The Great Famine: a Local History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newry & Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan

Newry & Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan Ulster Wildlife Trust watch Contents Foreword .................................................................................................1 Biodiversity in the Newry and Mourne District ..........................2 Newry and Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan ..4 Our local priority habitats and species ..........................................5 Woodland ..............................................................................................6 Wetlands ..................................................................................................8 Peatlands ...............................................................................................10 Coastal ....................................................................................................12 Marine ....................................................................................................14 Grassland ...............................................................................................16 Gardens and urban greenspace .....................................................18 Local action for Newry and Mourne’s species .........................20 What you can do for Newry and Mourne’s biodiversity ......22 Glossary .................................................................................................24 Acknowledgements ............................................................................24 Published March 2009 Front Cover Images: Mill Bay © Conor McGuinness, -

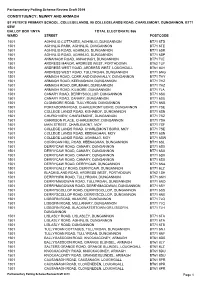

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

The Belfast Gazette, May 30, 1930. 683 1

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, MAY 30, 1930. 683 PROVISIONAL LIST No. 1689. LAND PURCHASE COMMISSION, NORTHERN IRELAND. NORTHERN IRELAND LAND ACT, 1925. ESTATE OF GEORGE SCOTT. County of Armagh. Record No. N.I. 1454. WHEREAS the above-mentioned George Scott claims to be the Owner of land in the Townlands of Annaclaie and Killuney, in the Barony of Oneilland West, and in the Townlands of Corporation, Drumadd, Ballynahone More, Knockaconey, and Tullygoonigan, Barony of Armagh, all in the County of Armagh. Now in pursuance of the provisions of Section 17, Sub-section 2, of the above Act the Land Purchase Commission Northern Ireland, hereby publish the following Provisional last of all land in the said Townlands of which the said George Scott claims to be the Owner, which will become vested in the said Commission by virtue of Part II of the Northern Ireland Land Act, 1925, on the Appointed Day to be hereafter fixed. Standard Standard No on Purchase Price Map filed Annuity if land Reg. Name of Tenant. Postal Address. Barony. Townland. In Land Area. Bent. if land becomes Purchase becomes vested No. Oommls- vested A. B. P. £ s. d.£ s. d. £ B. d Holdings subject to Judicial Bents fixed before the 16th August, 1896. 1 Anne McLaughlin : Tullygooni- Armagh Tullygooni- 3 5 1 20 4 10 03 3 2 66 9 10 (spinster) gan, gan Allistragh, Co. Armagh. 3 Do. do. do. do. 11, 11A 317 3 0 02 2 2 44 7.9 11B 11C 4 : Joseph McCrealy do. do. do. 12 2 0 20 1 15 01 4 6 25 15 9 5 John McArdle Knockaconey, do. -

The Poets Trails and Other Walks a Selection of Routes Through Exceptional Countryside Rich in Folklore, Archaeology, Geology and Wildlife

The Poets Trails and other walks A selection of routes through exceptional countryside rich in folklore, archaeology, geology and wildlife www.ringofgullion.org BELLEEK CAMLOUGH NEWRY Standing A25 Stone Welcome to walks in Derrylechagh Lough the Ring of Gullion Camlough Courtney Cashel Mountain The Ring of Gullion lies within a Mountain Cam Lough region long associated with an Chambered ancient frontier that began with Grave Slieveacarnane Militown Lough the earliest records of man’s Greenon The Long Stone Lough habitation in Ireland. It was along these roads and fields, and over Slievenacappel these hills and mountains, that 4 Killevy 3 1 St Bline’s Church 3 Cúchulainn and the Red Branch B 1 Well 1 B Knights, the O’Neills and 0 3 B O’Hanlons roamed, battled and Slieve Gullion MEIGH died. The area, which has always 1 A Victoria Lock represented a frontier from the A Adventure ancient Iron Age defences of the 2 9 MULLAGHBANE Playground WARRENPOINT Dorsey, through the Anglo- Norman Pale, and latterly the SILVERBRIDGE modern border, is alive with history, scenic beauty and culture. DRUMINTEE JONESBOROUGH Slieve This area reflects the mix of Breac cultures from Neolithic to the FORKHILL CREGGAN Black present, while the rolling Kilnasaggart Mountain Inscribed countryside lends itself to the Stone enjoyment of peaceful walks, excellent fishing and a friendly welcome at every stop. Key to Map Creggan Route Forkhill Route Ballykeel Route Slieve Gullion Route Camlough Route Annahaia Route Glassdrumman Lake Art Mac Cumhaigh’s Headstone Ring of Gullion Way Marked Way 02 | www.ringofguillion.org www.ringofguillion.org | 03 POETS TRAIL – CREGGAN ROUTE POETS TRAIL – CREGGAN ROUTE Did You Know? Creggan graveyard is a truly ecumenical place as members of both Catholic and Protestant denominations still bury in its fragrant clay. -

Copy of Nipx List 16 Nov 07

Andersonstown 57 Glen Road Belfast BT11 8BB Antrim 27-28 Castle Centre Antrim CO ANTRIM BT41 4AR Ards Centre Ards Shopping Centre Circular Road Newtownards County Down N Ireland BT23 4EU Armagh 31 Upper English St. Armagh BT61 7BA BALLEYHOLME SPSO 99 Groomsport Road Bangor County Down BT20 5NG Ballyhackamore 342 Upper Newtonards Road Belfast BT4 3EX Ballymena 51-63 Wellington Street Ballymena County Antrim BT43 6JP Ballymoney 11 Linenhall Street Ballymoney County Antrim BT53 6RQ Banbridge 26 Newry Street Banbridge BT32 3HB Bangor 143 Main Street Bangor County Down BT20 4AQ Bedford Street Bedford House 16-22 Bedford Street Belfast BT2 7FD Belfast 25 Castle Place Belfast Northern Ireland BT1 1BB BLACKSTAFF SPSO Unit 1- The Blackstaff Stop 520 Springfield Road Belfast County Antrim BT12 7AE Brackenvale Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 8EU Brownstown Road 11 Brownstown Road Portadown Craigavon BT62 4EB Carrickfergus CO-OP Superstore Belfast Road Carrickfergus County Antrim BT38 8PH CHERRYVALLEY 15 Kings Square Belfast BT5 7EA Coalisland 28A Dungannon Road Coalisland Dungannon BT71 4HP Coleraine 16-18 New Row Coleraine County Derry BT52 1RX Cookstown 49 James Street Cookstown County Tyrone BT80 8XH Downpatrick 65 Lower Market Street Downpatrick County Down BT30 6LZ DROMORE 37 Main Street Dromore Co. Tyrone BT78 3AE Drumhoe 73 Glenshane Raod Derry BT47 3SF Duncairn St 238-240 Antrim road Belfast BT15 2AR DUNGANNON 11 Market Square Dungannon BT70 1AB Dungiven 144 Main Street Dungiven Derry BT47 4LG DUNMURRY 148 Kingsway Dunmurray Belfast N IRELAND -

Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the Historiography of the Great Famine Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel Et L’Historiographie De La Grande Famine

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XIX-2 | 2014 La grande famine en irlande, 1845-1851 Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel et l’historiographie de la Grande Famine Christophe Gillissen Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/281 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.281 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2014 Number of pages: 195-212 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Christophe Gillissen, “Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XIX-2 | 2014, Online since 01 May 2015, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/281 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ rfcb.281 Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine Christophe GILLISSEN Université de Caen – Basse Normandie The Great Irish Famine produced a staggering amount of paperwork: innumerable letters, reports, articles, tables of statistics and books were written to cover the catastrophe. Yet two distinct voices emerge from the hubbub: those of Charles Trevelyan, a British civil servant who supervised relief operations during the Famine, and John Mitchel, an Irish nationalist who blamed London for the many Famine-related deaths.1 They may be considered as representative to some extent, albeit in an extreme form, of two dominant trends within its historiography as far as London’s role during the Famine is concerned. -

County Report

FOP vl)Ufi , NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE PRICE 85p NET NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE CONTENTS PART 1— EXPLANATORY NOTES AND DEFINITIONS Page Area (hectares) vi Population vi Dwellings vi Private households vii Rooms vii Tenure vii Household amenities viii Cars and garaging ....... viii Non-private establishments ix Usual address ix Age ix Birthplace ix Religion x Economic activity x Presentation conventions xi Administrative divisions xi PART II--TABLES Table Areas for which statistics Page No. Subject of Table are stated 1. Area, Buildings for Habitation and County 1 Population, 1971 2. Population, 1821-1971 ! County 1 3. Population 1966 and 1971, and Intercensal Administrative Areas 1 Changes 4. Acreage, Population, Buildings for Administrative Areas, Habitation and Households District Electoral Divisions 2 and Towns 5. Ages by Single Years, Sex and Marital County 7 Condition 6. Population under 25 years by Individual Administrative Areas 9 Years and 25 years and over by Quinquennial Groups, Sex and Marital Condition 7. Population by Sex, Marital Condition, Area Administrative Areas 18 of Enumeration, Birthplace and whether visitor to Northern Ireland 8. Religions Administrative Areas 22 9. Private dwellings by Type, Households, | Administrative Areas 23 Rooms and Population 10. Dwellings by Tenure and Rooms Administrative Areas 26 11. Private Households by Size, Rooms, Administrative Areas 30 Dwelling type and Population 12. -

Iveagh Sports Grounds Sold

EE FR l Conveyancing l Wills and Probate l Personal Injuries l Employment Law LOCAL Competitive conveyancing prices SOUTH EDITION for buying and selling a home! Christmas 2017 15B St. Agnes Road, Crumlin, Dublin 12 Phone: 087 252 4064 • Email: [email protected] • www.localnews.ie Phone: 01 531 3300 • www.ardaghlaw.ie Crumlin l Drimnagh l Kimmage l Walkinstown l Terenure l Rathfarnnham l Rialto l Baellyfermot l Ratwhmines l Harolds Cross ls Kilnamanagh l Templeogue l Inchicore l Inner City l Tallaght l Rathgar l Ranelagh IVEAGH SPORTS l Extensions, Renovations l All GRAnt woRk cARRiEd out. l Registered & fully insured l insurance claim work GROUNDS SOLD l Architects Plans For some years now ru - mours have been circulat - Ring (01) 465 2412 ing about the future of the Mobile: 086 311 2869 Iveagh Grounds on Crumlin Road. While not much of this sports ground fronts Email: [email protected] the main road the site is substantial and is thought www.farrellbuilding.ie to be over 17 acres. What developer would not like to get their hands on this prime site. This fine sports facility was home to League of Ireland club St James’ Gate and indeed up to a couple of years ago the rem - nants of a seated stand were still there in its run down NEW MENU state a memory of a former CLUB SANDWICHES, glorious time for the SALAD PLATES SOUPS club.Up to last season it was still b being used by the Le - BOOK YOUR PARTY/CELEBRATION inster Football League for fi - nals in many of its division PHONE; (01) 455 7861 finals. -

Downloaded the Audio Tours

The Ring of Gullion Landscape Conservation Action Plan Newry and Mourne District Council 2/28/2014 Contents The Ring of Gullion Landscape Partnership Board is grateful financial support for this scheme. 2 Contents Contents Executive summary 6 Introduction 9 Plan author 9 Landscape Conservation Action Plan – Scheme Overview 13 Section 1 – Understanding the Ring of Gullion 19 Introduction 19 The Project Boundary 19 Towns and Villages 20 The Landscape Character 30 The Ring of Gullion Landscape 31 Landscape Condition and Sensitivity to Change 32 Ring of Gullion Geodiversity Profile 33 Ring of Gullion Biodiversity Profile 38 The Heritage of the Ring of Gullion 47 Management Information 51 Section 2 – Statement of Significance 53 Introduction 53 Natural Heritage 54 Archaeological and Built Heritage 59 Geological Significance 62 Historical Significance 63 Industrial Heritage 67 Twentieth Century Military Significance 68 3 Contents Cultural and Human Heritage 68 Importance to Local Communities 73 Section 3 – Risks and Opportunities 81 Introduction 81 Urban proximity and development 81 Crime and anti-social behaviour 82 Wildlife 83 Pressures on farming and loss of traditional farming skills 84 Recreational pressure 85 Illegal recreational activity 87 Lack of knowledge and understanding 87 Climate change 88 Audience barriers 89 National/international economic downturn 90 A forgotten heritage and the loss of traditional skills 90 LPS implementation and sustainability 92 Consultations 93 Conclusions from risks and opportunities 93 Section 4 – Aims -

Revised-Fixture-Booklet2020.Pdf

Armagh County Board, Athletic Grounds, Dalton Road, Armagh, BT60 4AE. Fón: 02837 527278. Office Hrs: Mon-Fri 9AM – 5PM. Closed Daily 1PM – 2PM. CONTENTS Oifigigh An Choiste Contae 1-5 Armagh GAA Staff 6-7 GAA & Provincial Offices 8 Media 9 County Sub Committees 10-11 Club Contacts 12-35 2020 Adult Referees 36-37 County Bye-Laws 38-46 2020 Amended Football & League Reg 47-59 Championship Regulations 60-69 County Fixtures Oct 2020 – Dec 2020 70-71 Club Fixtures 72-94 OIFIGIGH AN CHOISTE CONTAE CATHAOIRLEACH Mícheál Ó Sabhaois (Michael Savage) Fón: 07808768722 Email: [email protected] LEAS CATHAOIRLEACH Séamus Mac Aoidh (Jimmy McKee) Fón: 07754603867 Email: [email protected] RÚNAÍ Seán Mac Giolla Fhiondain (Sean McAlinden) Fón: 07760440872 Email: [email protected] LEAS RÚNAÍ Léana Uí Mháirtín (Elena Martin) Fón: 07880496123 Email: [email protected] CISTEOIR Gearard Mac Daibhéid (Gerard Davidson) Fón: 07768274521 Email: [email protected] Page | 1 CISTEOIR CÚNTA Tomas O hAdhmaill (Thomas Hamill) Fón: 07521366446 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH FORBARTHA Liam Rosach (Liam Ross) Fón: 07720321799 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH CULTÚIR Barra Ó Muirí Fón: 07547306922 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH CAIDRIMH PHOIBLÍ Clár Ní Siail (Claire Shields) Fón: 07719791629 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH IOMANA Daithi O’Briain (David O Brien) Fón: 07775176614 Email: [email protected] TEACHTA CHOMHAIRLE ULADH 1 Pádraig Ó hEachaidh (Padraig -

(HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children's Social Work

Northern Ireland Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children’s Social Work Belfast HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 028 90507000 Areas Greater Belfast area Further Contact Details Greater Belfast Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) 110 Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 6HD Website http://www.belfasttrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) South Eastern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001000300 Areas Lisburn, Dunmurry, Moira, Hillsborough, Bangor, Newtownards, Ards Peninsula, Comber, Downpatrick, Newcastle and Ballynahinch Further Contact Details Greater Lisburn Gateway North Down Gateway Team Down Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Team James Street Children’s Services Stewartstown Road Health Newtownards, BT23 4EP 81 Market Street Centre Tel: 028 91818518 Downpatrick, BT30 6LZ 212 Stewartstown Road Fax: 028 90564830 Tel: 028 44613511 Dunmurry Fax: 028 44615734 Belfast, BT17 0FG Tel: 028 90602705 Fax: 028 90629827 Website http://www.setrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) Northern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001234333 Areas Antrim, Carrickfergus, Newtownabbey, Larne, Ballymena, Cookstown, Magherafelt, Ballycastle, Ballymoney, Portrush and Coleraine Further Contact Details Central Gateway Team South Eastern Gateway Team Northern Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Unit 5A, Toome Business The Beeches Coleraine -

Who Made My Breakfast? Who Made My Breakfast?

hastingshotels.com Who made my breakfast? Who made my breakfast? Breakfast is commonly regarded to be the most important meal of the day and at Hastings Hotels we agree! That is why we have gone the extra mile to find the finest locally sourced fresh produce to give you a real Irish breakfast experience. Our traditional breakfast menu showcases the very best of Northern Ireland’s seasonal larder and heritage from a carefully selected group of local and artisanal suppliers. This produce stands out in terms of its quality and flavour and enables our chefs to prepare the most delicious start to your day! We are delighted to be able to share our suppliers’ stories with you, so you can see for yourself the care, quality and local expertise that all go into making sure your breakfast is a true taste of Ulster. Please feel free to take this booklet with you as a keepsake of your visit to Hastings Hotels. Whatever your day ahead holds, we hope you enjoy your breakfast with us! Apple Juice P. McCann & Sons were founded in 1968 in a small pack house at the back of the McCann family homestead outside Loughgall, County Armagh. With over 40 years’ experience, the company is now into its third generation of the McCann family. McCanns are the leading packers and processors of apples, pears, pure apple juice and cider in the area. McCanns are supplied by a number of growers from all over Ireland and the UK, supplying dessert apples, Bramley apples and pears and they are well known throughout Ireland and the UK for the service and products they provide.