MANUSCRIPT PRODUCTION ASSOCIATED with HAMSEN* As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff This study appears as part III of Toumanoff's Studies in Christian Caucasian History (Georgetown, 1963), pp. 277-354. An earlier version appeared in the journal Le Muséon 72(1959), pp. 1-36 and 73(1960), pp. 73-106. The Orontids of Armenia Bibliography, pp. 501-523 Maps appear as an attachment to the present document. This material is presented solely for non-commercial educational/research purposes. I 1. The genesis of the Armenian nation has been examined in an earlier Study.1 Its nucleus, succeeding to the role of the Yannic nucleus ot Urartu, was the 'proto-Armenian,T Hayasa-Phrygian, people-state,2 which at first oc- cupied only a small section of the former Urartian, or subsequent Armenian, territory. And it was, precisely, of the expansion of this people-state over that territory, and of its blending with the remaining Urartians and other proto- Caucasians that the Armenian nation was born. That expansion proceeded from the earliest proto-Armenian settlement in the basin of the Arsanias (East- ern Euphrates) up the Euphrates, to the valley of the upper Tigris, and espe- cially to that of the Araxes, which is the central Armenian plain.3 This expand- ing proto-Armenian nucleus formed a separate satrapy in the Iranian empire, while the rest of the inhabitants of the Armenian Plateau, both the remaining Urartians and other proto-Caucasians, were included in several other satrapies.* Between Herodotus's day and the year 401, when the Ten Thousand passed through it, the land of the proto-Armenians had become so enlarged as to form, in addition to the Satrapy of Armenia, also the trans-Euphratensian vice-Sa- trapy of West Armenia.5 This division subsisted in the Hellenistic phase, as that between Greater Armenia and Lesser Armenia. -

Social Change in Eleventh-Century Armenia: the Evidence from Tarōn Tim Greenwood (University of St Andrews)

Social Change in Eleventh-Century Armenia: the evidence from Tarōn Tim Greenwood (University of St Andrews) The social history of tenth and eleventh-century Armenia has attracted little in the way of sustained research or scholarly analysis. Quite why this should be so is impossible to answer with any degree of confidence, for as shall be demonstrated below, it is not for want of contemporary sources. It may perhaps be linked to the formative phase of modern Armenian historical scholarship, in the second half of the nineteenth century, and its dominant mode of romantic nationalism. The accounts of political capitulation by Armenian kings and princes and consequent annexation of their territories by a resurgent Byzantium sat very uncomfortably with the prevailing political aspirations of the time which were validated through an imagined Armenian past centred on an independent Armenian polity and a united Armenian Church under the leadership of the Catholicos. Finding members of the Armenian elite voluntarily giving up their ancestral domains in exchange for status and territories in Byzantium did not advance the campaign for Armenian self-determination. It is also possible that the descriptions of widespread devastation suffered across many districts and regions of central and western Armenia at the hands of Seljuk forces in the eleventh century became simply too raw, too close to the lived experience and collective trauma of Armenians in these same districts at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, to warrant -

Hayek's the Constitution of Liberty

Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty An Account of Its Argument EUGENE F. MILLER The Institute of Economic Affairs contenTs The author 11 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Foreword by Steven D. Ealy 12 The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Summary 17 Westminster Editorial note 22 London sw1p 3lb Author’s preface 23 in association with Profile Books Ltd The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public 1 Hayek’s Introduction 29 understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, by analysing Civilisation 31 and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Political philosophy 32 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2010 The ideal 34 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a PART I: THE VALUE OF FREEDOM 37 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. 2 Individual freedom, coercion and progress A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. (Chapters 1–5 and 9) 39 isbn 978 0 255 36637 3 Individual freedom and responsibility 39 The individual and society 42 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Limiting state coercion 44 Director General at the address above. -

Armenia, Republic of | Grove

Grove Art Online Armenia, Republic of [Hayasdan; Hayq; anc. Pers. Armina] Lucy Der Manuelian, Armen Zarian, Vrej Nersessian, Nonna S. Stepanyan, Murray L. Eiland and Dickran Kouymjian https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T004089 Published online: 2003 updated bibliography, 26 May 2010 Country in the southern part of the Transcaucasian region; its capital is Erevan. Present-day Armenia is bounded by Georgia to the north, Iran to the south-east, Azerbaijan to the east and Turkey to the west. From 1920 to 1991 Armenia was a Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR, but historically its land encompassed a much greater area including parts of all present-day bordering countries (see fig.). At its greatest extent it occupied the plateau covering most of what is now central and eastern Turkey (c. 300,000 sq. km) bounded on the north by the Pontic Range and on the south by the Taurus and Kurdistan mountains. During the 11th century another Armenian state was formed to the west of Historic Armenia on the Cilician plain in south-east Asia Minor, bounded by the Taurus Mountains on the west and the Amanus (Nur) Mountains on the east. Its strategic location between East and West made Historic or Greater Armenia an important country to control, and for centuries it was a battlefield in the struggle for power between surrounding empires. Periods of domination and division have alternated with centuries of independence, during which the country was divided into one or more kingdoms. Page 1 of 47 PRINTED FROM Oxford Art Online. © Oxford University Press, 2019. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

Sanat Kumara John Nash [Published in the Beacon, March 2002, Pp

Sanat Kumara John Nash [Published in The Beacon, March 2002, pp. 13-20.] Sanat Kumara, Lord of the World, Ancient of Days, Fountainhead of the Will, the Great Sacrifice, the One Initiator, Melchizedek, the King. These titles refer to the great Individuality who rules the world, presides over the Council of Shamballa, heads the Planetary Hierarchy, and wields the Rod of Initiation for the three major initiations. Sanat Kumara, in the Tibetan’s words, is “He to Whom Christ referred when He said, ‘I and My Father are One.’”1 The name “Sanat Kumara” is Sanskrit for “Eternal Youth,” or more poetically “Youth of Endless Summers,” providing two more titles. But who, precisely, is Sanat Kumara, what is His mission on Earth, and what is His relationship to the Planetary Logos? The present study attempts to shed light on the identity and role of One who is clearly of the utmost significance for the planet and all of us. So great is this significance that such a study must be approached with both reverence and caution. The Planetary Logos The seven planetary Logoi in our solar system are great Lives identified variously as the Heavenly Men, Silent Watchers, Planetary Spirits, Seven Spirits before the Throne, Elohim, or Dhyan-Chohans. All the planetary Logoi passed through the human kingdom in previous cycles and, after attaining adeptship, chose the third of seven paths of the Way of the Higher Evolution, which “leads to the higher levels of the cosmic mental plane.”2 The life of a planetary Logos is expressed through a planetary scheme consisting of seven chains, each of which in turn consists of seven globes, for a total of 49 globes. -

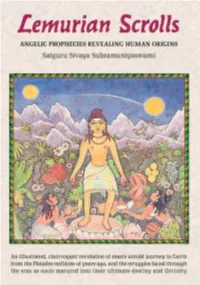

Lemurian-Scrolls.Pdf

W REVIEWS & COMMENTS W Sri Sri Swami Satchidananda, people on the planet. The time is now! Thank you Founder of Satchidananda so much for the wonderful information in your Ashram and Light of Truth book! It has also opened up many new doorways Universal Shrine (LOTUS); for me. renowned yoga master and visionary; Yogaville, Virginia K.L. Seshagiri Rao, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus, Lemurian Scrolls is a fascinating work. I am sure University of Virginia; Editor of the quarterly the readers will find many new ideas concern- journal World Faiths ing ancient mysteries revealed in this text, along Encounter; Chief Editor with a deeper understanding of their impor- of the forthcoming tance for the coming millenium. Encyclopedia of Hinduism Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, a widely recog- Patricia-Rochelle Diegel, nized spiritual preceptor of our times, un- Ph.D, well known teacher, veils in his Lemurian Scrolls esoteric wisdom intuitive healer and concerning the divine origin and goal of life consultant on past lives, for the benefit of spiritual aspirants around the human aura and numerology; Las Vegas, the globe. Having transformed the lives of Nevada many of his disciples, it can now serve as a source of moral and spiritual guidance for I have just read the Lemurian Scrolls and I am the improvement and fulfillment of the indi- amazed and pleased and totally in tune with vidual and community life on a wider scale. the material. I’ve spent thirty plus years doing past life consultation (approximately 50,000 to Ram Swarup, intellectual date). Plus I’ve taught classes, seminars and re- architect of Hindu treats. -

Armenian Traditional Black Youths: the Earliest Sources1

Armenian Traditional Black Youths: the 1 Earliest Sources Armen Petrosyan Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Yerevan, Armenia [email protected] In this article it is argued that the traditional figure of the Armenian folklore “black youth” is derived from the members of the war-band of the thunder god, mythological counterparts of the archaic war-bands of youths. The blackness of the youths is associated with igneous initiatory rituals. The best parallels of the Armenian heroes are found in Greece, India, and especially in Ossetia and other Caucasian traditions, where the Indo-European (particularly Alanian-Ossetian) influence is significant. In several medieval Armenian songs young heroes are referred to as t‘ux manuks ‘black youths,’ t‘ux ktriçs ‘black braves,’ or simply t‘uxs ‘blacks’ (see Mnatsakanyan 1976, which remains the best and comprehensive work on these figures, and Harutyunyan and Kalantaryan 2001, where several articles pertaining to this theme are published). Also, T‘ux manuk is the appellation of numerous ruined pilgrimage sanctuaries. A. Mnatsakanyan, the first investigator of these traditional figures, considered them in connection with the fratries of youths, whose remnants survived until medieval times (Mnatsakanyan 1976: 193 ff.).2 The study of the t‘ux manuks should be based on revelation of their specific characteristics and comparison with similar figures of other traditions. In this respect, the study of the T‘ux manuk sanctuaries and their legends 1This article represents an abridged and updated version of Petrosyan 2001. 2In Armenian folklore the figures of similar names – t‘uxs (‘blacks’) and alek manuks (‘good youths’) – figure as evil spirits (Alishan 1895: 205, 217). -

Epenthesis and Prosodic Structure in Armenian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Epenthesis and prosodic structure in Armenian: A diachronic account A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Indo-European Studies by Jessica L. DeLisi 2015 © Copyright by Jessica L. DeLisi 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Epenthesis and prosodic structure in Armenian: A diachronic account by Jessica L. DeLisi Doctor of Philosophy in Indo-European Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor H. Craig Melchert, Chair In this dissertation I will attempt to answer the following question: why does Classical Armenian have three dierent reexes for the Proto-Armenian epenthetic vowel word- initially before old Proto-Indo-European consonant clusters? Two of the vowels, e and a, occur in the same phonological environment, and even in doublets (e.g., Classical ełbayr beside dialectal ałbär ‘brother’). The main constraint driving this asymmetry is the promotion of the Sonority Sequenc- ing Principle in the grammar. Because sibilants are more sonorous than stops, the promo- tion of the Sonority Sequencing Principle above the Strict Layer Hypothesis causes speak- ers to create a semisyllable to house the sibilant extraprosodically. This extraprosodic structure is not required for old consonant-resonant clusters since they already conform to the Sonority Sequencing Principle. Because Armenian has sonority-sensitive stress, the secondary stress placed on word-initial epenthetic vowels triggers a vowel change in all words without extraprosodic structure, i.e. with the old consonant-resonant clusters. Therefore Proto-Armenian */@łbayR/ becomes Classical Armenian [èł.báyR] ‘brother,’ but Proto-Armenian */<@s>tipem/ with extraprosodic <@s> becomes [<@s>.tì.pém] ‘I rush’ because the schwa is outside the domain of stress assignment. -

REWRITING CAUCASIAN HISTORY the Medieval Armenian Adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles the Original Georgian Texts and the Armenian Adaptation

OXFORD ORIENTAL MONOGRAPHS REWRITING CAUCASIAN HISTORY The Medieval Armenian Adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles The Original Georgian Texts and The Armenian Adaptation Translated with Introduction and Commentary by ROBERT W. THOMSON Published with the Support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD Oxford Oriental Monographs This new series of monographs from the Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, will make available the results of recent research by scholars connected with the Faculty. Its range of subject-matter includes language, literature, thought, history and art; its geographical scope extends from the Mediterranean and Caucasus to East Asia. The emphasis will be more on special ist studies than on works of a general nature. Editorial Board John Baines Professor o f Egyptology Glen Dudbridge Shaw Professor of Chinese Alan Jones Reader in Islamic Studies Robert Thomson Calouste Gulbenkian Professor o f Armenian Studies Titles in the Series Sufism and Islamic Reform in Egypt The Battle for Islamic Tradition Julian Johansen The Early Porcelain Kilns of Japan Arita in the first half of the Seventeenth Century Oliver Impey Rewriting Caucasian History The Medieval Armenian Adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles THE ORIGINAL GEORGIAN TEXTS AND THE ARMENIAN ADAPTATION Translated with Introduction and Commentary by ROBERT W. THOMSON CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD 1996 Oxford University Press, Walton Street, Oxford 0x2 6 d p Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a trade mark o f Oxford University Press Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Robert W. -

Racial and Ethnic Evolution in Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy Peter Staudenmaier Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 2-1-2008 Race and Redemption: Racial and Ethnic Evolution in Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy Peter Staudenmaier Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Nova Religio, Vol. 11, No. 3 (February 2008): 4-36. DOI. © 2008 by University of California Press. Copying and permissions notice: Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. Copyright Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the Regents of the University of California/on the University of California Press for libraries and other users, provided that they are registered with and pay the specified fee via Rightslink® on JSTOR (http://www.jstor.org/r/ucal) or directly with the Copyright Clearance Center, http://www.copyright.com. Used with permission. NR1103_02 qxd 11/15/07 6:10 PM Page 4 Race and Redemption Racial and Ethnic Evolution in Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy Peter Staudenmaier ABSTRACT: With its origins in modern Theosophy, Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy is built around a racial view of human nature arranged in a hierarchical framework. This article examines the details of the Anthroposophical theory of cosmic and individual redemption and draws out the characteristic assumptions about racial and ethnic difference that underlie it. Particular attention is given to textual sources unavailable in English, which reveal the specific features of Steiner’s account of “race evolution” and “soul evolution.” Placing Steiner’s worldview in its historical and ideological context, the article highlights the contours of racial thinking within a prominent alternative spiritual movement and delineates the central role of a racially configured conception of evolution within Anthroposophy past and present. -

The Jeu D'adam: MS Tours 927 and the Provenance of the Play

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Early Drama, Art, and Music Medieval Institute Publications 11-30-2017 The Jeu d'Adam: MS Tours 927 and the Provenance of the Play Christophe Chaguinian Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/mip_edam Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chaguinian, Christophe, "The Jeu d'Adam: MS Tours 927 and the Provenance of the Play" (2017). Early Drama, Art, and Music. 2. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/mip_edam/2 This Edited Collection is brought to you for free and open access by the Medieval Institute Publications at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Early Drama, Art, and Music by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Jeu d’Adam EARLY DRAMA, ART, AND MUSIC Series Editors David Bevington University of Chicago Robert Clark Kansas State University Jesse Hurlbut Independent Scholar Alexandra Johnston University of Toronto Veronique B. Plesch Colby College ME Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences The Jeu d’Adam MS Tours 927 and the Provenance of the Play Edited by Christophe Chaguinian Early Drama, Art, and Music MedievaL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2017 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Chaguinian, Christophe, editor. Title: The Jeu d’Adam : MS Tours 927 and the provenance of the play / edited by Christophe Chaguinian. Description: Kalamazoo : Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, [2017] | Series: Early drama, art, and music monograph series | Includes bibliographical references.