Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giuseppe Arcimboldo's Composite Portraits and The

Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Composite Portraits and the Alchemical Universe of the Early Modern Habsburg Court (1546-1612) By Rosalie Anne Nardelli A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Art History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada July, 2014 Copyright © Rosalie Anne Nardelli, 2014 Abstract At the Renaissance noble court, particularly in the principalities of the Holy Roman Empire, alchemical pursuits were wildly popular and encouraged. By the reign of Rudolf II in the late sixteenth century, Prague had become synonymous with the study of alchemy, as the emperor, renowned for his interest in natural magic, welcomed numerous influential alchemists from across Europe to his imperial residence and private laboratory. Given the prevalence of alchemical activities and the ubiquity of the occult at the Habsburg court, it seems plausible that the art growing out of this context would have been shaped by this unique intellectual climate. In 1562, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, a previously little-known designer of windows and frescoes from Milan, was summoned across the Alps by Ferdinand I to fulfil the role of court portraitist in Vienna. Over the span of a quarter-century, Arcimboldo continued to serve faithfully the Habsburg family, working in various capacities for Maximilian II and later for his successor, Rudolf II, in Prague. As Arcimboldo developed artistically at the Habsburg court, he gained tremendous recognition for his composite portraits, artworks for which he is most well- known today. Through a focused investigation of his Four Seasons, Four Elements, and Vertumnus, a portrait of Rudolf II under the guise of the god of seasons and transformation, an attempt will be made to reveal the alchemical undercurrents present in Arcimboldo’s work. -

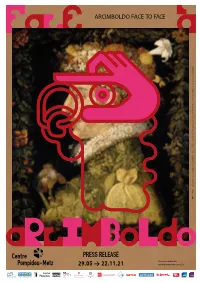

ARCIMBOLDO FACE to FACE I Z Z I R E B

Mécène fondateur 29.05 PRESS RELEASE → A R 22.11.21 C I M B O L D O F A C E TOFACE # c e f a nt c e r e a p a r o c m i m p b i d o o l d u o - m e t z . f r M/M (PARIS) Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Les Quatre Saisons, Le Printemps , 1573 ; huile sur toile, 76 × 63,5 cm ; Paris, musée du Louvre, département des Peintures. Photo ©RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Jean-Gilles Berizzi ARCIMBOLDO FACE TO FACE CONTENTS 1. GENERAL PRESENTATION .................................................................5 2. GIUSEPPE ARCIMBOLDO ...................................................................8 3. ARCIMBOLDO FACE TO FACE ..........................................................11 4. EXHIBITION LAYOUT .......................................................................18 5. FORUM .............................................................................................24 6. LISTE OF ARTISTS ............................................................................26 7. LISTE OF LENDERS ..........................................................................28 8. CATALOGUE & PUBLICATIONS ..........................................................30 9. RELATED PROGRAMME ....................................................................33 10. YOUNG PEOPLE AND EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES ............................38 11. PARTNERS......................................................................................40 12. PRESS VISUALS .............................................................................46 3 ARCIMBOLDO FACE TO FACE Mario -

Arcimboldo 1526 – 1593 Nature and Fantasy

Arcimboldo 1526 – 1593 nature and fantasy national gallery of art september 19, 2010 – january 9, 2011 fig. 1 fig. 2 fig. 1 giuseppe arcimboldo, Winter, 1563 fig. 2 giuseppe arcimboldo, Spring, 1563 fig. 3 giuseppe arcimboldo, Summer, 1563 fig. 3 introduction Nature Studies Anyone looking at Arcimboldo’s composite heads for the first time feels surprised, startled, and bewildered; our gaze moves The rise of the new sciences of botany, horticulture, and back and forth between the overall human form and the rich- zoology in the sixteenth cen- ness of individual details until we get the joke and find ourselves tury focused artists’ attention amused, delighted, or perhaps even repelled. Any transforma- on the natural world to an extent not seen since antiquity. tion or manipulation of the human face attracts attention, but During the Renaissance, the effect is accentuated when we are confronted with monsters a renewed interest in the where, instead of eyes, mouths, noses, and cheeks, we find flow- natural world had led artists ers or cherries, peas, cucumbers, peaches, broken branches, to depict animals and plants with great accuracy, as seen and much else (figs. 1 – 3). Arcimboldo’s paintings stimulate in Dürer’s Tuft of Cowslips opposing, irreconcilable interpretations of what we are seeing (fig. 8). The study of flora and and thus are paradoxical in the truest sense of the word. fauna intensified as a result of Soon forgotten after his death, Arcimboldo was rediscov- the sixteenth-century voyages of exploration and discovery ered in the 1930s when the director of the Museum of Modern to the New World, Africa, and Art in New York, Alfred H. -

Naveed Bork Memorial Tournament

Naveed Bork Memorial Tournament: Tippecanoe and Tejas Too By Will Alston, with contributions from Itamar Naveh-Benjamin and Benji Nguyen, but not Joey Goldman Packet 7 1. This person commissioned a copy of a painting of Adam and Eve to deceive locals in Nuremburg after having the work hauled off, and acquired the world’s largest medieval manuscript, the Codex Gigas, from a monastery in Goumov. This person sponsored Tyrolian expeditions by Roelant Savery to study and draw fauna and commissioned bawdy nudes illustrating this person’s esoteric philosophical ideas, such as The Triumph of Wisdom by Bartholomeus Spranger. This person built a new wing of a castle to house Europe’s greatest Kunstkammer, or (*) “cabinet of curiosities.” Art historians often use an adjectival form of this ruler’s name to describe late styles of Northern Mannerism that he promoted in Prague. Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Vertumnus is a depiction of this ruler, whose crown was given to rulers of the Austrian Empire. For 10 points, name this art-loving Holy Roman Emperor who died in 1612. ANSWER: Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor [prompt on Rudolfine Mannerism by asking “Rudolf of which number?”] 2. A folktale about a demon causing two objects to break inside one of these places is celebrated by the folk festival of Kanamara Matsuri, which is based on an Ainu folktale. In various Indian religions, this sort of place is used as an analogy for the states in which a person can be reborn, such as manusya, deva, and rakshasa forms. In Hawaiian myth, a movable one of these locations was used by Kapo to lure the hog-headed god Kamapua’a away from Pele. -

Music 3-6: Playing the Mind

happy confused MEDIA ARTS 3-8: MIND THE SELFIE! National Portrait Gallery, Portrait of a OTHER RESOURCES Nation, ‘Australian Schools Portrait • Cheap cameras or digital devices Project, Years 5 to 8’ that students can use to take photos. For older students http://www.portrait.gov.au/ • Access to clean sand, rice and/or The Australian Centre for Photography portraitofanation/ fallen leaves and SBS Teacher Notes on ‘School National Gallery of Art, Education, • Historical selfies dating back to the Selfie’ ‘Who Am I? Self-Portraits’ 1800s http://www.sbs.com.au/sites/sbs. http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/ com.au.home/files/school_selfie_-_ education/teachers/lessons-activities/ • Computers and photography teachers_notes_-_high_res.pdf self-portraits.html software IPad Art Room, Blog post “Don’t hate What is Modern Art? FEED THE MIND WITH the selfie” https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_ http://www.ipadartroom.com/dont- learning/themes/what-is-modern-art/ DreamBIG CHILDREN’S hate-the-selfie/ modern-portraits FESTIVAL PROGRAM Portrait Photography – useful for An internet search on the Paul Adelaide International Youth Film details about light Getty Museum will reveal useful Festival https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrait_ education resources for portraits that A Taste of Unity photography can easily be adapted to the making E-Bully Selfies or self-portraiture – and responding of the Australian Gone Viral professional photographers Francesca Curriculum: The Arts. Woodman, Douglas Prince Into the Jungle http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/ Movie Music Making woodman-untitled-ar00351 3D Creature Exchange http://www.douglasprince.com/ The Listies 6D p690616609 MUSIC 3-6: PLAYING THE MIND INQUIRY QUESTION Students collaborate to plan and make Level 4: Assess and test options to identify the most effective solution How can I support students to: artworks that communicate ideas. -

GIUSEPPE ARCIMBOLDO (Or ARCIMBOLDI) Italian Painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo Was an Italian Painter

Insegnante Laura Zuliani Scuola Primaria di Faedis (UD) Istituto Comprensivo di Faedis (UD) - Italia Progetto Erasmus Plus 2016-1-IT02-KA101-022756 Titolo Progetto: “T.I.E (Training in Europe)” Corso strutturato di metodologia CLIL frequentato a Cheltenham (UK) dal 14 al 21 maggio 2017 GIUSEPPE ARCIMBOLDO (or ARCIMBOLDI) Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo was an Italian painter. He was born in Milan on 5th April 1526. He died in Milan on 11st July 1593. Why can we find this self- portrait in the Národní Gallery ? in Prague? Self-portrait, Národní Gallery - Prague Arcimboldo began to paint in Milan, where he became famous. In 1562 he moved to the court of Ferdinand I in Vienna. Later he left Vienna for Prague where he was the court painter for Maximilien II and his son Rudolph II. In Prague the artist lived for many years working as a court portraitist, court decorator and costume designer. While in Prague, he manifested his unmistakeable style. This is one of his paintings. At first sight this seems like a very normal still life… … there are a lot of vegetables and fruits: an onion, some mushrooms, garlic, nuts, chestnuts… …but if you turn it upside down… … or Vegetables in a bow (… still life) Ala Ponzone Civic Museum - Cremona Everything changes completely!!!! Now you can see a face!!!! Do you agree with me? Nose: radish Mouth: mushrooms Eyes: nuts Cheek: onion Ear: radish Beard: chicory Hat: bowl Greengrocer or Vegetables in a bowl (reversible still life) Ala Ponzone Civic Museum - Cremona Arcimboldo’s paintings are anthropomorphic compositions, representing human figures! Reversible fruit basket - French & Company - New York. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Adomo's physiognomical image of Mahler: the convergence of music, painting, and language McLaughlin, Rebecca How to cite: McLaughlin, Rebecca (2009) Adomo's physiognomical image of Mahler: the convergence of music, painting, and language, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2298/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author or the university to which it was 1 submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it should be acknowledged. Adorno's Physiognomical Image of Mahler: the convergence of Music, Painting, and Language By Rebecca McLaughlin 2 6 JAN 2009 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract- · - - - - - - - - -