September 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Can Hear Music

5 I CAN HEAR MUSIC 1969–1970 “Aquarius,” “Let the Sunshine In” » The 5th Dimension “Crimson and Clover” » Tommy James and the Shondells “Get Back,” “Come Together” » The Beatles “Honky Tonk Women” » Rolling Stones “Everyday People” » Sly and the Family Stone “Proud Mary,” “Born on the Bayou,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Green River,” “Traveling Band” » Creedence Clearwater Revival “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” » Iron Butterfly “Mama Told Me Not to Come” » Three Dog Night “All Right Now” » Free “Evil Ways” » Santanaproof “Ride Captain Ride” » Blues Image Songs! The entire Gainesville music scene was built around songs: Top Forty songs on the radio, songs on albums, original songs performed on stage by bands and other musical ensembles. The late sixties was a golden age of rock and pop music and the rise of the rock band as a musical entity. As the counterculture marched for equal rights and against the war in Vietnam, a sonic revolution was occurring in the recording studio and on the concert stage. New sounds were being created through multitrack recording techniques, and record producers such as Phil Spector and George Martin became integral parts of the creative process. Musicians expanded their sonic palette by experimenting with the sounds of sitar, and through sound-modifying electronic ef- fects such as the wah-wah pedal, fuzz tone, and the Echoplex tape-de- lay unit, as well as a variety of new electronic keyboard instruments and synthesizers. The sound of every musical instrument contributed toward the overall sound of a performance or recording, and bands were begin- ning to expand beyond the core of drums, bass, and a couple guitars. -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Faculty Recital the Webster Trio

) FACULTY RECITAL THE WEBSTER TRIO r1 LEONE BUYSE, flute ·~ MICHAEL WEBSTER, clarinet ROBERT MOEL/NG, piano Friday, September 19, 2003 8:00 p.m. Lillian H Duncan Recital Hall RICE UNNERSITY PROGRAM Dance Preludes Witold Lutoslawski . for clarinet and piano (1954) (1913-1994) Allegro molto ( Andantino " Allegro giocoso Andante Allegro molto Dolly, Op. 56 (1894-97) (transcribed for Gabriel Faure flute, clarinet, and piano by M. Webster) (1845-1924) Berceuse (Lullaby) Mi-a-ou Le Jardin de Dolly (Dolly's Garden) Ketty-Valse Tendresse (Tenderness) Le pas espagnol (Spanish Dance) .. Children of Light Richard Toensing ~ for flute, clarinet, and piano (2003, Premiere) (b. 1940) Dawn Processional Song ofthe Morning Stars The Robe of Light Silver Lightning, Golden Rain Phos Hilarion (Vesper Hymn) INTERMISSION Round Top Trio Anthony Brandt for flute, clarinet, and piano (2003) (b. 1961) Luminall Kurt Stallmann for solo flute (2002) (b. 1964) Eight Czech Sketches (1955) KarelHusa (transcribed for flute, clarinet, (b. 1921) and piano by M. Webster) Overture Rondeau Melancholy Song Solemn Procession Elegy Little Scherzo Evening Slovak Dance j PROGRAM NOTES Dance Preludes . Witold Lutoslawski Witold Lutoslawski was born in Warsaw in 1913 and became the Polish counterpart to Hunga,y's Bela Bart6k. Although he did not engage in the exhaustive study of his native folk song that Bart6k did, he followed Bart6k's lead in utilizing folk material in a highly individual, acerbic, yet tonal fash .. ion. The Dance Preludes, now almost fifty years old, appeared in two ver sions, one for clarinet, harp, piano, percussion, and strings, and the other for clarinet and piano. -

The Ithacan, 1990-10-04

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1990-91 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 10-4-1990 The thI acan, 1990-10-04 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1990-10-04" (1990). The Ithacan, 1990-91. 6. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91/6 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1990-91 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. • ~ I :ii Ithaca. wetlands' construction Fairyland shattered by adminis Midnight Oil gives held Up tration indecisiveness anticlimactic performance .•• page 6 ... page 7 ... page 9 ,, ... ,,1,'-•y•'• ,,1. :CJ<,·')• ..... The ITHACAN The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Vol. 58, No. 6 October 4, 1990 24 pages Free Arrests. conti:n-ue despite warning lcm." 'crackdown' on parties on South neighborhoods. 75 student arrests over--past three weeks Dave Maley, Manager of Public Hill. McEwen said that he needs at "I expect students to think of this By Joe Porletto Holt, head of the IC office of cam Information for IC, said that when least one additional officer, but there area as their home," McEwen said. The weekend of Sept. 28 resulted pus"' safety, addressed the party students are off-campus they must isn't room in the city budget for it McEwen said that studcn ts wouldn't in 26 arrests of college students on proolem. -

1 Musik Spezial

1 Musik Spezial - Radiophon 21.03 bis 22.00 Uhr Sendung: 31.01.2013 Von Harry Lachner Musikmeldung 1. A Little Place Called Trust The Paper Chase (John Congleton) 28101-2 CD: Hide The Kitchen Knives 2. Ceremonial Magic II John Zorn (John Zorn) Tzadik TZ 8092 CD: Music and Its Double 3. Black Angels - I. Departure Quatuor Diotima (George Crumb) Naive 5272 CD: American Music 4. L.A. Confidential Jerry Goldsmith (Goldsmith) Restless 0187-72946-2 CD: LA Confidential 5. The Prophecy John Zorn (John Zorn) Tzadik TZ 8303 CD: A Vision in Blakelight 6. Room 203 Graham Reynolds (Graham Reynolds) Lakeshore 33863 CD: A Scanner Darkly 7. Fantasie For Horns II Hildegard Westerkamp (Hildewgard Westerkamp) Empreintes Digitales IMED 9631 CD: Transformations 8. Hier und dort Ernst Jandl, Christian Muthspiel (Ernst Jandl, Christian Muthspiel) Universal 0602517784901 (LC: 12216) CD: für und mit ernst 9. Tristan Eric Schaefer (Richard Wagner) ACT 9543-2 CD: Who is afraid of Richard W.? 10. Je ne pense kanous Hélène Breschand, Sylvain Kassap (Hélène Breschand, Sylvain Kassap) D'Autres Cordes dac 311 CD: Double-Peine 11. Harbour Symphony Hildegard Westerkamp (Hildegard Westerkamp) Empreintes Digitales IMED 9631 CD: Transformations 2 12. Soudain l'hiver dernier Hélène Breschand, Sylvain Kassap (Hélène Breschand, Sylvain Kassap) D'Autres Cordes dac 311 CD: Double-Peine 13. Voyage en Egypte Paul Bowles (Paul Bowles, Bill Laswell) Meta Records MTA9601 CD: Baptism of Solitude 14. Floundering Shelley Hirsch, Simon Ho (Shelley Hirsch, Simon Ho) Tzadik 7638 CD: Where Were You, Then? 15. Flea Bite Nurse with Wound (Steven Stapleton) UD 032 CD CD: A Sucked Orange 16. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Michael Franti Isnot

Twisting and turning at Bonnaroo 2003 “I felt scared every second fire on your car, because I was there,” says a bare- they’re so paranoid of foot and shirtless Michael people surveilling for Franti, contorting his mid- car-bombing.” MICHAEL section on a stretch of In between twisting sun-soaked concrete. It’s himself like licorice, the a little before two o’clock dreadlocked Franti has in the afternoon and Franti been talking about waking FRANTI has just gotten up, having up the morning after the emerged from Spearhead’s invasion of Iraq, finding a tour bus for his daily yoga television and seeing session. After driving all- politicians and generals ISNOT night from yesterday’s stop discussing the political and at the All Good festival in economic costs of the West Virginia, the Big war, but never the human Summer Classic tour has cost. Right now, he’s talk- brought the band to the ing about his experience sprawling, evergreen making I Know I’m Not Blossom Music Center in Alone—the documentary Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio. film he made while visit- ing Iraq, Israel, The West ALONE Bank and the Gaza Strip. He has a new album, a new film about the Middle East, and a new life “It was the most power- ful experience of my life,” after burying old ghosts (oh, and he’s still full of righteous rebellion) he says, sweat beading on his forehead. “That and In between yoga positions, having my sons.” by Wes Orshoski Franti is sharing memories Watching a rough cut of his trip to Iraq. -

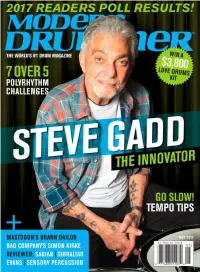

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Top 12 Soul Jazz and Groove Releases of 2006 on the Soul Jazz Spectrum

Top 12 Soul Jazz and Groove Releases of 2006 on the Soul Jazz Spectrum Here’s a rundown of the Top 12 albums we enjoyed the most on the Soul Jazz Spectrum in 2006 1) Trippin’ – The New Cool Collective (Vine) Imagine a big band that swings, funks, grooves and mixes together R&B, jazz, soul, Afrobeat, Latin and more of the stuff in their kitchen sink into danceable jazz. This double CD set features the Dutch ensemble in their most expansive, challenging effort to date. When you can fill two discs with great stuff and nary a dud, you’re either inspired or Vince Gill. These guys are inspired and it’s impossible to not feel gooder after listening to Trippin.’ Highly recommended. 2) On the Outset – Nick Rossi Set (Hammondbeat) It’s a blast of fresh, rare, old air. You can put Rossi up there on the Hammond B3 pedestal with skilled survivors like Dr. Lonnie Smith and Reuben Wilson. This album is relentlessly grooving, with no ballad down time. If you think back to the glory days of McGriff and McDuff, this “set” compares nicely. 3) The Body & Soul Sessions – Phillip Saisse Trio (Rendezvous) Pianist Saisse throws in a little Fender Rhodes and generally funks up standards and covers some newer tunes soulfully and exuberantly. Great, great version of Steely Dan’s “Do It Again.” Has that feel good aura of the old live Ramsey Lewis and Les McCann sides, even though a studio recording. 4) Step It Up – The Bamboos (Ubiquity) If you’re old enough or retro enough to recall the spirit and heart of old soul groups like Archie Bell and the Drells, these Aussies are channeling that same energy and nasty funk instrumentally. -

Jazz Festival Pr

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! DC Jazz Festival Neighborhood Venues Host More Than 80 Performances Citywide Jazz in the ‘Hoods, a major feature of the DC Jazz Festival, annually attracts a vibrant audience of thousands of music enthusiasts and highlights the city as a vibrant cultural capital by bringing jazz to all four quadrants of the nation’s capital, with over 80 performances at more than !40 neighborhood venues. View full schedule. !RAMW Member Jazz Festival Venues & Specials: Carmine’s DC 425 7th Street NW Washington, DC 20004 (202) 737-7770 http://www.carminesnyc.com !Special: Groups of 6 or more, show your ticket stub to receive a free desert. Bistrot Lepic & Wine Bar 1736 Wisconsin Ave NW Washington, DC 20007 (202) 333-0111 !http://www.bistrotlepic.com !June 10th & 15th- Jazz in the ‘Hoods Presents: Jazz in the Wine Room (7:00 pm) Acadiana 901 New York Ave NW Washington, DC 20001 (202) 408-8848 !http://www.acadianarestaurant.com/acadiana.html !June 14th - Jazz in the ‘Hoods Presents: Live Jazz Brunch (11:00 am) ! ! The Hamilton Live 600 14th St NW Washington, DC 20005 (202) 787-1000 !http://www.thehamiltondc.com June 10th - John Scofield ÜberJam Band featuring Andy Hess, Avi Bortnick & Tony !Mason: 7:30 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) June 11th - Paquito D’Rivera with Special Guest Edmar Castañeda: 7:30 pm (Doors !open at 6:30 pm) June 12th - The Bad plus Joshua Redman with Opener Underwater Ghost featuring !Allison Miller: 8:30 pm (Doors open at 7 pm) June 13th - (Early and Late Shows) Jack DeJohnette Trio featuring Ravi Coltrane & Matthew Garrison: 7:30 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) & 10:30 pm (Doors open at 9:30 !pm) June 14th - Stanton Moore Trio & Charlie Hunter Trio featuring Bobby Previte & Curtis !Fowlkes: 7:30 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) !June 15th - An Evening with Snarky Puppy (First Night): 8 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) June 16th - An Evening with Snarky Puppy (Second Night): 8 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm). -

School of Music

School of Music WIND ENSEMBLE AND CONCERT BAND Gerard Morris and Judson Scott, conductors WEDNESDAY, APRIL 12, 2017 | SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL | 7:30 P.M. PROGRAM Concert Band Judson Scott, conductor Rhythm Stand ....................................Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962) For Angels, Slow Ascending ......................... Greg Simon ’07 (b. 1985) The Green Hill ....................................Bert Appermont (b. 1973) Zane Kistner ‘17, euphonium Melodious Thunk ..............................David Biedenbender (b. 1984) INTERMISSION Wind Ensemble Gerard Morris, conductor Forever Summer (Premiere) ...................... Michael Markowski (b. 1986) Variations on Mein junges Leben hat ein End ................Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Ricker, trans. Music for Prague 1968 .............................. Karel Husa (1921–2016) I. Introduction and Fanfare II. Aria III. Interlude IV. Toccata and Chorale PROGRAM NOTES Concert Band notes complied by Judson Scott Wind Ensemble notes compiled by Gerard Morris Rhythm Stand (2004) ........................................... Higdon Rhythm Stand by Jennifer Higdon pays tribute to the constant presence of rhythm in our lives from the pulse of the world around us, celebrating the “regular order” we all experience, and incorporating traditional and nontraditional sounds within a 4/4-meter American-style swing. In the composer’s own words: “Since rhythm is everywhere, not just in music (ever listen to the lines of a car running across pavement, or a train on a railroad track?), I’ve incorporated sounds that come not from the instruments that you might find in a band, but from objects that sit nearby—music stands and pencils!” For Angels, Slow Ascending (2014) ................................. Simon The composer describes his inspiration and intention for the piece: In December 2013, we watched in silence and shock as a massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., claimed the lives of 27 people, including 20 young children.