SIMPLE CURVE FORMULAS the Following Formulas Are Used in the M= R (L-Cos ½ I) Computation of a Simple Curve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Spiral Transition Curves As Related to the Visual Quality of Highway Alignment

A STUDY OF SPIRAL TRANSITION CURVES AS RELA'^^ED TO THE VISUAL QUALITY OF HIGHWAY ALIGNMENT JERRY SHELDON MURPHY B, S., Kansas State University, 1968 A MJvSTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Civil Engineering KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1969 Approved by P^ajQT Professor TV- / / ^ / TABLE OF CONTENTS <2, 2^ INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE SEARCH 3 PURPOSE 5 SCOPE 6 • METHOD OF SOLUTION 7 RESULTS 18 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH 27 CONCLUSION 33 REFERENCES 34 APPENDIX 36 LIST OF TABLES TABLE 1, Geonetry of Locations Studied 17 TABLE 2, Rates of Change of Slope Versus Curve Ratings 31 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1. Definition of Sight Distance and Display Angle 8 FIGURE 2. Perspective Coordinate Transformation 9 FIGURE 3. Spiral Curve Calculation Equations 12 FIGURE 4. Flow Chart 14 FIGURE 5, Photograph and Perspective of Selected Location 15 FIGURE 6. Effect of Spiral Curves at Small Display Angles 19 A, No Spiral (Circular Curve) B, Completely Spiralized FIGURE 7. Effects of Spiral Curves (DA = .015 Radians, SD = 1000 Feet, D = l** and A = 10*) 20 Plate 1 A. No Spiral (Circular Curve) B, Spiral Length = 250 Feet FIGURE 8. Effects of Spiral Curves (DA = ,015 Radians, SD = 1000 Feet, D = 1° and A = 10°) 21 Plate 2 A. Spiral Length = 500 Feet B. Spiral Length = 1000 Feet (Conpletely Spiralized) FIGURE 9. Effects of Display Angle (D = 2°, A = 10°, Ig = 500 feet, = SD 500 feet) 23 Plate 1 A. Display Angle = .007 Radian B. Display Angle = .027 Radiaji FIGURE 10. -

Construction Surveying Curves

Construction Surveying Curves Three(3) Continuing Education Hours Course #LS1003 Approved Continuing Education for Licensed Professional Engineers EZ-pdh.com Ezekiel Enterprises, LLC 301 Mission Dr. Unit 571 New Smyrna Beach, FL 32170 800-433-1487 [email protected] Construction Surveying Curves Ezekiel Enterprises, LLC Course Description: The Construction Surveying Curves course satisfies three (3) hours of professional development. The course is designed as a distance learning course focused on the process required for a surveyor to establish curves. Objectives: The primary objective of this course is enable the student to understand practical methods to locate points along curves using variety of methods. Grading: Students must achieve a minimum score of 70% on the online quiz to pass this course. The quiz may be taken as many times as necessary to successful pass and complete the course. Ezekiel Enterprises, LLC Section I. Simple Horizontal Curves CURVE POINTS Simple The simple curve is an arc of a circle. It is the most By studying this course the surveyor learns to locate commonly used. The radius of the circle determines points using angles and distances. In construction the “sharpness” or “flatness” of the curve. The larger surveying, the surveyor must often establish the line of the radius, the “flatter” the curve. a curve for road layout or some other construction. The surveyor can establish curves of short radius, Compound usually less than one tape length, by holding one end Surveyors often have to use a compound curve because of the tape at the center of the circle and swinging the of the terrain. -

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This Course Is an Introduction to the Geometry of Smooth Curves and Surf

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This course is an introduction to the geometry of smooth if the velocity never vanishes). Then the speed is a (smooth) curves and surfaces in Euclidean space Rn (in particular for positive function of t. (The cusped curve β above is not regular n = 2; 3). The local shape of a curve or surface is described at t = 0; the other examples given are regular.) in terms of its curvatures. Many of the big theorems in the DE The lengthR [ : Länge] of a smooth curve α is defined as subject – such as the Gauss–Bonnet theorem, a highlight at the j j len(α) = I α˙(t) dt. (For a closed curve, of course, we should end of the semester – deal with integrals of curvature. Some integrate from 0 to T instead of over the whole real line.) For of these integrals are topological constants, unchanged under any subinterval [a; b] ⊂ I, we see that deformation of the original curve or surface. Z b Z b We will usually describe particular curves and surfaces jα˙(t)j dt ≥ α˙(t) dt = α(b) − α(a) : locally via parametrizations, rather than, say, as level sets. a a Whereas in algebraic geometry, the unit circle is typically be described as the level set x2 + y2 = 1, we might instead This simply means that the length of any curve is at least the parametrize it as (cos t; sin t). straight-line distance between its endpoints. Of course, by Euclidean space [DE: euklidischer Raum] The length of an arbitrary curve can be defined (following n we mean the vector space R 3 x = (x1;:::; xn), equipped Jordan) as its total variation: with with the standard inner product or scalar product [DE: P Xn Skalarproduktp ] ha; bi = a · b := aibi and its associated norm len(α):= TV(α):= sup α(ti) − α(ti−1) : jaj := ha; ai. -

The Ordered Distribution of Natural Numbers on the Square Root Spiral

The Ordered Distribution of Natural Numbers on the Square Root Spiral - Harry K. Hahn - Ludwig-Erhard-Str. 10 D-76275 Et Germanytlingen, Germany ------------------------------ mathematical analysis by - Kay Schoenberger - Humboldt-University Berlin ----------------------------- 20. June 2007 Abstract : Natural numbers divisible by the same prime factor lie on defined spiral graphs which are running through the “Square Root Spiral“ ( also named as “Spiral of Theodorus” or “Wurzel Spirale“ or “Einstein Spiral” ). Prime Numbers also clearly accumulate on such spiral graphs. And the square numbers 4, 9, 16, 25, 36 … form a highly three-symmetrical system of three spiral graphs, which divide the square-root-spiral into three equal areas. A mathematical analysis shows that these spiral graphs are defined by quadratic polynomials. The Square Root Spiral is a geometrical structure which is based on the three basic constants: 1, sqrt2 and π (pi) , and the continuous application of the Pythagorean Theorem of the right angled triangle. Fibonacci number sequences also play a part in the structure of the Square Root Spiral. Fibonacci Numbers divide the Square Root Spiral into areas and angle sectors with constant proportions. These proportions are linked to the “golden mean” ( golden section ), which behaves as a self-avoiding-walk- constant in the lattice-like structure of the square root spiral. Contents of the general section Page 1 Introduction to the Square Root Spiral 2 2 Mathematical description of the Square Root Spiral 4 3 The distribution -

Geodetic Position Computations

GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E. J. KRAKIWSKY D. B. THOMSON February 1974 TECHNICALLECTURE NOTES REPORT NO.NO. 21739 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of lecture notes more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E.J. Krakiwsky D.B. Thomson Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University of New Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton. N .B. Canada E3B5A3 February 197 4 Latest Reprinting December 1995 PREFACE The purpose of these notes is to give the theory and use of some methods of computing the geodetic positions of points on a reference ellipsoid and on the terrain. Justification for the first three sections o{ these lecture notes, which are concerned with the classical problem of "cCDputation of geodetic positions on the surface of an ellipsoid" is not easy to come by. It can onl.y be stated that the attempt has been to produce a self contained package , cont8.i.ning the complete development of same representative methods that exist in the literature. The last section is an introduction to three dimensional computation methods , and is offered as an alternative to the classical approach. Several problems, and their respective solutions, are presented. The approach t~en herein is to perform complete derivations, thus stqing awrq f'rcm the practice of giving a list of for11111lae to use in the solution of' a problem. -

CURVATURE E. L. Lady the Curvature of a Curve Is, Roughly Speaking, the Rate at Which That Curve Is Turning. Since the Tangent L

1 CURVATURE E. L. Lady The curvature of a curve is, roughly speaking, the rate at which that curve is turning. Since the tangent line or the velocity vector shows the direction of the curve, this means that the curvature is, roughly, the rate at which the tangent line or velocity vector is turning. There are two refinements needed for this definition. First, the rate at which the tangent line of a curve is turning will depend on how fast one is moving along the curve. But curvature should be a geometric property of the curve and not be changed by the way one moves along it. Thus we define curvature to be the absolute value of the rate at which the tangent line is turning when one moves along the curve at a speed of one unit per second. At first, remembering the determination in Calculus I of whether a curve is curving upwards or downwards (“concave up or concave down”) it may seem that curvature should be a signed quantity. However a little thought shows that this would be undesirable. If one looks at a circle, for instance, the top is concave down and the bottom is concave up, but clearly one wants the curvature of a circle to be positive all the way round. Negative curvature simply doesn’t make sense for curves. The second problem with defining curvature to be the rate at which the tangent line is turning is that one has to figure out what this means. The Curvature of a Graph in the Plane. -

Chapter 13 Curvature in Riemannian Manifolds

Chapter 13 Curvature in Riemannian Manifolds 13.1 The Curvature Tensor If (M, , )isaRiemannianmanifoldand is a connection on M (that is, a connection on TM−), we− saw in Section 11.2 (Proposition 11.8)∇ that the curvature induced by is given by ∇ R(X, Y )= , ∇X ◦∇Y −∇Y ◦∇X −∇[X,Y ] for all X, Y X(M), with R(X, Y ) Γ( om(TM,TM)) = Hom (Γ(TM), Γ(TM)). ∈ ∈ H ∼ C∞(M) Since sections of the tangent bundle are vector fields (Γ(TM)=X(M)), R defines a map R: X(M) X(M) X(M) X(M), × × −→ and, as we observed just after stating Proposition 11.8, R(X, Y )Z is C∞(M)-linear in X, Y, Z and skew-symmetric in X and Y .ItfollowsthatR defines a (1, 3)-tensor, also denoted R, with R : T M T M T M T M. p p × p × p −→ p Experience shows that it is useful to consider the (0, 4)-tensor, also denoted R,givenby R (x, y, z, w)= R (x, y)z,w p p p as well as the expression R(x, y, y, x), which, for an orthonormal pair, of vectors (x, y), is known as the sectional curvature, K(x, y). This last expression brings up a dilemma regarding the choice for the sign of R. With our present choice, the sectional curvature, K(x, y), is given by K(x, y)=R(x, y, y, x)but many authors define K as K(x, y)=R(x, y, x, y). Since R(x, y)isskew-symmetricinx, y, the latter choice corresponds to using R(x, y)insteadofR(x, y), that is, to define R(X, Y ) by − R(X, Y )= + . -

Design Data 21

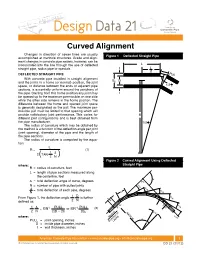

Design Data 21 Curved Alignment Changes in direction of sewer lines are usually Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe accomplished at manhole structures. Grade and align- Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe ment changes in concrete pipe sewers, however, can be incorporated into the line through the use of deflected L straight pipe, radius pipe or specials. t L 2 DEFLECTED STRAIGHT PIPE Pull With concrete pipe installed in straight alignment Bc D and the joints in a home (or normal) position, the joint ∆ space, or distance between the ends of adjacent pipe 1/2 N sections, is essentially uniform around the periphery of the pipe. Starting from this home position any joint may t be opened up to the maximum permissible on one side while the other side remains in the home position. The difference between the home and opened joint space is generally designated as the pull. The maximum per- missible pull must be limited to that opening which will provide satisfactory joint performance. This varies for R different joint configurations and is best obtained from the pipe manufacturer. ∆ 1/2 N The radius of curvature which may be obtained by this method is a function of the deflection angle per joint (joint opening), diameter of the pipe and the length of the pipe sections. The radius of curvature is computed by the equa- tion: L R = (1) 1 ∆ 2 TAN ( 2 N ) Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected where: Straight Pipe R = radius of curvature, feet Straight Pipe L = length of pipe sections measured along the centerline, feet ∆ ∆ = total deflection angle of curve, degrees P.I. -

Archimedean Spirals ∗

Archimedean Spirals ∗ An Archimedean Spiral is a curve defined by a polar equation of the form r = θa, with special names being given for certain values of a. For example if a = 1, so r = θ, then it is called Archimedes’ Spiral. Archimede’s Spiral For a = −1, so r = 1/θ, we get the reciprocal (or hyperbolic) spiral. Reciprocal Spiral ∗This file is from the 3D-XploreMath project. You can find it on the web by searching the name. 1 √ The case a = 1/2, so r = θ, is called the Fermat (or hyperbolic) spiral. Fermat’s Spiral √ While a = −1/2, or r = 1/ θ, it is called the Lituus. Lituus In 3D-XplorMath, you can change the parameter a by going to the menu Settings → Set Parameters, and change the value of aa. You can see an animation of Archimedean spirals where the exponent a varies gradually, from the menu Animate → Morph. 2 The reason that the parabolic spiral and the hyperbolic spiral are so named is that their equations in polar coordinates, rθ = 1 and r2 = θ, respectively resembles the equations for a hyperbola (xy = 1) and parabola (x2 = y) in rectangular coordinates. The hyperbolic spiral is also called reciprocal spiral because it is the inverse curve of Archimedes’ spiral, with inversion center at the origin. The inversion curve of any Archimedean spirals with respect to a circle as center is another Archimedean spiral, scaled by the square of the radius of the circle. This is easily seen as follows. If a point P in the plane has polar coordinates (r, θ), then under inversion in the circle of radius b centered at the origin, it gets mapped to the point P 0 with polar coordinates (b2/r, θ), so that points having polar coordinates (ta, θ) are mapped to points having polar coordinates (b2t−a, θ). -

The Logarithmic Spiral * the Parametric Equations for The

The Logarithmic Spiral * The parametric equations for the Logarithmic Spiral are: x(t) =aa exp(bb t) cos(t) · · · y(t) =aa exp(bb t) sin(t). · · · This spiral is connected with the complex exponential as follows: x(t) + i y(t) = aa exp((bb + i)t). The animation that is automatically displayed when you select Logarithmic Spiral from the Plane Curves menu shows the osculating circles of the spiral. Their midpoints draw another curve, the evolute of this spiral. These os- culating circles illustrate an interesting theorem, namely if the curvature is a monotone function along a segment of a plane curve, then the osculating circles are nested - because the distance of the midpoints of two osculating circles is (by definition) the length of a secant of the evolute while the difference of their radii is the arc length of the evolute between the two midpoints. (See page 31 of J.J. Stoker’s “Differential Geometry”, Wiley-Interscience, 1969). For the logarithmic spiral this implies that through every point of the plane minus the origin passes exactly one os- culating circle. Etienne´ Ghys pointed out that this leads * This file is from the 3D-XplorMath project. Please see: http://3D-XplorMath.org/ 1 to a surprise: The unit tangent vectors of the osculating circles define a vector field X on R2 0 – but this vec- tor field has more integral curves, i.e.\ {solution} curves of the ODE c0(t) = X(c(t)), than just the osculating circles, namely also the logarithmic spiral. How is this compatible with the uniqueness results of ODE solutions? Read words backwards for explanation: eht dleifrotcev si ton ztihcspiL gnola eht evruc. -

Curvature of Riemannian Manifolds

Curvature of Riemannian Manifolds Seminar Riemannian Geometry Summer Term 2015 Prof. Dr. Anna Wienhard and Dr. Gye-Seon Lee Soeren Nolting July 16, 2015 1 Motivation Figure 1: A vector parallel transported along a closed curve on a curved manifold.[1] The aim of this talk is to define the curvature of Riemannian Manifolds and meeting some important simplifications as the sectional, Ricci and scalar curvature. We have already noticed, that a vector transported parallel along a closed curve on a Riemannian Manifold M may change its orientation. Thus, we can determine whether a Riemannian Manifold is curved or not by transporting a vector around a loop and measuring the difference of the orientation at start and the endo of the transport. As an example take Figure 1, which depicts a parallel transport of a vector on a two-sphere. Note that in a non-curved space the orientation of the vector would be preserved along the transport. 1 2 Curvature In the following we will use the Einstein sum convention and make use of the notation: X(M) space of smooth vector fields on M D(M) space of smooth functions on M 2.1 Defining Curvature and finding important properties This rather geometrical approach motivates the following definition: Definition 2.1 (Curvature). The curvature of a Riemannian Manifold is a correspondence that to each pair of vector fields X; Y 2 X (M) associates the map R(X; Y ): X(M) ! X(M) defined by R(X; Y )Z = rX rY Z − rY rX Z + r[X;Y ]Z (1) r is the Riemannian connection of M. -

Lecture 8: the Sectional and Ricci Curvatures

LECTURE 8: THE SECTIONAL AND RICCI CURVATURES 1. The Sectional Curvature We start with some simple linear algebra. As usual we denote by ⊗2(^2V ∗) the set of 4-tensors that is anti-symmetric with respect to the first two entries and with respect to the last two entries. Lemma 1.1. Suppose T 2 ⊗2(^2V ∗), X; Y 2 V . Let X0 = aX +bY; Y 0 = cX +dY , then T (X0;Y 0;X0;Y 0) = (ad − bc)2T (X; Y; X; Y ): Proof. This follows from a very simple computation: T (X0;Y 0;X0;Y 0) = T (aX + bY; cX + dY; aX + bY; cX + dY ) = (ad − bc)T (X; Y; aX + bY; cX + dY ) = (ad − bc)2T (X; Y; X; Y ): 1 Now suppose (M; g) is a Riemannian manifold. Recall that 2 g ^ g is a curvature- like tensor, such that 1 g ^ g(X ;Y ;X ;Y ) = hX ;X ihY ;Y i − hX ;Y i2: 2 p p p p p p p p p p 1 Applying the previous lemma to Rm and 2 g ^ g, we immediately get Proposition 1.2. The quantity Rm(Xp;Yp;Xp;Yp) K(Xp;Yp) := 2 hXp;XpihYp;Ypi − hXp;Ypi depends only on the two dimensional plane Πp = span(Xp;Yp) ⊂ TpM, i.e. it is independent of the choices of basis fXp;Ypg of Πp. Definition 1.3. We will call K(Πp) = K(Xp;Yp) the sectional curvature of (M; g) at p with respect to the plane Πp. Remark. The sectional curvature K is NOT a function on M (for dim M > 2), but a function on the Grassmann bundle Gm;2(M) of M.