Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arcimboldo Challenge

The Arcimboldo Challenge Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Earth, circa 1566, Private collection Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Vertumnus, 1591, Skokloster Castle, Sweden One wouldn’t normally describe Gari Melchers as a common garden-variety portrait painter, but compared to the portraits of the 16th century Italian portrait painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526-1593), most modern portrait paintings are exceedingly dull. For those who have always loved pictorial puzzles and curiosities, Arcimboldo is appreciated for his witty and original grotesques. The mannerist painter possessed a singular imagination, churning out fantastical likenesses of his patrons from carefully orchestrated composite heads based on vegetal, fruit, animate and inanimate themes. Today his celebrated reputation is based entirely on only a dozen or so bizarre pictures. They serve as much more than just painted jokes or illusionism. While he may not have been in the same league as the master painters of his day, his art is a tour de force of the imagination, and his oil paintings are the highly accurate records of a consummate naturalist, incorporating an impressive range of identifiable sea life, botanicals and plants. We thought it might be great fun to see how inspiring his work might be for artists today, especially while we are already looking for something to do during the COVID-19 emergency. Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Spring, Royal Academy, Madrid Gari Melchers Home and Studio is issuing an Arcimboldo Challenge! Artists of all ages are invited to create and submit digital images of their own. Painted Arcimboldo-Style Portrait Or Arcimboldo-Style Portrait Constructed Out of Three- Dimensional Objects Here is what you need to do: Paint or construct your 2-D portrait out of any media, watercolor, acrylic, magazine clippings, etc. -

Giuseppe Arcimboldo's Composite Portraits and The

Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Composite Portraits and the Alchemical Universe of the Early Modern Habsburg Court (1546-1612) By Rosalie Anne Nardelli A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Art History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada July, 2014 Copyright © Rosalie Anne Nardelli, 2014 Abstract At the Renaissance noble court, particularly in the principalities of the Holy Roman Empire, alchemical pursuits were wildly popular and encouraged. By the reign of Rudolf II in the late sixteenth century, Prague had become synonymous with the study of alchemy, as the emperor, renowned for his interest in natural magic, welcomed numerous influential alchemists from across Europe to his imperial residence and private laboratory. Given the prevalence of alchemical activities and the ubiquity of the occult at the Habsburg court, it seems plausible that the art growing out of this context would have been shaped by this unique intellectual climate. In 1562, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, a previously little-known designer of windows and frescoes from Milan, was summoned across the Alps by Ferdinand I to fulfil the role of court portraitist in Vienna. Over the span of a quarter-century, Arcimboldo continued to serve faithfully the Habsburg family, working in various capacities for Maximilian II and later for his successor, Rudolf II, in Prague. As Arcimboldo developed artistically at the Habsburg court, he gained tremendous recognition for his composite portraits, artworks for which he is most well- known today. Through a focused investigation of his Four Seasons, Four Elements, and Vertumnus, a portrait of Rudolf II under the guise of the god of seasons and transformation, an attempt will be made to reveal the alchemical undercurrents present in Arcimboldo’s work. -

Masterpiece: Autumn, 1573 by Giuseppe Arcimboldo

Masterpiece: Autumn, 1573 by Giuseppe Arcimboldo Pronounced: Gee-you-she-pay Ar-cheem bowl-doh Keywords: portrait, texture, collage Grade: Kindergarten Month: November Activity: You are what you eat… Meet the Artist: He was born in Italy in 1527 to an influential family.He eventually becoming well known for his paintings. Many famous and wealthy people paid him to paint their portraits, or pictures of themselves. With time, he became a very odd portraitist. He adopted an odd and short lived style called mannerism. This style was in insult to the High Renaissance painters of the day, but he still got work. He became particularly famous after his series called seasons. Summer is one of them. This series shows a man made up of whatever that season had to offer. So, in Autumn, the man is made up of fruit from the fall, such as apples, grapes, and pumpkins. In Winter, The man is made up of a tree that has shed all of it’s leaves. He chose specific textures in the plants to portray people. His work resembles modern art. It could easily be a collage, or a painting made up of pieces of paper, put together to create art. He lived a busy and full life, dying in 1593. Possible Questions: o What items can you identify in Autumn? o Does it look textured to you, does it look like you could feel the skins of the fruit and vegetables? o Does it look like a painting that is several of hundreds of years old, or does it look like it could be an illustration in one of your books? o Do you like it? Why? Why not? o Do you think it is creative? o Would you like a portrait made of you in this style? Masterpiece: Autumn, 1573 by Giuseppe Arcimboldo Activity: You are what you eat… Materials Needed: White paper, food color copies, scissors, pencils, glue sticks Process: 1. -

Giuseppe Arcimboldo's Grilli: Humor and Magic in Genre Portraits

Cultural and Religious Studies, February 2019, Vol. 7, No. 2, 57-76 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2019.02.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Grilli: Humor and Magic in Genre Portraits Liana De Girolami Cheney Universidad de Coruña, Spain This essay examines one aspect of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s portraiture: His genre depictions where he expands the art of illusionism or magic visualization into grilli (intellectual whims) and teste composte (composite heads). These images of reversible portraits of genre scenes, caricatural conceits, and visual puns are seen in The Cook or The Chef reversed as The Bowl of Meats of 1570 at the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm; The Vegetable Gardener reversed as The Bowl of Vegetables of 1590 at the Museo Civico “Ala Ponzone”, Cremona; and Il Frutaio, The Fruit Vendor reversed as The Basket of Fruits of 1591, at the French & Company Gallery in New York. In his imagery, Arcimboldo focuses on the paradoxical meaning of objects, “what if?” adding a sense of ambiguity and mystery to his art. Is Arcimboldo teasing the viewer with a Mannerist flare, or is he composing or implying another type of intellectual conceit? Ultimately, Arcimboldo invents a new type of genre: the emblematic humorous portrait. Keywords: composite heads, grilli, humor, delight, innuendo, symbolism, mannerism, Milan, School of Prague, art theory, grotesque The Mannerist painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527-1593) was born in Milan in 1527, the son of artist Biagio Arcimboldo and Chiara Parisi (Kaufmann, 1976; Zeri, 2001/1998; Kaufmann, 2010; Cheney, 2008/2013/2015; Baltrusaïtis, 1987; Ferino-Pagden, 2007; Ferino-Pagden, 2018; Geiger, 1954).1 He died on July 11, 1593, in his native city (see Figures 1, 2, and 3). -

Precious Textiles Have Always Played an Important Role As a Medium Of

FASHION SHOW Precious textiles have always played an important role as a PRINCELY WARDROBES medium of representation and as a means of expressing high OF THREE CENTURIES social rank. Only an elite segment of the public could afford exquisite textiles and dress in the latest fashion. Portraits in which personalities of standing had themselves depicted in SPECIAL EXHIBITION expensive clothing today give us insightful information about JUNE 17 TO OCTOBER 3, 2021 the original condition of these wardrobes. Their ingenuity and the exquisite materials used continue to captivate viewers. For the first time, a selection of paintings by renowned artists from the Habsburg Portrait Gallery kept at Ambras Castle, from Giuseppe Arcimboldo to Diego Velázquez, is placed at the centre of an exhibition, focusing on fashions from the Renaissance to the Baroque period. What are the sitters in these portraits wearing, how are their clothes obtained, and what do they communicate to the viewer? The show will be enriched by precious original clothing of which, due to their fragility, only a few are preserved. On dis- ILLUSTRATION: (DETAIL) ARCHDUCHESS MARIA MAGDALENA (1587–1631). FRANS play are, for example, the bridal robe of Duke August of Sa- POURBUS THE YOUNGER, C.1603/1604 xony from 1548, a doublet from 1555 and a velvet cloak from KUNSTHISTORISCHES MUSEUM VIENNA, 1560. Headdresses and shoes, accessories such as collars, PICTURE GALLERY, INV. NO. 3385 (SCHLOSS AMBRAS INNSBRUCK) gloves and fans, as well as exquisite pieces of jewelry, have © KHM-MUSEUMSVERBAND also been lent to the exhibition by international museums. Schloss Ambras Innsbruck, Schlossstraße 20, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria [email protected], Tel.: +43 1 525 24 - 4802, www.schlossambras-innsbruck.at, FASHION SHOW An essential element of the exhibition is the inclusion of new PRINCELY WARDROBES media: film visualisations tell stories behind the pictures and put OF THREE CENTURIES fashion under the microscope, right down to the last detail. -

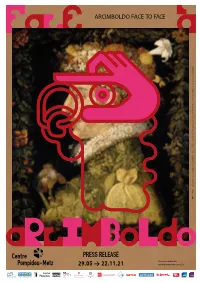

ARCIMBOLDO FACE to FACE I Z Z I R E B

Mécène fondateur 29.05 PRESS RELEASE → A R 22.11.21 C I M B O L D O F A C E TOFACE # c e f a nt c e r e a p a r o c m i m p b i d o o l d u o - m e t z . f r M/M (PARIS) Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Les Quatre Saisons, Le Printemps , 1573 ; huile sur toile, 76 × 63,5 cm ; Paris, musée du Louvre, département des Peintures. Photo ©RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Jean-Gilles Berizzi ARCIMBOLDO FACE TO FACE CONTENTS 1. GENERAL PRESENTATION .................................................................5 2. GIUSEPPE ARCIMBOLDO ...................................................................8 3. ARCIMBOLDO FACE TO FACE ..........................................................11 4. EXHIBITION LAYOUT .......................................................................18 5. FORUM .............................................................................................24 6. LISTE OF ARTISTS ............................................................................26 7. LISTE OF LENDERS ..........................................................................28 8. CATALOGUE & PUBLICATIONS ..........................................................30 9. RELATED PROGRAMME ....................................................................33 10. YOUNG PEOPLE AND EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES ............................38 11. PARTNERS......................................................................................40 12. PRESS VISUALS .............................................................................46 3 ARCIMBOLDO FACE TO FACE Mario -

The Wonderful World of the Renaissance

The wonderful world of the Renaissance CASTLE AMBRAS INNSBRUCK Castle Ambras Innsbruck is one of Innsbruck’s most popular attractions. The picturesque Renaissance castle, the precious art collections, and the magnificent grounds are a delightful experience for all visitors. THE HISTORY OF THE CASTLE The provincial sovereign of Tyrol, Archduke Ferdinand II (1529 – 1595), son of Emperor Ferdinand I, ordered that the mediaeval fortress at Ambras be turned into a Renaissance castle for his wife Philippine Welser. The daughter of a wealthy Augsburg patrician, Philippine was not permitted to reside at the Hofburg palace as her morganatic marriage – while valid according to church law – was considered ‘below the Emperor’s station’. Moreover, in the 16th century, it had become fashionable to establish a magnificent summer residence. After her death in 1580 Ferdinand commissioned the construction of a unique museum complex for his world-famous art collections next to the picturesque Upper Castle with its wonderful views over Innsbruck. As a prominent precursor of our modern-day museums, it has been preserved at its original site to this day. The collections at Castle Ambras are part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, one of the world’s foremost museums. The imposing Renaissance castle – a gift from Ferdinand to his spouse Philippine THE LOWER CASTLE ARCHDUKE FERDINAND’S MAGNIFICENT As they pass through the castle gate, visitors enter the idyllic castle gardens, SUITS OF ARMOUR which contain Archduke Ferdinand II’s famous Rüstkammern, or Armouries. They include rare examples of 15th century jousting armour from the col- lections of Emperor Maximilian I, suits of armour of famous 16th century commanders, the Archduke’s private armour, the armour of the court of Innsbruck, and weapons from the Thirty Years’ War. -

Arcimboldo's Vertumnus: a Portrait of Rudolf II

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Arcimboldo’s Vertumnus: A Portrait of Rudolf II Whoever you are, looking at me, . for on the outside A strange deformed image, I seem a monster, and on the inside With a laugh on your lips I hide a kingly image, and That flashes in your eyes A heavenly resemblance... And stamps your face Holy, invincible, supreme, august With novel happiness And righteous Rudolf, honour of Austria... Gregorio Comanini, The Figino, or on the Purpose of Painting, 15911(p19,24) IUSEPPE ARCIMBOLDO and for Earth, various animals; each of the elements. So pleased was Emperor (1527-1593) was a cre- them signifies a human attribute. For Maximilian that he had himself cos- ative force in the courts of example, the crafty fox is shown at the tumed as Arcimboldo’s Winter in a sea- Maximilian II (1527- sonal celebration. Rudolf hung copies of G1576) and his son Rudolf II (1552- paintings of the Seasons in his bedroom 1612), Habsburg emperors of the Holy and ordered additional copies to give to Roman Empire in Vienna and Prague.2,3 leading dignitaries. Arcimboldo also Originally recruited as a court painter, made composite portraits of individu- Arcimboldo saw his role rapidly expand als of the royal household. The Librar- to arranging lavish court ceremonies ian (Figure 1) depicts the curator of the (royal marriages, festivities for a royal imperial collections and historian, Wolf- crowning), designing costumes and gang Lazius (1514-1565), composed in masques for balls, and organizing tour- books. His hair is shown as an inverted naments. -

The Center for Arts & Crafts

The Center for Arts & Crafts Juice, oil painting by Jesse McCreery Drawing and Painting BFA and Art Education major at Penn State studentaffairs.psu.edu/hub/craftcenter SPRING 2020 Schedule of CREATE AT HOME - Vol. 2 SERVING PENN STATE STUDENTS, STAFF AND FACULTY An outreach program of the Penn State Student Activities, Student Engagement Programs University Park Campus CONTENTS HISTORY General Info- page 1 History- page 2 The Center for Arts and Crafts (CFAC) has a long history of providing an artistic outlet for Stay Home Workshops- page 3 Penn State students, staff and faculty. It all began in the 1970s and was located on the third floor of the Hetzel Union Building (HUB). Approximately 40 years later, the Center for Arts and Crafts is now located in the lower level of the Ritenour Building and the Ceramics Studio is located in the lower level of the HUB-Robeson Center. At the Center for Arts and Crafts, learn new artistic skills or improve current skill levels; design, create and appreciate arts, crafts and performance arts; and develop creative thinking, creative expression, and problem solving. The CFAC provides a wide variety of creative opportunities and offers relaxation and enjoyment through classes, workshops, community outreach events and exhibits. GENERAL INFO The Center for Arts and Crafts Student Activities Student Affairs 003 Ritenour Building The Pennsylvania State University Center Phone: (814) 863-0611 Registration Information: (814) 865-9278 Stephanie Gush, program manager [email protected], (814) 863-0611 Mandi Gatto, administrative support assistant [email protected], (814) 863-0611 Cover photo: Juice, oil painting by Jesse McCreery Classes are subsidized for Penn State students by your Student Initiated Fee and are offered at reduced fees to those with a valid and current Penn State Student ID! Class fees for Penn State students may vary from semester to semester depending upon allocated funds. -

Arcimboldo 1526 – 1593 Nature and Fantasy

Arcimboldo 1526 – 1593 nature and fantasy national gallery of art september 19, 2010 – january 9, 2011 fig. 1 fig. 2 fig. 1 giuseppe arcimboldo, Winter, 1563 fig. 2 giuseppe arcimboldo, Spring, 1563 fig. 3 giuseppe arcimboldo, Summer, 1563 fig. 3 introduction Nature Studies Anyone looking at Arcimboldo’s composite heads for the first time feels surprised, startled, and bewildered; our gaze moves The rise of the new sciences of botany, horticulture, and back and forth between the overall human form and the rich- zoology in the sixteenth cen- ness of individual details until we get the joke and find ourselves tury focused artists’ attention amused, delighted, or perhaps even repelled. Any transforma- on the natural world to an extent not seen since antiquity. tion or manipulation of the human face attracts attention, but During the Renaissance, the effect is accentuated when we are confronted with monsters a renewed interest in the where, instead of eyes, mouths, noses, and cheeks, we find flow- natural world had led artists ers or cherries, peas, cucumbers, peaches, broken branches, to depict animals and plants with great accuracy, as seen and much else (figs. 1 – 3). Arcimboldo’s paintings stimulate in Dürer’s Tuft of Cowslips opposing, irreconcilable interpretations of what we are seeing (fig. 8). The study of flora and and thus are paradoxical in the truest sense of the word. fauna intensified as a result of Soon forgotten after his death, Arcimboldo was rediscov- the sixteenth-century voyages of exploration and discovery ered in the 1930s when the director of the Museum of Modern to the New World, Africa, and Art in New York, Alfred H. -

Naveed Bork Memorial Tournament

Naveed Bork Memorial Tournament: Tippecanoe and Tejas Too By Will Alston, with contributions from Itamar Naveh-Benjamin and Benji Nguyen, but not Joey Goldman Packet 7 1. This person commissioned a copy of a painting of Adam and Eve to deceive locals in Nuremburg after having the work hauled off, and acquired the world’s largest medieval manuscript, the Codex Gigas, from a monastery in Goumov. This person sponsored Tyrolian expeditions by Roelant Savery to study and draw fauna and commissioned bawdy nudes illustrating this person’s esoteric philosophical ideas, such as The Triumph of Wisdom by Bartholomeus Spranger. This person built a new wing of a castle to house Europe’s greatest Kunstkammer, or (*) “cabinet of curiosities.” Art historians often use an adjectival form of this ruler’s name to describe late styles of Northern Mannerism that he promoted in Prague. Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Vertumnus is a depiction of this ruler, whose crown was given to rulers of the Austrian Empire. For 10 points, name this art-loving Holy Roman Emperor who died in 1612. ANSWER: Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor [prompt on Rudolfine Mannerism by asking “Rudolf of which number?”] 2. A folktale about a demon causing two objects to break inside one of these places is celebrated by the folk festival of Kanamara Matsuri, which is based on an Ainu folktale. In various Indian religions, this sort of place is used as an analogy for the states in which a person can be reborn, such as manusya, deva, and rakshasa forms. In Hawaiian myth, a movable one of these locations was used by Kapo to lure the hog-headed god Kamapua’a away from Pele. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Balanced Wonder: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Role of Wonder in Human Flourishing PEDERSEN, JAN,BJERGGAARD,WAKATSUKI How to cite: PEDERSEN, JAN,BJERGGAARD,WAKATSUKI (2015) Balanced Wonder: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Role of Wonder in Human Flourishing, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11406/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 BALANCED WONDER: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Role of Wonder in Human Flourishing By Jan Bjerggaard Wakatsuki Pedersen Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Medicine, Pharmacy and Health Durham University 2015 To my family Mai Wakatsuki Pedersen, Iris (2015). Table of Contents Abstract 1 List of Illustrations 2 Acknowledgement 3 Introduction 5 1. The Lure of Wonder 15 1.1 The Name and Root of Wonder 23 1.2 A History of Wonder 26 1.3 Provisional Taxonomy of Altered States 47 1.4 Enemies of Wonder 64 1.5 Towards a Preliminary Understanding of Wonder 68 2.