Traditions and Protocol of a Presidential Funeral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Briefsmarch 2018

CORPORATEContents BRIEFSMarch 2018 THE MONTH’S HIGHLIGHTS MINING 27 WORD FOR WORD 61 MGB team up with DOST for COMMENTARY nickel research SPECIAL REPORTS I.T. UPDATE 62 PH ranks 2nd least start-up POLITICAL friendly in Asia-Pacific 28 2017 Corruption Perceptions BUSINESS CLIMATE INDEX Index: PH drops anew CORPORATE BRIEFS 32 Sereno battles impeachment 38 in House, quo warranto in SC INFRASTRUCTURE 33 PH announces withdrawal from the ICC 75 New solar projects for Luzon 76 P94Bn infra projects in Davao Region THE ECONOMY 77 Decongesting NAIA-1 55 38 2017 budget deficit below limit on healthy government CONGRESSWATCH finances 40 More jobs created in January, 81 Senate approves First 1,000 but quality declines Days Bill Critical in Infant, 42 Exchange rate at 12-year low Child Mortality in February 82 Senate approves National ID 75 BUSINESS 84 Asia Pacific Executive Brief 102 Asia Brief contributors 55 Pledged investments in 2017, lowest in more than a decade 58 PH manufacturing growth to sustain double-digit recovery 59 PH tops 2018 Women in Business Survey 81 Online To read Philippine ANALYST online, go to wallacebusinessforum.com For information, send an email to [email protected] or [email protected] For publications, visit our website: wallacebusinessforum.com Philippine ANALYST March 2018 Philippine Consulting is our business...We tell it like it is PETER WALLACE Publisher BING ICAMINA Editor Research Staff: Rachel Rodica Christopher Miguel Saulo Allanne Mae Tiongco Robynne Ann Albaniel Production-Layout Larry Sagun Efs Salita Rose -

The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada

International Bulletin of Political Psychology Volume 5 Issue 3 Article 1 7-17-1998 From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada IBPP Editor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Editor, IBPP (1998) "From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada," International Bulletin of Political Psychology: Vol. 5 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp/vol5/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Bulletin of Political Psychology by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editor: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada International Bulletin of Political Psychology Title: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada Author: Elizabeth J. Macapagal Volume: 5 Issue: 3 Date: 1998-07-17 Keywords: Elections, Estrada, Personality, Philippines Abstract. This article was written by Ma. Elizabeth J. Macapagal of Ateneo de Manila University, Republic of the Philippines. She brings at least three sources of expertise to her topic: formal training in the social sciences, a political intuition for the telling detail, and experiential/observational acumen and tradition as the granddaughter of former Philippine president, Diosdado Macapagal. (The article has undergone minor editing by IBPP). -

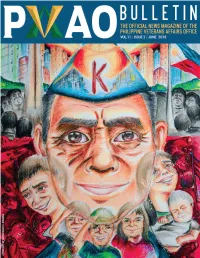

PVAO-Bulletin-VOL.11-ISSUE-2.Pdf

ABOUT THE COVER Over the years, the war becomes “ a reminder and testament that the Filipino spirit has always withstood the test of time.” The Official News Magazine of the - Sen. Panfilo “Ping” Lacson Philippine Veterans Affairs Office Special Guest and Speaker during the Review in Honor of the Veterans on 05 April 2018 Advisory Board IMAGINE A WORLD, wherein the Allied Forces in Europe and the Pacific LtGen. Ernesto G. Carolina, AFP (Ret) Administrator did not win the war. The very course of history itself, along with the essence of freedom and liberty would be devoid of the life that we so enjoy today. MGen. Raul Z. Caballes, AFP (Ret) Deputy Administrator Now, imagine at the blossoming age of your youth, you are called to arms to fight and defend your land from the threat of tyranny and oppression. Would you do it? Considering you have a whole life ahead of you, only to Contributors have it ended through the other end of a gun barrel. Are you willing to freely Atty. Rolando D. Villaflor give your life for the life of others? This was the reality of World War II. No Dr. Pilar D. Ibarra man deserves to go to war, but our forefathers did, and they did it without a MGen. Alfredo S. Cayton, Jr., AFP (Ret) moment’s notice, vouchsafing a peaceful and better world to live in for their children and their children’s children. BGen. Restituto L. Aguilar, AFP (Ret) Col. Agerico G. Amagna III, PAF (Ret) WWII Veteran Manuel R. Pamaran The cover for this Bulletin was inspired by Shena Rain Libranda’s painting, Liza T. -

List of PO for the Year 2015 PO Status PO Amount

List of PO for the Year 2015 PO No. PO Date PR number PR Mode PR OCode PO Purpose Supplier Name PO Amount PO Status 1 CN 25-Feb-15 14-04-0651 PUBLIC BIDDING MIS For OP Firewall & Security Upgrade NERA (Philippines) Inc. 1,815,208.38 PO Released to COA 15-0080 Stage 5 2 15-0016 12-Jan-15 14-04-0666 NEGOTIATED - 1 Engineering For the repair of & Resanding of Narra Floor @ DES-IS-IT 556,000.00 PO Released to COA Malacañang Palace ENTERPRISES Stage 5 3 15-0036 30-Jan-15 14-05-0868 PUBLIC BIDDING Engineering For the Rehabilitation of 20TR AHU No. 11 DES-IS-IT 1,109,080.38 PO Released to COA serving the Executive Secretary's Staff Office at ENTERPRISES Stage 5 the Roof Deck of AHU Machine Room 4 15-0039 4-Feb-15 14-05-0906 PUBLIC BIDDING Protocol Will be used in the visit to the Philippines of ELLITE ADS 664,475.84 PO Released to COA the Heads of State/Government on July to CORPORATION Stage 5 December 2014 5 CN 20-May-15 14-05-0924 PUBLIC BIDDING PAW Repair of B412 # 1998 assigned with 250th BET SHEMESH 107,770,000.00 PO Released to COA 2015-0255 PAW ENGINES LTD Stage 5 6 CN 25-Feb-15 14-06-0977 NEGOTIATED - 1 MIS For upgrading of OP Network System for NERA (Philippines) Inc. 500,000.00 PO Released to COA 15-0081 security purposes Stage 5 7 CN 4-May-15 14-06-0981 PUBLIC BIDDING Engineering For the rehabilitation of the Gynmasium, Area MARCPHIL 9,510,000.00 PO Released to COA 2015-0229 III, Malacanang Park CONSTRUCTION Stage 5 8 15-0160 14-Apr-15 14-06-1097 PUBLIC BIDDING PCTC 1 lot IT equipment for the installation of Interpol LOE COMPUTER & 1,058,310.40 PO Released to COA interconnectivity communications sytem ACCESSORIES Stage 5 9 CN 27-Feb-15 14-07-1314 PUBLIC BIDDING Engineering For the replacement of unserviceable 500TR AIRCODE 20,736,548.00 PO Released to COA 15-0079 Centrifugal Chiller 1 including valves, pipes, CORPORATION Stage 5 fittings electrical controls, etc. -

Pepper Anthracnose in the Philippines: Knowledge Review and Molecular Detection of Colletotrichum Acutatum Sensu Lato

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 July 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202007.0355.v1 Pepper anthracnose in the Philippines: knowledge review and molecular detection of Colletotrichum acutatum sensu lato Mark Angelo Balendres* and Fe Dela Cueva Institute of Plant Breeding, College of Agriculture and Food Science, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines 4031 * Corresponding Author: M. A. Balendres ([email protected]) Abstract This paper reviews the current knowledge of pepper anthracnose in the Philippines. We present research outputs on pepper anthracnose from the last three years. Then, we present evidence of the widespread occurrence of C. acutatum sensu lato in the Philippines. Finally, we highlight some research prospects that would contribute towards developing an integrated anthracnose management program. Keywords: Colletotrichum truncatum, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, chilli anthracnose, polymerase chain reaction assay, disease distribution I. Knowledge review of pepper anthracnose in the Philippines Pepper in the Philippines Pepper (Capsicum sp.) is an important vegetable crop in the family Solanaceae. It is mainly added as a spice or condiment in various dishes. In the Philippines, there is a demand for pepper in both the fresh and processing markets. However, it is a relatively small industry compared to other vegetable crops, e.g., tomato. The Cordillera and Northern Mindanao regions produce the most but, other areas, e.g., in the CALABARZON and Central Luzon, also steadily produce pepper. The price of pepper can reach to as high as Php1,000 per Kg (USD 20), making pepper cultivation attractive to small-scale growers as a source of income. Within three months, depending on the pepper variety, growers can start harvesting the fruits, that could last to several priming’s (harvests). -

November–December 2018

NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2018 FROM THE CHAIRMAN’S DESK CAV JAIME S DE LOS SANTOS ‘69 Values that Define Organizational Stability The year is about to end. In a few months which will culminate Magnanimity – Being forgiving, being generous, being in the general alumni homecoming on February 16, 2019, a new charitable, the ability to rise above pettiness, being noble. What a leadership will take over the reins of PMAAAI. This year has been a nice thing to be. Let us temper our greed and ego. Cavaliers are very challenging year. It was a wake-up call. Slowly and cautiously blessed with intellect and the best of character. There is no need to we realized the need to make our organization more responsive, be boastful and self-conceited. relevant and credible. We look forward to new opportunities and Gratitude – The thankful appreciation for favors received and not be stymied by past events. According to Agathon as early as the bigness of heart to extend same to those who are in need. Let 400BC wrote that “Even God cannot change the past”. Paule-Enrile us perpetuate this value because it will act as a multiplier to our Borduas, another man of letters quipped that “the past must no causes and advocacies. longer be used as an anvil for beating out the present and the Loyalty - Loyalty suffered the most terrible beating among the future.” virtues. There was a time when being loyal, or being a loyalist, is George Bernard Shaw, a great playwright and political activist like being the scum of the earth, the flea of the dog that must be once said, “Progress is impossible without change, and those who mercilessly crashed and trashed. -

List of Participating Stations for the Petron Ultimate Driving Collection Promo (October 27-31, 2020)

List of Participating Stations for the Petron Ultimate Driving Collection Promo (October 27-31, 2020) REGION CITY ADDRESS 1 VISAYAS MANDAUE H. ABELLANA ST. NATIONAL HIGHWAY MANDAUE CITY, CEBU 2 VISAYAS CEBU CITY S.OSMENA BLVD., TEJERO CEBU CITY, CEBU 3 VISAYAS CEBU CITY ARCHBISHOP REYES AVE. JUAN LUNA COR CEBU CITY 4 VISAYAS CEBU CITY B. RODRIGUEZ STREET, BO. CAPITOL CEBU CITY, CEBU 5 VISAYAS CEBU CITY V. RAMA AVENUE, GUADALUPE CEBU CITY, CEBU 6 MINDANAO DAVAO MAGYSAYSAY AVE. COR GUERRERO ST DAVAO CITY, DAVAO DEL SUR 7 MINDANAO DAVAO NATIONAL HIGHWAY, TIBUNGCO DAVAO CITY, DAVAO DEL SUR 8 MINDANAO DAVAO KM. 5 BUHANGIN DAVAO CITY, DAVAO DEL SUR 9 MINDANAO DAVAO NAT'L. H-WAY , BANGKAL DAVAO CITY, DAVAO DEL SUR 10 MINDANAO DAVAO MC ARTHUR HIGHWAY, MATINA DAVAO CITY, DAVAO DEL SUR 11 MINDANAO DAVAO NATIONA'L H-WAY, ULAS DAVAO CITY, DAVAO DEL SUR 12 MINDANAO DAVAO MC ARTHUR HIGHWAY, MATINA DAVAO CITY, DAVAO DEL SUR 13 MINDANAO GENERAL SANTOS NATIONAL HIGHWAY BRGY.NORTH GENERAL SANTOS CITY, SOUTH COTABATO 14 MINDANAO GENERAL SANTOS J. CATOLICO AVENUE, BRGY. LAGAO GENERAL SANTOS CITY, SOUTH COTABATO 15 MINDANAO GENERAL SANTOS CALUMPANG GENERAL SANTOS CITY, SOUTH COTABATO List of Participating Stations for the Petron Ultimate Driving Collection Promo (October 15-31, 2020) REGION CITY ADDRESS 1 NORTH LUZON DAGUPAN LUCAO DISTRICT, DAGUPAN CITY PANGASINAN (NEAR CALACSIAO DAGUPAN DIVERSION ROAD) 2 NORTH LUZON NUEVA ECIJA IDDS-BELENA ALEXANDER (NEAR MCDONALD'S) 3 NORTH LUZON NUEVA ECIJA MAHARLIKA HIGHWAY, CAANAWAN SAN JOSE CITY, NUEVA ECIJA (NEAR MAX's -

Camillians Launch Lingap Batangas

PHILIPPINE PROVINCE NEWSLETTER January–February 2020 • Volume 20 • Number 1 CAMUP CAMILLIAN UPDATE Camillians Launch Lingap Batangas Last January 16 and 18, 2020, they held relief opera- tions by delivering goods to the Lipa Archdiocesan Social Action Commission (LASAC), ensuring that all donations reach the evacuees. Land Radio Communication Assis- tance (LARCOM), one of the Camillians’ collaborators, transported the donated goods. On January 24, 2020, Lingap Batangas formed its Core Group that will spearhead the series of health inter- ventions in the different evacuation centers. The group will also facilitate and coordinate with different helping agencies to have a common health intervention package for all evacuation centers. o better serve our fellowmen who were affected Simultaneous medical missions with spiritual accom- and displaced by Taal Volcano’s phreatic eruption paniment, psychological intervention, and food and non- last January 12, 2020, the Camillians, through the food provisions were given on January 30, 2020 to three TCamillian Task Force (CTF) and Camillian Philanthropic least served evacuation centers in Barangays Dao, Santol and Health Development Office (CPHDO), and in collab- and Gimalas in the town of Balayan, Batangas. oration with the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the The Lingap Batangas team and volunteers served Philippines-Episcopal Commission on Health Care (CBCP- more than 400 individuals (medically) and more than 100 ECHC) launched Lingap Batangas. children were given psychological first-aid (PFA). (continued on page 8) SHEPHERD’S CARE PROVINCIAL’S CORNER Fr. Jose P. Eloja, MI Lent: A Call to Repentance et even now—oracle of the Lord—return to me with your whole heart, with fasting, weeping, and mourning. -

CHAPTER 1: the Envisioned City of Quezon

CHAPTER 1: The Envisioned City of Quezon 1.1 THE ENVISIONED CITY OF QUEZON Quezon City was conceived in a vision of a man incomparable - the late President Manuel Luis Quezon – who dreamt of a central place that will house the country’s highest governing body and will provide low-cost and decent housing for the less privileged sector of the society. He envisioned the growth and development of a city where the common man can live with dignity “I dream of a capital city that, politically shall be the seat of the national government; aesthetically the showplace of the nation--- a place that thousands of people will come and visit as the epitome of culture and spirit of the country; socially a dignified concentration of human life, aspirations and endeavors and achievements; and economically as a productive, self-contained community.” --- President Manuel L. Quezon Equally inspired by this noble quest for a new metropolis, the National Assembly moved for the creation of this new city. The first bill was filed by Assemblyman Ramon P. Mitra with the new city proposed to be named as “Balintawak City”. The proposed name was later amended on the motion of Assemblymen Narciso Ramos and Eugenio Perez, both of Pangasinan to “Quezon City”. 1.2 THE CREATION OF QUEZON CITY On September 28, 1939 the National Assembly approved Bill No. 1206 as Commonwealth Act No. 502, otherwise known as the Charter of Quezon City. Signed by President Quezon on October 12, 1939, the law defined the boundaries of the city and gave it an area of 7,000 hectares carved out of the towns of Caloocan, San Juan, Marikina, Pasig, and Mandaluyong, all in Rizal Province. -

Baguio City Is Geographically Located Within Benguet—The City’S Capital

SUMMER CAPITAL OF THE PHILIPPINES B A G U I O SOTOGRANDE BAGUIO RESIDENTIAL TOWER 2 Baguio City is geographically located within Benguet—the city’s capital. Located approximately 4,810 feet (1,470 meters) above sea level within the Cordillera Central mountain range in Northern Luzon. The City’s main attraction is still its natural bounties of cool climate, panoramic vistas, pine forests and generally clean environs. It boasts of 5 forest reserves with a total area of 434.77 hectares. Three of these areas are watersheds that serve as sources of the City’s water supply. http://www.baguio.gov.ph/about-baguio-city Baguio is 8 degrees cooler on the average than any place in lowlands. When Manila sweats at 35 degrees centigrade or above, Baguio seldom exceeds 26 degrees centigrade at its warmest. LTS NO. 034771 Sotogrande Baguio Residential Tower 2 (Hotel and Residences) is the second prime development by Sta. Lucia Land, Inc. (SLLI) to rise in the City of Pines – Baguio City. It has two connecting towers, both are 8-storey high. PROJECT LOCATION SOTOGRANDE Sotogrande Baguio Hotel and Residences BAGUIO is located in Leonard Wood Rd., Baguio City,Benguet, Philippines WHY SOTOGRANDE BAGUIO PRIME LOCATION Baguio City is situated in the mountainous area of Northern Luzon, and known as the Summer Capital of the Philippines due to its cool climate with average temperature ranging from 18°C - 21°C. For a tropical country like the Philippines, Baguio City is the perfect refuge from the scorching heat in the lowland areas. It’s also famous for being the country’s City of Pines because of the amount of mossy plants, orchids, and pine trees growing in the area. -

Typhoons and Floods, Manila and the Provinces, and the Marcos Years 台風と水害、マニラと地方〜 マ ルコス政権二〇年の物語

The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Volume 11 | Issue 43 | Number 3 | Oct 21, 2013 A Tale of Two Decades: Typhoons and Floods, Manila and the Provinces, and the Marcos Years 台風と水害、マニラと地方〜 マ ルコス政権二〇年の物語 James F. Warren The typhoons and floods that occurred in the Marcos years were labelled ‘natural disasters’ Background: Meteorology by the authorities in Manila. But in fact, it would have been more appropriate to label In the second half of the twentieth century, them un-natural, or man-made disasters typhoon-triggered floods affected all sectors of because of the nature of politics in those society in the Philippines, but none more so unsettling years. The typhoons and floods of than the urban poor, particularly theesteros - the 1970s and 1980s, which took a huge toll in dwellers or shanty-town inhabitants, residing in lives and left behind an enormous trail of the low-lying locales of Manila and a number of physical destruction and other impacts after other cities on Luzon and the Visayas. The the waters receded, were caused as much by growing number of post-war urban poor in the interactive nature of politics with the Manila, Cebu City and elsewhere, was largely environment, as by geography and the due to the policy repercussions of rapid typhoons per se, as the principal cause of economic growth and impoverishment under natural calamity. The increasingly variable 1 the military-led Marcos regime. At this time in nature of the weather and climate was a the early 1970s, rural poverty andcatalyst, but not the sole determinant of the environmental devastation increased rapidly, destruction and hidden hazards that could and on a hitherto unknown scale in the linger for years in the aftermath of the Philippines. -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map JEEP Progreso 2, Makati City, Manila →Tejeron, Makati View In Website Mode City, Manila The JEEP bus line (Progreso 2, Makati City, Manila →Tejeron, Makati City, Manila) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Progreso 2, Makati City, Manila →Tejeron, Makati City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Tejeron, Makati City, Manila →Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue, Makati City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Progreso 2, Makati City, JEEP bus Time Schedule Manila →Tejeron, Makati City, Manila Progreso 2, Makati City, Manila →Tejeron, Makati City, 14 stops Manila Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Progreso 2, Makati City, Manila Bernardino, Philippines Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Dr Jose P. Rizal Ave, Makati City, Manila Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM J. P. Rizal Avenue, Philippines Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Dr Jose P. Rizal Ave, Makati City, Manila Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Estrella-Pantaleon Bridge, Philippines Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Water Front Dr / Dr Jose P. Rizal Ave Intersection, Makati City, Manila 1077 J. P. Rizal, Philippines J.P. Rizal Ave / A. Mabini Intersection, Makati City, JEEP bus Info Manila Direction: Progreso 2, Makati City, Manila →Tejeron, 3299 A. Mabini cor Zamora, Philippines Makati City, Manila Stops: 14 J.P.