Oblique Color Vision in an Open-Habitat Bird: Spectral Sensitivity, Photoreceptor Distribution and Behavioral Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Hummingbirds See in Ultraviolet?

The Open Medical Informatics Journal, 2009, 3, 9-12 9 Open Access Do Hummingbirds See in Ultraviolet? M. Curé*,1 and A.G. Palacios2 1Departamento de Física y Astronomía, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile 2Centro de Neurociencia de Valparaíso, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile Abstract: We present a numerical model to fit the electroretinogram (ERG), a gross evoked eye visual potential, that originate in the retina through photons absorption by photoreceptors and then involve the contribution form others retinal neurons. We use the ERG measured in a hummingbird, to evaluate the most likely retinal mechanism - cones visual pig- ments and oil-droplets - that participate in their high dimensional tetra or pentachromatic color hyperspace. The model - a nonlinear fit - appears to be a very useful tool to predict the underlying contribution visual mechanism for a variety of retinal preparation. Keywords: Color vision, electroretinogram, non lineal model. 1. INTRODUCTION high concentrations. Double cones have L visual pigments and are screened by a variety of galloxanthin and -carotene A critical question in visual sciences is to determinate the types of photoreceptors that contribute - for a particular eye - mixtures [2, 8, 10-12]. The final cone mechanism sensitivity to the overall retinal spectral sensitivity. We have developed a is then determined by combining the cone visual pigment mathematical model that helps to answer this question. As a absorption and oil-droplet transmittance. In many birds, case study, we have used the electroretinogram results of a ultraviolet (UV) is a color that is believed to be involved in diurnal bird, the Firecrown hummingbirds. -

Wild Hummingbirds Discriminate Nonspectral Colors

Wild hummingbirds discriminate nonspectral colors Mary Caswell Stoddarda,b,1, Harold N. Eysterb,c,2, Benedict G. Hogana,b,2, Dylan H. Morrisa, Edward R. Soucyd, and David W. Inouyeb,e aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; bRocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, Crested Butte, CO 81224; cInstitute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada; dCenter for Brain Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; and eDepartment of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 Edited by Scott V. Edwards, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved April 28, 2020 (received for review November 5, 2019) Many animals have the potential to discriminate nonspectral UV- or violet-sensitive (UVS/VS), short-wave–sensitive (SWS), colors. For humans, purple is the clearest example of a nonspectral medium-wave–sensitive (MWS), and long-wave–sensitive (LWS) color. It is perceived when two color cone types in the retina (blue color cones. Indirect evidence for avian tetrachromacy comes and red) with nonadjacent spectral sensitivity curves are pre- from the general agreement of behavioral data with a model that dominantly stimulated. Purple is considered nonspectral because predicts discrimination thresholds from opponent signals stem- no monochromatic light (such as from a rainbow) can evoke this ming from four single color cone types (8, 9). More directly, simultaneous stimulation. Except in primates and bees, few color-matching experiments (10) and tests designed to stimulate behavioral experiments have directly examined nonspectral color discrimination, and little is known about nonspectral color per- specific photoreceptors (11, 12) have suggested that avian color ception in animals with more than three types of color photore- vision results from at least three different opponent mechanisms ceptors. -

Chromatic Function of the Cones D H Foster, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Chromatic Function of the Cones D H Foster, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK ã 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Glossary length. If l is the path length and a(l) is the spectral absorptivity, then, for a homogeneous isotropic CIE, Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage – absorbing medium, A(l)=la(l) (Lambert’s law). The CIE is an independent, nonprofit organization Spectral absorptance a(l) – Ratio of the spectral responsible for the international coordination of radiant flux absorbed by a layer to the spectral lighting-related technical standards, including radiant flux entering the layer. If t(l) is the spectral colorimetry standards. transmittance, then a(l)=1Àt(l). The value of a(l) Color-matching functions – Functions of depends on the length or thickness of the layer. For a wavelength l that describe the amounts of three homogeneous isotropic absorbing medium, fixed primary lights which, when mixed, match a a(l)=1Àt(l)=1À10Àla(l), where l is the path length monochromatic light of wavelength l of constant and a(l) is the spectral absorptivity. Changes in the radiant power. The amounts may be negative. The concentration of a photopigment have the same color-matching functions obtained with any two effect as changes in path length. different sets of primaries are related by a linear Spectral absorptivity a(l) – Spectral absorbance of transformation. Particular sets of color-matching a layer of unit thickness. Absorptivity is a functions have been standardized by the CIE. characteristic of the medium, that is, the Fundamental spectral sensitivities – The color- photopigment. Its numerical value depends on the matching functions corresponding to the spectral unit of length. -

The Diversity and Adaptive Evolution of Visual Photopigments in Reptiles Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7: 352

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Katti, C., Stacey-Solis, M., Anahí Coronel-Rojas, N., Davies, W I. (2019) The Diversity and Adaptive Evolution of Visual Photopigments in Reptiles Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7: 352 https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00352 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-164181 REVIEW published: 19 September 2019 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00352 The Diversity and Adaptive Evolution of Visual Photopigments in Reptiles Christiana Katti 1*, Micaela Stacey-Solis 1, Nicole Anahí Coronel-Rojas 1 and Wayne Iwan Lee Davies 2,3,4,5,6 1 Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2 Center for Molecular Medicine, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 3 Oceans Graduate School, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia, 4 Oceans Institute, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia, 5 School of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia, 6 Center for Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Lions Eye Institute, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia Reptiles are a highly diverse class that consists of snakes, geckos, iguanid lizards, and chameleons among others. Given their unique phylogenetic position in relation to both birds and mammals, reptiles are interesting animal models with which to decipher the evolution of vertebrate photopigments (opsin protein plus a light-sensitive retinal chromophore) and their contribution to vision. -

Color Vision Mechanisms

11 COLOR VISION MECHANISMS Andrew Stockman Department of Visual Neuroscience UCL Institute of Opthalmology London, United KIngdom David H. Brainard Department of Psychology University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 11.1 GLOSSARY Achromatic mechanism. Hypothetical psychophysical mechanisms, sometimes equated with the luminance mechanism, which respond primarily to changes in intensity. Note that achromatic mech- anisms may have spectrally opponent inputs, in addition to their primary nonopponent inputs. Bezold-Brücke hue shift. The shift in the hue of a stimulus toward either the yellow or blue invariant hues with increasing intensity. Bipolar mechanism. A mechanism, the response of which has two mutually exclusive types of out- put that depend on the balance between its two opposing inputs. Its response is nulled when its two inputs are balanced. Brightness. A perceptual measure of the apparent intensity of lights. Distinct from luminance in the sense that lights that appear equally bright are not necessarily of equal luminance. Cardinal directions. Stimulus directions in a three-dimensional color space that silence two of the three “cardinal mechanisms.” These are the isolating directions for the L+M, L–M, and S–(L+M) mech- anisms. Note that the isolating directions do not necessarily correspond to mechanism directions. Cardinal mechanisms. The second-site bipolar L–M and S–(L+M) chromatic mechanisms and the L+M luminance mechanism. Chromatic discrimination. Discrimination of a chromatic target from another target or back- ground, typically measured at equiluminance. Chromatic mechanism. Hypothetical psychophysical mechanisms that respond to chromatic stimuli, that is, to stimuli modulated at equiluminance. Color appearance. Subjective appearance of the hue, brightness, and saturation of objects or lights. -

Cone Fundamentals and CIE Standards

Cone fundamentals and CIE standards Andrew Stockman UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, London, UK Address UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, 11-43 Bath Street, London EC1V 9EL, UK Corresponding author: Stockman, Andrew ([email protected]) Abstract A knowledge of the spectral sensitivities of the long- (L-), middle- (M-) and short- (S-) wavelength-sensitive cone types is vital for modelling human color vision and for the practical applications of color matching and color specification. After being agnostic about defining standard cone spectral sensitivities, the Commission Internationale de l' Éclairage (CIE) has sanctioned the cone spectral sensitivity estimates of Stockman & Sharpe [1] and the associated measures of luminous efficiency [2,3] as “physiologically-relevant” standards for color vision [4,5]. These can be used to model mean normal color vision at the photoreceptor level and postreceptorally. Both LMS and XYZ versions have been defined for 2-deg and 10-deg vision. Built into the standards are corrections for individual differences in macular and lens pigment densities, but individual differences in photopigment optical density and the spectral position of the cone photopigments can also be accommodated [6,7]. Understanding the CIE standard and its advantages is of current interest and importance. 1 Color perception and photopic visual function are inextricably linked to and, indeed, limited by the properties of the three cone photoceptors: the long- (L-), middle- (M-) and short- (S-) wavelength-sensitive cones. This short review covers the derivation of the recent “physiologically- relevant” Commission Internationale de l' Éclairage (CIE) 2006; 2015 cone spectral sensitivities and luminous efficiency functions for 2-deg and 10-deg vision [4,5] and provides background details about cone spectral sensitivities and trichromatic color matching. -

Color Vision and Night Vision Chapter Dingcai Cao 10

Retinal Diagnostics Section 2 For additional online content visit http://www.expertconsult.com Color Vision and Night Vision Chapter Dingcai Cao 10 OVERVIEW ROD AND CONE FUNCTIONS Day vision and night vision are two separate modes of visual Differences in the anatomy and physiology (see Chapters 4, perception and the visual system shifts from one mode to the Autofluorescence imaging, and 9, Diagnostic ophthalmic ultra- other based on ambient light levels. Each mode is primarily sound) of the rod and cone systems underlie different visual mediated by one of two photoreceptor classes in the retina, i.e., functions and modes of visual perception. The rod photorecep- cones and rods. In day vision, visual perception is primarily tors are responsible for our exquisite sensitivity to light, operat- cone-mediated and perceptions are chromatic. In other words, ing over a 108 (100 millionfold) range of illumination from near color vision is present in the light levels of daytime. In night total darkness to daylight. Cones operate over a 1011 range of vision, visual perception is rod-mediated and perceptions are illumination, from moonlit night light levels to light levels that principally achromatic. Under dim illuminations, there is no are so high they bleach virtually all photopigments in the cones. obvious color vision and visual perceptions are graded varia- Together the rods and cones function over a 1014 range of illu- tions of light and dark. Historically, color vision has been studied mination. Depending on the relative activity of rods and cones, as the salient feature of day vision and there has been emphasis a light level can be characterized as photopic (cones alone on analysis of cone activities in color vision. -

Radiometry and Photometry

Radiometry and Photometry Wei-Chih Wang Department of Power Mechanical Engineering National TsingHua University W. Wang Materials Covered • Radiometry - Radiant Flux - Radiant Intensity - Irradiance - Radiance • Photometry - luminous Flux - luminous Intensity - Illuminance - luminance Conversion from radiometric and photometric W. Wang Radiometry Radiometry is the detection and measurement of light waves in the optical portion of the electromagnetic spectrum which is further divided into ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light. Example of a typical radiometer 3 W. Wang Photometry All light measurement is considered radiometry with photometry being a special subset of radiometry weighted for a typical human eye response. Example of a typical photometer 4 W. Wang Human Eyes Figure shows a schematic illustration of the human eye (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1994). The inside of the eyeball is clad by the retina, which is the light-sensitive part of the eye. The illustration also shows the fovea, a cone-rich central region of the retina which affords the high acuteness of central vision. Figure also shows the cell structure of the retina including the light-sensitive rod cells and cone cells. Also shown are the ganglion cells and nerve fibers that transmit the visual information to the brain. Rod cells are more abundant and more light sensitive than cone cells. Rods are 5 sensitive over the entire visible spectrum. W. Wang There are three types of cone cells, namely cone cells sensitive in the red, green, and blue spectral range. The approximate spectral sensitivity functions of the rods and three types or cones are shown in the figure above 6 W. Wang Eye sensitivity function The conversion between radiometric and photometric units is provided by the luminous efficiency function or eye sensitivity function, V(λ). -

The Eye and Night Vision

Source: http://www.aoa.org/x5352.xml Print This Page The Eye and Night Vision (This article has been adapted from the excellent USAF Special Report, AL-SR-1992-0002, "Night Vision Manual for the Flight Surgeon", written by Robert E. Miller II, Col, USAF, (RET) and Thomas J. Tredici, Col, USAF, (RET)) THE EYE The basic structure of the eye is shown in Figure 1. The anterior portion of the eye is essentially a lens system, made up of the cornea and crystalline lens, whose primary purpose is to focus light onto the retina. The retina contains receptor cells, rods and cones, which, when stimulated by light, send signals to the brain. These signals are subsequently interpreted as vision. Most of the receptors are rods, which are found predominately in the periphery of the retina, whereas the cones are located mostly in the center and near periphery of the retina. Although there are approximately 17 rods for every cone, the cones, concentrated centrally, allow resolution of fine detail and color discrimination. The rods cannot distinguish colors and have poor resolution, but they have a much higher sensitivity to light than the cones. DAY VERSUS NIGHT VISION According to a widely held theory of vision, the rods are responsible for vision under very dim levels of illumination (scotopic vision) and the cones function at higher illumination levels (photopic vision). Photopic vision provides the capability for seeing color and resolving fine detail (20/20 of better), but it functions only in good illumination. Scotopic vision is of poorer quality; it is limited by reduced resolution ( 20/200 or less) and provides the ability to discriminate only between shades of black and white. -

Visual Pigments and Oil Droplets from Six Classes of Photoreceptor in the Retinas of Birds J

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Vision Res., Vol. 37, No. 16, pp. 2183-2194, 1997 Pergamon © 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved PH: S0042-6989(97)00026-6 Printed in Great Britain 0042-6989/97 $17.00 + 0.00 Visual Pigments and Oil Droplets from Six Classes of Photoreceptor in the Retinas of Birds J. K. BOWMAKER,*:~ L. A. HEATH,~ S. E. WILKIE,-~ D. M. HUNT~" Received 8 August 1996; in revised form 2 December 1996 Microspectrophotometric examination of the retinal photoreceptors of the budgerigar (shell parakeet), Melopsittacus undulatus (Psittaciformes) and the zebra finch, Taeniopygia guttata (Passeriformes), demonstrate the presence of four, speetrally distinct classes of single cone that contain visual pigments absorbing maximally at about 565, 507, 430-445 and 360-380 nm. The three longer-wave cone classes contain coloured oil droplets acting as long pass filters with cut-offs at about 570, 500-520 and 445 nm, respectively, whereas the ultraviolet-sensitive cones contain a transparent droplet. The two species possess double cones in which both members contain the long- wave-sensitive visual pigment, but only the principal member contains an oil droplet, with cut-off at about 420 nm. A survey of the cones of the pigeon, Columba livia (Columbiformes), confirms the presence of the three longer-wave classes of single cone, but also reveals the presence of a fourth class containing a visual pigment with maximum absorbance at about 409 nm, combined with a transparent droplet. No evidence was found for a fifth, ultraviolet-sensitive receptor. -

Inferring the Retinal Anatomy and Visual Capacities of Extinct Vertebrates

Rowe, M.P. 2000. Inferring the Retinal Anatomy and Visual Capacities of Extinct Vertebrates. Palaeontologia Electronica, vol. 3, issue 1, art. 3: 43 pp., 4.9MB. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2000_1/retinal/issue1_00.htm Copyright: Society of Vertebrate Paleontologists, 15 April 2000 Submission: 18 November 1999, Acceptance: 2 February 2000 INFERRING THE RETINAL ANATOMY AND VISUAL CAPACITIES OF EXTINCT VERTEBRATES M.P. Rowe ABSTRACT One goal of contemporary paleontology is the resto- other terrestrial vertebrates because of the loss of ana- ration of extinct creatures with all the complexity of tomical specializations still retained by members of form, function, and interaction that characterize extant most all tetrapod lineages except eutherian mammals. animals of our direct experience. Toward that end, much Consequently, the largest barrier to understanding vision can be inferred about the visual capabilities of various in extinct animals is not necessarily the nonpreservation extinct animals based on the anatomy and molecular of relevant structures, but rather our deep and largely biology of their closest living relatives. In particular, unrecognized ignorance of visual function in modern confident deductions about color vision in extinct ani- animals. mals can be made by analyzing a small number of genes M.P.Rowe. Department of Psychology, University of in a variety of species. The evidence indicates that basal California, Santa Barbara, CA, 93106, USA. tetrapods had a color vision system that was in some ways more sophisticated than our own. Humans are in a KEY WORDS: eyes, photopigments, dinosaurs, per- poor position to understand the perceptual worlds of ception, color Palaeontologia Electronica—http://www-odp.tamu.edu/paleo 1 PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY: We can deduce that extinct animals had particular (in animals that have them) probably sharpen the spec- soft tissues or behaviors via extant phylogenetic brack- tral tuning of photoreceptors and thus enhance per- eting (EPB, Witmer 1995). -

Application Note

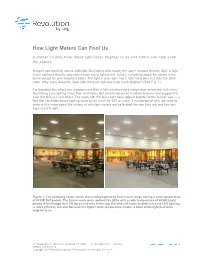

How Light Meters Can Fool Us A primer on why bluer white light looks brighter to us and how it can help save the planet Imagine two identical rooms artificially illuminated with exactly the same amount of white light. A light meter confirms that the two rooms have equal light levels. In fact, everything about the rooms is the same except for one important detail: The light in one room has a little more blue in it than the other room. Why, then, does the room with the bluer light seem so much brighter? (See Fig. 1.) For decades this effect has created more than a little controversy among vision scientists, with many dismissing it as nothing more than an illusion. But recent advances in vision science now support the view that this is a real effect. The room with the bluer light does appear brighter to the human eye — a fact that can help reduce lighting costs by as much as 40% or more. To understand why, we need to know a little more about the history of why light meters are calibrated the way they are and how our eyes react to light. Figure 1: The shopping center above was initially lighted by fluorescent lamps having a color temperature of 4100K (left photo). The fluorescents were replaced by LEDs with a color temperature of 6000K (right photo). Even though the LED lamps use less electricity, the area still looks brighter because LED lighting is more efficient, but also because the higher color temperature creates a bluer white light that looks brighter to us.