSOI1 R.aBUT W. KAGOUN, PR.D. IT has been shown repeatedly, in the scientific world, that theory must be supplemented by practice. In some cases, indeed, practice has succeeded in obtaining satisfac tory results after theory has failed. Deposits of Urate of Soda in the joints, caused by an excess of Uric acid in the blood, were long held to be practically insoluble, although Carbonate of Lithia was supposed to have a solvent effect upon them. The use of Tetra·Ethyl-Ammonium Hydrox ide as a medicine, to dissolve these deposits and remove the gout and rheumatism which they cause, is said to be due to some experiments made by Edison because a friend of his had the gout. Mter scientific men had decided that electric lighting could never be made sufficiently cheap to be practicable, he discovered the incandescent lamp, by continuing his experiments in spite of their ridicule.1 Two young men who "would not accept the dictum of the authorities that phosphorus ... cannot be expelled from iron ores at a high temperature, ... set to work ... to see whether the scientific world had not blundered.'" To drive the phosphorus out of low-grade ores and convert them into Bessemer steel, required a "pot-lining" capable of enduring 25000 F. The quest seemed extraordinary, to say the least; nevertheless the task was accomplished. This appears to justify the remark that "Thomas is our modem Moses";8 but, striking as the figure is, the young ICf. -

AD Times for July 11, 2019

“The Allentown Diocese in the Year of Our Lord” VOL. 31, NO. 13 JULY 11, 2019 Serrans Honor Newly Ordained as Agents of Healing and Hope By TARA CONNOLLY Staff writer “It’s a great time to be a priest – to be the one called by our Lord – to bring the light of Christ into the darkness that has clouded our Church this past year.,” said Father Thomas Bortz June 17 during the Ordinandi Dinner at St. Mary, Hamburg. “You three get to be agents of healing, figures of hope and instruments for renewal for the people of Allentown.” Father Bortz, pastor of St. Ignatius Loyola, Sinking Spring, was guest speaker at the celebration for the newly ordained priests – Father Giuseppe Esposito, Father John Maria and Father Zachary Wehr. Hosted by the Serra Clubs of the Diocese of Allentown “The greatest thing you get to do is feed District I-80, the dinner drew God’s people, and you get to feed them an estimated 200 guests and with the greatest gift ever.” priests. After thanking the Serrans for their prayers and support of seminarians and priests, Father Bortz said the “yes” of the newly ordained men was not to go to the seminary but to a calling to the priesthood of Jesus Christ. “Your formation gave you answers when God questioned your commitment, and the sacred chrism on your hands was you telling the world that you’re ‘all in,’” he said. “And nothing aggravated Satan more.” Recalling the terroristic attacks on 9/11, he told the guests that the prince of darkness directed the tragic day. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Merbecke (1510–1585) Gathering of the Community

ĎPMýIZQ[PāP]ZKP Ash Wednesday WNí \ĉ]SM 26 February 2020 We acknowledge that we meet and work in the Treaty One Land, Welcome Guests the traditional land of the Anishinaabe, Cree, and Dakota people, Newcomers are encouraged to make themselves known to the and the homeland of the Métis Nation. clergy and to phone the parish office at 204.452.3609 should you We are grateful for their stewardship of this land and their hospitality wish to express any needs or concerns. Please complete a visitor which allows us to live, work, and serve God the Creator here. leaflet or envelope with your email address if you would like to receive parish newsletters sent to you regularly. 19:30 – Sung Eucharist and Imposition of Ashes Service Music Setting: Communion Service - John Merbecke (1510–1585) Gathering of the Community Voluntary (Mr. Kinnard) Miserere mei, Deus - Gregorio Allegri (1582–1652) Hymn 67 Come down, O love divine §stand Down Ampney Greeting Priest The Lord be with you. People And with thy spirit. Let us pray. Collect for Ash Wednesday Priest Almighty and everlasting God, you despise nothing you have made and forgive the sins of all who are penitent. Create and make in us new and contrite hearts, that we, worthily lamenting our sins and acknowledging our brokenness, may obtain of you, the God of all mercy, perfect remission and forgiveness; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. Proclamation of the Word First Lesson Isaiah 58.1–12 §sit Lector A Reading from the Book of Isaiah. -

The Poetry Handbook I Read / That John Donne Must Be Taken at Speed : / Which Is All Very Well / Were It Not for the Smell / of His Feet Catechising His Creed.)

Introduction his book is for anyone who wants to read poetry with a better understanding of its craft and technique ; it is also a textbook T and crib for school and undergraduate students facing exams in practical criticism. Teaching the practical criticism of poetry at several universities, and talking to students about their previous teaching, has made me sharply aware of how little consensus there is about the subject. Some teachers do not distinguish practical critic- ism from critical theory, or regard it as a critical theory, to be taught alongside psychoanalytical, feminist, Marxist, and structuralist theor- ies ; others seem to do very little except invite discussion of ‘how it feels’ to read poem x. And as practical criticism (though not always called that) remains compulsory in most English Literature course- work and exams, at school and university, this is an unwelcome state of affairs. For students there are many consequences. Teachers at school and university may contradict one another, and too rarely put the problem of differing viewpoints and frameworks for analysis in perspective ; important aspects of the subject are omitted in the confusion, leaving otherwise more than competent students with little or no idea of what they are being asked to do. How can this be remedied without losing the richness and diversity of thought which, at its best, practical criticism can foster ? What are the basics ? How may they best be taught ? My own answer is that the basics are an understanding of and ability to judge the elements of a poet’s craft. Profoundly different as they are, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Pope, Dickinson, Eliot, Walcott, and Plath could readily converse about the techniques of which they are common masters ; few undergraduates I have encountered know much about metre beyond the terms ‘blank verse’ and ‘iambic pentameter’, much about form beyond ‘couplet’ and ‘sonnet’, or anything about rhyme more complicated than an assertion that two words do or don’t. -

The 2007 Edition Is Available in PDF Form By

VOX The new Chapter Secretary: Nick Gale [email protected] The Academy of St Cecilia Patrons: The Most Hon. The Marquess of Londonderry Dean and Education Advisor: Sir Peter Maxwell Davies CBE John McIntosh OBE Vice Patrons: James Bowman CBE, Naji Hakim, Monica Huggett [email protected] From the master Treasurer: Paula Chandler [email protected] elcome to the 2007 edition of Vox - the mouthpiece of the Academy of St Cecilia. Registrar: Jonathan Lycett We always welcome contributions from our members - [email protected] indeed without them Vox would not exist. In this edition we announce our restructured Chapter and its new members; feature a major article on Thomas Tallis Director of Communications: whose 500th anniversay falls at this time; and we Alistair Dixon review the Academy’s most major event to date, the [email protected] chant day held in June 2006. Our new address is: Composer in Residence: Nicholas O'Neill The Academy of St Cecilia Email: [email protected] C/o Music Department [email protected] Cathedral House Westminster Bridge Road Web site: LONDON SE1 7HY www.academyofsaintcecilia.com Archivist: Graham Hawkes Tel: 020 8265 6703 [email protected] ~ Page 1 ~ ~ Page 2 ~ Advisors to the Academy Thomas Tallis (c.1505 - 1585) Alistair Dixon, a member of the Chapter of the Academy, spent ten years studying and performing the music of Thomas Tallis. In 2005 Academic Advisor: he released the last in the series of recordings with his choir, Chapelle Dr Reinhard Strohm PhD (KU Berlin) FBA HonFASC. Heather Professor of Music Oxford University du Roi, of the Complete Works of Thomas Tallis in nine volumes. -

Completions and Reconstructions of Musical Works Part 1: Introduction - Renaissance Church Music and the Baroque Period by Stephen Barber

Completions and Reconstructions of Musical Works Part 1: Introduction - Renaissance Church Music and the Baroque Period by Stephen Barber Introduction Over the years a number of musical works have been left incomplete by their composers or have been partly or wholly lost and have been reconstructed. I have a particular interest in such works and now offer a preliminary survey of them. A musical work in the Western classical tradition is the realization of a written score. Improvisation usually plays a very small part, and is replaced by interpretation, which means that a score may be realized in subtly different ways. The idiom in most periods involves a certain symmetry in design and the repetition, sometimes varied, sometimes not, of key parts of the work. If the score is unfinished, then a completion or reconstruction by a good scholar or composer allows us to hear at least an approximation to what the composer intended. The use of repetition as part of the overall design can make this possible, or the existence of sketches or earlier or later versions of the work, or a good understanding of the design and idiom. Without this the work may be an incomplete torso or may be unperformable. The work is not damaged by this process, since, unlike a picture, a sculpture or a building, it exists not as a unique physical object but as a score, which can be reproduced without detriment to the original and edited and performed without affecting the original version. Completions and reconstructions may be well or badly done, but they should be judged on how well they appear to complete what appears to be the original design by the composer.