Introductions to Heritage Assets: Mills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generate Your Own Hydropower

Generate Your Own Hydropower Objectives The student will do the following: 1 Build a water wheel. 2 Build a simple galvanometer. 3. Build a simple hydropower generator 4. Detect the electricity generated 5 Demonstrate how water power is converted to electricity. Subjects: Advanced General Science, Physical Science, Physics Time: 1-2 class periods if working in groups of four; 2-3 class periods if working in groups of two Materials: (for each group) compass, 2 alligator clips (optional), small spool magnetic wire (#28 or finer, insulated), 2 cardboard or masonite rectangles (about 5” x7”), glue, (2) 1-inch nails, (2) 3-inch nails, 1-inch bar magnet, (2) 1- 1/2”x4” metal strips cut from tin can, electrical tape, germanium diode (for example, type1N34A), soldering iron (optional), solder (optional), 3x5” wood block, round tinker toy. (8) 3” tinker toy spokes, 8 small paper cups, student sheets (included) Background Information The model hydropower generator made in this activity works much like hydropower plants for generating electricity. When the propeller (water wheel or turbine) spins, the magnet whizzing past the nail head generates a tiny amount of alternating current (AC) in the coil wound around the nail. The small germanium diode connected across the two nail terminals converts the AC into DC (direct current). The galvanometer will indicate that a small current has been produced by the generator. Procedure I The day before the activity is to be done, introduce it to the class A Define and describe a turbine A turbine is a device that has a central drive shaft fitted with curved vanes or blades that cause it to whirl when force is exerted upon it by water, steam, or gas. -

THE ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION Qadar Bakhsh Baloch

Qadar Bakhsh Baloch The Dialogue THE ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION Qadar Bakhsh Baloch “Thus we have appointed you a mid-most nation, that you may be witnesses upon mankind.” (Quran, 11:43) ISLAM WAS DESTINED to be a world religion and a civilisation, stretched from one end of the globe to the other. The early Muslim caliphates (empires), first the Arabs, then the Persians and later the Turks set about to create classical Islamic civilisation. In the 13th century, both Africa and India became great centres of Islamic civilisation. Soon after, Muslim kingdoms were established in the Malay-Indonesian world, while Muslims flourished equally in China. Islamic civilisation is committed to two basic principles: oneness of God and oneness of humanity. Islam does not allow any racial, linguistic or ethnic discrimination; it stands for universal humanism. Besides Islam have some peculiar features that distinguish it form other cotemporary civilisations. SALIENT FEATURES OF ISLAMIC CIVILISATION MAIN CHARACTERISTICS that distinguish Islamic civilisation from other civilisations and give it a unique position can be discerned as: • It is based on the Islamic faith. It is monotheistic, based on the belief in the oneness of the Almighty Allah, the Creator of this universe. It is characterised by submission to the will God and service to humankind. It is a socio-moral and metaphysical view of the world, which has indeed contributed immensely to the rise and richness of this civilisation. The author is a Ph. D. Research Scholar, Department of International Relations, University of Peshawar, N.W.F.P. Pakistan, the Additional Registrar of Qurtuba University and Editor of The Dialogue. -

In and Around the Watermill

In and around the watermill Our beautiful and historic watermill stands beside the River Rosaro in the small village of Posara. Peaceful and secluded, yet part of the village, the mill is just a mile or so from the walled medieval town of Fivizzano with its cafés, restaurants and shops. This is the heart of Lunigiana, in the North-west of Tuscany, a truly unspoilt part of Italy. Set in a gentle valley with mountain peaks in the background, the mill is a peaceful spot, surrounded by the National Park of the Tuscan-Emilian Appennines and The Regional Pak of the Apuan Alps, home of the marble mountains of Carrara. The Watermill is a complex of elegant and historic Tuscan buildings, around a sunny courtyard with an adjoining vine verandah, rose pergola and sun-filled walled garden. More gardens lead to walks along the river and the sun-dappled millstream. We have lovingly restored the historic buildings and created eight beautiful bedrooms with en suite bathrooms, plus two self-contained apartment suites, each with a double bedroom, bathroom and sitting room, ideal for couple or friends sharing. The bright and airy rooms are well decorated and tastefully furnished. Many contain original artworks and all enjoy lovely views of the river, the gardens or the mountains. Our graceful communal Sitting Room, with its gallery of paintings by our inspiring tutors, is ideal for post-prandial conversation and digestivi. Our courtyard dining room is the unique setting for leisurely breakfasts and mouth-watering evening meals. There is also a communal kitchen, with chilled water and facilities for personal tea-/coffee-making. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

The Impact of Lester Pelton's Water Wheel on the Development Of

VOLUME XXXVIII, NUMBER 3 SUMMER/FALL 2010 A Publication of the Sierra County Historical Society The Impact of Lester Pelton’s Water Wheel On the Development of California Rivals the 49ers! hile hordes of gold-seeking 49ers At the time, steam engines were being W swarmed into the Sierras in search used to provide power to operate the mines of their fortunes, Lester Pelton, a farmer’s but they were expensive to purchase, not son living in Ohio, came to California in easily transported, and consumed enormous W1850 with ambitions amounts of wood resulting that didn’t include gold in forested hillsides mining. He tried making becoming barren in a very money as a fisherman short time. Water wheels in Sacramento before were being tried by some coming to Camptonville mine owners making use after hearing of the gold of the enormous power strike on the north fork available from water in of the Yuba River. Still the mountain regions but not interested in being they were patterned after a miner, Pelton instead water wheels used to power spent his time observing grain mills in the East and the mining operations in Midwest and were not the Camptonville area capable of producing the and noted that both kinds amount of power needed to of mining, placer and operate hoisting equipment hard rock, required large Lester Pelton, whose invention paved the or stamp mills. amounts of power. He way for low-cost hydro-electric power Having never developed realized that hard rock an interest in mining, mining was more difficult to provide because Pelton spent many years doing carpentry power was needed to operate the hoists to and millwrighting, building many homes, a lower men into the mine shafts, bring up schoolhouse, and stamp mills driven by water loaded ore cars, and return the men to the wheels. -

UKRAINIAN FOOD JOURNAL 2016 V.5 Is.3.Pdf

ISSN 2313–5891 (Online) ISSN 2304–974X (Print) Ukrainian Food Journal Volume 5, Issue 3 2016 Kyiv Kиїв 2016 Ukrainian Food Journal is an Ukrainian Food Journal – міжнародне international scientific journal that наукове періодичне видання для publishes innovative papers of expert in the публікації результатів досліджень fields of food science, engineering and фахівців у галузі харчової науки, техніки technology, chemistry, economics and та технології, хімії, економіки і management. управління. The advantage of research results Перевага в публікації результатів publication available to students, graduate досліджень надається студентам, students, young scientists. аспірантам та молодим вченим. Ukrainian Food Journal is abstracted and Ukrainian Food Journal індексується indexed by scientometric databases: наукометричними базами: Index Copernicus (2012) EBSCO (2013) Google Scholar (2013) UlrichsWeb (2013) Global Impact Factor (2014) CABI full text (2014) Online Library of University of Southern Denmark (2014) Directory of Research Journals Indexing (DRJI) (2014) Universal Impact Factor (2014) Directory of Open Access scholarly Resources (ROAD) (2014) European Reference Index for the Humanities and the Social Sciences (ERIH PLUS) (2014) Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) (2015) InfoBase Index (2015) Chemical Abstracts Service Source Index (CASSI) (2016) Ukrainian Food Journal включено у перелік наукових фахових видань України з технічних наук, в якому можуть публікуватися результати дисертаційних робіт на здобуття наукових ступенів доктора і кандидата наук (Наказ Міністерства освіти і науки України № 1609 від 21.11.2013) Editorial office address: Адреса редакції: National University Національний університет of Food Technologies харчових технологій Volodymyrska str., 68 вул. Володимирська, 68 Ukraine, Kyiv 01601 Київ 01601 e-mail: [email protected] Scientific Council of the National Рекомендовано вченою радою University of Food Technologies Національного університету recommends the journal for printing. -

Developments in Permanent Stainless Steel Cathodes Within the Copper Industry

DEVELOPMENTS IN PERMANENT STAINLESS STEEL CATHODES WITHIN THE COPPER INDUSTRY K.L. Eastwood and G.W. Whebell Xstrata Technology Hunter Street Townsville, Australia 4811 [email protected] ABSTRACT The ISA PROCESS™ cathode plate is characterised by its copper coated suspension bar, coupled with a blade employing austenitic stainless steel alloy 316L. The blade material has become the mainstay of the technology and has been closely copied by competing cathode designs. Improvement to the cathode plate design remains a key area for research, and ongoing developments by Xstrata Technology’s ISA PROCESS™ have recently been commercialised. Two such developments are the ISA Cathode BR™ and ISA 2000 AB Cathode. The ISA BR cathode is a lower resistance cathode that has proven to enhance operating efficiencies. The AB cathode was designed to improve stripping inefficiencies in the ISA 2000 technology. These developments have now had time to mature and their long term performance will be discussed. Rising material costs and the desire to extend the operating boundaries of the standard 316L cathode plate has triggered a number of significant advances. These involve the use of different stainless steels as alternatives in some operational situations. The technical aspects and results of commercial trials on this development will also be discussed in this paper. INTRODUCTION The introduction of permanent stainless steel cathode technology was pioneered in the copper industry by IJ Perry and colleagues in 1978, with the introduction of the ISA PROCESSTM in the Townsville Copper Refinery, Perry [1]. While a number of parallel processes have emerged since its introduction, ISA Process Technology (IPT) has continued to be the mainstay electrolytic copper process with consistent improvements and superior operational performance. -

Judges List 2020 For

Suffolk Horse Society Judge List 2020 Turnout Judges - Suffolk Horse Society 2020 Home Telephone Length of Title First Name Surname Address Address 2 Town County Post Code number Telephone Email Addres Area service Mr David Curtis Hale Fen Farm 16 Hale Fen Littleport Ely CB6 1EL 07752066619 [email protected] Cambridgeshire * Mr Owen Garner Hales Farm Green Street Willingham Cambs CB4 5LB 01954 261475 [email protected] Cambridgeshire 2018 * Mr Jonathan Purse Mill Drove Farm Mill Drove Soham Cambs CB7 5HX 01353 720379 07788101305 [email protected] Cambridgeshire 2009 * Mr Malcolm Scurrell 4 Birdbush Park Ludwell Shaftesbury Dorset SP7 9NH 01747 828037 01747 828037 [email protected] Dorset Over 15 years * Mr John Peacock Ashdene, East Hannigfield Road Howe Green Chelmsford Essex CM2 7 TP 07831 384307 [email protected] Essex Over 15 years Mr Paul Mills Barratts Farm, East Lane Dedham Colchester Essex CO7 6BE 01206 323645 [email protected] Essex 2013 Miss Susan Wager Saltcote Hall, Goldhanger Road Heybridge Maldon Essex CM9 7QX 01621 853252 [email protected] Essex Over 15 years Mr Stephen Smith Leylandii Bell Farm Lane, Minster on Sea Isle of Sheppy Kent ME12 4JB 07947 951705 no email address Kent Mr Matthew Burks Roseisle Farm, West Fen Drainside Frithville Boston Lincolnshire PE22 7EU 07506 402779 [email protected] Lincolnshire 2018 * Mr Peter Crockford 201 North Road Gedney Hill Spalding Linconshire PE12 ONU 07867 977864 [email protected] Lincolnshire Over 15 years * Mr Michael L -

Flow Rate Equation for Suppressed and Submerged Sluice Gates ITRC Report No

Flow Rate Equation for Suppressed and Submerged Sluice Gates www.itrc.org/reports/sluicegate.htm ITRC Report No. R 20-001 Flow Rate Equation for Suppressed and Submerged Sluice Gates Prepared by Charles M. Burt Albert J. Clemmens Kyle Feist May 2020 IRRIGATION TRAINING & RESEARCH CENTER California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407-0730 Office Phone: (805) 756-2434 FAX: (805) 756-2433 www.itrc.org Reference to any specific process, product or service by manufacturer, trade name, trademark or otherwise does not necessarily imply endorsement or recommendation of use by either California Polytechnic State University, the Irrigation Training & Research Center, or any other party mentioned in this document. No party makes any warranty, express or implied and assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of any apparatus, product, process or data described. This report was prepared by ITRC as an account of work done to date. All designs and cost estimates are subject to final confirmation. Flow Rate Equation for Suppressed and Submerged Sluice Gates www.itrc.org/reports/sluicegate.htm ITRC Report No. R 20-001 Acknowledgements This work was funded by the California Dept. of Water Resources (Agreement No. 4600011908) and the USBR Mid-Pacific Region. Notation The following symbols are used in this report: a = relative gate opening; B = horizontal dimension of the rectangular sluice gate opening; Cc = a dimensionless contraction coefficient equaling the ratio of the area of the vena contracta -

Choosing & Using a Milling Machine

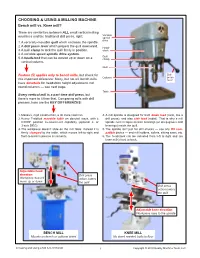

CHOOSING & USING A MILLING MACHINE Bench mill vs. Knee mill? There are similarities between ALL small vertical milling Variable machines and the traditional drill press, right: speed drive 1. A vertically-movable quill which encloses the spindle. 2. A drill press lever which propels the quill downward. Head- 3. A quill clamp to lock the quill firmly in position. stock 4. A variable-speed spindle drive system. Quill 5. A headstock that can be moved up or down on a clamp vertical column. Quill Feature (5) applies only to bench mills, but check for Drill Column press this important difference: Many, but not all, bench mills lever have dovetails for headstock height adjustment, not round columns — see next page. Table Every vertical mill is a part-time drill press, but there’s more to it than that. Comparing mills with drill presses, here are the KEY DIFFERENCES: 1. Massive, rigid construction, a lot more cast iron. 4. A mill spindle is designed for both down load (axial, like a 2. Heavy T-slotted movable table on dovetail ways, with ± drill press), and also side load (radial). That is why a mill 0.0005″ position measurement capability (optional 2- or spindle runs in tapered roller bearings (or deep-groove ball 3-axis DRO). bearings) inside the quill. 3. The workpiece doesn’t slide on the mill table: instead it is 5. The spindle isn’t just for drill chucks — use any R8 com- firmly clamped to the table, which moves left-to-right and patible device — end mill holders, collets, slitting saws, etc. -

The Mechanical Advantage (MA) of the Lever Is Defined As: Effort Arm / Load Arm = D2 / D1

ARIZONA SCIENCE LAB 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 1 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 2 Arizona Science Lab: WORKING WITH WATERWHEELS Harnessing the Energy of Water! Institute Of Electrical And Electronic Engineers, Phoenix Section Teacher In Service Program / Engineers In The Classroom (TISP/EIC) “Helping Students Transfer What Is Learned In The Classroom To The World Beyond” Our Sponsors The AZ Science Lab is supported through very generous donations from corporations, non- profit organizations, and individuals, including: 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 4 Information Sources • For more information on renewable energy, waterwheels, simple machines, and related topics: • www.Wikipedia.com • www.mikids.com/Smachines.htm • www.waterhistory.org • www.youtube.com 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 5 Norias of Hama, Syria Orontes river ~ 400AD 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 6 The Science and Engineering of Waterwheels • History – Waterwheels date back to 400 AD! • Energy – Rivers: Kinetic and Potential Energy • Simple Machines – The Power of Leverage • Using Our Science Knowledge: Build a Waterwheel! • Today: Capturing the River – Hydroelectric Power 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 7 ENERGY What is it? Energy is the ability to do work. Can you name some common forms of energy? 8 AZ Science Lab 11/29/17 V40 What is Energy? Energy is the ability to do work The food we eat contains energy. We use that energy to work and play. Energy can be found in many forms: Chemical energy ElectricalMechanical energy Energy Thermal (heat) energy 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 9 Mechanical Energy has two forms: Potential Energy (P.E.) – Stored Energy, The Energy of Position (gravitational) Kinetic Energy (K.E.) – Active Energy, The Energy of Motion (motion of waves, electrons, atoms, molecules, and substances) 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 10 Potential Energy – P.E. -

THE NEW KEENE ROCK CRUSHERS ROLLER MILL Produc T Report

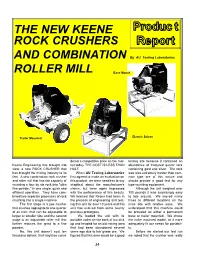

THE NEW KEENE Produc t ROCK CRUSHERS Report AND COMBINATION By AU Testing Laboratories ROLLER MILL Base Mount Trailer Mounted Electric Driven dered a competitive price on the mar- testing site because it contained an Keene Engineering has brought into ket today. THE COST IS LESS THAN abundance of fractured quartz rock view, a new ROCK CRUSHER that HALF. containing gold and silver. The rock has brought the mining industry to its When AU Testing Laboratories was also extremely harder than com- feet. A new combination rock crusher first agreed to make an evaluation on mon type ore of this nature and and roller mill that has the capacity of this product, we were needless to say should provide a good test for any crushing a four by six rock into "ultra skeptical about the manufacturer's type crushing equipment. fine powder," in one single, quick and claims, but were again impressed Although the unit weighed over efficient operation. They have com- with the performance of this beauty. 700 pounds it was surprisingly easy bined two separate processes of rock We learned that Keene had been in to tote around. We moved many crushing into a single machine. the process of engineering and test- times to different locations on the The first stage is a jaw crusher ing this unit for over 10 years and this mine site with relative ease. We that crushes aggregate to one quarter unit has evolved from some twenty understood that this machine could of an inch, that can be adjustable to previous prototypes. be provided on either a permanent larger or smaller size and the second We loaded the unit with its base or trailer mounted.